Regent Parrots Feeding on Fruit of the Box Mistletoe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Superb Parrot Conservation Research Plan

Superb Parrot Conservation Research Plan Version 2: 29 July 2020 PLAN DATE PREPARED FOR CWP Renewables Pty Ltd Bango Wind Farm Contact 1: Leanne Cross P. (02) 4013 4640 M. 0416 932 549 E. [email protected] Contact 2: Alana Gordijn P. (02) 6100 2122 M. 0414 934 538 E. [email protected] PREPARED BY Dr Laura Rayner P. (02) 6207 7614 M. 0418 414 487 E. [email protected] on behalf of The National Superb Parrot Recovery Team BACKGROUND The Superb Parrot ................................................................................................................................................................2 PURPOSE Commonwealth compliance .......................................................................................................................................................2 PROJECT OVERVIEW Primary aims of proposed research ...................................................................................................................3 SCOPE OF WORK Objectives and approach of proposed research ...................................................................................................3 PROJECT A Understanding local and regional movements of Superb Parrots ....................................................................................................... 3 PROJECT B Understanding the breeding ecology and conservation status of Superb Parrots .......................................................................... 3 SIGNIFICANCE Alignment of project aims with recovery plan objectives -

Catalogue of Protozoan Parasites Recorded in Australia Peter J. O

1 CATALOGUE OF PROTOZOAN PARASITES RECORDED IN AUSTRALIA PETER J. O’DONOGHUE & ROBERT D. ADLARD O’Donoghue, P.J. & Adlard, R.D. 2000 02 29: Catalogue of protozoan parasites recorded in Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 45(1):1-164. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Published reports of protozoan species from Australian animals have been compiled into a host- parasite checklist, a parasite-host checklist and a cross-referenced bibliography. Protozoa listed include parasites, commensals and symbionts but free-living species have been excluded. Over 590 protozoan species are listed including amoebae, flagellates, ciliates and ‘sporozoa’ (the latter comprising apicomplexans, microsporans, myxozoans, haplosporidians and paramyxeans). Organisms are recorded in association with some 520 hosts including mammals, marsupials, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Information has been abstracted from over 1,270 scientific publications predating 1999 and all records include taxonomic authorities, synonyms, common names, sites of infection within hosts and geographic locations. Protozoa, parasite checklist, host checklist, bibliography, Australia. Peter J. O’Donoghue, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia; Robert D. Adlard, Protozoa Section, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia; 31 January 2000. CONTENTS the literature for reports relevant to contemporary studies. Such problems could be avoided if all previous HOST-PARASITE CHECKLIST 5 records were consolidated into a single database. Most Mammals 5 researchers currently avail themselves of various Reptiles 21 electronic database and abstracting services but none Amphibians 26 include literature published earlier than 1985 and not all Birds 34 journal titles are covered in their databases. Fish 44 Invertebrates 54 Several catalogues of parasites in Australian PARASITE-HOST CHECKLIST 63 hosts have previously been published. -

Psittacid Herpesviruses and Mucosal Papillomas of Birds in Australia Fact Sheet

Psittacid herpesviruses and mucosal papillomas of birds in Australia Fact sheet Introductory statement Psittacid herpesvirus-1 (PsHV-1) has not been reported in wild Australian parrots. Psittacid herpesviruses have been identified in captive green-winged macaws (Ara chloroptera) in Australia. The four genotypes of PsHV-1 are the etiologic agents of Pacheco’s disease (Tomaszewski et al. 2003). Pacheco’s disease is an acute rapidly fatal disease of parrots that has caused significant mortality events in captive parrot collections. Many species of Australian parrot are among those that are susceptible to PsHV-1 infection and disease (Phalen 2006). Subclinical infections result in birds that remain infected for life. These birds are then sources for future outbreaks (Tomaszewski et al. 2006). Parrots subclinically infected with PsHV-1 genotypes 1, 2 and 3 may develop mucosal papillomas (Styles et al. 2004; Styles 2005). Mucosal papillomas have been detected in green-winged macaws imported into Australia (Gallagher and Sullivan 1997; Roe 1997; Vogelnest et al. 2005 ) and they have been confirmed to contain PsHV-1 (Raidal et al. 1998; Vogelnest et al. 2005 ). Although there is no evidence of PsHV-1 in wild Australian parrots (Raidal et al. 1998), the establishment of PsHV-1 in Australia poses a significant risk to captive parrots and a potential risk to wild Australian parrots. Aetiology Family (Herpesviridae), subfamily (Alphaherpesvirinae) genus (Iltovirus). Natural hosts Psittacine birds (parrots) are both the natural host and the most susceptible to disease. Whether infection proceeds to a carrier state, the development of mucosal papillomas, or Pacheco’s disease depends on the genotype of the virus and the species of parrot that it infects (Styles et al. -

