Gordon R. Sullivan Former Army Chief of Staff A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPRING 2017 MESSAGE from the CHAIRMAN Greetings to All USAWC Graduates and Foundation Friends

SPRING 2017 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Greetings to all USAWC graduates and Foundation friends, On behalf of our Foundation Board of Trustees, it is a privilege to share Chairman of the Board this magazine with you containing the latest news of our Foundation LTG (Ret) Thomas G. Rhame and of the U.S. Army War College (USAWC) and its graduates. Vice Chairman of the Board Our Spring Board meeting in Tampa in March was very productive as we Mr. Frank C. Sullivan planned our 2018 support to the College. We remain very appreciative Trustees and impressed with the professionalism and vision of MG Bill Rapp, LTG (Ret) Richard F. Timmons (President Emeritus) RES ’04 & 50th Commandant as he helps us understand the needs of MG (Ret) William F. Burns (President Emeritus) the College going forward. With his excellent stewardship of our Foundation support across Mrs. Charlotte H. Watts (Trustee Emerita) more than 20 programs, he has helped advance the ability of our very successful public/ Dr. Elihu Rose (Trustee Emeritus) Mr. Russell T. Bundy (Foundation Advisor) private partnership to provide the margin of excellence for the College and its grads. We also LTG (Ret) Dennis L. Benchoff thank so many of you who came to our USAWC Alumni Dinner in Tampa on March 15, Mr. Steven H. Biondolillo 2017 (feature and photos on page 7). Special thanks to GEN Joseph L. Votel III, RES ’01, Mr. Hans L. Christensen and GEN Raymond A. Th omas III, RES ’00, for hosting us at the Central and Special Ms. Jo B. Dutcher Operations Commands at MacDill AFB on March 17th. -

Trump's Generals

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Trump’s Generals: A Natural Experiment in Civil-Military Relations JAMES JOYNER Abstract President Donald Trump’s filling of numerous top policy positions with active and retired officers he called “my generals” generated fears of mili- tarization of foreign policy, loss of civilian control of the military, and politicization of the military—yet also hope that they might restrain his worst impulses. Because the generals were all gone by the halfway mark of his administration, we have a natural experiment that allows us to com- pare a Trump presidency with and without retired generals serving as “adults in the room.” None of the dire predictions turned out to be quite true. While Trump repeatedly flirted with civil- military crises, they were not significantly amplified or deterred by the presence of retired generals in key roles. Further, the pattern continued in the second half of the ad- ministration when “true” civilians filled these billets. Whether longer-term damage was done, however, remains unresolved. ***** he presidency of Donald Trump served as a natural experiment, testing many of the long- debated precepts of the civil-military relations (CMR) literature. His postelection interviewing of Tmore than a half dozen recently retired four- star officers for senior posts in his administration unleashed a torrent of columns pointing to the dangers of further militarization of US foreign policy and damage to the military as a nonpartisan institution. At the same time, many argued that these men were uniquely qualified to rein in Trump’s worst pro- clivities. With Trump’s tenure over, we can begin to evaluate these claims. -

Lessons-Encountered.Pdf

conflict, and unity of effort and command. essons Encountered: Learning from They stand alongside the lessons of other wars the Long War began as two questions and remind future senior officers that those from General Martin E. Dempsey, 18th who fail to learn from past mistakes are bound Excerpts from LChairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: What to repeat them. were the costs and benefits of the campaigns LESSONS ENCOUNTERED in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what were the LESSONS strategic lessons of these campaigns? The R Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University was tasked to answer these questions. The editors com- The Institute for National Strategic Studies posed a volume that assesses the war and (INSS) conducts research in support of the Henry Kissinger has reminded us that “the study of history offers no manual the Long Learning War from LESSONS ENCOUNTERED ENCOUNTERED analyzes the costs, using the Institute’s con- academic and leader development programs of instruction that can be applied automatically; history teaches by analogy, siderable in-house talent and the dedication at the National Defense University (NDU) in shedding light on the likely consequences of comparable situations.” At the of the NDU Press team. The audience for Washington, DC. It provides strategic sup- strategic level, there are no cookie-cutter lessons that can be pressed onto ev- Learning from the Long War this volume is senior officers, their staffs, and port to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman ery batch of future situational dough. The only safe posture is to know many the students in joint professional military of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified com- historical cases and to be constantly reexamining the strategic context, ques- education courses—the future leaders of the batant commands. -

