Independent Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

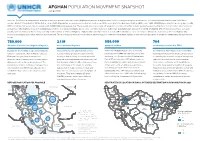

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations No

TURUN YLIOPISTON MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY OF UNIVERSITY OF TURKU MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOS DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations Patterns Migration in Iran: Afghans No. 14 TURUN YLIOPISTON MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS FROM THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF TURKU No. 1. Jukka Käyhkö and Tim Horstkotte (Eds.): Reindeer husbandry under global change in the tundra region of Northern Fennoscandia. 2017. No. 2. Jukka Käyhkö och Tim Horstkotte (Red.): Den globala förändringens inverkan på rennäringen på norra Fennoskandiens tundra. 2017. No. 3. Jukka Käyhkö ja Tim Horstkotte (doaimm.): Boazodoallu globála rievdadusaid siste Davvi-Fennoskandia duottarguovlluin. 2017. AFGHANS IN IRAN: No. 4. Jukka Käyhkö ja Tim Horstkotte (Toim.): Globaalimuutoksen vaikutus porotalouteen Pohjois-Fennoskandian tundra-alueilla. 2017. MIGRATION PATTERNS No. 5. Jussi S. Jauhiainen (Toim.): Turvapaikka Suomesta? Vuoden 2015 turvapaikanhakijat ja turvapaikkaprosessit Suomessa. 2017. AND ASPIRATIONS No. 6. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Asylum seekers in Lesvos, Greece, 2016-2017. 2017 No. 7. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Asylum seekers and irregular migrants in Lampedusa, Italy, 2017. 2017 Nro 172 No. 8. Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Katri Gadd & Justus Jokela: Paperittomat Suomessa 2017. 2018. Salavati Sarcheshmeh & Bahram Eyvazlu Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Davood No. 9. Jussi S. Jauhiainen & Davood Eyvazlu: Urbanization, Refugees and Irregular Migrants in Iran, 2017. 2018. No. 10. Jussi S. Jauhiainen & Ekaterina Vorobeva: Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Jordan, 2017. 2018. (Eds.) No. 11. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Refugees and Migrants in Turkey, 2018. 2018. TURKU 2008 ΕήΟΎϬϣΕϼϳΎϤΗϭΎϫϮ̴ϟϥήϳέΩ̶ϧΎΘδϧΎϐϓϥήΟΎϬϣ ISBN No. -

REFUGEES Rn Lran* by Il Hobin Shorish University of Illinois At

Bismiallah THE AFGHAt! REFUGEES rn lRAN* by i.l. Hobin Shorish University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Throughout the recent histories of Iran and Afghanistan refugees of one form or another have existed in each of these lands. Political and religious refugees have almost always constituted the majority of those who sought either Afghanistan or Iran as their new haven. The most recent Iranian wave of refugees in the Khurasan area of Afghanistan (Herat) has been those who feared the develop-· ment of conflict in Iran between the super powers during the Second World War. Since, fortunately, such a conflict did not develop some of the Iranians who fled to Herat and other western provinces of Afghanistan returned to Iran and others '"'ettled in these areas, especially in Herat, to become citizens of the Afghan kin~dom. In all fonns of human transmigration it is the magnitude of the people moving that create problems often for the host countries. Therefore:, an in vestigation into the problems of the Afghan refugees in Iran, and the Iranians' attidude toward these refugees was needed for the benefit of those concerned uith the tragedy of Afghanistan and the brutality befalling the Afghan people by the Russians and their puppets in Kabul. The Afghan Refugees--~heir Number and Origins: Today, in Iran the magnitude of the Afghan refugees is unknmm. The refugees themselves are vague in their ansuers to the questions eliciting the number. They often articulate their answer in the following manner: "There are manyn~ "There are a lot of them";: "Afghans are scattered from Tabriz to Tayabad"; ''We are everywhere". -

Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan

February 2002 Vol. 14, No. 2(G) AFGHANISTAN, IRAN, AND PAKISTAN CLOSED DOOR POLICY: Afghan Refugees in Pakistan and Iran “The bombing was so strong and we were so afraid to leave our homes. We were just like little birds in a cage, with all this noise and destruction going on all around us.” Testimony to Human Rights Watch I. MAP OF REFUGEE A ND IDP CAMPS DISCUSSED IN THE REPORT .................................................................................... 3 II. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 III. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 6 To the Government of Iran:....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 To the Government of Pakistan:............................................................................................................................................................... 7 To UNHCR :............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Water Dispute Escalating Between Iran and Afghanistan

Atlantic Council SOUTH ASIA CENTER ISSUE BRIEF Water Dispute Escalating between Iran and Afghanistan AUGUST 2016 FATEMEH AMAN Iran and Afghanistan have no major territorial disputes, unlike Afghanistan and Pakistan or Pakistan and India. However, a festering disagreement over allocation of water from the Helmand River is threatening their relationship as each side suffers from droughts, climate change, and the lack of proper water management. Both countries have continued to build dams and dig wells without environmental surveys, diverted the flow of water, and planted crops not suitable for the changing climate. Without better management and international help, there are likely to be escalating crises. Improving and clarifying existing agreements is also vital. The United States once played a critical role in mediating water disputes between Iran and Afghanistan. It is in the interest of the United States, which is striving to shore up the Afghan government and the region at large, to help resolve disagreements between Iran and Afghanistan over the Helmand and other shared rivers. The Atlantic Council Future Historical context of Iran Initiative aims to Disputes over water between Iran and Afghanistan date to the 1870s galvanize the international when Afghanistan was under British control. A British officer drew community—led by the United States with its global allies the Iran-Afghan border along the main branch of the Helmand River. and partners—to increase the In 1939, the Iranian government of Reza Shah Pahlavi and Mohammad Joint Comprehensive Plan of Zahir Shah’s Afghanistan government signed a treaty on sharing the Action’s chances for success and river’s waters, but the Afghans failed to ratify it. -

Repatriation of Afghan Refugees from Iran: a Shelter Profile Study

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons Robert Stempel College of Public Health & School of Social Work Social Work 2018 Repatriation of Afghan refugees from Iran: a shelter profile study Mitra Naseh Miriam Potocky Paul H. Stuart Sara Pezeshk Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/social_work_fac Part of the Social Work Commons This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Robert Stempel College of Public Health & Social Work at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Social Work by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naseh et al. Journal of International Humanitarian Action (2018) 3:13 Journal of International https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-018-0041-8 Humanitarian Action RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Repatriation of Afghan refugees from Iran: a shelter profile study Mitra Naseh1* , Miriam Potocky1, Paul H. Stuart1 and Sara Pezeshk2 Abstract One in every nine refugees worldwide is from Afghanistan, and Iran is one of main host countries for these refugees. Close to 40 years of hosting Afghan refugees have depleted resources in Iran and resulted in promoting and sometimes forcing repatriation. Repatriation of Afghan refugees from Iran to Afghanistan has been long facilitated by humanitarian organizations with the premise that it will end prolonged displacement. However, lack of minimum standards of living, among other factors such as private covered living area, can make repatriation far from a durable solution. This study aims to highlight the value of access to shelter as a pull factor in ending forced displacement, by comparing Afghan refugees’ housing situation in Iran with returnees’ access to shelter in Afghanistan. -

Afghans in Iran

HUMAN RIGHTS UNWELCOME GUESTS Iran’s Violation of Afghan Refugee and Migrant Rights WATCH Unwelcome Guests Iran’s Violation of Afghan Refugee and Migrant Rights Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0770 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org NOVEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0770 Unwelcome Guests Iran’s Violation of Afghan Refugee and Migrant Rights Map .................................................................................................................................... i Glossary/Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... -

Second-Generation Afghans in Iran: Integration, Identity and Return

Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Case Study Series Second-generation Afghans in Iran: Integration, Identity and Return Mohammad Jalal Abbasi-Shavazi Diana Glazebrook Gholamreza Jamshidiha Hossein Mahmoudian Rasoul Sadeghi April 2008 Funding for this research was provided by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the European Commission (EC) i AREU Case Study Series © 2008 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] or calling +93 799 608548. ii Second-generation Afghans in Iran: Integration, Identity and Return About the Research Team (in alphabetical order) The research team members for the Second-generation study conducted in 2006-7 also carried out the Transnational Networks study in Iran in 2005-6. Both of these studies were commissioned by the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Mohammad Jalal Abbasi-Shavazi is an Associate Professor in the Department of Demography of the University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran, and Adjunct Professor, Australian Demographic and Social Research Institute, Australian National University. Abbasi- Shavazi’s PhD study focused on immigrant fertility in Australia. He has conducted several studies on Iranian fertility transition as well as the Afghan refugees in Iran, and has published extensively on these subjects. He directed the project on Transnational Networks among Afghans in Iran in 2005, and prepared a country report on the situation of International Migrants and Refugees in the Iran in 2007. -

