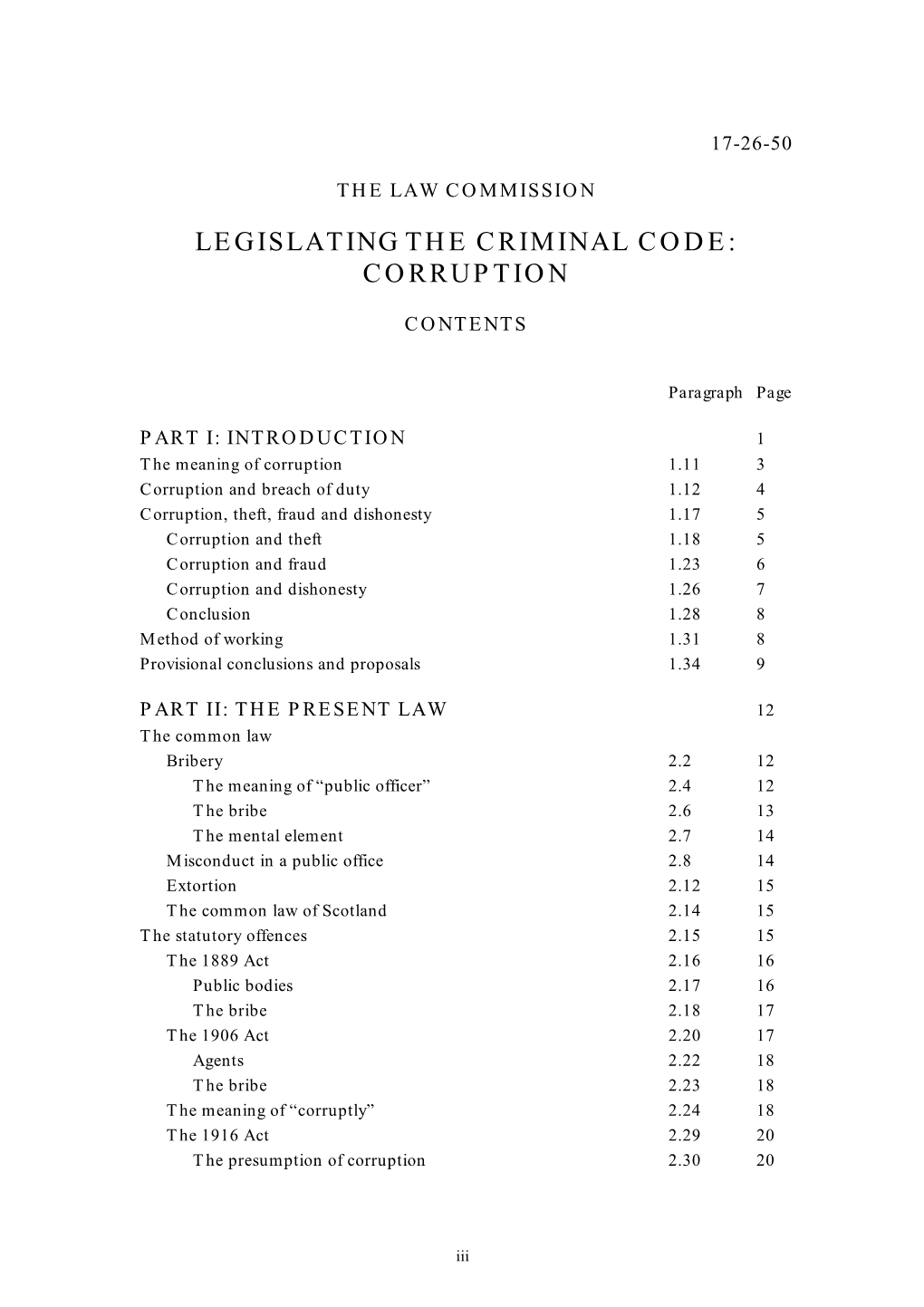

Legislating the Criminal Code: Corruption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charging Language

