Rp119 Cover.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozambique, [email protected]

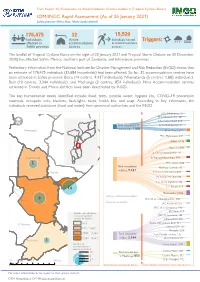

Flash Report 15 | Evacuations to Accommodation Centres Update 2 (Tropical Cyclone Eloise) IOM/INGC Rapid Assessment (As of 25 January 2021) Sofala province (Beira, Buzi, Nhamatanda district) 176,475 32 15,520 Individuals Active Individuals hosted Triggers: in accommodations aected in accommodation Sofala province centres centres The landfall of Tropical Cyclone Eloise on the night of 23 January 2021 and Tropical Storm Chalane on 30 December 2020) has aected Sofala, Manica, southern part of Zambezia, and Inhambane provinces. Preliminary information from the National Institute for Disaster Management and Risk Reduction (INGD) shows that an estimate of 176,475 individuals (35,684 households) had been aected. So far, 32 accommodation centres have been activated in Sofala province: Beira (14 centres, 9,437 individuals), Nhamatanda (5 centres, 1,885 individuals), Buzi (10 centres, 3,344 individuals), and Machanga (3 centres, 854 individuals). Nine Accommodation centres activated in Dondo and Muasa districts have been deactivated by INGD. The top humanitarian needs identied include: food, tents, potable water, hygiene kits, COVID-19 prevention materials, mosquito nets, blankets, ash-lights, tarps, health kits, and soap. According to key informants, the individuals received assistance (food and water) from provincial authorities and the INGD. EPC- Nhampoca: 27 Maringue EPC Nhamphama: 107 EPC Felipe Nyusi: 418 Total evacuations in EPC Nhatiquiriqui: 74 Cheringoma Nhamatanda: Gorongosa 1,885 ES de Tica: 1,259 EPC- Matadouro: 493 IFAPA: 1,138 Muavi 1: 1,011 Muanza E. Comunitaria SEMO: 170 Nhamatanda E. Especial Macurungo: 990 5 EPC- Chota: 600 Total evacuations Munhava Central: 315 in Beira: 9,437 Dondo E S Sansao Mutemba: 428 ES Samora Machel: 814 E. -

Breaking Into the Smallholder Seed Market

BREAKING LESSONS FROM THE MOZAMBIQUE SMALLHOLDER INTO THE EFFECTIVE EXTENSION DRIVEN SMALLHOLDER SUCCESS (SEEDS) PROJECT SEED MARKET Pippy Gardner © 2017 NCBA CLUSA NCBA CLUSA 1775 Eye Street, N.W. Suite 800 Washington, D.C. 20006 SMALLHOLDER EFFECTIVE EXTENSION DRIVEN SUCCESS PROJECT 2017 WHITE PAPER LESSONS LEARNED FROM BREAKING INTO THE MOZAMBIQUE SEEDS THE SMALLHOLDER PROJECT SEED MARKET DECEMBER 2017 Table of Contents 2 Executive Summary 6 Introduction 7 The Seeds Industry in Mozambique 8 Background to the SEEDS Project and Partners 9 Rural Agrodealer Models and Mozambique 11 Activities Implemented and Main Findings/ Reccomendations 22 Seeds Sales 30 Sales per Value Chain 33 Conclusion 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BREAKING INTO THE SMALLHOLDER IDENTIFICATION OF CBSPS SEEDS MARKET By project end, 289 CBSPs (36 Oruwera CBSPs and uring its implementation over two agricultural 153 Phoenix CBSPs) had been identified, trained, and Dcampaigns between 2015 and 2017, the contracted by Phoenix and Oruwera throughout the Smallholder Effective Extension Driven Success three provinces. CBSPs were stratified into two main (SEEDS) project, implemented by NCBA CLUSA profiles: 1) smaller Lead Farmer CBSPs working with in partnership with Feed the Future Partnering for NCBA CLUSA’s Promotion of Conservation Agriculture Innovation, a USAID-funded program, supported Project (PROMAC) who managed demonstration two private sector seed firms--Phoenix Seeds and plots to promote the use of certified seed and Oruwera Seed Company--to develop agrodealer marketed this same product from their own small networks in line with NCBA CLUSA’s Community stores, and 2) larger CBSP merchants or existing Based Service Provider (CBSP) model in the agrodealers with a greater potential for seed trading. -

Manica Tambara Sofala Marromeu Mutarara Manica Cheringoma Sofala Ndoro Chemba Maringue

MOZAMBIQUE: TROPICAL CYCLONE IDAI AND FLOODS MULTI-SECTORAL LOCATION ASSESSMENT - ROUND 14 Data collection period 22 - 25 July 2020 73 sites* 19,628 households 94,220 individuals 17,005 by Cyclone Idai 82,151 by Cyclone Idai 2,623 by floods 12,069 by floods From 22 to 25 July 2020, in close coordination with Mozambique’s National Institute for Disaster Management (INGC), IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) teams conducted multi-sectoral location assessments (MSLA) in resettlement sites in the four provinces affected by Cyclone Idai (March 2019) and the floods (between December 2019 and February 2020). The DTM teams interviewed key informants capturing population estimates, mobility patterns, and multi-sectoral needs and vulnerabilities. Chemba Tete Nkganzo Matundo - unidade Chimbonde Niassa Mutarara Morrumbala Tchetcha 2 Magagade Marara Moatize Cidade de Tete Tchetcha 1 Nhacuecha Tete Tete Changara Mopeia Zambezia Sofala Caia Doa Maringue Guro Panducani Manica Tambara Sofala Marromeu Mutarara Manica Cheringoma Sofala Ndoro Chemba Maringue Gorongosa Gorongosa Mocubela Metuchira Mocuba Landinho Muanza Mussaia Ndedja_1 Sofala Maganja da Costa Nhamatanda Savane Zambezia Brigodo Inhambane Gogodane Mucoa Ronda Digudiua Parreirão Gaza Mutua Namitangurini Namacurra Munguissa 7 Abril - Cura Dondo Nicoadala Mandruzi Maputo Buzi Cidade da Beira Mopeia Maquival Maputo City Grudja (4 de Outubro/Nhabziconja) Macarate Maxiquiri alto/Maxiquiri 1 Sussundenga Maxiquiri 2 Chicuaxa Buzi Mussocosa Geromi Sofala Chibabava Maximedje Muconja Inhajou 2019 -

Traditional Prediction of Drought Under Weather and Climate Uncertainty

Natural Hazards https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-019-03613-4 ORIGINAL PAPER Traditional prediction of drought under weather and climate uncertainty: analyzing the challenges and opportunities for small‑scale farmers in Gaza province, southern region of Mozambique Daniela Salite1 Received: 5 October 2018 / Accepted: 20 April 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract This paper explores the traditional indicators that small-scale farmers in Gaza province in southern Mozambique use to predict drought events on their rain-fed farms. It analyzes the contextual situation regarding the accuracy and reliability of the traditional prediction methods under the current weather and conditions of climate uncertainty and variabil- ity, and the opportunities that their prediction methods can bring to reduce their current and future exposure and vulnerabilities to drought. Farmers use a total of 11 traditional environmental indicators to predict drought, either individually or combined, as required to increase their prediction certainty. However, the farmers perceive that current unpre- dictability, variability, and changes in weather and climate have negatively afected the interpretation, accuracy, and reliability of most of their prediction indicators, and thus their farming activities and their ability to predict and respond to drought. This, associated with the reduced number of elders in the community, is causing a decline in the diver- sity, and complexity of interpretation of indicators. Nonetheless, these difculties have not impeded farmers from continuing to use their preferred prediction methods, as on some occasions they continue to be useful for their farming-related decisions and are also the main, or sometimes only, source of forecast. Considering the role these methods play in farmers’ activities, and the limited access to meteorological forecasts in most rural areas of Mozambique, and the fact that the weather and climate is expected to continually change, this paper concludes that it is important to enhance the use of traditional prediction meth- ods. -

Angoche: an Important Link of the Zambezian Gold Trade Introduction

Angoche: An important link of the Zambezian gold trade CHRISTIAN ISENDAHL ‘Of the Moors of Angoya, they are as they were: they ruin the whole trade of Sofala.‘ Excerpt from a letter from Duarte de Lemos to the King of Portugal, dated the 30th of September, 1508 (Theal 1964, Vol. I, p. 73). Introduction During the last decade or so a significant amount of archaeological research has been devoted to the study of early urbanism along the east African coast. In much, this recent work has depended quite clearly upon the ground-breaking fieldwork conducted by James Kirkman and Neville Chittick in Kenya and Tanzania during the 1950´s and 1960´s. Notwithstanding the inevitable and, at times, fairly apparent shortcomings of their work and their basic theoretical explanatory frameworks, it has provided a platform for further detailed studies and rendered a wide flora of approaches to the interpretation of the source materials in recent studies. In Mozambique, however, recent archaeological research has not benefited from such a relatively strong national tradition of research attention. The numerous early coastal settlements lining the maritime boundaries of the nation have, in a very limited number, been the target of specialized archaeological fieldwork and analysis only for two decades. The most important consequence has been that research directed towards thematically formulated archaeological questions has had to await the gathering of basic information through field surveys and recording of existing sites as well as the construction and perpetual analysis and refinement of basic chronostratigraphic sequences. Furthermore, the lack of funding, equipment and personnel – coupled with the geographical preferentials of those actually active – has resulted in a yet quite fragmented archaeological database of early urbanism in the country. -

The Mozambican National Resistance (Renamo) As Described by Ex-Patticipants

The Mozambican National Resistance (Renamo) as Described by Ex-patticipants Research Report Submitted to: Ford Foundation and Swedish International Development Agency William Minter, Ph.D. Visiting Researcher African Studies Program Georgetown University Washington, DC March, 1989 Copyright Q 1989 by William Minter Permission to reprint, excerpt or translate this report will be granted provided that credit is given rind a copy sent to the author. For more information contact: William Minter 1839 Newton St. NW Washington, DC 20010 U.S.A. INTRODUCTION the top levels of the ruling Frelirno Party, local party and government officials helped locate amnestied ex-participants For over a decade the Mozambican National Resistance and gave access to prisoners. Selection was on the basis of the (Renamo, or MNR) has been the principal agent of a desuuctive criteria the author presented: those who had spent more time as war against independent Mozambique. The origin of the group Renamo soldiers. including commanders, people with some as a creation of the Rhodesian government in the mid-1970s is education if possible, adults rather than children. In a number of well-documented, as is the transfer of sponsorship to the South cases, the author asked for specific individuals by name, previ- African government after white Rhodesia gave way to inde- ously identified from the Mozambican press or other sources. In pendent Zimbabwe in 1980. no case were any of these refused, although a couple were not The results of the war have attracted increasing attention geographically accessible. from the international community in recent years. In April 1988 Each interview was carried out individually, out of hearing the report written by consultant Robert Gersony for the U. -

