Where Have You Gone George C. Marshall? Colonel Douglas A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPRING 2017 MESSAGE from the CHAIRMAN Greetings to All USAWC Graduates and Foundation Friends

SPRING 2017 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Greetings to all USAWC graduates and Foundation friends, On behalf of our Foundation Board of Trustees, it is a privilege to share Chairman of the Board this magazine with you containing the latest news of our Foundation LTG (Ret) Thomas G. Rhame and of the U.S. Army War College (USAWC) and its graduates. Vice Chairman of the Board Our Spring Board meeting in Tampa in March was very productive as we Mr. Frank C. Sullivan planned our 2018 support to the College. We remain very appreciative Trustees and impressed with the professionalism and vision of MG Bill Rapp, LTG (Ret) Richard F. Timmons (President Emeritus) RES ’04 & 50th Commandant as he helps us understand the needs of MG (Ret) William F. Burns (President Emeritus) the College going forward. With his excellent stewardship of our Foundation support across Mrs. Charlotte H. Watts (Trustee Emerita) more than 20 programs, he has helped advance the ability of our very successful public/ Dr. Elihu Rose (Trustee Emeritus) Mr. Russell T. Bundy (Foundation Advisor) private partnership to provide the margin of excellence for the College and its grads. We also LTG (Ret) Dennis L. Benchoff thank so many of you who came to our USAWC Alumni Dinner in Tampa on March 15, Mr. Steven H. Biondolillo 2017 (feature and photos on page 7). Special thanks to GEN Joseph L. Votel III, RES ’01, Mr. Hans L. Christensen and GEN Raymond A. Th omas III, RES ’00, for hosting us at the Central and Special Ms. Jo B. Dutcher Operations Commands at MacDill AFB on March 17th. -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

The Courage of General Matthew Ridgway

The Courage of General Matthew Ridgway Full Lesson Plan COMPELLING QUESTION How can acting with courage help you accomplish your identity and purpose? VIRTUE Courage DEFINITION Courage is the capacity to overcome fear in order to do good. LESSON OVERVIEW In this lesson, students will explore the life of Matthew Ridgway and his role in the Korean War. Students will understand how Matthew Ridgway’s courage helped save the United States’ and United Nations’ forces during the Korean War. Through his example, they will learn how they can use courage in their own lives to accomplish their purpose. OBJECTIVES • Students will analyze General Matthew Ridgway’s performance during the Korean War. • Students will understand how to use courage to accomplish their purpose. • Students will apply their knowledge of courage to their own lives. BACKGROUND The Korean War was an outgrowth of an unstable situation on the Korean Peninsula at the conclusion of the Second World War. In August 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on the Empire of Japan. With the endorsement of the United States, Soviet forces seized land in the northern part of the peninsula, stopping at the 38th Parallel. The United States then occupied the southern half. Two different political regimes with opposing views emerged from this situation, creating the perfect recipe for conflict. War broke out in June 1950. North Korea, hoping to assert its dominance over the entire peninsula, invaded South Korea and made quick progress. South Korea, supported by United States and United https://voicesofhistory.org BACKGROUND Nations forces, fell back around the port city of Pusan. -

February 21, 2010 Transcript

© 2010, CBS Broadcasting Inc. All Rights Reserved. PLEASE CREDIT ANY QUOTES OR EXCERPTS FROM THIS CBS TELEVISION PROGRAM TO "CBS NEWS' FACE THE NATION." February 21, 2010 Transcript GUEST: GEN. COLIN POWELL Former Secretary of State MODERATOR/ HOST: Mr. BOB SCHIEFFER CBS News This is a rush transcript provided for the information and convenience of the press. Accuracy is not guaranteed. In case of doubt, please check with FACE THE NATION - CBS NEWS (202) 457-4481 TRANSCRIPT BOB SCHIEFFER: Today on FACE THE NATION, an exclusive interview with Colin Powell. He holds a unique place in American life: soldier, diplomat, advisor to both Republican and Democratic Presidents. What does he make of the Washington gridlock? Does he think the system is broken? What would he do to fix it? We'll ask him. Then I'll have a personal thought on why Washington doesn't listen, or does it? It's all next on FACE THE NATION. ANNOUNCER: FACE THE NATION with CBS News chief Washington correspondent Bob Schieffer. And now, from CBS News in Washington, Bob Schieffer. BOB SCHIEFFER: And good morning again. The former secretary of state, the former chairman of the joint chiefs is in the studio with us this morning. General, you do bring a unique perspective to this. You're a Republican but you have held high- level positions under both Republicans and Democrats. And when you announced that you were voting for Barack Obama in 2008, it really got the nation's attention. Here's part of what you said. COLIN POWELL (Former Secretary of State) (Meet the Press, October 19, 2008): Because of his ability to inspire, because of the inclusive nature of his campaign, because he is reaching out all across America, he has both style and substance, he has met the standard of being a successful President, being an exceptional President. -

