The Ecology of the Mudhif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Possibilities of Restoring the Iraqi Marshes Known As the Garden of Eden

Water and Climate Change in the MENA-Region Adaptation, Mitigation,and Best Practices International Conference April 28-29, 2011 in Berlin, Germany POSSIBILITIES OF RESTORING THE IRAQI MARSHES KNOWN AS THE GARDEN OF EDEN N. Al-Ansari and S. Knutsson Dept. Civil, Mining and Environmental Engineering, Lulea University, Sweden Abstract The Iraqi marsh lands, which are known as the Garden of Eden, cover an area about 15000- 20000 sq. km in the lower part of the Mesopotamian basin where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers flow. The marshes lie on a gently sloping plan which causes the two rivers to meander and split in branches forming the marshes and lakes. The marshes had developed after series of transgression and regression of the Gulf sea water. The marshes lie on the thick fluvial sediments carried by the rivers in the area. The area had played a prominent part in the history of man kind and was inhabited since the dawn of civilization by the Summarian more than 6000 BP. The area was considered among the largest wetlands in the world and the greatest in west Asia where it supports a diverse range of flora and fauna and human population of more than 500000 persons and is a major stopping point for migratory birds. The area was inhabited since the dawn of civilization by the Sumerians about 6000 years BP. It had been estimated that 60% of the fish consumed in Iraq comes from the marshes. In addition oil reserves had been discovered in and near the marshlands. The climate of the area is considered continental to subtropical. -

Semantic Innovation and Change in Kuwaiti Arabic: a Study of the Polysemy of Verbs

` Semantic Innovation and Change in Kuwaiti Arabic: A Study of the Polysemy of Verbs Yousuf B. AlBader Thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics April 2015 ABSTRACT This thesis is a socio-historical study of semantic innovation and change of a contemporary dialect spoken in north-eastern Arabia known as Kuwaiti Arabic. I analyse the structure of polysemy of verbs and their uses by native speakers in Kuwait City. I particularly report on qualitative and ethnographic analyses of four motion verbs: dašš ‘enter’, xalla ‘leave’, miša ‘walk’, and i a ‘run’, with the aim of establishing whether and to what extent linguistic and social factors condition and constrain the emergence and development of new senses. The overarching research question is: How do we account for the patterns of polysemy of verbs in Kuwaiti Arabic? Local social gatherings generate more evidence of semantic innovation and change with respect to the key verbs than other kinds of contexts. The results of the semantic analysis indicate that meaning is both contextually and collocationally bound and that a verb’s meaning is activated in different contexts. In order to uncover the more local social meanings of this change, I also report that the use of innovative or well-attested senses relates to the community of practice of the speakers. The qualitative and ethnographic analyses demonstrate a number of differences between friendship communities of practice and familial communities of practice. The groups of people in these communities of practice can be distinguished in terms of their habits of speech, which are conditioned by the situation of use. -

S. RES. Preamble Calendar No

1 Calendar No. 304 103D CONGRESS 1ST SESSION S. RES. 167 RESOLUTION Expressing the sense of the Senate concerning the Iraqi Government's campaign against the Marsh Arabs of southern Iraq. NOVEMBER 18 (legislative day, NOVEMBER 2), 1993 Reported with an amendment and an amendment to the preamble III Calendar No. 304 103D CONGRESS 1ST SESSION S. RES. 167 Expressing the sense of the Senate concerning the Iraqi Government's campaign against the Marsh Arabs of southern Iraq. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES NOVEMBER 17 (legislative day, NOVEMBER 2), 1993 Mr. MOYNIHAN (for himself, Mr. PELL and Mr. HELMS) submitted the follow- ing resolution; which was referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations NOVEMBER 18 (legislative day, NOVEMBER 2), 1993 Reported by Mr. PELL, with an amendment and an amendment to the preamble [Omit the part struck through and insert the part printed in italic] RESOLUTION Expressing the sense of the Senate concerning the Iraqi Government's campaign against the Marsh Arabs of southern Iraq. Whereas the government of Saddam Hussein has a long and well documented history of brutal repression of the popu- lation of Iraq; Whereas Saddam Hussein carried out a methodical campaign of genocide against Iraqi Kurds, including extensive ef- forts to render large areas of Iraqi Kurdistan uninhabit- 1 2 able and the use of poison gas in violation of inter- national law; Whereas Saddam Hussein is now conducting a massive cam- paign of repression against the population of Shi'ite Arabs in southern Iraq known as the marsh Arabs or -

IRAQI REFUGEES, ASYLUM SEEKERS, and DISPLACED PERSONS: Current Conditions and Concerns in the Event of War a Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper

A Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper, February, 2003 IRAQI REFUGEES, ASYLUM SEEKERS, AND DISPLACED PERSONS: Current Conditions and Concerns in the Event of War A Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 2 I. HUMANITARIAN CONCERNS............................................................................................................. 3 A. CURRENT CONCERNS.............................................................................................................................3 B. BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................................................4 C. HUMAN RIGHTS OBLIGATIONS ...............................................................................................................5 II. INTERNALLY DISPLACED IRAQIS................................................................................................... 6 A. CURRENT CONCERNS.............................................................................................................................6 B. BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................................................7 C. HUMAN RIGHTS OBLIGATIONS ...............................................................................................................8 III. THE PROSPECTS FOR “SAFE AREAS” FOR INTERNALLY DISPLACED -