Princess Parrot.Pdf

Husbandry Guidelines for Princess Parrots Polytelis alexandrae SALLY FLEW 1 ` Husbandry Guidelines for Princess Parrot Polytelis alexandrae (Aves : Psittacidae) Compiled by: Ms Sally Anne Flew Date of Preparation: 2009-10 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Certificate 3 Captive Animals RUV 30204 Lecturer: Graeme Phipps, Jackie Salkeld, Brad Walker. Husbandry Guidelines for Princess Parrots Polytelis alexandrae SALLY FLEW 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2 TAXONOMY ...................................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2.1 NOMENCLATURE .................................................................. ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2.2 SUBSPECIES .......................................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2.3 RECENT SYNONYMS ............................................................. ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2.4 OTHER COMMON NAMES ..................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 3 NATURAL HISTORY ....................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 3.1 MORPHOMETRICS ................................................................. ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 3.1.1 Mass And Basic Body Measurements ...................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism .................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. -

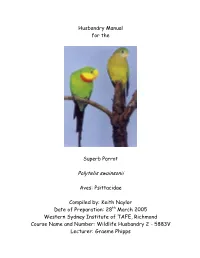

Husbandry Manual for the Superb Parrot

Husbandry Manual for the Superb Parrot Polytelis swainsonii Aves: Psittacidae Compiled by: Keith Naylor Date of Preparation: 28th March 2005 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Course Name and Number: Wildlife Husbandry 2 - 5883V Lecturer: Graeme Phipps Animal Care Studies - Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond This husbandry manual was produced by Keith Naylor at TAFE N.S.W. – Western Sydney Institute, Richmond College, N.S.W. as part of the assessment for completion of the Animal Care Studies Course No. 8128. Keith Naylor 28/3/2005 Version 3 2 Animal Care Studies - Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 7 2 TAXONOMY 8 2.1 Nomenclature 8 2.2 Subspecies 8 2.3 Recent Synonyms 8 2.4 Other Common Names 8 3 NATURAL HISTORY 9 3.1 Morphometrics (Key Measurements and Features) 9 3.1.1 Mass and Basic Body Measurements 9 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism 9 3.1.3 Distinguishing Features 10 3.2 Distribution and Habitat 11 (Breeding, Post Breeding Dispersal and Habitat Use) 3.3 Conservation Status 20 3.4 Diet in the Wild 20 3.5 Longevity 22 3.5.1 In the Wild 22 3.5.2 In Captivity 22 3.5.3 Techniques Used to Determine Age in Adults 22 4 HOUSING REQUIREMENTS 23 4.1 Exhibit/Enclosure Design 23 4.2 Holding Area Design 33 4.3 Spatial Requirements 33 4.4 Position of Enclosures 34 4.5 Weather Protection 34 4.6 Temperature Requirements 34 4.7 Substrate 34 4.8 Nestboxes and/or Bedding Material 36 4.9 Enclosure Furnishings 36 5 GENERAL HUSBANDRY 37 5.1 Hygiene and Cleaning 37 5.2 Record Keeping 40 5.3 Methods of Identification -

Resolving a Phylogenetic Hypothesis for Parrots: Implications from Systematics to Conservation