Trump's Generals

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Trump’s Generals: A Natural Experiment in Civil-Military Relations JAMES JOYNER Abstract President Donald Trump’s filling of numerous top policy positions with active and retired officers he called “my generals” generated fears of mili- tarization of foreign policy, loss of civilian control of the military, and politicization of the military—yet also hope that they might restrain his worst impulses. Because the generals were all gone by the halfway mark of his administration, we have a natural experiment that allows us to com- pare a Trump presidency with and without retired generals serving as “adults in the room.” None of the dire predictions turned out to be quite true. While Trump repeatedly flirted with civil- military crises, they were not significantly amplified or deterred by the presence of retired generals in key roles. Further, the pattern continued in the second half of the ad- ministration when “true” civilians filled these billets. Whether longer-term damage was done, however, remains unresolved. ***** he presidency of Donald Trump served as a natural experiment, testing many of the long- debated precepts of the civil-military relations (CMR) literature. His postelection interviewing of Tmore than a half dozen recently retired four- star officers for senior posts in his administration unleashed a torrent of columns pointing to the dangers of further militarization of US foreign policy and damage to the military as a nonpartisan institution. At the same time, many argued that these men were uniquely qualified to rein in Trump’s worst pro- clivities. With Trump’s tenure over, we can begin to evaluate these claims. -

Soldiers and Statesmen

, SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.65 Stock Number008-070-00335-0 Catalog Number D 301.78:970 The Military History Symposium is sponsored jointly by the Department of History and the Association of Graduates, United States Air Force Academy 1970 Military History Symposium Steering Committee: Colonel Alfred F. Hurley, Chairman Lt. Colonel Elliott L. Johnson Major David MacIsaac, Executive Director Captain Donald W. Nelson, Deputy Director Captain Frederick L. Metcalf SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN The Proceedings of the 4th Military History Symposium United States Air Force Academy 22-23 October 1970 Edited by Monte D. Wright, Lt. Colonel, USAF, Air Force Academy and Lawrence J. Paszek, Office of Air Force History Office of Air Force History, Headquarters USAF and United States Air Force Academy Washington: 1973 The Military History Symposia of the USAF Academy 1. May 1967. Current Concepts in Military History. Proceedings not published. 2. May 1968. Command and Commanders in Modem Warfare. Proceedings published: Colorado Springs: USAF Academy, 1269; 2d ed., enlarged, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1972. 3. May 1969. Science, Technology, and Warfare. Proceedings published: Washington, b.C.: Government Printing Office, 197 1. 4. October 1970. Soldiers and Statesmen. Present volume. 5. October 1972. The Military and Society. Proceedings to be published. Views or opinions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and are not to be construed as carrying official sanction of the Department of the Air Force or of the United States Air Force Academy. -

Kissinger's World: a Cautionary Tale Through a Cold War Lens Book Review*

Kissinger's World: A Cautionary Tale Through a Cold War Lens Book Review* MICHAEL J. KELLY** Henry Kissinger, former National Security Advisor and Secretary of State in the Nixon and Ford administrations, Nobel Peace Laureate, co- Man of the Year for Time Magazine, and widely regarded "dean of American foreign policy" is an eloquent writer. He is persuasive, avuncular, and sometimes grandiose. His internal logic is mostly consistent and coherent. He is perhaps one of the greatest diplomats of his generation. Henry Kissinger is also a man of the Cold War generation. This book reflects his latest attempt to bring meaning to the multipolar world that has emerged around him, but it equally reflects his more general inability to do so, as he continues to cling to notions of unipolarity with America at the center. An unfortunate theme is Kissinger's predictable distraction by geopolitical and geostrategic considerations that enjoyed more relevance during his tenure in office than today. Does America Need a Foreign Policy? is clearly a rhetorical title intended to stir interest in what Dr. Kissinger rightly perceives as waning American concern for international affairs. This book is designed to offer a general stock-taking of our current situation in the world as we move into the 21st century-hence the subtitle, Toward a Diplomacyfor the 21st Century. While the book does not neatly outline a comprehensive new foreign policy, package it with all the trimmings and deliver it to Secretary of State Powell for immediate implementation, it does create a * Henry Kissinger, Does America Need a Foreign Policy (Simon & Schuster 2001). -

