Transformations the Transformation 4 of Jury Trial in Early Modern England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charging Language

1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abduction ................................................................................................73 By Relative.........................................................................................415-420 See Kidnapping Abuse, Animal ...............................................................................................358-362,365-368 Abuse, Child ................................................................................................74-77 Abuse, Vulnerable Adult ...............................................................................78,79 Accessory After The Fact ..............................................................................38 Adultery ................................................................................................357 Aircraft Explosive............................................................................................455 Alcohol AWOL Machine.................................................................................19,20 Retail/Retail Dealer ............................................................................14-18 Tax ................................................................................................20-21 Intoxicated – Endanger ......................................................................19 Disturbance .......................................................................................19 Drinking – Prohibited Places .............................................................17-20 Minors – Citation Only -

Gfniral Statutes

GFNIRAL STATUTES OF THE STATE OF MINNESOTA, IN FOROE JANUARY, 1891. VOL.2. CowwNnro ALL TEE LAw OP & GENERAJ NATURE Now IN FORCE AND NOT IN VOL. 1, THE SAME BEING TEE CODE OF Civu PROCEDURE AND ALL REME- DIAL LAW, THE PROBATE CODE, THE PENAL CODE AND THE CEnt- JRAL PROCEDURE, THE CoNSTITuTIoNS AND ORGANIc ACTS. COMPILED AND ANNOTATED BY JNO. F. KELLY, OF TUE Sr. Pui BAR. SECOND EDITION. ST. PAUL: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR 1891. A MINNESOTA STATUTES 1891 IN] EX To Vols. 1 and , except as Indicated by the cross-references, to Vol. 1. A - ACCOUNTS. (cqinued)-- officers'., of corporation, altering, §6448. ABANDONMNT (see CHILD)- presentation, of fraudulent, when felony, Qf, insane person, penalty fpr, §5895, §6507. of lands condemned for public use, §1229. ABATE- ACCOUN,T BOOKS- reognizance.not to abate, when, §439. • are p'rirna.facie evidence, §51'12. action to, nuisapee, §*442 ACCUSATION- actions abated when, §4738. to remove attorneys, §4376. board of health, sa,ll, hat,nuisapces, i9, %vriting. veiifipd, '4l77. §5SS, 589.. ACCUSED- warrant to, §591. rigMsof; §6626 ABBREViATIONS- iii describing lands, §1582. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (see Index to 'Vol. ABDUCTION (see SEDUCTION; KTDNAP- of 1eeds of land, §4121. RING)-. certifipa.te of. §4122. defined, pnnishment,f,or, §6196. ii qter.sta,tes, §4.23. evidence required to cnvitof, §6197. in foreign countries. §4124. ABETTING (see AIDIN-)- iefusaI to aknplege, §4125. ABOLISHED- proceedings to eompl, §4126. dower anl curtesy is, §4001.. defective, to, cqnveyanqes legalized-. certain defects legalized, §4164. ABORTION (see INDECENT ARTICLES)- ntnslapghter in first degree, when, by officer whose ternl. has çxpired, §4165, §6H5, GUll. -

![Chap. 10.] OFFENCES AGAINST PUBLIC JUSTICE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9302/chap-10-offences-against-public-justice-949302.webp)

Chap. 10.] OFFENCES AGAINST PUBLIC JUSTICE

Chap. 10.] OFFENCES AGAINST PUBLIC JUSTICE. CHAPTER X. OF OFFENCES AGAINST PUBLIC JUSTICE. THE order of our distribution will next lead us to take into consideration such crimes and misdemeanors as more especially affect the commonwealth, or public polity of the kingdom: which, however, as well as those which are pecul- iarly pointed against the lives and security of private subjects, are also offences against the king, as the pater-familiasof the nation: to whom it appertains by his regal office to protect the community, and each individual therein, from every degree of injurious violence, by executing those laws which the people them- selves in conjunction with him have enacted; or at least have consented to, by an agreement either expressly made in the persons of their representatives, or by a tacit and implied consent presumed from and proved by immemorial usage. The species of crimes which we have now before us is subdivided into such a number of inferior and subordinate classes, that it would much exceed the bounds of an elementary treatise, and be insupportably tedious to the reader, were I to examine them all minutely, or with any degree of critical accuracy. I shall therefore confine myself principally to general definitions, or descriptions of this great variety of offences, and to the punishments inflicted by law for each particular offence; with now and then a few incidental observations: referring the student for more particulars to other voluminous authors; who have treated of these subjects with greater precision and more in detail than is consistent with the plan of these Commentaries. -