1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abduction ................................................................................................73 By Relative.........................................................................................415-420 See Kidnapping Abuse, Animal ...............................................................................................358-362,365-368 Abuse, Child ................................................................................................74-77 Abuse, Vulnerable Adult ...............................................................................78,79 Accessory After The Fact ..............................................................................38 Adultery ................................................................................................357 Aircraft Explosive............................................................................................455 Alcohol AWOL Machine.................................................................................19,20 Retail/Retail Dealer ............................................................................14-18 Tax ................................................................................................20-21 Intoxicated – Endanger ......................................................................19 Disturbance .......................................................................................19 Drinking – Prohibited Places .............................................................17-20 Minors – Citation Only -

British Deficiencies in Relation to American Clarity in International Anti-Corruption Law

GREASING THE WHEELS: BRITISH DEFICIENCIES IN RELATION TO AMERICAN CLARITY IN INTERNATIONAL ANTI-CORRUPTION LAW Todd Swanson* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. CORRUPTION: A ROUTINE PRACTICE, BUT NOT FOR LONG ...... 399 II. AMERICA'S CORRUPTION LEGACY: FROM NIXON'S SHAME TO CLINTON'S TRIUMPH ................................... 402 A. Watergate: Tricky Dick Opens America's Eyes and Congress Reacts .................................... 402 B. Clinton 's Less Noted, but ImportantLegacy: Making InternationalAnti-Corruption Law a Priority ............. 403 C. Building InternationalConsensus: Other International OrganizationsBegin to Make Law ...................... 405 D. The Capstone of the InternationalAnti-Bribery Movement: The OECD Convention ............................... 406 E. Making Sure States Keep Their Promises: The OECD Working Group on Anti-Bribery in International Business Transactions ............................... 407 III. AGREE TO DISAGREE: AMERICAN AND BRITISH IMPLEMENTATION OF THE OECD CONVENTION .............. 408 A. The United States' FightAgainst Corruption: The Foreign CorruptPractices Act and American Implementation of the OECD Convention ................ 408 1. Who Cannot Offer Bribes Under FCPA? .............. 408 2. Who Must One Bribe to Be Convicted Under the F CPA ? ......................................... 409 3. What Acts Constitute Bribes Under the FCPA? ......... 410 * J.D., University of Georgia School of Law, 2007; Certificate of European Law Studies from the Universit6 Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium, 2005; B.S., Psychology, B.A., Political Science, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, 2004. To my parents-thank you for all the love and support. GA. J. INT'L & COMP. L. [Vol. 35:397 4. What Level of Intent Is Required by the FCPA? ......... 411 5. Affirmative Defenses Under the FCPA ................ 412 6. Complicity in Bribery as Covered Under U.S. Law ...... 413 7. What Sanctions Do Violators of the FCPA Face? ...... -

Criminal Procedure in England and the United States: Comparisons in Initiating Prosecutions

Fordham Law Review Volume 49 Issue 1 Article 8 1980 Criminal Procedure in England and the United States: Comparisons in Initiating Prosecutions Irving R. Kaufman Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Digital Par t of the Law Commons Commons Network Recommended Citation Logo Irving R. Kaufman, Criminal Procedure in England and the United States: Comparisons in Initiating Prosecutions, 49 Fordham L. Rev. 26 (1980). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol49/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Criminal Procedure in England and the United States: Comparisons in Initiating Prosecutions Cover Page Footnote Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit; Chief Judge (1973-1980). District Court Judge (1949-1961) and Assistant United States Attorney (1935-1940) in the Southern District of New York. Chairman of the Executive Committee and former President of the Institute of Judicial Administration. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol49/iss1/8 CRIMINAL PROCEDURE IN ENGLAND AND THE UNITED STATES: COMPARISONS IN INITIATING PROSECUTIONS IRVING R. KAUFMAN* THE legal institutions of Great Britain have long served as the well-spring of American law. In drafting the Federal Constitution, the framers embellished British conceptions of a government of sepa- rated powers,' and drew on the enactments of Parliament. -

