Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Assessment for the Bigleaf Snowbell (Styrax Grandifolius Ait.)

Conservation Assessment for the Bigleaf Snowbell (Styrax grandifolius Ait.) Steven R. Hill, Ph.D. Division of Biodiversity and Ecological Entomology Biotic Surveys and Monitoring Section 1816 South Oak Street Champaign, Illinois 61820 Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Eastern Region (Region 9), Shawnee and Hoosier National Forests INHS Technical Report 2007 (65) Date of Issue: 17 December 2007 Cover photo: Styrax grandifolius Ait., from the website: In Bloom – A Monthly Record of Plants in Alabama; Landscape Horticulture at Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama. http://www.ag.auburn.edu/hort/landscape/inbloomapril99.html This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on the subject taxon or community; or this document was prepared by another organization and provides information to serve as a Conservation Assessment for the Eastern Region of the Forest Service. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service - Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 580 Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. 2 Conservation Assessment for the Bigleaf Snowbell (Styrax grandifolius Ait.) Table of Contents -

Phylogenetic Models Linking Speciation and Extinction to Chromosome and Mating System Evolution

Phylogenetic Models Linking Speciation and Extinction to Chromosome and Mating System Evolution by William Allen Freyman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology and the Designated Emphasis in Computational and Genomic Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Bruce G. Baldwin, Chair Dr. John P. Huelsenbeck Dr. Brent D. Mishler Dr. Kipling W. Will Fall 2017 Phylogenetic Models Linking Speciation and Extinction to Chromosome and Mating System Evolution Copyright 2017 by William Allen Freyman Abstract Phylogenetic Models Linking Speciation and Extinction to Chromosome and Mating System Evolution by William Allen Freyman Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology and the Designated Emphasis in Computational and Genomic Biology University of California, Berkeley Dr. Bruce G. Baldwin, Chair Key evolutionary transitions have shaped the tree of life by driving the processes of spe- ciation and extinction. This dissertation aims to advance statistical and computational ap- proaches that model the timing and nature of these transitions over evolutionary trees. These methodological developments in phylogenetic comparative biology enable formal, model- based, statistical examinations of the macroevolutionary consequences of trait evolution. Chapter 1 presents computational tools for data mining the large-scale molecular sequence datasets needed for comparative phylogenetic analyses. I describe a novel metric, the miss- ing sequence decisiveness score (MSDS), which assesses the phylogenetic decisiveness of a matrix given the pattern of missing sequence data. In Chapter 2, I introduce a class of phylogenetic models of chromosome number evolution that accommodate both anagenetic and cladogenetic change. -

Edition 2 from Forest to Fjaeldmark the Vegetation Communities Highland Treeless Vegetation

Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark The Vegetation Communities Highland treeless vegetation Richea scoparia Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark 1 Highland treeless vegetation Community (Code) Page Alpine coniferous heathland (HCH) 4 Cushion moorland (HCM) 6 Eastern alpine heathland (HHE) 8 Eastern alpine sedgeland (HSE) 10 Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) 12 Western alpine heathland (HHW) 13 Western alpine sedgeland/herbland (HSW) 15 General description Rainforest and related scrub, Dry eucalypt forest and woodland, Scrub, heathland and coastal complexes. Highland treeless vegetation communities occur Likewise, some non-forest communities with wide within the alpine zone where the growth of trees is environmental amplitudes, such as wetlands, may be impeded by climatic factors. The altitude above found in alpine areas. which trees cannot survive varies between approximately 700 m in the south-west to over The boundaries between alpine vegetation communities are usually well defined, but 1 400 m in the north-east highlands; its exact location depends on a number of factors. In many communities may occur in a tight mosaic. In these parts of Tasmania the boundary is not well defined. situations, mapping community boundaries at Sometimes tree lines are inverted due to exposure 1:25 000 may not be feasible. This is particularly the or frost hollows. problem in the eastern highlands; the class Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) is used in There are seven specific highland heathland, those areas where remote sensing does not provide sedgeland and moorland mapping communities, sufficient resolution. including one undifferentiated class. Other highland treeless vegetation such as grasslands, herbfields, A minor revision in 2017 added information on the grassy sedgelands and wetlands are described in occurrence of peatland pool complexes, and other sections. -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- ERICACEAE