10, George C. Marshall

'The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense or the US Government.'" USAFA Harmon Memorial Lecture #10 “George C. Marshall: Global Commander” Forrest C. Pogue, 1968 It is a privilege to be invited to give the tenth lecture in a series which has become widely-known among teachers and students of military history. I am, of course, delighted to talk with you about Gen. George C. Marshall with whose career I have spent most of my waking hours since1956. Douglas Freeman, biographer of two great Americans, liked to say that he had spent twenty years in the company of Gen. Lee. After devoting nearly twelve years to collecting the papers of General Marshall and to interviewing him and more than 300 of his contemporaries, I can fully appreciate his point. In fact, my wife complains that nearly any subject from food to favorite books reminds me of a story about General Marshall. If someone serves seafood, I am likely to recall that General Marshall was allergic to shrimp. When I saw here in the audience Jim Cate, professor at the University of Chicago and one of the authors of the official history of the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, I recalled his fondness for the works of G.A. Henty and at once there came back to me that Marshall once said that his main knowledge of Hannibal came from Henty's The Young Carthaginian. If someone asks about the General and Winston Churchill, I am likely to say, "Did you know that they first met in London in 1919 when Marshall served as Churchill's aide one afternoon when the latter reviewed an American regiment in Hyde Park?" Thus, when I mentioned to a friend that I was coming to the Air Force Academy to speak about Marshall, he asked if there was much to say about the General's connection with the Air Force. -

Lessons-Encountered.Pdf

conflict, and unity of effort and command. essons Encountered: Learning from They stand alongside the lessons of other wars the Long War began as two questions and remind future senior officers that those from General Martin E. Dempsey, 18th who fail to learn from past mistakes are bound Excerpts from LChairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: What to repeat them. were the costs and benefits of the campaigns LESSONS ENCOUNTERED in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what were the LESSONS strategic lessons of these campaigns? The R Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University was tasked to answer these questions. The editors com- The Institute for National Strategic Studies posed a volume that assesses the war and (INSS) conducts research in support of the Henry Kissinger has reminded us that “the study of history offers no manual the Long Learning War from LESSONS ENCOUNTERED ENCOUNTERED analyzes the costs, using the Institute’s con- academic and leader development programs of instruction that can be applied automatically; history teaches by analogy, siderable in-house talent and the dedication at the National Defense University (NDU) in shedding light on the likely consequences of comparable situations.” At the of the NDU Press team. The audience for Washington, DC. It provides strategic sup- strategic level, there are no cookie-cutter lessons that can be pressed onto ev- Learning from the Long War this volume is senior officers, their staffs, and port to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman ery batch of future situational dough. The only safe posture is to know many the students in joint professional military of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified com- historical cases and to be constantly reexamining the strategic context, ques- education courses—the future leaders of the batant commands. -

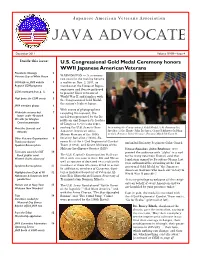

JAVA Advocate, December 2011 Edition

Japanese American Veterans Association JAVA ADVOCATE December 2011 Volume XVIIII—Issue 4 Inside this issue: U.S. Congressional Gold Medal Ceremony honors WWII Japanese American Veterans President’s Message 2 Veterans Day at White House WASHINGTON — A ceremony two years in the making became CGM info on JAVA website 3 a reality on Nov. 2, 2011, as Regional CGM programs members of the House of Repre- sentatives and Senate gathered CGM (continued from p. 1) 4 to present Nisei veterans of World War II and families with High praise for CGM events 5 the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest honor. JAVA members photos 6 With scores of photographers Wakatake receives best 7 recording the moment, the lawyer under 40 award medal was presented by the Re- Wreaths for Arlington publican and Democratic leaders Cemetery gravesites of Congress to veterans repre- Meet the Generals and 8 senting the U.S. Army’s three Presenting the Congressional Gold Medal, L-R: Susumu Ito, Admirals Japanese American units: Speaker of the House John Boehner, Grant Ichikawa (holding Mitsuo Hamasu of the 100th medal), Senator Daniel Inouye, Senator Mitch McConnell. Other Veterans Organizations 9 Infantry Battalion (100th), Su- Thank you donors! sumu Ito of the 442nd Regimental Combat ion/442nd Infantry Regiment Color Guard. Speakers Bureau photo Team (442nd), and Grant Ichikawa of the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). House Speaker John Boehner, who Tucci wins award for SGT 10 greeted the audience with “aloha” in a nod Rock graphic novel The U.S. Capitol’s Emancipation Hall was to the many vets from Hawaii, said that Wanted: Stories about you! filled with veterans in their 80s and 90s as legislation signed by President Obama last well as spouses of deceased vets and family year authorized the awarding of the Con- Speakers Bureau photos 11 members of those who were killed in action. -