Comment Letter on File No. S7-12-06

1 Nancy Morris 8/29/06 Secretary Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, DC RE: Amendments to Regulation SHO (Release No. 34-54154 File No. S7-12-06) Ms. Morris and SEC Commissioners, My name is Dr. Jim DeCosta and I thank you for this opportunity to comment on these much-needed amendments to Reg SHO. In studying the 51-page circular attached to the proposed amendments I can see that the SEC has put in a great deal of time and thought into this process and your efforts have been duly noted by the investment community and are greatly appreciated. On the other hand though I see that there are those among you that still don’t appreciate the pandemic nature of this systemic “Fraud on the market” or the emergent nature of it as victimized corporations are drowning today in a sea of unaddressed and archaic delivery failures. These unaddressed delivery failures have in turn procreated often unexercisable “Share entitlements” that nearly all investors believe to be legitimate “Shares” that they can vote and receive tax preferential treatment of cash dividends from. Nothing could be further from the truth, however, yet these mere “Share entitlements” are readily sellable as if they were legitimate shares and are capable of inflicting massive dilutional damage upon the share structures of targeted corporations when their numbers and their lifespan are not scrutinized meticulously and kept in check as per the Congressional Mandate of the DTCC management. I’d like to make some suggestions starting in more of a macro sense and then follow it up with some specific suggestions as to amending Reg SHO. -

A Rationale of Criminal Negligence Roy Mitchell Moreland University of Kentucky

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 32 | Issue 2 Article 2 1944 A Rationale of Criminal Negligence Roy Mitchell Moreland University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Moreland, Roy Mitchell (1944) "A Rationale of Criminal Negligence," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 32 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol32/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RATIONALE OF CRIMINAL NEGLIGENCE (Continued from November issue) RoY MOREL A D* 2. METHODS Op DESCRIBING THE NEGLIGENCE REQUIRED 'FOR CRIMINAL LIABILITY The proposed formula for criminal negligence describes the higher degree of negligence required for criminal liability as "conduct creating such an unreasonable risk to life, safety, property, or other interest for the unintentional invasion of which the law prescribes punishment, as to be recklessly disre- gardful of such interest." This formula, like all such machinery, is, of necessity, ab- stractly stated so as to apply to a multitude of cases. As in the case of all abstractions, it is difficult to understand without explanation and illumination. What devices can be used to make it intelligible to judges and juries in individual cases q a. -

Imagereal Capture

Some Aspects of Theft of Computer Software by M. Dunning I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this paper is to test the capability of New Zealand law to adequately deal with the impact that computers have on current notions of crimes relating to property. Has the criminal law kept pace with technology and continued to protect property interests or is our law flexible enough to be applied to new situations anyway? The increase of the moneyless society may mean a decrease in money motivated crimes of violence such as robbery, and an increase in white collar crime. Every aspect of life is being computerised-even our per sonality is on character files, with the attendant )ossibility of criminal breach of privacy. The problems confronted in this area are mostly definitional. While it may be easy to recognise morally opprobrious conduct, the object of such conduct may not be so easily categorised as criminal. A factor of this is a general lack of understanding of the computer process, so this would seem an appropriate place to begin the inquiry. II. THE COMPUTER Whiteside I identifies five key elements in a computer system. (1) Translation of data into a form readable by the computer, called input; and subject to manipulation by the introduction of false data. Remote terminals can be situated anywhere outside the cen tral processing unit (CPU), connected by (usually) telephone wires over which data may be transmitted, e.g. New Zealand banks on line to Databank. Outside users are given a site code number (identifying them) and an access code number (enabling entry to the CPU) which "plug" their remote terminal in. -

Common Law Fraud Liability to Account for It to the Owner

FRAUD FACTS Issue 17 March 2014 (3rd edition) INFORMATION FOR ORGANISATIONS Fraud in Scotland Fraud does not respect boundaries. Fraudsters use the same tactics and deceptions, and cause the same harm throughout the UK. However, the way in which the crimes are defined, investigated and prosecuted can depend on whether the fraud took place in Scotland or England and Wales. Therefore it is important for Scottish and UK-wide businesses to understand the differences that exist. What is a ‘Scottish fraud’? Embezzlement Overview of enforcement Embezzlement is the felonious appropriation This factsheet focuses on criminal fraud. There are many interested parties involved in of property without the consent of the owner In Scotland criminal fraud is mainly dealt the detection, investigation and prosecution with under the common law and a number where the appropriation is by a person who of statutory offences. The main fraud offences has received a limited ownership of the of fraud in Scotland, including: in Scotland are: property, subject to restoration at a future • Police Service of Scotland time, or possession of property subject to • common law fraud liability to account for it to the owner. • Financial Conduct Authority • uttering There is an element of breach of trust in • Trading Standards • embezzlement embezzlement making it more serious than • Department for Work and Pensions • statutory frauds. simple theft. In most cases embezzlement involves the appropriation of money. • Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service. It is important to note that the Fraud Act 2006 does not apply in Scotland (apart from Statutory frauds s10(1) which increases the maximum In addition there are a wide range of statutory Investigating fraud custodial sentence for fraudulent trading to offences which are closely related to the 10 years). -