Criminal Law. Merger of Conspiracy Into Completed

RECENT CASES the beneficial owners to avoid the statutory liability. Corker v. Soper 53 F. (2d) igo (C.C.A. 5th 1931); 45 Harv. L. Rev. 580 (1932). There, since, the holding did not con- sist of a majority of the shares, obviously no centralization of control of the company was intended. The parent company in the principal case can be distinguished in that its primary purpose was to centralize control. In both cases, however, the fact that the holding companies were inadequately financed to meet the contingent liability attach- ing to bank stock can be considered as indicating an attempted evasion of the statute. To determine when a holding company is so inadequately financed as to justify a dis- regard of the corporate entity to the extent of holding its stockholders personally liable, its assets must be carefully scrutinized. Since the purpose of the statute is to provide a "secondary" protection to depositors, equalling the stock of the depositary bank, it should not be considered an evasion if the assets of the holding company are sufficient to satisfy that contingent liability on the bank shares held. Thus, where a holding company has a wide and diversified portfolio consisting of many strong operat- ing companies amply sufficient to satisfy any contingent liability on bank stock held, there should be no reason to hold its shareholders personally liable. And it is conceiv- able that a parent company, whose sole assets are stocks in a large number of sub- sidiary banks widely distributed geographically, would be adequately financed to pro- tect creditors of failing banks by converting some of the stocks of their solvent banks into cash. -

Inchoate Offences Conspiracy, Attempt and Incitement 5 June 1973

N.B. This is a Working Paper circulated for comment and criticism only. It does not represent the final views. of the Law Commission. The Law Cominission will be grateful for comments before 1 January 1974. All correspondence should be addressed to: J.C. R. Fieldsend, Law Commission, Conquest Hoiis e, 37/38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WC1N 2BQ. (Tel: 01-242 0861, Ex: 47) The Law Commission Working Paper No 50 Inchoate Offences Conspiracy, Attempt and Incitement 5 June 1973 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE 1973 @ Crown copyright 1973 SBN 11 730081 0 THE LAW COMMISSION WORKING PAPER NO. 50 Second Programme, Item XVIII CODIFICATION OF THE CRIMINAL LAW GENERAL PRINCIPLES INCHOATE OFFENCES : CONSPIRACY, ATTEMPT AND INCITEMENT Introduction by the Law Commission 1. The Working Party' assisting the Commission in the examination of the general principles of the criminal law with a view to their codification has prepared this Working Paper on the inchoate offences. It is the fourth in a series' designed as a basis upon which to seek the views of those concerned with the criminal law. In pursuance of - its policy of wide consultation, the Law Commission is publishing the Working Paper and inviting comments upon it. 2. To a greater extent than in previous papers in this series the provisional proposals of the Working Party involve fundamental changes in the law which, we think, will prove much more controversial than those made in the other papers. The suggested limitation of the crime of conspiracy to 1. For membership see p. ix. 2. The others are "The Mental Element in Crime" (W.P. -

A Heport of the to the of the February 194-9

PENAL LAUS A Heport of the JOINT ST ;WE GOVEflNMEI\TT COHIHS:3ION to the GE~llirt1~ A8~EMBLY of the COHHONUEALTH OF PENNSYL1JAl'TIA February 194-9 LETTER OF TRAN3JvlITT AL To the Hembers of the General Assembly of the Common wealth of Pennsylvania: Pursuant to Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 113, Session of 19~7, we submit herewith a report dealing "lith the revision and codification of the penal laws. In accord,ance with Act No. ~, Session of 191+3, Section.'+, the Commission created a subcommittee to aid in the task assigned. On behalf of the Commission, the cooperation of the members of the subcommittee is gratefully acknmlledged. \Jeldon B. Heyburn, Chairman Joint state Government Commission Capitol Building Harrisburg, Pennsylvania February, 19 1+9 ii JOINT STATE GOVERN}lliNT CO]~;ISSION Honorable \'!eldon B. Heyburn, Chairman Honorable Baker Royer, Vice Chairman Honorable Herbert P. Sorg, Secretary-Treasurer Senate Members House Nembers Joseph 11. Barr Hiram G. Andrews Leroy E. Chapman Adam T. Bower John H. Dent Homer S. Brown Anthony J. DiSilvestro Charles H. Brunner, Jr. James A. Geltz Edwin C. E.ring Weldon B. Heyburn Ira T. Fiss Frederick L. Homsher Robert D. Fleming A. Evans Kephart IV. ,stuart Helm A. H. Letzler Earl E. Hewitt, Sr. John G. Snm/den Thomas H. Lee O. J. Tallman Albert S. Readinger M. Harvey Taylor Baker Royer John N. Hall:er Herbert P. Sorg Guy IJ. Davis, Counsel and Director Paul H. Wueller, Associate Director in Charge of Research and Statistics L. D. Stambaugh, Hesident Secretary f~toinette S. Giddings, Administrative Assistant iii JOINT STATE GOVER~~NT COW1IS3ION SUBCOl'fllITTEE ON PENAL LAWS AND CRIMINAL PROCEDURE Honorable John W. -

The Code of the State of Georgia

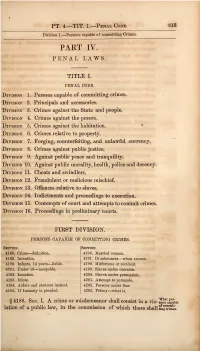

PT. 4.—TIT. 1.—Penal Code. 813 Division 1. —Persons capable of committing Crimes. PART IV. PENAL LAWS. TITLE I. PENAL CODE. Division 1. Persons capable of committing crimes. Division 2. Principals and accessories. Division 3. Crimes against the State and people. • Division 4. Crimes against the person. • Division 5. Crimes against the habitation. Division 6. Crimes relative to property. Division 7. Forging, counterfeiting, and unlawful currency. Division 8. Crimes against public justice. Division 9. Against public peace and tranquility. Division 10. Against public morality, health, police and decency. Division 11. Cheats and swindlers. Division 12. Fraudulent or malicious mischief. Division 13. Offences relative to slaves. Division 14. Indictments and proceedings to execution. Division 15. Contempts of court and attempts to commit crimes. Division 16. Proceedings in preliminary courts. FIKST DIYISIOK , PERSONS CAPABLE OF COMMITTING CRIMES. Section. Section. 4188. Crime—definition. 4196. Married women. 4189. Intention. 419*7. Drunkenness—when excuse. 4190. Infants, 14 years—liable. 4198. Misfortune or accident. 4191. Under 10—incapable. 4199. Slaves under coercion. 4192. Lunatics. 4200. Slaves under persuasion. 4193. Idiots. 4201. Attempt to persuade. 4194. Aiders and abettors instead. 4202. Persons under fear. 4195. If Insanity is pleaded. 4203. Felony—what is. § 4188. Sec. I. A crime or misdemeanor shall consist in a vio- Salable of commit- in the lation of a public law, commission of which there shall tinjS crimes. 814 PT. 4.—TIT. 1.—Penal Code. Division 1. —Persons capable of committing Crimes. be an union or joint operation of act and intention, or criminal negligence. Intention, § 4189. Sec. II. Intention will be manifested by the circum- stances connected with the perpetration of the offence, and the sound mind and discretion of the person accused. -