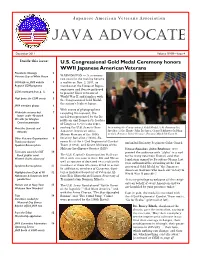

JAVA Advocate, December 2011 Edition

Japanese American Veterans Association JAVA ADVOCATE December 2011 Volume XVIIII—Issue 4 Inside this issue: U.S. Congressional Gold Medal Ceremony honors WWII Japanese American Veterans President’s Message 2 Veterans Day at White House WASHINGTON — A ceremony two years in the making became CGM info on JAVA website 3 a reality on Nov. 2, 2011, as Regional CGM programs members of the House of Repre- sentatives and Senate gathered CGM (continued from p. 1) 4 to present Nisei veterans of World War II and families with High praise for CGM events 5 the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest honor. JAVA members photos 6 With scores of photographers Wakatake receives best 7 recording the moment, the lawyer under 40 award medal was presented by the Re- Wreaths for Arlington publican and Democratic leaders Cemetery gravesites of Congress to veterans repre- Meet the Generals and 8 senting the U.S. Army’s three Presenting the Congressional Gold Medal, L-R: Susumu Ito, Admirals Japanese American units: Speaker of the House John Boehner, Grant Ichikawa (holding Mitsuo Hamasu of the 100th medal), Senator Daniel Inouye, Senator Mitch McConnell. Other Veterans Organizations 9 Infantry Battalion (100th), Su- Thank you donors! sumu Ito of the 442nd Regimental Combat ion/442nd Infantry Regiment Color Guard. Speakers Bureau photo Team (442nd), and Grant Ichikawa of the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). House Speaker John Boehner, who Tucci wins award for SGT 10 greeted the audience with “aloha” in a nod Rock graphic novel The U.S. Capitol’s Emancipation Hall was to the many vets from Hawaii, said that Wanted: Stories about you! filled with veterans in their 80s and 90s as legislation signed by President Obama last well as spouses of deceased vets and family year authorized the awarding of the Con- Speakers Bureau photos 11 members of those who were killed in action. -

1999 Annual Report

Army and Air Force Mutual Aid Association 121st Annual Report For the year ended 31 December 1999 1879 OVER 120 YEARS OF SERVICE 1999 Organized 13 January 1879 121st Annual Report For the year ended 31 December 1999 Army and Air Force Mutual Aid Association 102 Sheridan Avenue Fort Myer, Virginia 22211-1110 Branch office located in Pentagon Concourse (north end) Toll free: 1-800-336-4538 Local: 703-522-3060 (recorded messages after hours) FAX: 703-522-1336 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.aafmaa.com Office hours: 8:30 A.M.–4:30 P.M. EST Monday–Friday Night depository at both locations 1 2 3 ASSOCIATION DIRECTORS CHAIR General Robert W. Sennewald VICE CHAIR Lieutenant General Donald M. Babers BOARD OF DIRECTORS Term expires 2001: Lieutenant General Donald M. Babers Terms expire 2002: Lieutenant General Henry Doctor, Jr. Colonel Wayne T. Fujito Lieutenant General Bradley C. Hosmer Major General Susan L. Pamerleau* Captain Bradley J. Snyder, CLU Terms expire 2003: Major William D. Clark Major Joe R. Reeder Command Sergeant Major Jimmie W. Spencer Terms expire 2004: General Michael P.C. Carns Lieutenant General John A. Dubia Major General Michael J. Nardotti, Jr. Brigadier General L. Donne Olvey Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force Sam E. Parish General Robert W. Sennewald CHAIRS EMERITI General Walter T. Kerwin, Jr. General Michael S. Davison DIRECTORS EMERITI General John R. Guthrie Brigadier General Elizabeth P. Hoisington ASSOCIATION OFFICERS President Captain Bradley J. Snyder, CLU Vice President for Services & Secretary Major Joseph J. Francis, CLU, ChFC Vice President for Finance & Treasurer Major Walter R. -

