I N T R O D U C T I O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LUCIS Annual Report 2016 LUCIS Annual Report 2016 Table of Contents | 1

LUCIS Annual Report 2016 LUCIS Annual Report 2016 Table of contents | 1 LUCIS Table of contents Annual Report 2016 List of abbreviations 3 About the Leiden University Centre 4 for the Study of Islam and Society (LUCIS) Introduction by the director 6 Text Annemarie van Sandwijk 1 Sharing Leiden’s knowledge: 8 & Petra Sijpesteijn visibility and outreach Visiting address 1.1 International cooperation: academic activities 12 Witte Singel 25 1.1.1 What’s New?! lecture series 12 Matthias de Vrieshof 4 1.1.2 Academic conferences 12 room 1.06b 1.1.3 Visiting fellowships 13 2311 BZ Leiden 1.1.4 Visiting scholars 14 1.1.5 Annual lecture and annual conference 14 Postal address 1.1.6 Cooperation with Indonesia 15 P.O. Box 9515 1.2 Opening up the academy: public engagement 16 2300 RA Leiden 1.2.1 Current events panel discussions 16 1.2.2 Journalist fellow 16 Telephone 1.2.3 Cultural activities 17 +31 (0)71 527 2628 1.2.4 Cooperation with Leiden museums 18 1.2.5 Cooperation with the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs 19 Email 1.2.6 Leiden-Aramco sponsorship programme 20 [email protected] 1.2.7 Media exposure and Leiden Islam Blog 23 Website 2 Islam and society expertise centre: 24 www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/humanities/centre-for-the-study-of-islam-and-society organisation, internal cohesion and cooperation Leiden Islam Blog 2.1 Organisation 24 www.leiden-islamblog.nl 2.2 LUCIS network of affiliated researchers 26 2.3 Engaging the LUCIS community: annual members’ 26 meeting & network lunches 2.4 Educational programmes 27 2.5 Cooperation with -

The Republic of the Gambia's Combined Report on The

THE REPUBLIC OF THE GAMBIA’S COMBINED REPORT ON THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON HUMAN & PEOPLES’ RIGHTS & INITIAL REPORT ON THE PROTOCOL TO THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN IN AFRICA THE REPUBLIC OF THE GAMBIA COMBINED REPORT ON THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS FOR THE PERIOD 1994 AND 2018. AND INITIAL REPORT UNDER THE PROTOCOL TO THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN IN AFRICA August 2018 1 THE REPUBLIC OF THE GAMBIA’S COMBINED REPORT ON THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON HUMAN & PEOPLES’ RIGHTS & INITIAL REPORT ON THE PROTOCOL TO THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN IN AFRICA PREFACE The Republic of The Gambia is committed to the progressive realization of the rights and freedoms of all persons as well as the duties enshrined in the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights through the creation of appropriate policy, legislative, judicial, administrative and budgetary measures. It is against this background that this Combined Periodic Report seeks to highlight the measures adopted in the implementation of the rights enshrined in the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) since 1994, identify the progress made as well as the constraints encountered. During the period under review (1994-2018), The Republic of The Gambia has had to contend with a very checkered history in the bid to fulfill its obligation to promote and protect human rights. Admittedly, numerous challenges had to be overcome in the effective realization of the promotion and protection of these rights. The Ministry of Justice takes this opportunity to express its appreciation to the distinguished Commissioners of the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights and hope that the distinguished experts will appreciate the progress made so far, the determinations being made to overcome the highlighted challenges and continue to support The Gambia’s obligation to sustain the promotion and protection of human and peoples’ rights in the overall interest of all Gambians. -

Faith-Inspired Organizations and Global Development Policy a Background Review “Mapping” Social and Economic Development Work