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- ERICACEAE ERICACEAE (Heath Family) A family of about 107 genera and 3400 species, primarily shrubs, small trees, and subshrubs, nearly cosmopolitan. The Ericaceae is very important in our area, with a great diversity of genera and species, many of them rather narrowly endemic. Our area is one of the north temperate centers of diversity for the Ericaceae. Along with Quercus and Pinus, various members of this family are dominant in much of our landscape. References: Kron et al. (2002); Wood (1961); Judd & Kron (1993); Kron & Chase (1993); Luteyn et al. (1996)=L; Dorr & Barrie (1993); Cullings & Hileman (1997). Main Key, for use with flowering or fruiting material 1 Plant an herb, subshrub, or sprawling shrub, not clonal by underground rhizomes (except Gaultheria procumbens and Epigaea repens), rarely more than 3 dm tall; plants mycotrophic or hemi-mycotrophic (except Epigaea, Gaultheria, and Arctostaphylos). 2 Plants without chlorophyll (fully mycotrophic); stems fleshy; leaves represented by bract-like scales, white or variously colored, but not green; pollen grains single; [subfamily Monotropoideae; section Monotropeae]. 3 Petals united; fruit nodding, a berry; flower and fruit several per stem . Monotropsis 3 Petals separate; fruit erect, a capsule; flower and fruit 1-several per stem. 4 Flowers few to many, racemose; stem pubescent, at least in the inflorescence; plant yellow, orange, or red when fresh, aging or drying dark brown ...............................................Hypopitys 4 Flower solitary; stem glabrous; plant white (rarely pink) when fresh, aging or drying black . Monotropa 2 Plants with chlorophyll (hemi-mycotrophic or autotrophic); stems woody; leaves present and well-developed, green; pollen grains in tetrads (single in Orthilia). -

ABSTRACT BIAN, YANG. Genetic Diversity And

ABSTRACT BIAN, YANG. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Cultivated Blueberries (Vaccinium section Cyanococcus spp.). (Under the direction of Dr. Allan Brown). Blueberry (Vaccinium section Cyanococcus spp.) is an important small fruit crop native to North America with an incredible amount of genetic diversity that has yet to be efficiently characterized. Through broad natural and directed hybridization, the primary and secondary genepools currently utilized includes several distinct species and species hybrids in the section Cyanococcus. To date, only a limited number of cultivated blueberries have been assessed for genetic diversity in individual taxonomic groups using a limited number of molecular markers. A source of genomic SSRs is currently available through the generation and assembly of a draft genomic sequence of diploid V. corymbosum (‘W8520’). This genomic resource allows for a genome-wide survey of SSRs and the large scale development of molecular markers for blueberry genetic diversity studies and beyond. Of ~ 358 Mb genomic sequence surveyed, a total number of 43,594 SSRs were identified in 7,609 SSR-containing scaffolds (~ 122 counts per Mb). Dinucleotide repeats appeared the most abundant repeat types in all genomic regions except the predicted gene coding sequences (CDS). SSRs were most frequent and longest in 5’ untranslated region (5’ UTR), followed by 3’ UTR, while CDS contained the least frequent and shortest SSRs on average. AG/CT and AAG/CTT motifs were most frequent while CG/CG and CCG/CGG motifs were the least frequent for dinucleotide and trinucleotide motifs, respectively, in transcribed DNA. AAT/ATT motif was the most frequent trinucleotide motif in the nontranscribed DNA. -

WRA Species Report

Designation = Evaluate WRA Score = 2 Family: Ericaceae Taxon: Vaccinium virgatum Synonym: Vaccinium amoenum Aiton Common Name: Rabbit-eye blueberry Vaccinium ashei J. M. Reade Southern black blueberry Questionaire : current 20090513 Assessor: Chuck Chimera Designation: EVALUATE Status: Assessor Approved Data Entry Person: Chuck Chimera WRA Score 2 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? y=1, n=-1 103 Does the species have weedy races? y=1, n=-1 201 Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If island is primarily wet habitat, then (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High substitute "wet tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" high) (See Appendix 2) 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High high) (See Appendix 2) 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y 204 Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or subtropical climates y=1, n=0 n 205 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 ? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see n Appendix 2), n= question 205 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2) 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic y=1, n=0 n 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying -

Forests and Scrublands of Northern Fiordland

80 Vol. 1 FORESTS AND SCRUBLANDS OF NORTHERN FIORDLAND J. WARDLE, J. HAYWARD, and J. HERBERT, Forest and Range Experiment Station, New Zealand Forest Service, Rangiora (Received for publication 18 January 1971) ABSTRACT The composition and structure of the forests and scrublands of northern Fiordland were recorded at 1,053 sample points. The vegetation at each sample point was classified into one of 16 associations using a combination of Sorensen's 'k' index of similarity, and a multi-linkage cluster analysis. The associations were related to habitat and the distribution of each was determined. The influence of the introduced ungulates, red deer and wapiti, on the forests and scrublands was determined. Stand structure was analysed to provide infor mation on the susceptibility of the vegetation to damage from browsing and on the history of ungulate utilisation of the vegetation. Browse indices were calculated to provide information on current ungulate utilisation of the vegetation. INTRODUCTION A reconnaissance of northern Fiordland was carried out during the summer of 1969-70 by staff of the Forest and Range Experiment Station. The purpose was to describe the composition, structure, and habitat of the forest and scrub associations, to determine both present and past influence of ungulates on them, and to establish a number of permanent reference points to permit measurement of future changes in the vegetation. The area studied lies between the western shores of Lake Te Anau and the Tasman Sea. The southern boundary is the South Fiord of Lake Te Anau, the Esk Burn and Windward River catchments, and Charles Sound; the northern boundary is the Worsley and Transit River catchments (Fig. -

World Heritage Values and to Identify New Values

FLORISTIC VALUES OF THE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS WORLD HERITAGE AREA J. Balmer, J. Whinam, J. Kelman, J.B. Kirkpatrick & E. Lazarus Nature Conservation Branch Report October 2004 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment (World Heritage Area Vegetation Program). Commonwealth Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment or those of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. ISSN 1441–0680 Copyright 2003 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment. Published by Nature Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph: Alpine bolster heath (1050 metres) at Mt Anne. Stunted Nothofagus cunninghamii is shrouded in mist with Richea pandanifolia scattered throughout and Astelia alpina in the foreground. Photograph taken by Grant Dixon Back Cover Photograph: Nothofagus gunnii leaf with fossil imprint in deposits dating from 35-40 million years ago: Photograph taken by Greg Jordan Cite as: Balmer J., Whinam J., Kelman J., Kirkpatrick J.B. & Lazarus E. (2004) A review of the floristic values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2004/3. Department of Primary Industries Water and Environment, Tasmania, Australia T ABLE OF C ONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................................1 1. -

Manchester Road Redevelopment District: Form-Based Code

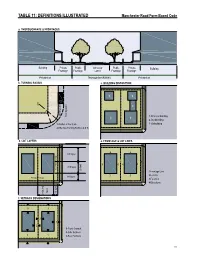

TaBle 11: deFiniTionS illuSTraTed manchester road Form-Based Code a. ThoroughFare & FronTageS Building Private Public Vehicular Public Private Building Frontage Frontage Lanes Frontage Frontage Private lot Thoroughfare (r.o.w.) Private lot b. Turning radiuS c. Building diSPoSiTion 3 3 2 2 1 Parking Lane Moving Lane 1- Principal Building 1 1 2- Backbuilding 1-Radius at the Curb 3- Outbuilding 2-Effective Turning Radius (± 8 ft) d. loT LAYERS e. FronTage & loT lineS 4 3rd layer 4 2 1 4 4 4 3 2nd layer Secondary Frontage 20 feet 1-Frontage Line 2-Lot Line 1st layer 3 3 Principal Frontage 3-Facades 1 1 4-Elevations layer 1st layer 2nd & 3rd & 2nd f. SeTBaCk deSignaTionS 3 3 2 1 2 1-Front Setback 2-Side Setback 1 1 3-Rear Setback 111 Manchester Road Form-Based Code ARTICLE 9. APPENDIX MATERIALS MBG Kemper Center PlantFinder About PlantFinder List of Gardens Visit Gardens Alphabetical List Common Names Search E-Mail Questions Menu Quick Links Home Page Your Plant Search Results Kemper Blog PlantFinder Please Note: The following plants all meet your search criteria. This list is not necessarily a list of recommended plants to grow, however. Please read about each PF Search Manchesterplant. Some may Road be invasive Form-Based in your area or may Code have undesirable characteristics such as above averageTab insect LEor disease 11: problems. NATIVE PLANT LIST Pests Plants of Merit Missouri Native Plant List provided by the Missouri Botanical Garden PlantFinder http://www.mobot.org/gardeninghelp/plantfinder Master Search Search limited to: Missouri Natives Search Tips Scientific Name Scientific Name Common NameCommon Name Height (ft.) ZoneZone GardeningHelp (ft.) Acer negundo box elder 30-50 2-10 Acer rubrum red maple 40-70 3-9 Acer saccharinum silver maple 50-80 3-9 Titles Acer saccharum sugar maple 40-80 3-8 Acer saccharum subsp. -