JAVA Advocate--October 2011

Japanese American Veterans Association JAVA ADVOCATE October 2011 Volume XVIIII—Issue 3 Inside this issue: Over 400 Japanese American WWII Veterans to participate in Congressional Gold Medal Events President’s Message 2 WASHINGTON — The Congressional Legacy of the Nisei Veteran 3 Gold Medal (CGM), the highest award the nation can bestow, will be awarded Kaho’ohanohano receives 4 collectively to the 100th Infantry Battal- Medal of Honor ion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and the Military Intelligence Service in a Martin Luther King, Jr. 5 ceremony at the Emancipation Hall of Memorial the U.S. Congress on Nov. 2, 2011. Ap- FFNV Reunion in Las Vegas 6 proximately 1,250 veterans, spouses, widows, families of soldiers who were Inouye receives award from 7 killed in combat and deceased veterans Japan were invited by the Speaker of the House McNaughton joins JAVA for of Representatives, John Boehner, to at- 23 Hawaii WW II veterans will wear blue blaz- lunch tend the program. ers similar to that worn by Herbert Yanamura (center), MIS veteran, when they are awarded Meet the Generals and 8 Those who are unable to attend the CGM the Congressional Gold Medal on November 3rd. Admirals ceremony at the U.S. Capitol will watch Tammy Kubo (left) and MG Robert Lee (right) the program live at the Hilton Washing- obtained donors to underwrite this endeavor. Other Veterans Organizations 9 ton Hotel. The original CGM will be re- (Courtesy of Tammy Kubo) Thank you donors! trieved following the presentation and The World War II Nisei Memorial Pro- Wanted: Articles about you! will be archived at the Smithsonian Insti- gram will be held on Nov. -

Where Have You Gone George C. Marshall? Colonel Douglas A

Photo courtesy of the George C. Marshall Foundation Where Have You Gone George C. Marshall? Colonel Douglas A. LeVien United States Army here have you gone George C. Marshall? Dr. Forrest Pogue’s illuminating authorized, 1 four–volume, 1,900 page, biography of George C. Marshall published between 1963 and 1987, is the definitive, indispensable account of the “true organizer of victory” and W 1 America’s global role in the post World War II world. Pogue’s masterpiece is an enduring monument to the life of one of America’s greatest soldiers, statesmen, humanitarians, peacemakers, and architects of success. The historian Douglas Freeman once observed that when Marshall’s colleagues asked themselves what were his most noble character virtues, they immediately turned to Thomas Jefferson’s testimonial to George Washington: “His integrity was most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motives of interest or consanguinity, of friendship or hatred, being able to bias his decisions.”2 “Succeeding generations,” Winston Churchill insisted, “must not be allowed to forget his achievements and his example.”3 Marshall was a leadership genius whose guiding principles are timeless and worthy of emulation. Yet after 14-plus years of endless conflict following the attacks of September 11, 2001, and for considerable spans of the last half-century, the United States has largely ignored his example. In an era when too many of our public and private leaders are more interested in their personal or special interests, and more concerned about prestige than selflessness, it is absolutely necessary to reflect upon how Marshall would have prevented the best military in the world from misguided, endless wars and provided the world’s lone superpower with the strategic vision to navigate in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous environment. -

Iraq Study Group Consultations

CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF THE PRESIDENCY IRAQ STUDY GROUP Iraq Study Group Consultations (* denotes meeting took place in Iraq) Iraqi Officials and Representatives * Jalal Talabani - President * Tareq al-Hashemi - Vice President * Adil Abd al-Mahdi - Vice President * Nouri Kamal al-Maliki - Prime Minister * Salaam al-Zawbai - Deputy Prime Minister * Barham Salih - Deputy Prime Minister * Mahmoud al-Mashhadani - Speaker of the Parliament * Mowaffak al-Rubaie - National Security Advisor * Jawad Kadem al-Bolani - Minister of Interior * Abdul Qader Al-Obeidi - Minister of Defense * Hoshyar Zebari - Minister of Foreign Affairs * Bayan Jabr - Minister of Finance * Hussein al-Shahristani - Minster of Oil * Karim Waheed - Minister of Electricity * Akram al-Hakim - Minister of State for National Reconciliation Affairs * Mithal al-Alusi - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Ayad Jamal al-Din - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Ali Khalifa al-Duleimi - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Sami al-Ma'ajoon - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Muhammad Ahmed Mahmoud - Member, Commission on National Reconciliation * Wijdan Mikhael - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation Lt. General Nasir Abadi - Deputy Chief of Staff of the Iraqi Joint Forces * Adnan al-Dulaimi - Head of the Tawafuq list Ali Allawi - Former Minister of Finance * Sheik Najeh al-Fetlawi - representative of Muqtada al-Sadr * Abd al-Aziz al-Hakim - Shia Coalition Leader * Sheik Maher al-Hamraa - Ayat Allah -