BERKLEY CENTER for RELIGION, PEACE & WORLD AFFAIRS GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY 2009 | Faith-Inspired Organizations and Global Development Policy A Background Review “Mapping” Social and Economic Development Work in Europe and Africa BERKLEY CENTER REPORTS A project of the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs and the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University Supported by the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs Luce/SFS Program on Religion and International Affairs From 2006–08, the Berkley Center and the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service (SFS) col- laborated in the implementation of a generous grant from the Henry Luce Foundation’s Initiative on Religion and International Affairs. The Luce/SFS Program on Religion and International Affairs convenes symposia and seminars that bring together scholars and policy experts around emergent issues. The program is organized around two main themes: the religious sources of foreign policy in the US and around the world, and the nexus between religion and global development. Topics covered in 2007–08 included the HIV/AIDS crisis, faith-inspired organizations in the Muslim world, gender and development, religious freedom and US foreign policy, and the intersection of religion, migration, and foreign policy. The Berkley Center The Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs, created within the Office of the President in March 2006, is part of a university-wide effort to build knowledge about religion’s role in world affairs and promote interreligious understanding in the service of peace. The Center explores the inter- section of religion with contemporary global challenges. -

Abdou Jammeh

Acceptability of Voluntary Counselling and Testing For HIV among Pregnant Women in Western Health Division, the Gambia Thesis submitted by: ABDOU JAMMEH As partial fulfilment for the award of the Master of Philosophy Degree (MPhil) in International Community Health Supervisor: PROFESSOR JOHANNE SUNDBY University of Oslo, Norway Faculty of medicine Department of General Practice and Community Medicine Section for International Health MAY 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……….............................................................................................................6 DEDICATION…….............................................................................................................8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT...................................................................................................9 ACRONYMS…….............................................................................................................10 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION.................................................................................. 12 1.1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................12 1.2. PROBLEM STATEMENT.....................................................................................13 1.3. PROFILE OF THE GAMBIA ................................................................................14 1.3.1. Geography........................................................................................................14 1.3.2. Population and Demographic Characteristics..................................................15 -

Anglican Stagnation and Growth in West Africa: the Case of St

Anglican Stagnation and Growth in West Africa: The Case of St. Paul's Church, Fajara, The Gambia. By Christine Elizabeth Curley A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the History Department of the Toronto School of Theology. In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Theology Masters awarded by Wycliffe College and the University of Toronto Copyright Christine E. Curley Anglican Stagnation and Growth in West Africa: The Case of St. Paul's Church, Fajara, The Gambia Christine Elizabeth Curley Theology Masters Wycliffe College 2012 Abstract This paper investigates the history of the Anglican Church in The Gambia, and uses one church, St. Paul‟s, Fajara, as a case study to understand the growth of the Church in the country. This paper evaluates the Anglican leadership in the mid-twentieth century to understand why the growth in the Anglican Church has been so small. To understand the stagnant growth, this paper also explores the Islamic and British backgrounds in the country, as well as some of the evangelistic techniques used by the Anglicans, as well as critiquing leaders in the 1970s and 1980s at St. Paul‟s, Fajara. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Timeline of Pertinent Events ii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: Background of The Gambia 17 Chapter Three: The Anglican Church in The Gambia 32 Chapter Four: Leadership in the Church 48 Chapter Five: Two Case Studies on Leadership 58 Chapter Six: Conclusion 72 Bibliography 76 iii Timeline of pertinent events 11th century: Arabic Islamic Traders make inroads to The Gambia 1855: Anglican Diocese of the West Indies send their first missionaries to The Gambia: James Leacock (A white priest from Barbados) and John Duport (a black ordinand from St. -

2020 Daily Prayer Guide for All Africa People Groups & All LR-Upgs = Least-Reached

2020 Daily Prayer Guide for all Africa People Groups & Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups (LR-UPGs) Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] 2020 Daily Prayer Guide for all Africa People Groups & all LR-UPGs = Least-Reached--Unreached People Groups. All 48 Africa countries & 8 islands & People Groups & LR-UPG are included. LR-UPG defin: less than 2% Evangelical & less than 5% total Christian Frontier definition = FR = 0.1% Christian or less AFRICA SUMMARY: 3,702 total Africa People Groups; 957 total Africa Least-Reached--Unreached People Groups. Downloaded in October 2019 from www.joshuaproject.net * * * Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country shaded = LR-UPG; white-not shaded = not LR-UPG * * * "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" * * * Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! * * * Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. 3:9,15! * In the Great Commissions Jesus commanded us to reach all peoples in the world, Matt. -

Dick's Creek and Its Southerly Tributary That Parallels Oakdale and Merritt Street for About 2.5 Kilometers

Dick’s Creek Richard Pierpoint “Captain Dick” Courageous Leader, Soldier, Hero To the West of Merritt Street, St.Catharines running along side present day Oakdale Avenue within Canal Valley, is Dick’s Creek. Its waterway tells a discordant series of tales that informs that which we see today on Merritt Street. The first and second Welland canals followed Dick’s Creek as they left the boundary of St. Catharines (as it was in 1829 to 1915) and travelled south toward the town of Merritton and the Niagara Escarpment. The First Welland Canal finished in 1829 and used for fifteen years, and the Second Welland Canal finished in 1845 and used until 1915 both follow the main branch of Dick's Creek and its southerly tributary that parallels Oakdale and Merritt Street for about 2.5 kilometers. Dick’s Creek was named after respected, well-liked, Richard “Captain Dick” Pierpoint, who in his life- time was captured by or sold by local slave traders to an America bound British slave ship at 16, escaped American slavery by joining the Loyalist militia in 1780 at 36, acquired in recognition of his brave service a large land grant in 1791 encompassing Dick’s Creek at 47, voluntarily fought in the war of 1812 on behalf of Upper Canada against the Americans as a member of the Coloured Militia he co-founded at 68, received and fulfilled the harsh conditions of acquiring a further land grant in Fergus at the age of 82, and then returned to the area of Dick’s Creek now actively used as part of the Welland Canal where he lived nobly until his death in 1838 at the distinguished age of 94. -

The Wolof of Saloum: Social Structure and Rural Development in Senegal Stellingen

The Wolof of Saloum: social structure and rural development in Senegal Stellingen 1. Ein van de voorwaarden voor succesvolle toepassing van ossetrekkracht in de landbouw is een passende bedrijfsgrootte. In vele samenlevingen in West-Afrika wordt aan deze voor- waarde niet voldaan, omdat de leden van de huishoudgroep niet gezamenlijk, maar afzonder- lijk een bedrijf beheren. Dit proefschrift. 2. De conclusie dat in niet-westerse gebieden de positie van de vrouw verslechtert door opname in de marktecanomie en modernisering van de landbouw, is niet van toepassing op de Wolof-samenleving. Door de verbouw van handelsgewassen werd haar rol in de landbouw be- langrijker en nam haar inkomen toe. De recente toepassing van dierlijke trekkracht ver- lichtte haar taak op haar eigen veld. Postel-Coster, E. & J. Schrijvers, 1976. Vrouwen op weg; ontwikkeling naar emanci- patie. Van Gorcum, Assen. Dit proefschrift. 3. Moore verklaart de deelname aan werkgroepen met een maaltijd als beloning ('festive labour') mede uit de afhankelijkheid van de deelnemers ten opzichte van de begunstigde. Hierbij wordt over het hoofd gezien dat het voorkomt dat slechts een persoon deelneemt vanwege zijn afhankelijkheid van de begunstigde en dat deze persoon de overige deelnemers rekruteert volgens de regels van reciprociteit. Moore, M.P., 1975. Co-operative labour in peasant agriculture. Journal of Peasant Studies 2(3): 270-291. Dit proefschrift. 4. De gebruikelijke definitie van een marabout als zijnde een heilige en religieus leider met erg veel invloed is niet van toepassing op de Wolof, omdat hier vele marabouts slechts lokale bekendheid genieten. Dit proefschrift. 5. Er wordt vaak geen rekening gehouden met het feit dat de materiele positie van de kleine boer in ontwikkelingslanden niet alleen bepaald wordt door zijn activiteit als pro- ducent, maar tevens door zijn activiteit als handelaar. -

Traditional Values and Local Community in the Formal Educational System in Senegal: a Year As a High School Teacher in Thies

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses July 2020 TRADITIONAL VALUES AND LOCAL COMMUNITY IN THE FORMAL EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM IN SENEGAL: A YEAR AS A HIGH SCHOOL TEACHER IN THIES Maguette Diame University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Indigenous Education Commons, International and Comparative Education Commons, and the Language and Literacy Education Commons Recommended Citation Diame, Maguette, "TRADITIONAL VALUES AND LOCAL COMMUNITY IN THE FORMAL EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM IN SENEGAL: A YEAR AS A HIGH SCHOOL TEACHER IN THIES" (2020). Doctoral Dissertations. 1909. https://doi.org/10.7275/prnt-tq72 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1909 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRADITIONAL VALUES AND LOCAL COMMUNITY IN THE FORMAL EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM IN SENEGAL: A YEAR AS A HIGH SCHOOL TEACHER IN THIES A Dissertation Presented by MAGUETTE DIAME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2020 College of Education Department of Educational Policy, Research, and Administration © Copyright -

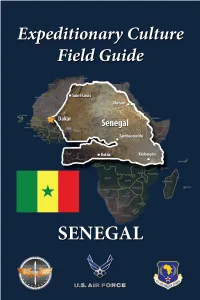

ECFG-Senegal-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo a courtesy of the United Nations). The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” ECFG the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Senegal, focusing on unique cultural Senegal features of Senegalese society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

GUIDE of SÉDHIOU Some Tips to Better Know This City of Senegal

GUIDE OF SÉDHIOU Some tips to better know this city of Senegal INDEX INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 3 GEOGRAPHY ................................................................................... 5 LANGUAGES ..................................................................................12 ENVIRONMENT ..............................................................................16 HEALTH..........................................................................................21 EDUCATION ...................................................................................34 GREETINGS ....................................................................................41 ON THE STREETS OF SEDHIOU ........................................................48 SENEGALESE TIME .........................................................................53 THE SENEGALESE FAMILY ...............................................................56 RELIGION AND TRADITIONAL BELIEFS ............................................60 THE POLYGAMY .............................................................................68 FOOD AND DRINKS ........................................................................71 MUSIC AND DANCING ....................................................................74 ART AND GAMES ...........................................................................78 CLOTHES AND HAIRSTYLES .............................................................82 JOBS ..............................................................................................87 -

Wolof and Wolofisation: Statehood, Colonial Rule, and Identification in Senegal

chapter 3 Wolof and Wolofisation: Statehood, Colonial Rule, and Identification in Senegal Unwelcome Identifications: Colonial Conquest, Independence, and the Uneasiness with Ethnic Sentiment in Contemporary Senegal The ethnic friction which characterises classic interpretations of African states is remarkably absent in Senegalese society. Senegal is often presented as a soci- ety dominated by Wolof-speakers, particularly in the urban agglomeration of Dakar, which has assimilated large groups of immigrants both socially and lin- guistically.1 This has increasingly led scholars to define Senegal as a predomi- nantly ‘Wolof society’, whose language is spreading widely (which is sometimes seen as being linked to Murid Islam as well). The Wolof language has migrated from the region of the capital and other urban communities, such as Saint- Louis, Tivaouane, Thiès, Diourbel, and Kaolack, into the southern coastal belt towards the Gambian border. This has strongly influenced the interpretation of the history of what is present-day Senegal. Pre-colonial states are therefore often described as ‘Wolof states’; their ruling dynasties – if there were any – are defined as ‘Wolof’. The Wolof nature of Senegal’s political structures is not seri- ously in question.2 As Senegambia is located on the early modern sea routes to India and the slave ports of the so-called Guinea Coast, information on its inhabitants was available to Europeans from an early period. Such information was also pro- vided by Eurafricans, who were most strongly present in Casamance and the Cacheu-Bissau area.3 Moreover, European officials managed commercial fac- tories on Senegalese land for centuries, starting as early as the sixteenth cen- tury, although their interest was often focused more on the acquisition of slaves and less on the concrete political realities in the hinterland.