In Mozambique Melq Gomes

January 2014 Tracking Adaptation and Measuring Development (TAMD) in Mozambique Melq Gomes Q3 Report - Feasibility Testing Phase MOZAMBIQUE TAMD FEASIBILITY STUDY QUARTER THREE REPORT, 10/01/2014 Contents INTRODUCTION 2 STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS/KEY ENTRY POINTS 8 THEORY OF CHANGE ESTABLISHED 9 INDICATORS (TRACK 1 AND TRACK 2) AND METHODOLOGY 14 National level indicators 14 District level indicators 15 METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH 16 EMPIRICAL DATA COLLECTION (a) TRACK 1 (b) TRACK 2 16 CHALLENGES 17 CONCLUSIONS AND EMERGING LESSONS 17 ANNEXES 18 Annex 1: National level indicators 18 Annex 2: Guijá Field Work Report – Developing the ToC. 18 Annex 3: Draft of the workplan for Mozambique. 18 www.iied.org 1 MOZAMBIQUE TAMD FEASIBILITY STUDY QUARTER THREE REPORT, 10/01/2014 INTRODUCTION 1.1 - Mozambique Context Summary: Mozambique is the 8th most vulnerable country to climate change and is one of the poorest countries in the world with a high dependency on foreign aid. The population is primarily rural and dependent on agriculture, with 60% living on the coastline. Droughts, flooding and cyclones affect particular regions of the country and these are projected to increase in frequency and severity. The main institution for managing and coordinating climate change responses is the Ministry for Coordination of Environment Affairs (MICOA), the Ministry for Planning and Development also has a key role. New institutions have been proposed under the National Strategy on Climate Change but are not yet operational, it was approved in 2012. (Artur, Tellam 2012:8) Mozambique Climate Vulnerability and future project effects (Artur, Tellam 2012:9) Summary: The main risk/hazards in Mozambique are floods, droughts and cyclones with a very high level of current and future vulnerability in terms of exposure to floods and cyclones as more than 60% of the population lives along the coastline below 100 meters of altitude. -

Part 4: Regional Development Plan

PART 4: REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Chapter 1 Overall Conditions of the Study Area The Study on Upgrading of Nampula – Cuamba Road FINAL REPORT in the Republic of Mozambique November 2007 PART 4: REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Chapter 1 Overall Conditions of the Study Area 1.1 Existing Conditions of the Study Area The Study area consists of the two provinces of Niassa and Nampula. The total length of the Study road is approximately 350 km. In this chapter, overall conditions of the study area are described in order to prepare a regional development plan and to analyze economic, social and financial viability. The Nacala Corridor, which extends to Malawi through the Nampula and Niassa Provinces of Mozambique from Nacala Port, serves as a trucking route that connects northern agricultural zones with important cities and/or towns. In the rainy season, which is from November to April, the region has a high rainfall ranging from 1,200 to 2,000 mm. As the Study road is an unpaved road, it is frequently impassable during the rainy season, affecting the transportation of crops during this period. Looking at the 3 regions in Mozambique, results of the economic performance study conducted by UNDP over the period under analysis continue to show heavy economic concentration in the southern region of the country, with an average of about 47% of real production as can be seen in Figure 1.1.1. Within the southern region, Maputo City stands out with a contribution in real terms of about 20.8%. The central region follows, with a contribution of 32%, and finally, the northern region with only 21% of national production. -

Projectos De Energias Renováveis Recursos Hídrico E Solar

FUNDO DE ENERGIA Energia para todos para Energia CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS PORTFÓLIO HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES Edition nd 2 2ª Edição July 2019 Julho de 2019 DO POVO DOS ESTADOS UNIDOS NM ISO 9001:2008 FUNDO DE ENERGIA CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS PORTFOLIO HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES FICHA TÉCNICA COLOPHON Título Title Carteira de Projectos de Energias Renováveis - Recurso Renewable Energy Projects Portfolio - Hydro and Solar Hídrico e Solar Resources Redação Drafting Divisão de Estudos e Planificação Studies and Planning Division Coordenação Coordination Edson Uamusse Edson Uamusse Revisão Revision Filipe Mondlane Filipe Mondlane Impressão Printing Leima Impressões Originais, Lda Leima Impressões Originais, Lda Tiragem Print run 300 Exemplares 300 Copies Propriedade Property FUNAE – Fundo de Energia FUNAE – Energy Fund Publicação Publication 2ª Edição 2nd Edition Julho de 2019 July 2019 CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE RENEWABLE ENERGY ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS PROJECTS PORTFOLIO RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES PREFÁCIO PREFACE O acesso universal a energia em 2030 será uma realidade no País, Universal access to energy by 2030 will be reality in this country, mercê do “Programa Nacional de Energia para Todos” lançado por thanks to the “National Energy for All Program” launched by Sua Excia Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, Presidente da República de Moçam- His Excellency Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, President of the -

