Vol-XVI, West Bengal & Sikkim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panchayat Samity Medinipur 8 Pm Paschim Medinipur, Pin - 721121

List of Govt. Sponsored Libraries in the district of PASCHIM MEDINIPUR Name of the Workin Building Building Building Sl. Name of the Gram Panchayat / Block/ Panchayat Telephone No Type of Year of Year of Name Address District Librarian as on g Own or Kachha / Electrified No. Village / Ward No. Ward No. Samity/ Municipality (If any) Library Estab. Spon. 01.04.09 Hours Rented Pacca or Not At+ P.O. - Midnapore, District Library, Midnapore Paschim 03222 - Manas Kr. Sarkar, 1 pm - 1 Dist.: Paschim Medinipur, Pin - Ward No - 5 Ward No - 5 District 1956 1956 Own Pacca Electified Midnapur Municipality Medinipur 263403 In Charge 8 pm 721101 At + P.O. - Khirpai, Dist. - 12noo Halwasia Sub-Divisional Paschim 03225- Sub - 2 Paschim Medinipur, Ward No - 1 Ward No - 1 Khirpai Municipality Ajit Kr. Dolai 1958 1958 n - Own Pacca Electified Library Medinipur 260044 divisional Pin - 721232 7pm Vill - Kharida, P.O. - Kharagpur, Milan Mandir Town Kharagpur Paschim 1 pm - 3 Dist.: Paschim Medinipur, Pin - Ward No - 12 Ward No - 12 Tarapada Pandit Town 1944 1981 Own Pacca Electified Library Municipality Medinipur 8 pm 721301 At - Konnagar, P.O. - Ghatal,Dist.: Paschim 03225 - Debdas 11 am - 4 Ghatal Town Library Ward No - 15 Ward No - 15 Ghatal Municipality Town 1981 1981 Own Pacca Electified Paschim Medinipur, Pin - 721212 Medinipur 256345 Bhattacharya 6 pm Alapani Subdivisional At + P.O.- Jhargram, Dist.: Jhargram Paschim Rakhahari Kundu Sub - 1 pm - 5 Ward No - 14 Ward No - 14 1957 1962 Own Pacca Electified Library Paschim Medinipur, Pin 721507 Municipality Medinipur Lib. Asstt. divisional 8 pm Vill - Radhanagar, P.O. -

NAAC NBU SSR 2015 Vol II

ENLIGHTENMENT TO PERFECTION SELF-STUDY REPORT for submission to the National Assessment & Accreditation Council VOLUME II Departmental Profile (Faculty Council for PG Studies in Arts, Commerce & Law) DECEMBER 2015 UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL [www.nbu.ac.in] Raja Rammohunpur, Dist. Darjeeling TABLE OF CONTENTS Page number Departments 1. Bengali 1 2. Centre for Himalayan Studies 45 3. Commerce 59 4. Lifelong Learning & Extension 82 5. Economics 89 6. English 121 7. Hindi 132 8. History 137 9. Law 164 10. Library & Information Science 182 11. Management 192 12. Mass Communication 210 13. Nepali 218 14. Philosophy 226 15. Political Science 244 16. Sociology 256 Research & Study Centres 17. Himalayan Studies (Research Unit placed under CHS) 18. Women’s Studies 266 19. Studies in Local languages & Culture 275 20. Buddhist Studies (Placed under the Department of Philosophy) 21. Nehru Studies (Placed under the Department of Political Science) 22. Development Studies (Placed under the Department of Political Science) _____________________________________________________________________University of North Bengal 1. Name of the Department : Bengali 2. Year of establishment : 1965 3. Is the Department part of a School/Faculty of the University? Department is the Faculty of the University 4. Name of the programmes offered (UG, PG, M. Phil, Ph.D., Integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D.Sc., D.Litt., etc.) : (i) PG, (ii) M. Phil., (iii) Ph. D., (iv) D. Litt. 5. Interdisciplinary programmes and departments involved : NIL 6. Course in collaboration with other universities, industries, foreign institution, etc. : NIL 7. Details of programmes discontinued, if any, with reasons 2 Years M.Phil.Course (including Methadology in Syllabus) started in 2007 (Session -2007-09), it continued upto 2008 (Session - 2008-10); But it is discontinued from 2009 for UGC Instruction, 2009 regarding Ph. -

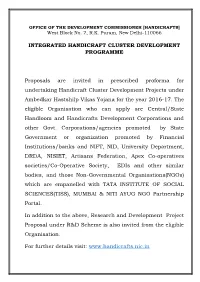

Integrated Handicraft Cluster Development Programme

OFFICE OF THE DEVELOPMENT COMMISSIONER [HANDICRAFTS] West Block No. 7, R.K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 INTEGRATED HANDICRAFT CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Proposals are invited in prescribed proforma for undertaking Handicraft Cluster Development Projects under Ambedkar Hastshilp Vikas Yojana for the year 2016-17. The eligible Organisation who can apply are Central/State Handloom and Handicrafts Development Corporations and other Govt. Corporations/agencies promoted by State Government or organization promoted by Financial Institutions/banks and NIFT, NID, University Department, DRDA, NISIET, Artisans Federation, Apex Co-operatives societies/Co-Operative Society, EDIs and other similar bodies, and those Non-Governmental Organisations(NGOs) which are empanelled with TATA INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES(TISS), MUMBAI & NITI AYUG NGO Partnership Portal. In addition to the above, Research and Development Project Proposal under R&D Scheme is also invited from the eligible Organisation. For further details visit: www.handicrafts.nic.in OFFICE OF THE DEVELOPMENT COMMISSIONER [HANDICRAFTS] West Block No. 7, R.K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 INTEGRATED HANDICRAFT CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Proposals are invited in prescribed proforma for undertaking Handicraft Cluster Development Projects under Ambedkar Hastshilp Vikas Yojana for the year 2015-16. The eligible Organisation who can apply are Central/State Handloom and Handicrafts Development Corporations and other Govt. Corporations/agencies promoted by State Government or organization promoted by Financial Institutions/banks and NIFT, NID, University Department, DRDA, NISIET, Artisans Federation, Apex Co-operatives societies/Co-Operative Society, EDIs and other similar bodies, and those Non- Governmental Organisations (NGOs) which are empanelled with TATA INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES (TISS), MUMBAI. The proposal can be submitted to Deputy Director (Cluster Cell), Hd. -

An Empirical Study on Tourists Interest Towards Archaeological Heritage Sites in West Bengal

International Journal of Research ISSN NO:2236-6124 An Empirical Study on Tourists interest towards Archaeological Heritage Sites in West Bengal Dr. Santinath Sarkar Assistant Professor, Dept. Of Education, University of Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal. Pincode: 741235 ABSTRACT: Tourism as a modern term is applicable to both international and domestic tourists. Tourism aims to recognize importance of it in generating local employment both directly in the tourism sector and in various support and resource management sectors. West Bengal has improved its share in international tourism receipts during the course of past decade i.e. from about 3.36% in 2005 to about 5.88% in 2016 of foreign tourists visiting India. Archaeological heritage is a vital part of the tourism product and is one of the energetic factors that can develop the competitiveness of a tourism destination. Archaeological heritage tourism is one of the largest and fastest growing global tourism markets and it covers all aspects of travel that provide an opportunity for visitors to learn about other areas’ history, culture and life style. The present investigated the relationship between tourists’ satisfaction and the attributes of archaeological heritage destinations in West Bengal (WB). The area of the study at selected archaeological heritage destinations of West Bengal, which is located in eastern India and the data of this study have been collected from the on-site survey method at Victoria Memorial Hall, Belur Math, Chandannagar, Hazarduari, Shantiniketan, Bishnupur. These destinations are highly of the rich archaeological heritage of the State of West Bengal. The sample population for this study was composed of tourists who visited in these places in between December 2016 to January 2017. -