BOOK REVIEW: the Generals

BOOK REVIEWS end simply is wearing stars, not leading of the institution and concerns over the the military properly into the next century senior leader’s career compete for consider- and candidly rendering their best military ation in the decision space. In an effort to advice to our nation’s civilian leaders. demonstrate an example of “doing it right” Ricks convincingly traces modern in the modern era, Ricks reaches deep failures of generalship to their origins below the senior-leader level to examine in the interwar period, through World the relief of Colonel Joe Dowdy, USMC, War II, Korea, Vietnam, and Operations the commander of First Marine Regiment Desert Storm, Iraqi Freedom, and Enduring in the march to Baghdad. Dowdy’s (not Freedom. He juxtaposes successful Army uncontroversial) relief demonstrates that and Marine generals through their histories there is no indispensable man, and if a com- with the characteristics of history’s failed mander loses confidence in a subordinate, generals. Ricks draws specific, substanti- the subordinate must go. In Ricks’s view, if The Generals: American Military ated conclusions about generalship, Army it is a close call, senior leaders should err on Command from World War II to Today culture, civil-military relations, and the the side of relief: the human and strategic By Thomas E. Ricks way the Army has elected to organize, train, costs of getting that call wrong are virtually Penguin Press, 2012 and equip itself in ways that ultimately unconscionable. Ricks rightly concludes 576 pp. $32.95 suboptimized Service performance. Specifi- that too much emphasis has been placed ISBN: 978-1-59420-404-3 cally identifying the Army’s modern-era on the “career consequence” of relief for reluctance to effect senior leader reliefs as individual officers. -

1999 Annual Report

Army and Air Force Mutual Aid Association 121st Annual Report For the year ended 31 December 1999 1879 OVER 120 YEARS OF SERVICE 1999 Organized 13 January 1879 121st Annual Report For the year ended 31 December 1999 Army and Air Force Mutual Aid Association 102 Sheridan Avenue Fort Myer, Virginia 22211-1110 Branch office located in Pentagon Concourse (north end) Toll free: 1-800-336-4538 Local: 703-522-3060 (recorded messages after hours) FAX: 703-522-1336 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.aafmaa.com Office hours: 8:30 A.M.–4:30 P.M. EST Monday–Friday Night depository at both locations 1 2 3 ASSOCIATION DIRECTORS CHAIR General Robert W. Sennewald VICE CHAIR Lieutenant General Donald M. Babers BOARD OF DIRECTORS Term expires 2001: Lieutenant General Donald M. Babers Terms expire 2002: Lieutenant General Henry Doctor, Jr. Colonel Wayne T. Fujito Lieutenant General Bradley C. Hosmer Major General Susan L. Pamerleau* Captain Bradley J. Snyder, CLU Terms expire 2003: Major William D. Clark Major Joe R. Reeder Command Sergeant Major Jimmie W. Spencer Terms expire 2004: General Michael P.C. Carns Lieutenant General John A. Dubia Major General Michael J. Nardotti, Jr. Brigadier General L. Donne Olvey Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force Sam E. Parish General Robert W. Sennewald CHAIRS EMERITI General Walter T. Kerwin, Jr. General Michael S. Davison DIRECTORS EMERITI General John R. Guthrie Brigadier General Elizabeth P. Hoisington ASSOCIATION OFFICERS President Captain Bradley J. Snyder, CLU Vice President for Services & Secretary Major Joseph J. Francis, CLU, ChFC Vice President for Finance & Treasurer Major Walter R.