Supplementary Material Saving Rainforests in the South Pacific

Australian Journal of Botany 65, 609–624 © CSIRO 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/BT17096_AC Supplementary material Saving rainforests in the South Pacific: challenges in ex situ conservation Karen D. SommervilleA,H, Bronwyn ClarkeB, Gunnar KeppelC,D, Craig McGillE, Zoe-Joy NewbyA, Sarah V. WyseF, Shelley A. JamesG and Catherine A. OffordA AThe Australian PlantBank, The Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Mount Annan, NSW 2567, Australia. BThe Australian Tree Seed Centre, CSIRO, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. CSchool of Natural and Built Environments, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia DBiodiversity, Macroecology and Conservation Biogeography Group, Faculty of Forest Sciences, University of Göttingen, Büsgenweg 1, 37077 Göttingen, Germany. EInstitute of Agriculture and Environment, Massey University, Private Bag 11 222 Palmerston North 4474, New Zealand. FRoyal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Wakehurst Place, RH17 6TN, United Kingdom. GNational Herbarium of New South Wales, The Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia. HCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Table S1 (below) comprises a list of seed producing genera occurring in rainforest in Australia and various island groups in the South Pacific, along with any available information on the seed storage behaviour of species in those genera. Note that the list of genera is not exhaustive and the absence of a genus from a particular island group simply means that no reference was found to its occurrence in rainforest habitat in the references used (i.e. the genus may still be present in rainforest or may occur in that locality in other habitats). As the definition of rainforest can vary considerably among localities, for the purpose of this paper we considered rainforests to be terrestrial forest communities, composed largely of evergreen species, with a tree canopy that is closed for either the entire year or during the wet season. -

Shawnee National Forest Biological Evaluation for Regional Forester's Sensitive Plant Species

SHAWNEE NATIONAL FOREST BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION FOR REGIONAL FORESTER'S SENSITIVE PLANT SPECIES FOREST PLAN REVISION February 3, 2005 The information for the 63 Regional Forester’s sensitive plant species is taken from the Shawnee National Forest list compiled on June 15, 2004, NatureServe (2004), Plants Database (2004), the State heritage database, and available literature. Table 1. Regional Forester’s Sensitive Plant Species (RFSS) on the Forest known to occur or have been documented as historically occurring within the 11 counties of southern Illinois. An asterisk (*) denotes the assumption that the species is extirpated in that county. A double asterisk (**) next to the scientific name indicates that the name follows Mohlenbrock (1986). Note: T = Illinois Threatened, E = Illinois Endangered, EX = presumed extirpated in the State, A = Alexander, G = Gallatin, H = Hardin, Ja = Jackson, Jo = Johnson, M = Massac, Po = Pope, Pu = Pulaski, S = Saline, U = Union, and W = Williamson. Counties IL A G H Ja Jo M Po Pu S U W Scientific Name Common Name E/T X X * X 1. Amorpha nitens Shining false indigo E X X X 2. Asplenium bradleyi Bradley's spleenwort E * * X 3. Asplenium resiliens Black-stem spleenwort E X 4. Bartonia paniculata Twining screwstem E X 5. Berberis canadensis American barberry E X 6. Buchnera americana American bluehearts X 7. Calamagrostis porteri Porter’s reedgrass E ssp. insperata * X * X X 8. Carex communis Fibrous-root sedge T * X X * X 9. Carex decomposita Cypress-knee sedge E X X X X X 10. Carex gigantea Giant sedge E * * * * * * * * * 11. Carex lupuliformis False hop sedge X 12.