Legitimizing Pay to Play: Marketizing Radio Content Through a Responsive Auction Mechanism

LEGITIMIZING PAY TO PLAY: MARKETIZING RADIO CONTENT THROUGH A RESPONSIVE AUCTION MECHANISM Alon Rotem* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 130 II. RADIO REGULATION BACKGROUND / HISTORY ........ 131 A. Government Enforced Public Interest Standards...... 131 B. Marketization of the Public Interest Doctrine ........ 133 C. The Impact of the 1996 Telecommunications Act on License Renewals .................................... 134 III. PAYOLA RULES ............................................ 135 A. Payola Rules Impact on the Recording Industry ...... 136 B. A Brief History of Payola Transgressions ............ 137 C. Falloutfrom Recent Payola Prosecution .............. 139 D. Modern Payola Rules Ambiguity ..................... 139 IV. IMPACT OF TECHNOLOGY AND AUCTIONS ON BROAD- CAST SCARCITY ............................................ 140 A. The Rise and Evolution of Technology-Driven A uctions ....... ..................................... 141 B. Applying the Auction Mechanism to Radio Content Programm ing ........................................ 141 * J.D. Candidate 2007, University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law. B.S. Managerial Economics, 2001, University of California, Davis. I would like to thank my wife, Nicole, parents, Doron and Batsheva, and brothers, Tommy and Jonathan for their love, support, and encouragement. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Howard Shelanski for his wisdom and guidance in the "Telecommunications Law & Policy" class for which this comment was written. Special thanks to Paul Cohune, who has generously de- voted his time to editing this and virtually every paper I have written in the last 10 years, to Zach Katz for sharing his profound knowledge of the music industry, and to my future col- leagues at Ropes & Gray, LLP. I am also very grateful for the assistance of the editors of the UCLA Entertainment Law Review. Mr. Rotem welcomes comments at alon.rotem@ gmail.com. -

Squatting – the Real Story

Squatters are usually portrayed as worthless scroungers hell-bent on disrupting society. Here at last is the inside story of the 250,000 people from all walks of life who have squatted in Britain over the past 12 years. The country is riddled with empty houses and there are thousands of homeless people. When squatters logically put the two together the result can be electrifying, amazing and occasionally disastrous. SQUATTING the real story is a unique and diverse account the real story of squatting. Written and produced by squatters, it covers all aspects of the subject: • The history of squatting • Famous squats • The politics of squatting • Squatting as a cultural challenge • The facts behind the myths • Squatting around the world and much, much more. Contains over 500 photographs plus illustrations, cartoons, poems, songs and 4 pages of posters and murals in colour. Squatting: a revolutionary force or just a bunch of hooligans doing their own thing? Read this book for the real story. Paperback £4.90 ISBN 0 9507259 1 9 Hardback £11.50 ISBN 0 9507259 0 0 i Electronic version (not revised or updated) of original 1980 edition in portable document format (pdf), 2005 Produced and distributed by Nick Wates Associates Community planning specialists 7 Tackleway Hastings TN34 3DE United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)1424 447888 Fax: +44 (0)1424 441514 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nickwates.co.uk Digital layout by Mae Wates and Graphic Ideas the real story First published in December 1980 written by Nick Anning by Bay Leaf Books, PO Box 107, London E14 7HW Celia Brown Set in Century by Pat Sampson Piers Corbyn Andrew Friend Cover photo by Union Place Collective Mark Gimson Printed by Blackrose Press, 30 Clerkenwell Close, London EC1R 0AT (tel: 01 251 3043) Andrew Ingham Pat Moan Cover & colour printing by Morning Litho Printers Ltd. -