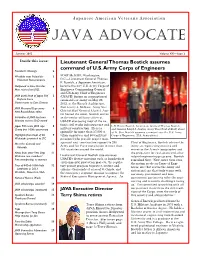

JAVA-Advocate-Summer

Japanese American Veterans Association JAVA ADVOCATE Summer 2012 Volume XX—Issue 2 Inside this issue: Lieutenant General Thomas Bostick assumes command of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers President’s Message 2 Westdale visits Poland for 3 FORT McNAIR, Washington, Holocaust Remembrance D.C.—Lieutenant General Thomas P. Bostick, a Japanese American, Hollywood as Exec Director 4 became the 53rd U.S. Army Corps of Mori retires from JACL Engineers Commanding General and US Army Chief of Engineers JAVA briefs head of Japan Self 5 (USACE) during an assumption of Defense Force command ceremony on May 22, Shima retires as Exec Director 2012, at the Baruch Auditorium, JAVA Memorial Day events 6 Fort Lesley J. McNair. Army Vice New Round Robin editor Chief of Staff General Lloyd J. Aus- tin hosted the event. Bostick serves Caravalho at JAVA luncheon 7 as the senior military officer at Ishimoto receives DoD award USACE overseeing most of the na- Japan PM meets JAVA reps 8 tion’s civil works infrastructure and L-R: Renee Bostick, Lieutenant General Thomas Bostick, Cherry tree 100th anniversary military construction. He is re- and General Lloyd J. Austin, Army Vice Chief of Staff, stand sponsible for more than 37,000 ci- at Lt. Gen. Bostick assumes command over the U.S. Army Highlights from Dept of VA 9 vilian employees and 600 military Corps of Engineers. (U.S. Army photo) Wakatake promoted to LTC personnel who provide project man- agement and construction support to 250 Chief of Engineers, Bostick advises the Meet the Generals and 10 Admirals Army and Air Force installation in more than Army on engineering matters and 100 countries around the world. -

RAO BULLETIN 15 May 2020

RAO BULLETIN 15 May 2020 PDF Edition THIS RETIREE ACTIVITIES OFFICE BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Pg Article Subject . * DOD * . 04 == DOD Watch ---- (Being Maintained Despite Pandemic) 05 == Coronavirus Disinformation ---- (China’s Exploitation of the Pandemic) 06 == PCS Moves [10] ---- (30,000 Military Families to Move during Stop-Movement Order) 06 == DOD Immigrant Soldier Citizenship ---- (Lawsuit | Promise Broken by U.S). 07 == Military Medicine [02] ---- (Congress Must Stop the Attempt to Dismantle) 09 == Marine Corps Readiness [04] ---- (Forming a First-of-its-Kind Regiment in Hawaii) 10 == MilSpouse Money Mission ---- (New DoD Website for Military Spouses) 11 == POW/MIA Recoveries & Burials ---- (Reported 01 thru 15 May 2020 | Ten) . * VA * . 13 == Memorial Day [01] ---- (VA National Cemeteries to Commemorate 22 MAY) 14 == VA Operations ---- (3-Part Plan to Resume Full Services) 15 == VA Coronavirus Preparations [05] ---- (Rising Capacity, Supplies, & Staffing 8 weeks In) 15 == VA COVID-19 National Summary [01] ---- (Reporting Summary Tool Enhanced) 16 == VA COVID-19 National Summary [02] ---- (More Than 5,000 Veterans Are in Recovery) 17 == VA Referrals ---- (Agency Probe Requested on COVID-19 Handling) 18 == Homeless Vets [100] ---- (CARES Act Funding Expands VA Support Services) 19 == Homeless Vets [101] ---- (COVID-19 Aid Bill Create Tent Cities in VA Parking Lots) 20 == VA Mobile Apps [02] ---- (COVID-19 Coach Available for Download) 21 == VA Veteran Homes [01] ---- (Senate Probe Sought After COVID-19 Deaths) 22 == Burn Pit Toxic Exposure [76] ---- (Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry Update) 1 23 == VA COVID-19 Deaths [01] ---- (African American & Hispanic Warning) 24 == Agent Orange Exposure Locations [03] ---- (White Paper Identifies Guam 13 Year Exposure Period) 25 == VA Cemeteries [22] ---- (Gravestones Bearing Nazi Swastikas Removal Request Rejected) 25 == VA Fraud, Waste & Abuse ---- (Reported 01 thru 15 MAY 2020) . -