Criminal Law

The Law Commission Working Paper No 62 Criminal Law Offences relating to the Administration of Justice LONDON HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 0 Crown copyright 7975 First published 7975 ISBN 0 11 730093 4 17-2 6-2 6 THE LAW COMMISSXON WORKING PAPER NO. 62 CRIMINAL LAW OFFENCES RELATING TO THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE CONTENTS Paras. I INTRODUCTION 1- 7 1 I1 PRESENT LAW 8- 25 5 Common Law 8- 17 5 Perverting the course of justice 8- 11 5 Examples of conspiracy charges 12- 13 8 Contempt of Court 14- 15 10 Escape and avoiding trial 16 11 Agreeing to indemnify bail 17 11 Statute ~aw 19- 25 12 Perjury 19- 20 12 Other statutory offences 21- 24 13 Summary 25 15 I11 PROPOSALS FOR REFORM 26-116 16 General 26- 33 16 Relationship with contempt of court 27- 29 17 Criminal and civil proceedings 30- 33 18 Outline of proposed offences 34- 37 20 1. Offences relating to all proceedings 38- 88 21 (i) Perjury 38- 60 21 iii Paras. Page Ihtroductory 38- 45 21 Should perjury be confined to false statements? 46 24 Oral evidence not on oath 47- 53 25 Extra-curial unsworn statements admissible as evidence 51- 59 28 Summary 60 31 (ii) Tampering with or fabricating evidence 61- 65 32 (iii)Preventing the attendance of witnesses 66- 67 34 (iv) Intimidation of a party 68- 84 35 (v) Improperly influencing a court 85- 91 43 2. Offences relating only to criminal matters 92-107 45 (i) Impeding the investigation of crime 93-101 45 (ii) Avoiding trial 102-105 50 (iii)Agreeing to indemnify bail 106-110 52 3. -

2014 CCH OFFENSE CODES Including New Felonies and Misdemeanors

2014 CCH OFFENSE CODES Including New Felonies and Misdemeanors RETIRED/ EXPIRED CODE STATUTE SEV SHORT DESCRIPTION LONG DESCRIPTION STATUS DATE ACTIVE DATE CRIMINAL CRIMINAL SOLICITATION/ATTEMPT/CONSPIRACY/ SOLICITATION/ATTEMPT/CONSPIRACY/T 0000 35 X TOOLS OOLS RETIRED 8/7/2007 1/1/1900 0001 X STATED CHARGE NOT CLEAR STATED CHARGE NOT CLEAR RETIRED 8/7/2007 1/1/1900 0002 X ARREST DATA NOT RECEIVED ARREST DATA NOT RECEIVED RETIRED 8/7/2007 1/1/1900 0008 16-4-7(B) F CRIMINAL SOLICITATION CRIMINAL SOLICITATION ACTIVE 1/1/1900 CRIMINAL ATTEMPT TO COMMIT A CRIMINAL ATTEMPT TO COMMIT A 0009 16-4-1 M MISDEMEANOR MISDEMEANOR ACTIVE 1/1/1900 0010 16-4-1 X CRIMINAL ATTEMPT CRIMINAL ATTEMPT RETIRED 8/7/2007 1/1/1900 CRIMINAL ATTEMPT TO COMMIT A CRIMINAL ATTEMPT TO COMMIT A 0011 16-4-1 F FELONY FELONY ACTIVE 1/1/1900 0012 16-4-8 X CRIMINAL CONSPIRACY CRIMINAL CONSPIRACY RETIRED 8/7/2007 1/1/1900 CONSPIRACY TO COMMIT A CONSPIRACY TO COMMIT A 0013 16-4-8 M MISDEMEANOR MISDEMEANOR ACTIVE 1/1/1900 POSSESSION OF TOOLS FOR POSSESSION OF TOOLS FOR COMMISSION 0014 16-7-20 F COMMISSION OF A CRIME OF A CRIME ACTIVE 1/1/1900 0015 16-4-8 F CONSPIRACY TO COMMIT A FELONY CONSPIRACY TO COMMIT A FELONY ACTIVE 1/1/1900 0016 16-4-10 F DOMESTIC TERRORISM - FELONY DOMESTIC TERRORISM - FELONY ACTIVE 5/16/2002 0100 X TREASON TREASON RETIRED 8/7/2007 1/1/1900 0101 16-11-1 F TREASON TREASON ACTIVE 1/1/1900 ADVOCATING OVERTHROW OF ADVOCATING OVERTHROW OF 0109 16-11-4 F GOVERNMENT GOVERNMENT ACTIVE 1/1/1900 0115 16-11-3 F INCITING TO INSURRECTION INCITING TO INSURRECTION -

