31| Camel Expeditions Michael Asher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africa's Role in Nation-Building: an Examination of African-Led Peace

AFRICA’S ROLE IN NATION-BUILDING An Examination of African-Led Peace Operations James Dobbins, James Pumzile Machakaire, Andrew Radin, Stephanie Pezard, Jonathan S. Blake, Laura Bosco, Nathan Chandler, Wandile Langa, Charles Nyuykonge, Kitenge Fabrice Tunda C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2978 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0264-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: U.S. Air Force photo/ Staff Sgt. Ryan Crane; Feisal Omar/REUTERS. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since the turn of the century, the African Union (AU) and subregional organizations in Africa have taken on increasing responsibilities for peace operations throughout that continent. -

Pastoralist Voices-April09-Final

Pastoralist Voices May 2009 Volume 1 , Issue 15 Photos: OCHA For a Policy Framework on Pastoralism in Africa African Union and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Pastoralists across Africa have called for a continent-wide policy framework that will begin to secure and protect the lives, livelihood and rights of pastoralists across Africa. The African Union has responded to this call and has begun formulating a Pastoral Policy Framework for the Continent. Pastoralist Voices is a monthly bulletin that supports this process by promoting the voices and perspectives of pastoralists, and facilitating information flow between the major stakeholders in the policy process including pastoralists, the African Union, Regional Economic Communities and international agencies. To subscribe to Pastoralist Voices please write to: [email protected] In this issue Marginalization of Pastoralists in the Dar- Marginalization of pastoralists in the Darfur conflict in fur conflict in Northern Sudan Northern Sudan P g 1, 2, 3 and 4 Why Humanitarian interventions are failing to address Lack of support to pastoralists’ security needs in Central and food crisis in pastoral areas pg 1, 4 and 5 East Africa have implications for national and regional security. Making disarmament work in pastoral areas of Southern The conflict in Northern Sudan is being attributed to a large Sudan P g 6 extent to pastoralists’ marginalization in the region. A detailed report by Tuft University’s Feinstein Interna- tional Center is urging Humanitarian actors to take account of Why humanitarian interventions the particular vulnerability of pastoral groups, and to recognize are failing to address food crisis that their needs are qualitatively different from those of IDPs in in Pastoral Areas the region. -

Arabian Sands Ebook

ARABIAN SANDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Wilfred Thesiger,Rory Stewart | 368 pages | 22 Jun 2011 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141442075 | English | London, United Kingdom Arabian Sands PDF Book I had found satisfaction in the stimulating harshness of this empty land, pleasure in the nomadic life which I had led. Read it Forward Read it first. Last, but not least, Thesiger is a good photographer, working well with black and white film to capture the desert landscape, the pure-bred camels, the faces of the tribesmen and the cities on the coast. The very slowness of our march diminished its monotony. Sometimes I counted my footsteps to a bush or to some other mark, and this number seemed but a trifle deducted from the sum that lay ahead of us. He learned their language, cared for them, and tried to understand their world. We then halted and, using the loads and camelsaddles, quickly built a small perimeter round our camp, which was protected on one side by the river. I read this book on a beach somewhere far away from the deserts of Arabia. It had been wildly exciting to charge with a mob of mounted tribesmen through thick bush after a galloping lion, to ride close behind it when it tired, while the Arabs waved their spears and shouted defiance, to circle round the patch of jungle in which it had come to bay, trying to make out its shape among the shadows, while the air quivered with its growls. Penguin Classics. When I say everything I really mean that, there's nothing that he is too embarrassed to discuss about camels or the Bedu for that matter. -

A Barren Legacy? the Arabian Desert As Trope in English Travel Writing, Post-Thesiger

A Barren Legacy? The Arabian Desert as Trope in English Travel Writing, Post-Thesiger Jenny Owen A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2020 Note on Copyright This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed to the owner of the Intellectual Property Rights. Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... 4 Introduction: Arabia, the Land of Legend ................................................................ 5 Locating Arabia ................................................................................................... 11 Studying Arabia as a country of the mind ............................................................. 18 The Lawrence and Thesiger legacy ...................................................................... 22 Mapping the thesis: an outline of the chapters ...................................................... 27 1. In Literary Footsteps: The Prevalence of -

Reference Code

THESIGER GB165-0545 Reference code: GB165-0545 Title: Sir Wilfred Thesiger Collection Name of creator: Thesiger, Sir Wilfred Patrick (1910-2003), Knight, Diplomat, Author and Traveller Dates of creation of material: c1954 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 27 magic lantern slides Biographical history: Thesiger, Sir Wilfred Patrick (1910-2003), Knight, Diplomat, Author and Traveller. Born 3 June 1910, son of Captain Wilfred Gilbert Thesiger and Kathleen Mary. Educated at Eton College and Magdalen College, Oxford University. Received a grant from the Royal Geographical Society in 1935 to explore the Aussa Sultanate and the country of Abyssinia between 1933-1934. Joined the Sudan Political Service and served in desert campaigns between 1935-1940. Joined the North and East African Campaign with rank of Major during World War II. Worked in Arabia with the Desert Locusts Research Organization between 1945-1949. Explored the Empty Quarter (desert of southern Arabia) between 1946-1950. From 1950 onwards, explored French West Africa, Iraq, Kurdistan, Pakistan, Persia and Kenya. Lived with Marsh Arabs in southern Iraq over seven years from 1950 to the Iraqi Revolution. Returned to England in 1994. Died 24 August 2003. Scope and content: 27 magic lantern slides of the Marsh Arabs in southern Iraq, c1954. The slides depict ethnological scenes of the Marsh Arabs’ communal life such as fishing, hunting, communal gatherings, landscape panoramic views and portraits. All of the slides are labelled ‘Royal Central Asian Society’ and the original packaging was labelled ‘?1954. Marsh Arabs W. Thesiger’. Access conditions: Open Language of material: English Conditions governing reproduction: There are no special restrictions on copying other than statutory regulations (UK Copyright law). -

Lonely Planet Publications 150 Linden St, Oakland, California 94607 USA Telephone: 510-893-8556; Facsimile: 510-893-8563; Web

Lonely Planet Publications 150 Linden St, Oakland, California 94607 USA Telephone: 510-893-8556; Facsimile: 510-893-8563; Web: www.lonelyplanet.com ‘READ’ list from THE TRAVEL BOOK by country: Afghanistan Robert Byron’s The Road to Oxiana or Eric Newby’s A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush, both all-time travel classics; Idris Shah’s Afghan Caravan – a compendium of spellbinding Afghan tales, full of heroism, adventure and wisdom Albania Broken April by Albania’s best-known contemporary writer, Ismail Kadare, which deals with the blood vendettas of the northern highlands before the 1939 Italian invasion. Biografi by Lloyd Jones is a fanciful story set in the immediate post-communist era, involving the search for Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha’s alleged double Algeria Between Sea and Sahara: An Algerian Journal by Eugene Fromentin, Blake Robinson and Valeria Crlando, a mix of travel writing and history; or Nedjma by the Algerian writer Kateb Yacine, an autobiographical account of childhood, love and Algerian history Andorra Andorra by Peter Cameron, a darkly comic novel set in a fictitious Andorran mountain town. Approach to the History of Andorra by Lídia Armengol Vila is a solid work published by the Institut d’Estudis Andorrans. Angola Angola Beloved by T Ernest Wilson, the story of a pioneering Christian missionary’s struggle to bring the gospel to an Angola steeped in witchcraft Anguilla Green Cane and Juicy Flotsam: Short Stories by Caribbean Women, or check out the island’s history in Donald E Westlake’s Under an English Heaven Antarctica Ernest Shackleton’s Aurora Australis, the only book ever published in Antarctica, and a personal account of Shackleton’s 1907-09 Nimrod expedition; Nikki Gemmell’s Shiver, the story of a young journalist who finds love and tragedy on an Antarctic journey Antigua & Barbuda Jamaica Kincaid’s novel Annie John, which recounts growing up in Antigua. -

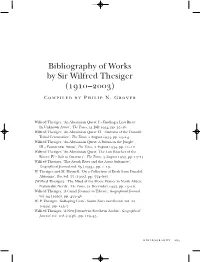

Bibliography of Works by Sir Wilfred Thesiger (1910–2003) Compiled by Philip N

Bibliography of Works by Sir Wilfred Thesiger (1910–2003) Compiled by Philip N. Grover Wilfred Thesiger, ‘An Abyssinian Quest: I – Finding a Lost River: In Unknown Aussa’, The Times, 31 July 1934, pp. 15–16. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘An Abyssinian Quest: II – Customs of the Danakil: Tribal Ceremonies’, The Times, 1 August 1934, pp. 13–14. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘An Abyssinian Quest: A Sultan in the Jungle: III – Fauna near Aussa’, The Times, 2 August 1934, pp. 11–12. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘An Abyssinian Quest: The Lost Reaches of the Rivers: IV – Salt as Currency’, The Times, 3 August 1934, pp. 13–14. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘The Awash River and the Aussa Sultanate’, Geographical Journal, vol. 85 (1935), pp. 1–19. W. Thesiger and M. Meynell, ‘On a Collection of Birds from Danakil, Abyssinia’, Ibis, vol. 77 (1935), pp. 774–807. [Wilfred Thesiger], ‘The Mind of the Moor: France in North Africa: Nationalist Needs’, The Times, 21 December 1937, pp. 15–16. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘A Camel Journey to Tibesti’, Geographical Journal, vol. 94 (1939), pp. 433–46. W. P. Thesiger, ‘Galloping Lion’, Sudan Notes and Records, vol. 22 (1939), pp. 155–7. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘A New Journey in Southern Arabia’, Geographical Journal, vol. 108 (1946), pp. 129–45. bibliography 269 W. Thesiger, ‘A Journey through the Tihama, the ‘Asir, and the Hijaz Mountains’, Geographical Journal, vol. 110 (1947), pp. 188–200. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘Empty Quarter of Arabia’, Listener, vol. 38 (1947), pp. 971–2. W. Thesiger, ‘Across the Empty Quarter’, Geographical Journal, vol. 111 (1948), pp. 1–19. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘Studies in the Southern Hejaz and Tihama’, Geographical Magazine, vol. -

RICHARD LONG Biography

SPERONE WESTWATER 257 Bowery New York 10002 T + 1 212 999 7337 F + 1 212 999 7338 www.speronewestwater.com RICHARD LONG Biography Born: l945, Bristol, England. Education: West of England College of Art, Bristol 1962-1965 St. Martin’s School of Art, London 1966-1968 Prizes and Awards: October 1988 Kunstpreis Aachen November 1989 Turner Prize June 1990 Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres July 1995 Doctor of Letters, honoris causa. University of Bristol January 1996 Wilhelm Lehmbruck-Preis, Duisburg September 2009 Praemium Imperiale Art Award December 2012 Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CDE), awarded by Queen Elizabeth II February 2015 Whitechapel Art Gallery Icon Award 2018 Commander of the British Empire for Services to Art Solo Exhibitions 1968 “Sculpture,” Konrad Fischer, Düsseldorf, 21 September – 18 October 1969 “Richard Long,” John Gibson, New York, 22 February – 14 March “Sculpture,” Yvon Lambert, Paris, 5 – 26 November “Richard J. Long,” Konrad Fischer, Düsseldorf, 5 July – 1 August “A Sculpture by Richard Long,” Galleria Lambert, Milan, 15 November – 1 December 1969-70 “Richard Long: Exhibition One Year,” Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, Germany, July 1969 – July 1970 l970 “Richard Long,” Dwan Gallery, New York, 3 – 29 October “4 Sculptures,” Städtisches Museum, Mönchengladbach, Germany, 16 July – 30 August “Eine Sculpture von Richard Long,” Konrad Fischer, Düsseldorf, 11 May – 9 June 1971 “Richard Long,” Gian Enzo Sperone, Turin, opened 13 April “Richard Long,” Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, -

General Gordon's Last Crusade: the Khartoum Campaign and the British Public William Christopher Mullen Harding University, [email protected]

Tenor of Our Times Volume 1 Article 9 Spring 2012 General Gordon's Last Crusade: The Khartoum Campaign and the British Public William Christopher Mullen Harding University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Mullen, William Christopher (Spring 2012) "General Gordon's Last Crusade: The Khartoum Campaign and the British Public," Tenor of Our Times: Vol. 1, Article 9. Available at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor/vol1/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Scholar Works at Harding. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tenor of Our Times by an authorized editor of Scholar Works at Harding. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENERAL GORDON'S LAST CRUSADE: THE KHARTOUM CAMPAIGN AND THE BRITISH PUBLIC by William Christopher Mullen On January 26, 1885, Khartoum fell. The fortress-city which had withstood an onslaught by Mahdist forces for ten months had become the last bastion of Anglo-Egyptian rule in the Sudan, represented in the person of Charles George Gordon. His death at the hands of the Mahdi transformed what had been a simple evacuation into a latter-day crusade, and caused the British people to re-evaluate their view of their empire. Gordon's death became a matter of national honor, and it would not go un avenged. The Sudan had previously existed in the British consciousness as a vast, useless expanse of desert, and Egypt as an unfortunate financial drain upon the Empire, but no longer. -

Visiting the Arabian Peninsula: a Brief Glimpse of Contemporary and Not-So-Contemporary Culture in KSA, Aka the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Visiting the Arabian Peninsula: A Brief Glimpse of Contemporary and Not-So-Contemporary Culture in KSA, aka the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Nicola Gray ‘I went to Southern Arabia only just in time.’ Wilfed Thesiger, introduction to Arabian Sands 1 ‘What new era had begun – what could they expect of the future? For how long could the men stand it? This night had passed, but what about the nights to come? No one asked these questions aloud, but they obsessed everyone… ’ Abdelrahman Munif, Cities of Salt 2 There are many moments in life when our conscience should subliminally nudge us to have a second thought about something about to be said or done, or just said or done. Such instances can be important to the small, domestic details of daily life and relationships, or meaningful at a much more macro-level. A recent invitation to visit the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia – aka KSA – as part of a ‘VIP programme of events’ of ‘leading art professionals and patrons’ prompted such a conscience nudge in the writer of this essayistic diary. Momentarily flattered to be addressed as a ‘leading art professional’ (to which I can make no claims whatsoever), there were, however, some immediate reservations about accepting. I like to think I have a personal political and social compass that will always veer towards opposition to acts of deep injustice and inhumane practices, and as far as KSA is concerned there were several considerations that pulled my internal compass needle quite far in that direction. There were, for example, the now confirmed reports of the particularly gruesome murder of a dedicated exiled Saudi journalist in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October 2018,3 and other media stories of imprisonments, disappearances, torture, beheadings and the discriminatory treatment of women in this conservatively religious society. -

Livelihoods, Power and Choice: The

JANUARY 2009 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice Livelihoods, Power and Choice: The Vulnerability of the Northern Rizaygat, Darfur, Sudan Helen Young, Abdal Monium Osman, Ahmed Malik Abusin, Michael Asher, Omer Egemi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, the authors would like to thank the communities for their warm welcome and hospitality, and for willingly answering our many questions in North and West Darfur. Access to those communities would not have been possible without the help and support of a wide range of individuals and institutions. We would like to thank the members of the Council for the Development of Nomads in Khartoum and also Al Massar Charity Organization for Nomads and Environmental Conservation in Khartoum and El Fasher. In Darfur, the two teams would like especially to thank all those who supported and guided us in our work in Al Fashir and Al Geneina, and, during our field work, special thanks go to our local guides, translator, and drivers. Particular thanks to the Shartay Sharty Eltayeb Abakora of Kebkabyia and to Elmak Sharif Adam Tahir for the time they have taken to meet with the team and for their valuable insights. Among the international community special thanks to Karen Moore of the United Nations Resident Coordinators Office and Brendan Bromwich, of the United Nations Environment Programme, whose particular hard work and encouragement ensured that this study became a reality. Thanks also to Margie Buchanan-Smith, Nick Brooks, James Morton, Derk Segaar, Jeremy Swift, and Brendan Bromwich who commented on the draft report. We also appreciate the written response from the Council of Nomads on the report summary, and also the comments from participants of the debriefing sessions and Khartoum mini-workshop. -

( Head Teacher) Bsc (Econ) University of Wales Aberystwyth

SECONDARY SCHOOL Name and Qualification John Evenson ( Head Teacher) BSc (Econ) University of Wales Aberystwyth MSc London School of Economics PGCE University of London NPQH (National professional qualification for Headteachers, The national College of Teaching - UK) [email protected] Razwana Kimutai ( Deputy Academics) BEd Hons - English Literature, Egerton University [email protected] Maurice Otieno ( Head of Year - Senior School), Economics Department BA (Hons) - Economics and Sociology University of Nairobi PGDE University of Nairobi MBA University of Nairobi [email protected].,ke Jane Akelola, (Head of Year - Middle SChool) , Geography Department BA University of Nairobi MA - Geography - University of Nairobi IGCSE training -University of Cambridge [email protected] Kira Channa (Head of Year - Junior School), Chemistry Department BSc (Hons) - Nutrition University of Nottingham CIE Teaching Diploma [email protected] Mathematics Judith Muthoni Njiru BEd (Hons)- Maths and Physics Kenyatta University [email protected] Art and Design Stephanie Hooper BA (Hons) - Textile Design West Surrey College of Art and Design, UK Diploma in Arts and Design CIE Teaching Diploma [email protected] Biology Simon Greenwell BSc (Hons)- Biology, University of Sussex PGCE, University of London MSc - Biology, Yale University [email protected] Meggy Henrietta BSc (Hons)- Biology, University of Leeds, UK PGCE- Science, University of Sunderland, UK Certificate in Dyslexia