Entrepreneurialism Through Self-Management in Afghan Guest Towns in Iran

Article Entrepreneurialism through Self-Management in Afghan Guest Towns in Iran Jussi S. Jauhiainen 1,2,* and Davood Eyvazlu 3 1 Department of Geography and Geology, University of Turku, FI-20014 Turku, Finland 2 Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, University of Tartu, EE-51014 Tartu, Estonia 3 Sharif Policy Research Institute (Iran Migration Observatory), Sharif University of Technology, 11365-11155 Tehran, Iran; [email protected] * Correspondence: jusaja@utu.fi; Tel.: +358-50-448-12-08 Received: 25 September 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 22 October 2020 Abstract: This article studies the self-management of guest towns (GTs) in Iran and the development of Afghan refugees’ employment and entrepreneurship in these settlements. No earlier research exists on refugee entrepreneurialism in GTs in Iran. The research is based on surveys (546 refugee respondents), interviews (35 refugees) and observations in four GTs in Iran, and interviews (12) with key public authorities related to Afghan refugees in Iran. Of the nearly one million Afghan refugees in Iran, approximately 30,000 reside in 20 GTs, each having up to a few thousand inhabitants. Following a decrease in international support for Afghan refugees and national privatisation policies, the Iranian government decided in 2003 that GTs needed to be self-managed to be financially self-sustainable by their Afghan refugee inhabitants. The motivation and necessity generated by GT self-management led to the increase, diversification, and profit orientation in Afghan refugees’ economic activities in the GTs. The GT refugee councils facilitated internal entrepreneurship fostered externally by state policies, such as the GTs’ obligation to become economically self-sustainable and the provision of tax exemptions and other incentives to GTs. -

UNHCR Iran Operational Update

OPERATIONAL UPDATE - IRAN / November – December 2020 IRAN November – December 2020 OPERATIONAL CONTEXT In December, COVID-19 infections continued to rise, although the rise was slower than previous months, giving cause for cautious optimism. Movement restrictions, closures of non-essential businesses and health protocols continued to be reinforced throughout the country. The Statistical Centre of Iran announced that the inflation rate in 2020 stood at 30.5 percent, rising by 1.5 percent from the previous year. As such, the inflated prices of basic goods continued to affect refugees’ and host communities ability to meet their basic needs. In 2020, according to UNHCR’s Global Appeal for 2021, Iran ranked as the world’s eight-largest refugee-hosting country, as it continued to host 800,000 Afghan and Iraqi refugees. In November, children at risk of statelessmess started receiving Iranian identity documents, as a result of a law passed by the Government of Iran in September 2019, allowing children born to Iranian mothers and non-Iranian fathers to become eligible for the Iranian nationality. POPULATION MOVEMENTS VOLUNTARY REPATRIATION 947 individuals, all Afghans, returned to their country of origin from Iran in 2020, as part of UNHCR’s voluntary repatriation programme. In 2019, a total of 2,009 refugees were voluntarily repatriated. Due to COVID-19, UNHCR is currently only carrying out voluntary repatriations from its Dogharoun Field Unit. RESETTLEMENT In 2020, UNHCR Iran only received resettlement quota for 120 individuals – the lowest since UNHCR started resettlement activity in Iran in 1999. The United Kingdom provided a quota of 100, while Iceland provided a quota of 20. -

Human Rights Violations Under Iran's National Security Laws – June 2020

In the Name of Security Human rights violations under Iran’s national security laws Drewery Dyke © Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Rights Group International June 2020 Cover photo: Military parade in Tehran, September 2008, to commemorate anniversary of This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. Iran-Iraq war. The event coincided The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the publishers and can under with escalating US-Iran tensions. no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. © Behrouz Mehri/AFP via Getty Images This report was edited by Robert Bain and copy-edited by Sophie Richmond. Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is a new initiative to develop ‘civilian-led monitoring’ of violations of international humanitarian law or human rights, to pursue legal and political accountability for those responsible for such violations, and to develop the practice of civilian rights. The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is registered as a charity and a company limited by guarantee under English law; charity no: 1160083, company no: 9069133. Minority Rights Group International MRG is an NGO working to secure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation and understanding between communities. MRG works with over 150 partner organizations in nearly 50 countries. It has consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and observer status with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR). MRG is registered as a charity and a company limited by guarantee under English law; charity no: 282305, company no: 1544957. -

AFGHANISTAN? a Study of Afghans Living in Tehran

Case Study Series RETURN TO AFGHANISTAN? A Study of Afghans Living in Tehran Faculty of Social Sciences University of Tehran Mohammad Jalal Abbasi-Shavazi, Diana Glazebrook, Gholamreza Jamshidiha, Hossein Mahmoudian and Rasoul Sadeghi June 2005 Funding for this research was provided by The European Commission (EC), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Stichting Vluchteling. © 2005 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. All rights reserved. This case study was prepared by independent consultants with no previous involvement in the activities evaluated. The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of AREU. Return to Afghanistan? A Study of Afghans Living in Tehran About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation that conducts and facilitates action-oriented research and learning that informs and influences policy and practice. AREU also actively promotes a culture of research and learning by strengthening analytical capacity in Afghanistan and by creating opportunities for analysis and debate. Fundamental to AREU’s vision is that its work should improve Afghan lives. AREU was established by the assistance community working in Afghanistan and has a board of directors with representation from donors, UN and multilateral organisa- tions agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Current funding for AREU is provided by the European Commission (EC), the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), and the governments of Great Britain, Switzerland and Sweden. Funding for this research was provided by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the EC and Stichting Vluchteling. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit 1 Return to Afghanistan? A Study of Afghans Living in Tehran Foreword Iran is one of the most concentrated areas of Afghan migrants and refugees.