Couverture BABELAO 1 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Cassian and the Creation of Early Monastic Subjectivity

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2019 Exercising Obedience: John Cassian and the Creation of Early Monastic Subjectivity Joshua Daniel Schachterle University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Schachterle, Joshua Daniel, "Exercising Obedience: John Cassian and the Creation of Early Monastic Subjectivity" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1615. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1615 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Exercising Obedience: John Cassian and the Creation of Early Monastic Subjectivity A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology Joint PhD Program In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Joshua Daniel Schachterle June 2019 Advisor: Gregory Robbins PhD © by Joshua Daniel Schachterle All Rights Reserved Author: Joshua Daniel Schachterle Title: Exercising Obedience: John Cassian and the Creation of Early Monastic Subjectivity Advisor: Gregory Robbins PhD Date: June 2019 Abstract John Cassian (360-435 CE) started his monastic career in Bethlehem. He later traveled to the Egyptian desert, living there as a monk, meeting the venerated Desert Fathers, and learning from them for about fifteen years. Much later, he would go to the region of Gaul to help establish a monastery there by writing monastic manuals, the Institutes and the Conferences. -

69 CHAPTER 4 PAUL and PETER: FIRST-CENTURY LETTER WRITERS 1. Paul's Letters and His Co-Authors Among Thirteen Traditional Paul

CHAPTER 4 PAUL AND PETER: FIRST-CENTURY LETTER WRITERS 1. Paul’s Letters and His Co-authors Among thirteen traditional Pauline letters, including the disputed letters – Ephesians, Colossians, 2 Thessalonians, and the Pastoral Epistles – Paul’s colleagues are shown as co-senders in his eight letters. Figure 3. Cosenders in Paul’s Epistles 1 Corinthians Sosthenes 2 Corinthians Timothy Galatians All the brothers with Paul Philippians Timothy Colossians Timothy 1 Thessalonians Silvanus and Timothy 2 Thessalonians Silvanus and Timothy Philemon Timothy The issue that the co-senders in the Pauline letters naturally signify co-authors certainly seems to deserve investigation; however, it has been ignored by scholars. On this point, Prior criticizes Doty and White for not differentiating between the associates who greet at the closing of the letter and the colleagues who are named in 69 the letter address, and for not even stating the appearance of “co-senders” including confounding them with amanuenses, respectively. 1 Similarly, Murphy-O’Connor properly points out that it is simply habitual not to distinguish those correspondences that Paul composed with co-senders from those correspondences he wrote solely.2 According to Prior and Richards, the practice of co-authorship in the ancient world is exceedingly unusual. Among the extant papyri, Prior and Richards found merely fifteen and six letters, respectively.3 This minute ratio clearly shows that Paul’s naming of different individuals with the author at the beginning of the correspondence was not an insignificant custom.4 It is generally suggested that Paul’s naming his associates in the address of his letters is “largely a matter of courtesy.”5 However, this traditional and customary view is criticized by Richards on at least two points. -

“Make This the Place Where Your Glory Dwells”: Origins

“MAKE THIS THE PLACE WHERE YOUR GLORY DWELLS”: ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF THE BYZANTINE RITE FOR THE CONSECRATION OF A CHURCH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Vitalijs Permjakovs ____________________________ Maxwell E. Johnson, Director Graduate Program in Theology Notre Dame, Indiana April 2012 © Copyright 2012 Vitalijs Permjakovs All rights reserved “MAKE THIS THE PLACE WHERE YOUR GLORY DWELLS”: ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF THE BYZANTINE RITE FOR THE CONSECRATION OF A CHURCH Abstract by Vitalijs Permjakovs The Byzantine ritual for dedication of churches, as it appears in its earliest complete text, the eighth-century euchologion Barberini gr. 336, as well as in the textus receptus of the rite, represents a unique collection of scriptural and euchological texts, together with the ritual actions, intended to set aside the physical space of a public building for liturgical use. The Byzantine rite, in its shape already largely present in Barberini gr. 336, actually comprises three major liturgical elements: 1) consecration of the altar; 2) consecration of the church building; 3) deposition of relics. Our earliest Byzantine liturgical text clearly conceives of the consecration of the altar and the deposition of the relics/“renovation” (encaenia) as two distinct rites, not merely elements of a single ritual. This feature of the Barberini text raises an important question, namely, which of these major elements did in fact constitute the act of dedicating/ consecrating the church, and what role did the deposition of relics have in the ceremonies of dedication in the early period of Byzantine liturgical history, considering that the deposition of relics Vitalijs Permjakovs became a mandatory element of the dedication rite only after the provisions to that effect were made at the Second council of Nicaea in 787 CE. -

Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for The

THE SPIRITUAL ANTHROPOLOGY OF JOHN CASSLAN JINHAKIM Submitted in accordancewith the requirements for the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Department of Theology and Religious Studies October2OO2 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Abstract THE SPIRITUAL ANTHROPOLOGY OF JOHN CASSIAN PHD THESIS SUBMITTED BY J114HAKIM This thesis is an investigation into the spiritual anthropology of John Cassian, who composed two monastic works, the Institutes and the Conferences.Although Cassian transmits the teachings of the Egyptian desert fathers living in the later fourth century, many polemical mind-sets, from his Latin contemporaries to modem critics, have not been able simply to accept his delivery with a spirit of respect and support. In his texts, the doctrine of free will and grace has been judged to be Semi-Pelagian through the viewpoint of Augustinian orthodoxy. Moreover, since Salvatore Marsili's comparative study in the 1930s, it has been accepted that Cassian's ascetic theology depended heavily on the writings of Evagrius Ponticus. Thus, the authenticity of his texts has been obscured for over fifteen hundred years in the West. Consequently, they have been regarded as second-class materials in the primitive desert monastic literature. This thesis re-examines the above settled convictions, and attempts to defend Cassian'srepeated statements that he wrote what he had seen and heard in the desert. -

Scribal Habits in Selected New Testament Manuscripts, Including Those with Surviving Exemplars

SCRIBAL HABITS IN SELECTED NEW TESTAMENT MANUSCRIPTS, INCLUDING THOSE WITH SURVIVING EXEMPLARS by ALAN TAYLOR FARNES A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Institute for Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing Department of Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham April 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract In the first chapter of this work, I provide an introduction to the current discussion of scribal habits. In Chapter Two, I discuss Abschriften—or manuscripts with extant known exemplars—, their history in textual criticism, and how they can be used to elucidate the discussion of scribal habits. I also present a methodology for determining if a manuscript is an Abschrift. In Chapter Three, I analyze P127, which is not an Abschrift, in order that we may become familiar with determining scribal habits by singular readings. Chapters Four through Six present the scribal habits of selected proposed manuscript pairs: 0319 and 0320 as direct copies of 06 (with their Latin counterparts VL76 and VL83 as direct copies of VL75), 205 as a direct copy of 2886, and 821 as a direct copy of 0141. -

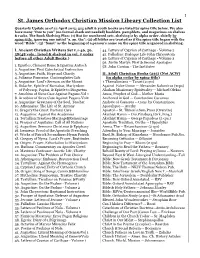

St. James Orthodox Christian Mission Library Collection List

1 St. James Orthodox Christian Mission Library Collection List Quarterly Update as of 22 April 2015; 325 adult & youth books are listed by spine title below. We also have many “free to you” (no formal check out needed) booklets, pamphlets, and magazines on shelves & racks. The Book Shelving Plan: (1) But for numbered sets, shelving is by alpha order, chiefly by spine-title, ignoring any initial “a, an, the”; (2) all bibles are treated as if the spine title began with the word “Bible”; (3) “Saint” as the beginning of a person’s name on the spine title is ignored in shelving. I. Ancient Christian Writers Set v.1-46, 56, 44. Letters of Cyprian of Carthage - Volume 2 58(48 vols.; listed & shelved in vol. # order 45. Palladius: Dialogue Life John Chrysostom before all other Adult Books.) 46. Letters of Cyprian of Carthage - Volume 3 56. Justin Martyr: First & Second Apologies 1. Epistles, Clement Rome & Ignatius Antioch 58. John Cassian - The Institutes 2. Augustine: First Catechetical Instruction 3. Augustine: Faith, Hope and Charity II. Adult Christian Books (235) (Not ACW) 4. Julianus Pomerius: Contemplative Life (in alpha order by spine title) 5. Augustine: Lord's Sermon on the Mount 1 Thessalonians -- Tarazi (2 cps) 6. Didache, Epistle of Barnabas, Martyrdom Against False Union -- Alexander Kalomiros (2cps) of Polycarp, Papias, & Epistle to Diognetus Alaskan Missionary Spirituality -- Michael Oleksa 7. Arnobius of Sicca:Case Against Pagans-Vol 1 Amos, Prophet of God -- Mother Maria 8. Arnobius of Sicca:Case Against Pagans-Vol2 Anchored in God -- Constantine Cavarnos 9. Augustine: Greatness of the Soul, Teacher Andrew of Caesarea -- trans. -

Bulgakov Handbook

Cheese Fare Week This week received its name because the holy Church, gradually leading believers into the ascetical deeds (podvig) of the holy Lent, with the approach of Cheese Fare Week puts them on the last step of the preparatory abstinence by prohibiting the partaking of meat and permitting the partaking of cheese and eggs, in order to accustom them to avoid pleasant foods and without grief to enter the fast. In popular speech it is called butter week or shrove tide (maslianitsi) week. The holy Church calls it "the light before the journey of abstinence" and "the beginning of tenderness and repentance". Such a meaning of Cheese Fare Week is detailed and explained in its Divine services. Especially the canons and the stichera of these Divine services contain the praise of Lent and the representation of its saving fruits. During this week the Divine services enter into a closer relation with the Divine services of the Holy Forty Day Fast as the time of the latter approaches. Thus, the holy Church, highly honoring the time of the Holy Forty Day Fast as a sacred time for cleansing and immensely important for the Christian, with truly wise foresight and by sequence directs everything to lead us to "the most precious days of the Holy Forty Day Fast", cleansing us beforehand to prepare us for the fast and repentance. In the sacred hymns for this week the Holy Church as mother appeals to all: "Let us now approach this week of cleansing before the all honorable sacred fast now at hand, illumining bodies and souls"; "Therefore let us hasten -

THE COLLECTION of PAUL's LETTERS Return to Religion-Online the Oldest Extant Editions of the Letters of Paul by David Trobisch

THE COLLECTION OF PAUL'S LETTERS return to religion-online The Oldest Extant Editions of the Letters of Paul by David Trobisch David Trobisch was born in Cameroon (West Africa) as the son of missionaries. The family then moved to Austria. He studied theology at the Universitiesof Tuebingen and Heidelberg in Germany. He taught at the University of Heidelberg for ten years before accepting teaching positions at South West Missouri State University, Yale Divinity School and Bangor Theological Seminary. For a more detailed curriculum vitae and a list of publications see http://www.bts.edu/faculty/trobisch.htm The Oldest Extant Editions of the Letters of Paul (David Trobisch, 1999) David Trobisch was born in Cameroon (West Africa) as the son of missionaries. The family then moved to Austria. He studied theology at the Universitiesof Tuebingen and Heidelberg in Germany. He taught at the University of Heidelberg for ten years before accepting teaching positions at South West Missouri State University, Yale Divinity School and Bangor Theological Seminary. For a more detailed curriculum vitae and a list of publications see http://www.bts.edu/faculty/trobisch.htm Table of Contents Introduction* Different Editions* Huge Number of Manuscripts* Grouping Manuscripts* The Authorized Byzantine Version* Fragmentary Manuscripts* The Manuscripts* Introduction* Notation of Manuscripts* The Oldest Manuscripts of the Christian Bible* Codex Alexandrinus (A 02)* Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (C 04)* Codex Sinaiticus (À 01)* Codex Vaticanus (B 03)* Number and Sequence -

Doctrinal Controversy and the Church Economy of Post-Chalcedon Palestine

Doctrinal Controversy and the Church Economy of Post-Chalcedon Palestine Daniel Paul Neary Faculty of History University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corpus Christi College September 2017 ii CONTENTS Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations iv Introduction 6 Chapter 1 – Reappraising the Rebellion against Juvenal of Jerusalem: Aristocratic Patronage and ‘Anti-Chalcedonian’ Violence, 451-453 CE 22 Chapter 2 – Contesting the ‘Church of the Bishops’: Controversy after Chalcedon, 453-518 CE 50 Chapter 3 - Church Economy and Factional Formation 69 Chapter 4 – Jerusalem under Justinian 100 Chapter 5 – Controversy and Calamity: Debating Doctrine on the Eve of the Islamic Conquests 134 Conclusion 165 Appendix A – Donors, Patrons and Monastic Proprietors in the Lives of Cyril of Scythopolis 171 Appendix B – Palestinian Delegates and Spectators at the Synod of Constantinople (536 CE) 177 Bibliography 179 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC UK) and the Faculty of History of the University of Cambridge for funding this research. I will always be grateful to my supervisor, Peter Sarris, for guiding this project to completion over the past four years. My interest in the history of the Eastern Roman Empire was first encouraged by two inspirational teachers, John and Nicola Aldred. Since arriving in Oxford as an undergraduate in 2008, I have encountered many more, among them Neil McLynn, Mark Whittow, Bryan Ward-Perkins, Phil Booth, Mary Whitby, Ida Toth, Neil Wright, Esther-Miriam Wagner and Nineb Lamassu. Mark had been due to act as external examiner of this thesis. His tragic and premature death last December left us, his former students, profoundly saddened. -

Download Thesis

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE PRACTICES OF THE MYSTICS SADHU SUNDAR SINGH AND THE DESERT FATHERS AND THE IMPLICATIONS OF APPROPRIATING CHRISTIAN MYSTIC PRACTICES IN THE CHURCH TODAY by CLAYTON AARON PARKS A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY IN PRACTICAL THEOLOGY SOUTH AFRICAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY JULY 2015 SUPERVISOR: DR. SIGA ARLES CO-SUPERVISOR: DR. NOEL BEAUMONT WOODBRIDGE The opinions expressed in this dissertation do not necessarily reflect the views of the South African Theological Seminary. DECLARATION I hereby acknowledge that the work contained in this dissertation is my own original work and has not previously in its entirety or in part been submitted to any academic institution for degree purposes. ___________________________ Clayton Parks 09/01/2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are for too many to thank for their encouragement, support and prayer during the completion of this dissertation. I am particularly indebted to the following individuals: To my wonderful wife, Hannah, for her love, patience and gentle nudging throughout the research process. To my Father-Confessor, the Archpriest Fr. Stephen Salaris, for his encouragement on all the days that I wanted to give up. To Dr. Siga Arles and Dr. Noel Woodbridge, my promoters, for all of their insights and quick responses. To the Postgraduate School of South African Theological Seminary for allowing me do research at the doctoral level. To All-Saints of North America Antiochian Orthodox Church for letting me miss the occasional service to continue my research. To my maternal Grandmother, Margaret for providing me with the “seed of faith” from a small age. -

![UNF: the Byzantine Saint: a Bibliography [Halsall]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6347/unf-the-byzantine-saint-a-bibliography-halsall-7766347.webp)

UNF: the Byzantine Saint: a Bibliography [Halsall]

Paul Halsall The Byzantine Saint: A Bibliography (2005) Introduction This thematic bibliography should be read in conjunction with Alice-Mary Talbot's Survey of Translations of Byzantine Saints' Lives [at Dumbarton Oaks], which lists all available Byzantine saint's lives translated into any modern western language. This bibliography was compiled for my dissertation and for a class I taught on the history of sainthood in 2005. It is therefore now out of date but may still prove of some interest. Contents I: What is a Saint? o Sainthood: General o Hagiography: General o Canonization: General o Byzantine Sainthood: General o Byzantine Hagiography o Byzantine Sainthood: Saint-Making/Canonization o Locating Information on Saints o Internet Bibliographies II: Biography III: The Novel IV: The Pagan Holy Man V: Martyrs: Pagan and Christian Sources VI: The Life of Anthony VII: Early Monasticism I: Egypt and Pachomius VIII: Early Monasticism II: Palestine IX: Early Monasticism III: Syria X: The Christian Holy Man in Society: Ascetics XI: The Christian Holy Man in Society II: Bishops XII: Women Saints I: The Early Church XIII: Women Saints II: The Byzantine Period XIV: Thaumaturgy (Wonder-Working), Miracles and Healing XV: From Hagiography to Legend XVI: The Metaphrastic Effort XVII: Middle Byzantine Sainthood XVIII: Later Byzantine Sainthood XIX: Byzantine Monasticism and Sainthood XX: Post-Byzantine Greek Saints XXI: The Theotokos XXII: Saints in Art XXIII: Saints in Liturgy XXIV: Slavic Saints XXV: Major Collections I: What is a Saint? Sainthood: General Brown, Peter R. L. The Cult of the Saints. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1981. [Cf. Averil. -

ZALESKI-DISSERTATION-2019.Pdf (1.436Mb)

Christianity, Islam, and the Religious Culture of Late Antiquity: A Study of Asceticism in Iraq and Northern Mesopotamia The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Zaleski, John. 2019. Christianity, Islam, and the Religious Culture of Late Antiquity: A Study of Asceticism in Iraq and Northern Mesopotamia. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42106922 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Christianity, Islam, and the Religious Culture of Late Antiquity: A Study of Asceticism in Iraq and Northern Mesopotamia A dissertation presented by John Zaleski to The Committee on the Study of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of The Study of Religion Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2019 © 2019 John Zaleski All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Charles M. Stang John Zaleski Christianity, Islam, and the Religious Culture of Late Antiquity: A Study of Asceticism in Iraq and Northern Mesopotamia Abstract This dissertation examines the development of Christian and Islamic writing on asceticism, especially fasting and celibacy, in Iraq and northern Mesopotamia during the formative period of Islam. I show that both Christians and Muslims created ascetic traditions specific to their communities, by reinterpreting the significance of disciplines they held in common and by responding to the practices and ideals of rival confessions.