Environmental and Social Management Framework (Esmf)

REPUBLIC OF MOZAMBIQUE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT (MINEDH) IMPROVING LEARNING AND EMPOWERING GIRLS IN MOZAMBIQUE (P172657) ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK (ESMF) February, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................ 1 LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .................................................................................................. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 4 SUMARIO EXECUTIVO ................................................................................................................. 8 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 133 1.1. Overview ......................................................................................................................... 13 1.2. Scope and Objectives of the ESMF................................................................................... 15 1.3. Methodology Used to Develop ESMF .............................................................................. 15 2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS .............................. 17 2.1 The Project Area (Geographical Areas Covered) ............................................................ 177 2.2 Project Development Objective (PDO) ............................................................................ -

Manica Province

Back to National Overview OVERVIEW FOR MANICA PROVINCE Tanzania Zaire Comoros Malawi Cabo Del g ad o Niassa Zambia Nampul a Tet e Manica Zambezi a Manica Zimbabwe So f al a Madagascar Botswana Gaza Inhambane South Africa Maput o N Swaziland 200 0 200 400 Kilometers Overview for Manica Province 2 The term “village” as used herein has the same meaning as “the term “community” used elsewhere. Schematic of process. MANICA PROVINCE 678 Total Villages C P EXPERT OPINION o m l COLLECTION a n p n o i n n e g TARGET SAMPLE n t 136 Villages VISITED INACCESSIBLE 121 Villages 21 Villages LANDMINE- UNAFFECTED BY AFFECTED NO INTERVIEW LANDMINES 60 Villages 3 Villages 58 Villages 110 Suspected Mined Areas DATA ENTERED INTO D a IMSMA DATABASE t a E C n o t r m y p a MINE IMPACT SCORE (SAC/UNMAS) o n n d e A n t n a HIGH IMPACT MODERATE LOW IMPACT l y 2 Villages IMPACT 45 Villages s i s 13 Villages FIGURE 1. The Mozambique Landmine Impact Survey (MLIS) visited 9 of 10 Districts in Manica. Cidade de Chimoio was not visited, as it is considered by Mozambican authorities not to be landmine-affected. Of the 121 villages visited, 60 identified themselves as landmine-affected, reporting 110 Suspected Mined Areas (SMAs). Twenty-one villages were inaccessible, and three villages could not be found or were unknown to local people. Figure 1 provides an overview of the survey process: village selection; data collection; and data-entry into the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) database, out of which is generated the Mine Impact Score (Appendix I). -

MULTI-SECTORAL RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT POST-CYCLONE ELOISE Sofala and Manica Provinces, Mozambique Page 0 of 23

MRNA - Cyclone Eloise Miquejo community in Beira after Cyclone Eloise, Photo by Dilma de Faria MULTI-SECTORAL RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT POST-CYCLONE ELOISE Sofala and Manica Provinces, Mozambique Page 0 of 23 27 January – 5 February 2021 MRNA - Cyclone Eloise Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................. 2 Executive Summary Cyclone Eloise ............................................................................................................. 2 Key Findings ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Multi-Sectoral Recommendations ............................................................................................................. 3 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................... 5 METHODOLOGY & DATA COLLECTION .................................................................................................... 6 LIMITATIONS ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Geographical Coverage ........................................................................................................................ 7 Generalizability .....................................................................................................................................