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE and HERITAGE Basra Its History, Culture and Heritage

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE CULTURE : ITS HISTORY, BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins Edited by Paul Collins BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins © BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ 2019 ISBN 978-0-903472-36-4 Typeset and printed in the United Kingdom by Henry Ling Limited, at the Dorset Press, Dorchester, DT1 1HD CONTENTS Figures...................................................................................................................................v Contributors ........................................................................................................................vii Introduction ELEANOR ROBSON .......................................................................................................1 The Mesopotamian Marshlands (Al-Ahwār) in the Past and Today FRANCO D’AGOSTINO AND LICIA ROMANO ...................................................................7 From Basra to Cambridge and Back NAWRAST SABAH AND KELCY DAVENPORT ..................................................................13 A Reserve of Freedom: Remarks on the Time Visualisation for the Historical Maps ALEXEI JANKOWSKI ...................................................................................................19 The Pallakottas Canal, the Sealand, and Alexander STEPHANIE -

Provincialdevelopment Strategy Missangovernorate

LADP in Iraq – Missan PDS Local Area Development Programme in Iraq Financed by the Implemented European Union by UNDP PROVINCIAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY MISSAN GOVERNORATE February 2018 LADP in Iraq – Missan PDS 2 LADP in Iraq – Missan PDS FOREWORD BY THE GOVERNOR … 3 LADP in Iraq – Missan PDS 4 LADP in Iraq – Missan PDS CONTENT PDS Missan Governorate Foreword by the Governor ............................................................................................................................... 3 Content ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................... 7 List of Tables .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 11 1. Purpose of the PDS ...................................................................................................................................... 11 2. Organisation of the PDS ............................................................................................................................. -

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management in the Iraqi Marshlands

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management in the Iraqi Marshlands Screening Study on Potential World Heritage Nomination Tobias Garstecki and Zuhair Amr IUCN REGIONAL OFFICE FOR WEST ASIA 1 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: IUCN ROWA, Jordan Copyright: © 2011 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Garstecki, T. and Amr Z. (2011). Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management in the Iraqi Marshlands – Screening Study on Potential World Heritage Nomination. Amman, Jordan: IUCN. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1353-3 Design by: Tobias Garstecki Available from: IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Regional Office for West Asia (ROWA) Um Uthaina, Tohama Str. No. 6 P.O. Box 942230 Amman 11194 Jordan Tel +962 6 5546912/3/4 Fax +962 6 5546915 [email protected] www.iucn.org/westasia 2 Table of Contents 1 Executive -

Arabian Sands Ebook

ARABIAN SANDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Wilfred Thesiger,Rory Stewart | 368 pages | 22 Jun 2011 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141442075 | English | London, United Kingdom Arabian Sands PDF Book I had found satisfaction in the stimulating harshness of this empty land, pleasure in the nomadic life which I had led. Read it Forward Read it first. Last, but not least, Thesiger is a good photographer, working well with black and white film to capture the desert landscape, the pure-bred camels, the faces of the tribesmen and the cities on the coast. The very slowness of our march diminished its monotony. Sometimes I counted my footsteps to a bush or to some other mark, and this number seemed but a trifle deducted from the sum that lay ahead of us. He learned their language, cared for them, and tried to understand their world. We then halted and, using the loads and camelsaddles, quickly built a small perimeter round our camp, which was protected on one side by the river. I read this book on a beach somewhere far away from the deserts of Arabia. It had been wildly exciting to charge with a mob of mounted tribesmen through thick bush after a galloping lion, to ride close behind it when it tired, while the Arabs waved their spears and shouted defiance, to circle round the patch of jungle in which it had come to bay, trying to make out its shape among the shadows, while the air quivered with its growls. Penguin Classics. When I say everything I really mean that, there's nothing that he is too embarrassed to discuss about camels or the Bedu for that matter. -

A Barren Legacy? the Arabian Desert As Trope in English Travel Writing, Post-Thesiger

A Barren Legacy? The Arabian Desert as Trope in English Travel Writing, Post-Thesiger Jenny Owen A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2020 Note on Copyright This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed to the owner of the Intellectual Property Rights. Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... 4 Introduction: Arabia, the Land of Legend ................................................................ 5 Locating Arabia ................................................................................................... 11 Studying Arabia as a country of the mind ............................................................. 18 The Lawrence and Thesiger legacy ...................................................................... 22 Mapping the thesis: an outline of the chapters ...................................................... 27 1. In Literary Footsteps: The Prevalence of -