Annexure-VI-Eng Purba Bardhaman Corrected Final Final.Xlsx

Annexure-6 (Chapter 2, para 2.9.1) LIST OF POLLING STATIONS For 260-Bardhaman Dakshin Assembly Constituency within 39-Bardhaman-Durgapur Perliamentry Constitutency Wheather Sr. No. for all voters of the Building in which will be Locality Polling Area or men only Polling located or women Station only 1 2 3 4 5 Kamal Sayar, Ward no. 26, Burdwan Municipality University Engineering 1. Both side of Kamal Sayar, 2. East Side of 1 For all voters Sadar Burdwan, Pin-713104. College, Kamal Sayar Research Hostel road Goda, Ward No. 26, Burdwan Municipality Sadar Goda Municipal F.P. School (R- 1.Goda Kajir Hat, 2. Goda Sib tala, 3. 2 For all voters Burdwan, Pin-713102. 1) Tarabag, 4. Golapbag Goda, Ward No. 26, Burdwan Municipality Sadar Goda Municipal F.P. School (R- 1. Goda Koit tala, 2. Goda Kumirgorh, 3. 3 For all voters Burdwan, Pin-713102. 2) Goda Jhumkotala, 4. Goda Khondekar para, 1. Banepukur Dakshinpar, 2. Banepukur Goda, Ward No. 26, Burdwan Municipality Sadar pashimpar, 3. Das para, 4. Simultala, 5. 4 Goda F.P. School (R-1) For all voters Burdwan, Pin-713102. Banepukur purba para, 6. Goda Roy colony, 7. Goda Majher para, 8. Goda Dangapara. 1. Goda Mondal Para, 2. Goda Molla Para, Goda, Ward No. 26, Burdwan Municipality Sadar 5 Goda F.P. School (R-2) 3.Dafadar Para, 4. Goda Bhand para, 5. Goda For all voters Burdwan, Pin-713102. Bizili par, 6. Nuiner Par 1. Goda math colony, 2. Goda kaibartya para, 3. Goda sibtala, 4. Goda mali para, 5. Goda Goda, Ward No. -

SANDESH India Association of Nebraska December 2014 2531 Shamrock Road Volume 1 Issue 12 Omaha NE 68154

SANDESH India Association of Nebraska December 2014 2531 Shamrock Road Volume 1 Issue 12 Omaha NE 68154 This is our twelfth and final edition of Sandesh (the e-newsletter for IAN) for the year 2014. The publication committee is proud to have published a new edition of Sandesh every month this year. All the published editions can be found at http://www.indiaassociationofnebraska.org/Sandesh.aspx Every edition of Sandesh was comprised of three parts – an editorial, a highlight and a spotlight. The editorial featured messages from various committee chairpersons and it provided some information about the committees’ that comprise IAN and their function. In the highlight section, one event organized by IAN that month was featured and we aimed to provide a glimpse into the event. In the spotlight section we also worked on presenting the State series, which was aimed at being informational and provided some little known facts about many of the Indian states. This final edition contains a quick recap of the events in the year gone by and the operating budget for 2014. On behalf of all of us at the editorial desk, we would like to extend our deepest thanks to all the committee chairpersons, who took time out of their busy schedules to put together editorials for each month. We would also like to thank the president Mr. Joseph Selvaraj for his constant support and availability to help. President’s Message: Dear Friends, Namaste! It is hard to believe that our team has completed the yearly term and contributed their best to the community. -

Jadupatias in the Aesthetics of the Craft of Jewellery

Jadupatias in the Aesthetics of the Craft of Jewellery Long Abstract The Jadupatias is an obscure community in Jharkhand, India, who engage in the dokra jewellery making. The aesthetics of brass jewellery are not just based on the aspect of ‘charm’. But there is a larger social construction of its aesthetics of making. It is based on their own environment, the materials they procure from their environment and other secular and non- secular agencies. Family, religion, markets (both local and global) and intervention from the government and non government agencies construct the aesthetic of production, and in turn this constitute their larger social world of interaction which involves and includes the petty businessmen to whom they sell their products, the customers and the artists and the designers with whom they come in contact while in training camp. But, it’s sad that they have forgotten their own stories and songs that constituted the aesthetic of jewellery making earlier, as it has been largely replaced by the songs and stories on the transistors that play in the background. The issue is not that whether the folk songs or stories can always make a claim for their moralistic and superior status over the products of culture industries. But, what was part of their production will never be told or reproduced. Thus the paper would address the role of these agencies that construct the aesthetics of craft which have multiple relationships with art. Also, it would delineate how the community attitude changes towards various agencies which construct the aesthetics of making and their larger social world. -

Arts-Integrated Learning

ARTS-INTEGRATED LEARNING THE FUTURE OF CREATIVE AND JOYFUL PEDAGOGY The NCF 2005 states, ”Aesthetic sensibility and experience being the prime sites of the growing child’s creativity, we must bring the arts squarely into the domain of the curricular, infusing them in all areas of learning while giving them an identity of their own at relevant stages. If we are to retain our unique cultural identity in all its diversity and richness, we need to integrate art education in the formal schooling of our students for helping them to apply art-based enquiry, investigation and exploration, critical thinking and creativity for a deeper understanding of the concepts/topics. This integration broadens the mind of the student and enables her / him to see the multi- disciplinary links between subjects/topics/real life. Art Education will continue to be an integral part of the curriculum, as a co-scholastic area and shall be mandatory for Classes I to X. Please find attached the rich cultural heritage of India and its cultural diversity in a tabular form for reading purpose. The young generation need to be aware of this aspect of our country which will enable them to participate in Heritage Quiz under the aegis of CBSE. TRADITIONAL TRADITIONAL DANCES FAIRS & FESTIVALS ART FORMS STATES & UTS DRESS FOOD (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) Kuchipudi, Burrakatha, Tirupati Veerannatyam, Brahmotsavam, Dhoti and kurta Kalamkari painting, Pootha Remus Andhra Butlabommalu, Lumbini Maha Saree, Langa Nirmal Paintings, Gongura Pradesh Dappu, Tappet Gullu, Shivratri, Makar Voni, petticoat, Cherial Pachadi Lambadi, Banalu, Sankranti, Pongal, Lambadies Dhimsa, Kolattam Ugadi Skullcap, which is decorated with Weaving, carpet War dances of laces and fringes. -

District Survey Report, Purulia District, West Bengal 85

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT (For mining of minor minerals) As per Notification No. S.O.3611 (E) New Delhi dated 25TH Of July 2018 Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) PREPARED BY: RSP GREEN DEVELOPMENT AND LABORATORIES PVT. LTD. ISO 9001:2015 & ISO 14001:2015 Certified Company QCI-NABET ACCREDITED CONSULTANT JANUARY, 2021 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT DISTRICT SURVEY DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT, JHARGRAM DISTRICT, WEST BENGAL CONTENTS SL. TOPIC DETAILS PAGE NO. NO CONTENT I - II ABBREVIATIONS USED III - IV LIST OF TABLES V - VI LIST OF MAPS VII LIST OF ANNEXURES VIII CONFIDENTIALITY CLAUSE IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENT X FIELD PHOTOGRAPHS XXX 1 PREFACE 1 2 INTRODUCTION 2 3 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE DISTRICT 4 - 16 a. General information 3 b. Demography 3 - 7 c. Climate condition 7 d. Rain fall (month wise) and humidity 8 e. Topography and terrain 8 - 9 f. Water course and hydrology 9 - 10 g. Ground water development 10 - 13 h. Drainage system (general) 13 i. Cropping pattern 13 - 15 j. Landform and seismicity 15 k. Flora 15 - 16 l. Fauna 16 4 PHYSIOGRAPHY OF THE DISTRICT 17 - 22 o General landform 17 o Soil 17 - 19 o Rock pattern 19 - 20 o Different geomorphological units 20 o Drainage basins 21 - 22 5 LAND USE PATTERN OF THE DISTRICT 23 - 30 . Introduction 23 - 26 a. Forest 26 - 27 b. Agriculture & Irrigation 27 - 29 c. Horticulture 29 d. Mining 30 6 GEOLOGY 31 - 34 Regional geology 31 - 33 Local geology 33 - 34 7 MINERAL WEALTH 35 - 37 Overview of the mineral 35 - 37 resources (covering all minerals) I PREPARED BY: RSP GREEN DEVELOPMENT AND LABORATORIES PVT. -