Washington Update

WASHINGTON UPDATE A MONTHLY NEWSLETTER Vol. 11 No. 5 Published by the AUSA Institute of Land Warfare Mav 1999 Shinseki nominated as chief of staff. Secretary Promoted to general in August 1997, he became the com of Defense William S. Cohen announced April 21 that manderin chief, United States Army, Europe, and 7th Army, President Clinton has nominated Gen. EricK Shinseki to and commander of the Stabilization Force in Bosnia become the Army's chief of staff. Shinseki will succeed Herzegovena. While in Europe, he also commanded soldiers Gen. Dennis J. Reimer who will retire June 21. Reimer from several NATO countries as the commander, Allied served in this position for four years. Land Forces Central Europe. Commenting on the nomination, AUSA President Gen. In 1998, Shinseki was called back to the Pentagon to Gordon R. Sullivan, USA, Ret., said, "Ric Shinseki is an become the Army's28th vice chief of staff. In this position, dynamic, inspirational, compassionate and effective leader he chaired several councils and committees that have an who has proven in combat and in troop and staffpositions impact on the day-to-day operations and futureplans of the that he is the right soldier at the right time to lead America's total Army- active, Army National Guard and United Army into the next millenium. States Army Reserve- as it prepares to enter the 21st century. "AUSA, with its I 00,000 members, urges the Senate to confirm Gen. Shinseki as soon as possible. He's a great They include: the Army Space Council, the Reserve Com American; he's a soldier's soldier." ponent Coordination Council, the Army Reserve Action Plan General OfficerSteering Committee and the Special Born in Lihue on the island of Kauai, Hawaii, in 1942, Access Program Oversight Committee. -

JAVA Advocate Apr-May 2010

Japanese American Veterans Association JAVA ADVOCATE April/May 2010 Volume XVIII—Issue 1 Inside this issue: Shinseki receives JAVA Courage, Honor, Patriotism Award; pays tribute to Japanese American Veterans President’s Message 2 Ellis Island Exhibit 3 FALLS CHURCH, Vir. — Gen- JAVA Board changes eral Eric K. Shinseki, Secretary Shinseki recognized 4 of the Department of Veterans Affairs, received the COUR- Wounded warrior takes 5 AGE, HONOR, PATRIOTISM Command Award from the Japanese 100th Bn mail reviewed American Veterans Association Japan Lieutenants visit USA 6 (JAVA) in recognition of his 44 G Company, 442nd reunion years of distinguished leader- ship in the United States Army MOH/DSC recipients 7 and in the Department of Veter- recognized ans Affairs. The Award was House of Reps roundtable presented on January 16, 2010 at JAVA’s annual meeting in Highlights from DVA 8 White House seeks $ for vets Falls Church, Virginia. The award is bestowed on persons Secretary Shinseki (left) holding COURAGE, HONOR, PA- Pirates! 9 who exemplify the spirit of cour- TRIOTISM Award with JAVA President Robert Nakamoto Students visit Japan Embassy age, honor and patriotism dem- (right). onstrated by the Nisei soldiers Meet the Generals, Admirals 10 during World War II. and health care they have earned.” Bostick promoted 11 President Nakamoto said Asian Ameri- Heart Mt Leadership Summit Over 150 JAVA members, families and friends, including veterans of the 442nd cans, including Japanese Americans, MIS Vets meet CG Kamo 12 Regimental Combat Team and the are proud of Secretary Shinseki’s accom- Frankeberger retires plishments: the first Asian American to Military Intelligence Service, about a dozen flag ranked officers, and veter- be appointed as Chief of Staff of the US Other Veterans organizations 13 Army and the third Asian American to DVD on Japanese American ans who served in the Korean, Vietnam experience and Gulf Wars expressed their enthusi- be appointed to a cabinet rank position.