Reference Code

THESIGER GB165-0545 Reference code: GB165-0545 Title: Sir Wilfred Thesiger Collection Name of creator: Thesiger, Sir Wilfred Patrick (1910-2003), Knight, Diplomat, Author and Traveller Dates of creation of material: c1954 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 27 magic lantern slides Biographical history: Thesiger, Sir Wilfred Patrick (1910-2003), Knight, Diplomat, Author and Traveller. Born 3 June 1910, son of Captain Wilfred Gilbert Thesiger and Kathleen Mary. Educated at Eton College and Magdalen College, Oxford University. Received a grant from the Royal Geographical Society in 1935 to explore the Aussa Sultanate and the country of Abyssinia between 1933-1934. Joined the Sudan Political Service and served in desert campaigns between 1935-1940. Joined the North and East African Campaign with rank of Major during World War II. Worked in Arabia with the Desert Locusts Research Organization between 1945-1949. Explored the Empty Quarter (desert of southern Arabia) between 1946-1950. From 1950 onwards, explored French West Africa, Iraq, Kurdistan, Pakistan, Persia and Kenya. Lived with Marsh Arabs in southern Iraq over seven years from 1950 to the Iraqi Revolution. Returned to England in 1994. Died 24 August 2003. Scope and content: 27 magic lantern slides of the Marsh Arabs in southern Iraq, c1954. The slides depict ethnological scenes of the Marsh Arabs’ communal life such as fishing, hunting, communal gatherings, landscape panoramic views and portraits. All of the slides are labelled ‘Royal Central Asian Society’ and the original packaging was labelled ‘?1954. Marsh Arabs W. Thesiger’. Access conditions: Open Language of material: English Conditions governing reproduction: There are no special restrictions on copying other than statutory regulations (UK Copyright law). -

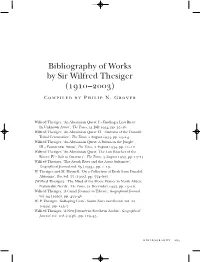

Bibliography of Works by Sir Wilfred Thesiger (1910–2003) Compiled by Philip N

Bibliography of Works by Sir Wilfred Thesiger (1910–2003) Compiled by Philip N. Grover Wilfred Thesiger, ‘An Abyssinian Quest: I – Finding a Lost River: In Unknown Aussa’, The Times, 31 July 1934, pp. 15–16. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘An Abyssinian Quest: II – Customs of the Danakil: Tribal Ceremonies’, The Times, 1 August 1934, pp. 13–14. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘An Abyssinian Quest: A Sultan in the Jungle: III – Fauna near Aussa’, The Times, 2 August 1934, pp. 11–12. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘An Abyssinian Quest: The Lost Reaches of the Rivers: IV – Salt as Currency’, The Times, 3 August 1934, pp. 13–14. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘The Awash River and the Aussa Sultanate’, Geographical Journal, vol. 85 (1935), pp. 1–19. W. Thesiger and M. Meynell, ‘On a Collection of Birds from Danakil, Abyssinia’, Ibis, vol. 77 (1935), pp. 774–807. [Wilfred Thesiger], ‘The Mind of the Moor: France in North Africa: Nationalist Needs’, The Times, 21 December 1937, pp. 15–16. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘A Camel Journey to Tibesti’, Geographical Journal, vol. 94 (1939), pp. 433–46. W. P. Thesiger, ‘Galloping Lion’, Sudan Notes and Records, vol. 22 (1939), pp. 155–7. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘A New Journey in Southern Arabia’, Geographical Journal, vol. 108 (1946), pp. 129–45. bibliography 269 W. Thesiger, ‘A Journey through the Tihama, the ‘Asir, and the Hijaz Mountains’, Geographical Journal, vol. 110 (1947), pp. 188–200. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘Empty Quarter of Arabia’, Listener, vol. 38 (1947), pp. 971–2. W. Thesiger, ‘Across the Empty Quarter’, Geographical Journal, vol. 111 (1948), pp. 1–19. Wilfred Thesiger, ‘Studies in the Southern Hejaz and Tihama’, Geographical Magazine, vol. -

Refugees from Iraq Their History, Cultures, and Background Experiences

COR Center Enhanced Refugee Backgrounder No. 1 October 2008 Refugees fromIraq COR Center Enhanced Refugee Backgrounder No. 1 October 2008 Refugees from Iraq Their History, Cultures, and Background Experiences Writers: Edmund Ghareeb, Donald Ranard, and Jenab Tutunji Editor: Donald A. Ranard Published by the Center for Applied Linguistics Cultural Orientation Resource Center Center for Applied Linguistics 4646 40th Street, NW Washington, DC 20016-1859 Tel. (202) 362-0700 Fax (202) 363-7204 http://www.culturalorientation.net http://www.cal.org The contents of this Backgrounder were developed with funding from the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, United States Department of State, but do not necessarily represent the policy of that agency and the reader should not assume endorsement by the federal government. The Backgrounder was published by the Center for Applied Linquistics (CAL), but the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of CAL. Production supervision: Sanja Bebic Writers: Edmund Ghareeb, Donald Ranard, and Jenab Tutunji Editor: Donald A. Ranard Copyediting: Jeannie Rennie Proofreading: Craig Packard Cover: Ellipse Design Design, illustration, production: Ellipse Design ©2008 by the Center for Applied Linguistics The U.S. Department of State reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and to authorize others to use, the work for Government purposes. All other rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to the Cultural Orientation Resource Center, Center for Applied Linguistics, 4646 40th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C.