Effective 10/01/2019

1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abduction ................................................................................................73 By Relative.........................................................................................415-420 See Kidnapping Abuse, Animal ...............................................................................................358-362,365-368 Abuse, Child ................................................................................................74-77 Abuse, Vulnerable Adult ...............................................................................78,79 Accessory After The Fact ..............................................................................38 Adultery ................................................................................................357 Aircraft Explosive............................................................................................455 Alcohol AWOL Machine.................................................................................19,20 Retail/Retail Dealer ............................................................................14-18 Tax ................................................................................................20-21 Intoxicated – Endanger ......................................................................19 Disturbance .......................................................................................19 Drinking – Prohibited Places .............................................................17-20 Minors – Citation Only -

Conceptualizing Inchoate Complicity: the Normative and Doctrinal Case for Lesser Offenses As an Alternative to Complicity Liability

Document1 (Do Not Delete) 5/10/2016 8:15 PM CONCEPTUALIZING INCHOATE COMPLICITY: THE NORMATIVE AND DOCTRINAL CASE FOR LESSER OFFENSES AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO COMPLICITY LIABILITY DENNIS J. BAKER* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 504 II. HISTORY AND DOCTRINE .............................................................. 509 III. THE LETTER OF THE LAW UNDER THE SERIOUS CRIME ACT 2007 .......................................................................................................... 514 IV. RECKLESSLY ENCOURAGING AND ASSISTING SEVERAL AND ALTERNATIVE CRIMES ........................................................................ 532 V. ENCOURAGING AND ASSISTING AN INNOCENT AGENT .................................................................................................................. 537 VI. CAUSATION, ACT CAPABLENESS, AND IMPOSSIBILITY ....... 540 VII. IMPOSSIBILITY AND CAPABILITY ............................................ 552 VIII. WHEN IS TRIVIAL ENCOURAGEMENT CAPABLE OF ENCOURAGING? ................................................................................... 557 IX. ATTEMPTS TO ATTEMPT AND THE SERIOUS CRIME ACT 2007 .................................................................................................................. 566 X. REMOTE ENCOURAGEMENT ........................................................ 575 XI. CONCLUSION .................................................................................. 586 * (M.Phil., Ph.D. -

General Statutes

THE GENERAL STATUTES OF THE STATE OF MINNESOTA As Amended by Subsequent Legislation, with which are Incorporated All General Laws of the State in Force December 31, 1894 COMPILED AND EDITED BY HENRY B. WENZELL, Assisted by EUGENE P. LANE WITH ANNOTATIONS BY FRANCIS B. TIFFANY and Others AND A GENERAL INDEX BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE NATIONAL REPORTER SYSTEM COMPLETE IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. 2 CONTAINING Sections 4822 to 8054 of the General Statutes, and the General Index I ST. PAUL, MINN. 1 WEST PUBLISHING CO. ; 1S94 MINNESOTA STATUTES 1894 § 6285 PENAL CODE, AND ALLIED ACTS. £Ch. 92a [CHAPTER 92a.] [PENAL CODE, AND A T.T.TED ACTS.]1 Preliminary Provisions, g§ 6286-6297. 1. Persons Punishable for Crime, §§ 6298-6803. 2. Of Parties to Crime, §§ 6809-6314. 3. Degrees in the Commission of Crimes, and Attempts to Commit Crimes, SS 6315- 6317. 4. Treason, §§ 6318-6323. 5. Of Crimes against the Elective Franchise, § 6824. 6. Of Crimes by and against the Executive Power of the State, §§ 6825-6338. 7. Of Crimes against the Legislative Power, §§ 6339-6347. 8. Of Crimes against Public Justice, §g 6848-6425. (1) Bribery and Corruption, §§ 6348-6857. (2) Rescues, §§ 6358, 6359. (d) Escapes, and Aiding Therein, §§ 6360-6368. (4) Forging, Stealing, Mutilating, and Falsifying Judicial and Publio Records and Documents, §§ 6369, 6370. (5) Perjury and Subornation of Perjury, §§ 6371-6380. (6) Falsifying Evidence, §§ 6381-6386. (7) Other Offenses against Public Justice, §§ 6387-6422. (8) Conspiracy, §§ 6423-6425. 9. Of Crimes against the Person, §§ 6426-6509. (1) Suicide, §§ 6426-6432. (2) Homicide, §§ 6433-6461.