VICTORIA LAW FOUNDATION LAW ORATION Banco Court, Supreme

VICTORIA LAW FOUNDATION LAW ORATION Banco Court, Supreme Court of Victoria —21 July 2016 OF MOZART, MODERN DRAFTING AND THE CRIMINAL LAWYERS’ LAMENT Justice Mark Weinberg1 1 May I begin by thanking the Victoria Law Foundation for having organised this evening’s event. It is an honour to have been invited to speak to you tonight. I am, of course, conscious of the fact that among previous presenters in this series have been a number of great legal luminaries. 2 I have no doubt that some of you have come here this evening for one reason only. That is to see how, if at all, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, perhaps the greatest musical genius of all time, can legitimately be linked to a subject as soporific as modern drafting, still less to a subject as parochial as the ongoing grievances of the criminal bar. 3 There will be cynics among you who believe that I have included Mozart in the title of this paper simply to bolster the attendance tonight. As I hope to demonstrate, you are mistaken. You will have to wait in order to find out why. 4 As the Munchkins said to Dorothy, ‘It is always best to start at the beginning’. In my case, that was as a law student, almost exactly 50 years ago. It was then, under the expert guidance of a great teacher, Professor Louis Waller, that I first came across the tragic tale of Messrs Dudley and Stephens, and the events surrounding the shipwreck of the yacht Mignonette. Since that time, I have been both intrigued and fascinated by the criminal law. -

Criminal Law: Conspiracy to Defraud

CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD LAW COMMISSION LAW COM No 228 The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 228) CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD Item 5 of the Fourth Programme of Law Reform: Criminal Law Laid before Parliament bj the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to sc :tion 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 December 1994 LONDON: 11 HMSO E10.85 net The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Brooke, Chairman Professor Andrew Burrows Miss Diana Faber Mr Charles Harpum Mr Stephen Silber QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION 1.1 1 A. Background to the report 1. Our work on conspiracy generally 1.2 1 2. Restrictions on charging conspiracy to defraud following the Criminal Law Act 1977 1.8 3 3. The Roskill Report 1.10 4 4. The statutory reversal of Ayres 1.11 4 5. Law Commission Working Paper No 104 1.12 5 6. Developments in the law after publication of Working Paper No 104 1.13 6 7. Our subsequent work on the project 1.14 6 B. A general review of dishonesty offences 1.16 7 C. Summary of our conclusions 1.20 9 D. -

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 December 13, 2007 DA 07-4925 In Reply Refer to: 1800B3-RDH Released: December 14, 2007 Mr. Mark N. Lipp, Esq. Wiley Rein LLP 1776 K Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20006 In re: Multicultural Radio Broadcasting Licensee, LLC Station KAZN(AM), Pasadena, California Facility ID No. 51426 File No. BR-20050801CWN Multicultural Radio Broadcasting Licensee, LLC Station KAHZ(AM), Pomona, California Facility ID No. 61814 File No. BR-20050801CVN Polyethnic Broadcasting Licensee, LLC1 Station KMRB(AM), San Gabriel, California Facility ID No. 52913 File No. BR-20050801DCK Informal Objections to Applications for License Renewal Dear Mr. Lipp: This letter concerns the above-noted applications (collectively, the “Applications”) filed by Multicultural Radio Broadcasting Licensee, LLC to renew its licenses for Stations KAZN(AM), Pasadena, California and KAHZ(AM), Pomona, California, and by Polyethnic Broadcasting Licensee, LLC to renew its license for Station KMRB(AM), San Gabriel, California (collectively, the “Stations”). Also before us are three separate Informal Objections filed on October 31, 2005, by Liu-Chun Lin 1 Polyethnic Broadcasting Licensee, LLC, was the Licensee of Station KMRB(AM) at the time of the filing of the instant application for renewal of station license. On November 27, 2006, an Application for Consent to Assign Broadcast Station Construction Permit or License (BAL-20061114ADK) was granted by the Commission. Pursuant to this application, the License for Station KMRB(AM) was voluntarily assigned from Polyethnic Broadcasting Licensee, LLC, to Multicultural Radio Broadcasting Licensee, LLC. Both entities are controlled by the same individual and the assignment was sought as part of the merger of these two entities.