Emu - Austral Ornithology ISSN: 0158-4197 (Print) 1448-5540 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/temu20 Resolving a phylogenetic hypothesis for parrots: implications from systematics to conservation Kaiya L. Provost, Leo Joseph & Brian Tilston Smith To cite this article: Kaiya L. Provost, Leo Joseph & Brian Tilston Smith (2017): Resolving a phylogenetic hypothesis for parrots: implications from systematics to conservation, Emu - Austral Ornithology To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01584197.2017.1387030 View supplementary material Published online: 01 Nov 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 51 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=temu20 Download by: [73.29.2.54] Date: 13 November 2017, At: 17:13 EMU - AUSTRAL ORNITHOLOGY, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/01584197.2017.1387030 REVIEW ARTICLE Resolving a phylogenetic hypothesis for parrots: implications from systematics to conservation Kaiya L. Provost a,b, Leo Joseph c and Brian Tilston Smithb aRichard Gilder Graduate School, American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA; bDepartment of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA; cAustralian National Wildlife Collection, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, Canberra, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Advances in sequencing technology and phylogenetics have revolutionised avian biology by Received 27 April 2017 providing an evolutionary framework for studying natural groupings. In the parrots Accepted 21 September 2017 (Psittaciformes), DNA-based studies have led to a reclassification of clades, yet substantial gaps KEYWORDS remain in the data gleaned from genetic information. -

Targeted Fauna Assessment.Pdf

APPENDIX H BORR North and Central Section Targeted Fauna Assessment (Biota, 2019) Bunbury Outer Ring Road Northern and Central Section Targeted Fauna Assessment Prepared for GHD December 2019 BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna © Biota Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd 2020 ABN 49 092 687 119 Level 1, 228 Carr Place Leederville Western Australia 6007 Ph: (08) 9328 1900 Fax: (08) 9328 6138 Project No.: 1463 Prepared by: V. Ford, R. Teale J. Keen, J. King Document Quality Checking History Version: Rev A Peer review: S. Ford Director review: M. Maier Format review: S. Schmidt, M. Maier Approved for issue: M. Maier This document has been prepared to the requirements of the client identified on the cover page and no representation is made to any third party. It may be cited for the purposes of scientific research or other fair use, but it may not be reproduced or distributed to any third party by any physical or electronic means without the express permission of the client for whom it was prepared or Biota Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd. This report has been designed for double-sided printing. Hard copies supplied by Biota are printed on recycled paper. Cube:Current:1463 (BORR North Central Re-survey):Documents:1463 Northern and Central Fauna ARI_Rev0.docx 3 BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna 4 Cube:Current:1463 (BORR North Central Re-survey):Documents:1463 Northern and Central Fauna ARI_Rev0.docx BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna Contents 1.0 Executive Summary 9 1.1 Introduction 9 1.2 Methods -

Australian Magpie Crested Bellbird Australian Raven Crested Pigeon

This list of species in Wandoo Woodlands was compiled from various pieces of data for Bob Huston (Nature Conservation Coordinator – Perth Hills District) by Belinda Milne LIST 1 * = Introduced to Western Australia Australian magpie Crested bellbird Australian raven Crested pigeon Barn owl Domestic pigeon* Black-capped sitella Dusky woodswallow Black-eared cuckoo Elegant parrot Black-faced cuckoo shrike Emu Black-faced woodswallow Fan-tailed cuckoo Black-shouldered kite Galah Blue-breasted fairy-wren Golden whistler Boobook owl Grey butcherbird Broad-tailed thornbill Grey currawong Brown falcon Grey fantail Brown goshawk Grey shrike-thrush Brown honeyeater Hooded robin Brown-headed honeyeater Horsfield’s bronze cuckoo Brown quail Jacky winter Bush stone-curlew Laughing kookaburra* Carnaby’s cockatoo Laughing turtledove* Crested shrike-tit Little wattlebird Common bronzewing Long -billed corella Magpie-lark Silvereye Major Mitchell’s cockatoo Singing honeyeater Malleefowl Splendid fairy-wren Mistletoe bird Striated pardalote Nankeen kestrel Stubble quail New Holland honeyeater Tawny-crowned honeyeater Owlet nightjar Tawny frogmouth Pallid cuckoo Tree martin Painted button quail Wedge-tailed eagle Peregrine falcon Weebill Pied butcherbird Western rosella Port Lincoln/ringneck parrot Western spinebill Purple-crowned lorikeet Western thornbill Rainbow bee-eater Western warbler Red-capped parrot Western yellow robin Red-capped robin White-browed babbler List 1 Continued Red-tailed black cockatoo White-browed scrubwren Red wattlebird White-cheeked -

