A Way Forward for Positive Migration Governance in Libya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Oil Exports on Economic Growth – the Case of Libya

Czech University of Life Sciences Prague Faculty of Economics and Management Department of Economics The Impact of oil Exports on Economic Growth – The Case of Libya Doctoral Thesis Author: Mousbah Ahmouda Supervisor: Doc. Ing. Luboš Smutka, Ph.D. 2014 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to evaluate and measure the relationship between oil exports and economic growth in Libya by using advancement model and utilize Koyck disseminated lag regression technique (Koyck, 1954; Zvi, 1967) to check the relationship between the oil export of Libya and Libyan GDP using annual data over the period of 1980 to 2013. The research focuses on the impacts of oil exports on the economic growth of Libya. Being a developing country, Libya’s GDP is mainly financed by oil rents and export of hydrocarbons. In addition, the research are applied to test the hypothesis of economic growth strategy led by exports. The research is based on the following hypotheses for testing the causality and co- integration between GDP and oil export in Libya as to whether there is bi-directional causality between GDP growth and export, or whether there is unidirectional causality between the two variables or whether there is no causality between GDP and oil export in Libya. Importantly, this research aims at studying the impact of oil export on the economy. Therefore, the relationship of oil export and economic growth for Libya is a major point. Also the research tried to find out the extent and importance of oil exports on the trade, investment, financing of the budget and the government expenditure. -

Download File

Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 Eileen Ryan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Eileen Ryan All rights reserved ABSTRACT Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 By Eileen Ryan In the first decade of their occupation of the former Ottoman territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in current-day Libya, the Italian colonial administration established a system of indirect rule in the Cyrenaican town of Ajedabiya under the leadership of Idris al-Sanusi, a leading member of the Sufi order of the Sanusiyya and later the first monarch of the independent Kingdom of Libya after the Second World War. Post-colonial historiography of modern Libya depicted the Sanusiyya as nationalist leaders of an anti-colonial rebellion as a source of legitimacy for the Sanusi monarchy. Since Qaddafi’s revolutionary coup in 1969, the Sanusiyya all but disappeared from Libyan historiography as a generation of scholars, eager to fill in the gaps left by the previous myopic focus on Sanusi elites, looked for alternative narratives of resistance to the Italian occupation and alternative origins for the Libyan nation in its colonial and pre-colonial past. Their work contributed to a wider variety of perspectives in our understanding of Libya’s modern history, but the persistent focus on histories of resistance to the Italian occupation has missed an opportunity to explore the ways in which the Italian colonial framework shaped the development of a religious and political authority in Cyrenaica with lasting implications for the Libyan nation. -

Medical Conditions in the Western Desert and Tobruk

CHAPTER 1 1 MEDICAL CONDITIONS IN THE WESTERN DESERT AND TOBRU K ON S I D E R A T I O N of the medical and surgical conditions encountered C by Australian forces in the campaign of 1940-1941 in the Wester n Desert and during the siege of Tobruk embraces the various diseases me t and the nature of surgical work performed . In addition it must includ e some assessment of the general health of the men, which does not mean merely the absence of demonstrable disease . Matters relating to organisa- tion are more appropriately dealt with in a later chapter in which the lessons of the experiences in the Middle East are examined . As told in Chapter 7, the forward surgical work was done in a main dressing statio n during the battles of Bardia and Tobruk . It is admitted that a serious difficulty of this arrangement was that men had to be held for some tim e in the M.D.S., which put a brake on the movements of the field ambulance , especially as only the most severely wounded men were operated on i n the M.D.S. as a rule, the others being sent to a casualty clearing statio n at least 150 miles away . Dispersal of the tents multiplied the work of the staff considerably. SURGICAL CONDITIONS IN THE DESER T Though battle casualties were not numerous, the value of being able to deal with varied types of wounds was apparent . In the Bardia and Tobruk actions abdominal wounds were few. Major J. -

Africa 1952-1953

SUMMARY OF RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS IN AFRICA 1952-53 Supplement to World Economic Report UNITED NATIONS UMMARY OF C T ECONOMIC EVE OPME TS IN AF ICA 1952-53 Supplement World Economic Report UNITED NATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS New York, 1954 E/2582 ST/ECA/26 May 1954 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sal es No.: 1951\..11. C. 3 Price: $U.S. $0.80; 6/- stg.; Sw.fr. 3.00 (or equivalent in other currencies) FOREWDRD This report is issued as a supplement to the World Economic Report, 1952-53, and has been prepared in response to resolution 367 B (XIII) of the Economic and Social Council. It presents a brief analysis of economic trends in Africa, not including Egypt but including the outlying islands in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, on the basis of currently available statistics of trade, production and development plans covering mainly the year 1952 and the first half of 1953, Thus it carries forward the periodic surveys presented in previous years in accordance with resolution 266 (X) and 367 B (XIII), the most recent being lIRecent trends in trade, production and economic development plansll appearing as part II of lIAspects of Economic Development in Africall issued in April 1953 as a supplement to the World Economic Report, 1951-52, The present report, like the previous ones, was prepared in the Division of Economic Stability and Development of the United Nations Department of Economic Affairs. EXPLANATION OF SYMBOLS The following symbols have been used in the tables throughout the report: Three dots ( ... ) indicate that data -

WESTERN DESERT CAMPAIGN Sept-Nov1940 Begin Between the 10Th and 15Th October and to Be Concluded by Th E End of the Month

CHAPTER 7 WESTERN DESERT CAMPAIG N HEN, during the Anglo-Egyptian treaty negotiations in 1929, M r W Bruce as Prime Minister of Australia emphasised that no treat y would be acceptable to the Commonwealth unless it adequately safeguarded the Suez Canal, he expressed that realisation of the significance of sea communications which informed Australian thoughts on defence . That significance lay in the fact that all oceans are but connected parts o f a world sea on which effective action by allies against a common enem y could only be achieved by a common strategy . It was as a result of a common strategy that in 1940 Australia ' s local naval defence was denude d to reinforce offensive strength at a more vital point, the Suez Canal an d its approaches. l No such common strategy existed between the Germans and the Italians, nor even between the respective dictators and thei r commanders-in-chief . Instead of regarding the sea as one and indivisible , the Italians insisted that the Mediterranean was exclusively an Italia n sphere, a conception which was at first endorsed by Hitler . The shelvin g of the plans for the invasion of England in the autumn of 1940 turne d Hitler' s thoughts to the complete subjugation of Europe as a preliminary to England ' s defeat. He became obsessed with the necessity to attack and conquer Russia . In viewing the Mediterranean in relation to German action he looked mainly to the west, to the entry of Spain into the war and th e capture of Gibraltar as part of the European defence plan . -

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1. Detailed Methodology 2. Participation 3. Awareness 4. Knowledge 5. Communication 6. Service Delivery 7. Legitimacy 8. Drivers of Legitimacy 9. Focus Group Recommendations 10. Demographics Detailed Methodology • The survey was conducted on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research by Altai Consulting. This research is intended to support the development and evaluation of IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative programming with municipal councils. The research consisted of quantitative and qualitative components, conducted by IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative respectively. • Data was collected April 14 to May 24, 2016, and was conducted over the phone from Altai’s call center using computer-assisted telephone technology. • The sample was 2,671 Libyans aged 18 and over. • Quantitative: Libyans from the 22 administrative districts were interviewed on a 45-question questionnaire on municipal councils. In addition, 13 municipalities were oversampled to provide a more focused analysis on municipalities targeted by programming. Oversampled municipalities include: Tripoli Center (224), Souq al Jumaa (229), Tajoura (232), Abu Salim (232), Misrata (157), Sabratha (153), Benghazi (150), Bayda (101), Sabha (152), Ubari (102), Weddan (101), Gharyan (100) and Shahat (103). • The sample was post-weighted in order to ensure that each district corresponds to the latest population pyramid available on Libya (US Census Bureau Data, updated 2016) in order for the sample to be nationally representative. • Qualitative: 18 focus groups were conducted with 5-10 people of mixed employment status and level of education in Tripoli Center (men and women), Souq al Jumaa (men and women), Tajoura (men), Abu Salim (men), Misrata (men and women), Sabratha (men and women), Benghazi (men and women), Bayda (men), Sabha (men and women), Ubari (men), and Shahat (men). -

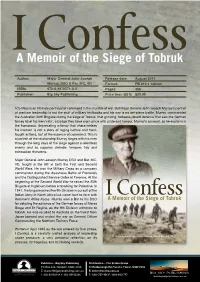

A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk

I Confess A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk Author: Major General John Joseph Release date: August 2011 Murray, DSO & Bar, MC, VD Format: PB 210 x 148mm ISBN: 978-0-9870574-8-8 Pages: 256 Publisher: Big Sky Publishing Price (incl. GST): $29.99 I Confess is an intimate portrayal of command in the crucible of war. But Major General John Joseph Murray’s portrait of wartime leadership is not the stuff of military textbooks and his war is no set-piece battle. Murray commanded the Australian 20th Brigade during the siege of Tobruk, that grinding, tortuous desert defence that saw the German forces label his men ‘rats’, a badge they have worn since with pride and honour. Murray’s account, as he explains in the humorous, deprecating whimsy that characterises his memoir, is not a story of raging battles and hard- fought actions, but of the essence of command. This is a portrait of the relationship Murray forges with his men through the long days of the siege against a relentless enemy and as supplies dwindle, tempers fray and exhaustion threatens. Major General John Joseph Murray DSO and Bar, MC, VD, fought in the AIF in both the First and Second World Wars. He won the Military Cross as a company commander during the disastrous Battle of Fromelles and the Distinguished Service Order at Peronne. At the beginning of the Second World War he raised the 20th Brigade at Ingleburn before embarking for Palestine. In 1941, the brigade joined the 9th Division in pursuit of the Italian Army in North Africa but came face to face with Rommel’s Afrika Korps. -

LONCHENA-THESIS-2020.Pdf

FAILED STATES: DEFINING WHAT A FAILED STATES IS AND WHY NOT ALL FAILED STATES AFFECT UNITED STATES NATIONAL SECURITY by Timothy Andrew Lonchena A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Global Security Studies Baltimore, Maryland May 2020 2020 Timothy Lonchena All rights reserved Abstract: Failed States have been discussed for over the past twenty years since the terrorist attacks of the United States on September 11th, 2001. The American public became even more familiar with the term “failed states” during the Arab Spring movement when several countries in the Middle East and North Africa underwent regime changes. The result of these regime changes was a more violent group of terrorists, such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). This thesis will address how to define failed states to ensure there is an understood baseline when looking to determine if a state could possibly fail. Further, this thesis will examine the on-going debate addressing the question of those who claim failed states can’t be predicted and determine if analytic modeling can be applied to the identification of failed states. The thesis also examines the need to identify “failed states” before they fail and will also discuss the effects certain failed states have directly on United States national security. Given this, the last portion of this paper and argument to be addressed will determine if there are certain failing states that the United States will not provide assistance to, as it is not in the best interest of our national security and that of our allies. -

After Gaddafi 01 0 0.Pdf

Benghazi in an individual capacity and the group it- ures such as Zahi Mogherbi and Amal al-Obeidi. They self does not seem to be reforming. Al-Qaeda in the found an echo in the administrative elites, which, al- Islamic Maghreb has also been cited as a potential though they may have served the regime for years, spoiler in Libya. In fact, an early attempt to infiltrate did not necessarily accept its values or projects. Both the country was foiled and since then the group has groups represent an essential resource for the future, been taking arms and weapons out of Libya instead. and will certainly take part in a future government. It is unlikely to play any role at all. Scenarios for the future The position of the Union of Free Officers is unknown and, although they may form a pressure group, their membership is elderly and many of them – such as the Three scenarios have been proposed for Libya in the rijal al-khima (‘the men of the tent’ – Colonel Gaddafi’s future: (1) the Gaddafi regime is restored to power; closest confidants) – too compromised by their as- (2) Libya becomes a failing state; and (3) some kind sociation with the Gaddafi regime. The exiled groups of pluralistic government emerges in a reunified state. will undoubtedly seek roles in any new regime but The possibility that Libya remains, as at present, a they suffer from the fact that they have been abroad divided state between East and West has been ex- for up to thirty years or more. -

Libya Conflict Insight | Feb 2018 | Vol

ABOUT THE REPORT The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and Libya Conflict recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision making and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. Insight CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Mr. Hervé Wendyam Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff Situation analysis EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Libya achieved independence from United Nations (UN) trusteeship in 1951 Michelle Mendi Muita (Editor) as an amalgamation of three former Ottoman provinces, Tripolitania, Mikias Yitbarek (Design & Layout) Cyrenaica and Fezzan under the rule of King Mohammed Idris. In 1969, King Idris was deposed in a coup staged by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. He promptly abolished the monarchy, revoked the constitution, and © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, established the Libya Arab Republic. By 1977, the Republic was transformed Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. into the leftist-leaning Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. In the 1970s and 1980s, Libya pursued a “deviant foreign policy”, epitomized February 2018 | Vol. 1 by its radical belligerence towards the West and its endorsement of anti- imperialism. In the late 1990s, Libya began to re-normalize its relations with the West, a development that gradually led to its rehabilitation from the CONTENTS status of a pariah, or a “rogue state.” As part of its rapprochement with the Situation analysis 1 West, Libya abandoned its nuclear weapons programme in 2003, resulting Causes of the conflict 2 in the lifting of UN sanctions. -

A Struggle for Every Single Boat

A Struggle for Every Single Boat Alarm Phone: Central Mediterranean Analysis, July - December 2020 ‘Mother’ I do not like death as you think, I just have no desire for life… I am tired of the situation I am in now.. If I did not move then I will die a slow death worse than the deaths in the Mediterranean. ‘Mother’ The water is so salty that I am tasting it, mom, I am about to drown. My mother, the water is very hot and she started to eat my skin… Please mom, I did not choose this path myself… the circumstances forced me to go. This adventure, which will strip my soul, after a while… I did not find myself nor the one who called it a home that dwells in me. ‘Mother’ There are bodies around me, and others hasten to die like me, although we know whatever we do we will die.. my mother, there are rescue ships! They laugh and enjoy our death and only photograph us when we are drowning and save a fraction of us… Mom, I am among those who will let him savor the torment and then die. Whatever bushes and valleys of my country, my neighbours’ daughters and my cousins, my friends with whom I play football and sing with them in the corners of homes, I am about to leave everything related to you. Send peace to my sweetheart and tell her that she has no objection to marrying someone other than me… If I ask you, my sweetheart, tell her that this person whom we are talking about, he has rested. -

For Ubari LBY2007 Libya

Research Terms of Reference Area-Based Assessment (ABA) for Ubari LBY2007 Libya 22nd of January, 2021 V3 1. Executive Summary Country of intervention Libya Type of Emergency □ Natural disaster X Conflict Type of Crisis □ Sudden onset □ Slow onset X Protracted Mandating Body/ EUTF Agency Project Code 14EHG Overall Research Timeframe (from 01/10/2020 to 14/04/2021 research design to final outputs / M&E) Research Timeframe 1. Start collect data: 26/01/2021 5. Preliminary presentation: 13/03/2021 Add planned deadlines 2. Data collected: 25/02/2021 6. Outputs sent for validation: 31/03/2021 (for first cycle if more 3. Data analysed: 05/03/2021 7. Outputs published: 14/04/2021 than 1) 4. Data sent for validation: 31/03/2021 8. Final presentation: 14/04/2021 Number of X Single assessment (one cycle) assessments □ Multi assessment (more than one cycle) [Describe here the frequency of the cycle] Humanitarian Milestone Deadline milestones □ Donor plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ Specify what will the □ Inter-cluster plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ assessment inform and □ Cluster plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ when e.g. The shelter cluster □ NGO platform plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ will use this data to X Other (Specify): 31/03/2021 The Area-Based Assessment draft its Revised Flash (ABA) for Ubari will directly inform ACTED Appeal; protection activities in Ubari. (See rationale) Audience Type & Audience type Dissemination Dissemination Specify X Strategic X General Product Mailing (e.g.