New Concept Calendar

From the innocuous marigold to the conch shell, from the deep sea to the bees, the birds and their complex abodes, to the intricacies of the human body, to the incredible geometry of the solar system, all things big and small in this universe reveal superlative design. Bhubaneswar Office D-60, 1st Floor Injecting the rhythm, the balance and harmony displayed Phase-I, Maitri Vihar in nature into the human environment remains the quest Bhubaneswar - 751023 as well as the challenge of this millennium. Tel: 0674 - 2301299 email: [email protected] With 25 years of collective experience in transformational research and communication, we at New Concept are Chennai Office CALENDAR geared to meet this challenge head on! Old No-65/2, New No-149 LUZ Church Road New Concept specialises in: Mylapore, Chennai – 600004 2013 l Rigorous quantitative, qualitative and evidence-based Tel: 044 - 24984402 research; email: [email protected] l Analytical documentation of processes and outcomes; Delhi Office l Supportive monitoring & evaluation, impact 206, 2nd Floor, LSC assessments; Pocket D & E Market l Web-based monitoring systems, content Sarita Vihar, New Delhi – 110076 management, resource centres, repositories; Tel: 011 - 64784300 Fax: 011 - 26972743 email: [email protected] l Researching into knowledge, attitude and behaviours of communities; Hyderabad Office l Developing effective communication strategies for “Vani Nilayam” H.No. 6-3-903/A/4/1 behaviour change; 2nd Floor, Surya Nagar Colony Somajiguda, Hyderabad – 500082 l Capacity building for grassroot, frontline, managerial Tel: 040 - 23414986 functionaries and stakeholders; and email: [email protected] l Producing artistic communication materials that mobilise communities. -

Brochure Handicrafts

INDIAN HANDICRAFTS From India to the world, It’s Handmade with Love. www.reyatrade.com DHOKRA Dhokra (also spelt Dokra) is non–ferrous metal casting using the lost wax technique. This sort of metal casting has been used in India for over 4,000 years and is still used. One of the earliest known lost wax artefacts is the dancing girl of Mohenjo-daro. The product of dhokra artisans are in great demand in domestic and foreign markets because of primitive simplicity, enchanting folk motifs and forceful form. Dhokra horses, elephants, peacocks, owls, religious images, measuring bowls, and lamp caskets etc., are highly appreciated. Reyatrade TERRACOTTA The word ‘terracotta’ has been derived from the Latin phrase “terra cocta”, which means ‘baked earth’. Terracotta can be simple defined as clay based earthenware. It is something that we see everywhere. From the roadside tea shop to the flower pots in our balconies, it is part of our daily lives. Reyatrade LEATHER ART Leather puppets and Lamp shades are the authentic product of Andhra Pradesh art and crafts. The motifs and designs are mostly inspired from the hindu epics such as, Ramayana and Mahabharata. The colors which are derived from vegetables dyes, like brilliant red, green, white, yellow, browns and orange are popular. Creating small holes inside the decorative patterns enhances the attraction of the lampshade, which is done using a pogaru (chisel). Reyatrade PATTACHITRA Pattachitra or Patachitra is a general term for traditional, cloth-based scroll painting, based in the eastern Indian states of Odisha and West Bengal. Pattachitra art form is known for its intricate details as well as mythological narratives and folktales inscribed in it. -

Call for Expressions of Interest for Final Evaluation of the Project

Call for expressions of interest for Final Evaluation of the project “Development of Rural Craft and Cultural Hubs in West Bengal to support inter-generational transmission of rural craft and performing arts”, funded by the Department of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises and Textiles (MSME&T), Government of West Bengal, and implemented in partnership with UNESCO New Delhi and Contact Base. UNESCO New Delhi Cluster Office for Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Maldives, and Sri Lanka is seeking expressions of interest from qualified and experienced individuals, to conduct the final evaluation of the project titled “Development of Rural Craft and Cultural Hubs in West Bengal to support inter-generational transmission of rural craft and performing arts”. 1. PROJECT BACKGROUND Context While West Bengal is rich in performing arts and crafts, the continuity of such traditions is at stake due to the low socio-economic status of the practitioners in general that does not encourage the younger generation to pursue the practices. The reduced opportunities for practice has also led to the deterioration in the quality of knowledge and skills of the practitioners. Absence of public exposure has not allowed them to tap into opportunities in the contemporary context. In light of the above, UNESCO and the Department of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises and Textiles (MSME&T), Government of West Bengal, signed a Funds-in-Trust (FiT) Agreement for a duration of 30 months in August 2016 to promote community well-being through the safeguarding of performing arts and crafts in West Bengal. The project called Rural Craft and Cultural Hubs (RCCH) is being implemented by UNESCO in partnership with Contact Base (also called Banglanatak), a NGO based in Kolkata.