Survival on the Ark: Life-History Trends in Captive Parrots A

Animal Conservation. Print ISSN 1367-9430 Survival on the ark: life-history trends in captive parrots A. M. Young1, E. A. Hobson1, L. Bingaman Lackey2 & T. F. Wright1 1 Department of Biology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM, USA 2 International Species Information System, Eagan, MN, USA Keywords Abstract captive breeding; ISIS; life-history; lifespan; parrot; Psittaciformes. Members of the order Psittaciformes (parrots and cockatoos) are among the most long-lived and endangered avian species. Comprehensive data on lifespan and Correspondence breeding are critical to setting conservation priorities, parameterizing population Anna M. Young, Department of Biology, viability models, and managing captive and wild populations. To meet these needs, MSC 3AF, New Mexico State University, we analyzed 83 212 life-history records of captive birds from the International Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA Species Information System (ISIS) and calculated lifespan and breeding para- Tel: +1 575 646 4863; meters for 260 species of parrots (71% of extant species). Species varied widely in Fax: +1 575 646 5665 lifespan, with larger species generally living longer than smaller ones. The highest Email: [email protected] maximum lifespan recorded was 92 years in Cacatua moluccensis, but only 11 other species had a maximum lifespan over 50 years. Our data indicate that while some Editor: Iain Gordon captive individuals are capable of reaching extraordinary ages, median lifespans Associate Editor: Iain Gordon are generally shorter than widely assumed, albeit with some increase seen in birds presently held in zoos. Species that lived longer and bred later in life tended to be Received 18 January 2011; accepted 13 June more threatened according to IUCN classifications. -

Indian Myna Acridotheres Tristis Rch 2009, the Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries Was Amalgamated with Other

Invasive animal risk assessment Biosecurity Queensland Agriculture Fisheries and Department of Indian myna Acridotheres tristis Anna Markula, Martin Hannan-Jones and Steve Csurhes First published 2009 Updated 2016 rch 2009, the Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries was amalgamated with other © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/3.0/au/deed.en" http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Photo: Guillaume Blanchard. Image from Wikimedia Commons under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 1.0 Licence. I n v a s i v e a n i m a l r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : Indian myna Acridotheres tristis 2 Contents Introduction 4 Name and taxonomy 4 Description 4 Biology 5 Life history 5 Social organisation 5 Diet and feeding behaviour 6 Preferred habitat 6 Predators and dieseases 7 Distribution and abundance overseas 7 Distribution and abundance in Australia 8 Species conservation status 8 Threat to human health and safety 9 History as a pest 9 Potential distribution and impact in Queensland 10 Threatened bird species 11 Threatened mammaly species 11 Non-threatened species 12 Legal status 12 Numerical risk assessment 12 References 13 Appexdix 1 16 I n v a s i v e a n i m a l r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : Indian myna Acridotheres tristis 3 Introduction Name and taxonomy Species: Acridotheres tristis Syn. -

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum

Memoirs OF THE Queensland Museum W Brisbane Volume 45 29 February 2000 PARTl Memoirs OF THE Queensland Museum Brisbane © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, SouthBrisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 0079-8835 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum maybe reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CATALOGUE OF PROTOZOAN PARASITES RECORDED IN AUSTRALIA PETER J. ODONOGHUE & ROBERT D. ADLARD O'Donoghue, P.J. & Adlard, R.D. 2000 02 29: Catalogue ofprotozoan parasites recorded iii -1 Australia. Memoirs ofThe Oiwenslcmd Museum 45( 1 ): I 63. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Published reports ofprotozoan species from Australian animals have been compiled into a host-parasite checklist, a parasite-host checklist and a cross-referenced bibliography. Protozoa listed include parasites, commensals and s\ mbionls but free-living species have been excluded. Over 590 protozoan species are listed including amoebae, flagcllalcs.ciliates and 'sporo/oa" (tlie latter comprising apicomplexans, microsporans, myxozoans, haplo- sporidians and paramyxeaiis). Organisms are recorded in association with some 520 hosts including eulherian mammals, marsupials, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates.