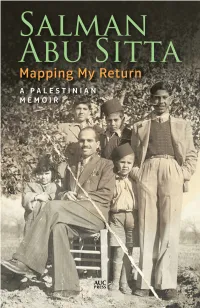

Mapping My Return: a Palestinian Memoir Salman Abu Sitta New York, Cairo, the American University in Cairo Press, 2016, 332 Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palestinian Refugees: Adiscussion ·Paper

Palestinian Refugees: ADiscussion ·Paper Prepared by Dr. Jan Abu Shakrah for The Middle East Program/ Peacebuilding Unit American Friends Service Committee l ! ) I I I ' I I I I I : Contents Preface ................................................................................................... Prologue.................................................................................................. 1 Introduction . .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 The Creation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem .. .. .. .. .. 3 • Identifying Palestinian Refugees • Counting Palestinian Refugees • Current Location and Living Conditions of the Refugees Principles: The International Legal Framework .... .. ... .. .. ..... .. .. ....... ........... 9 • United Nations Resolutions Specific to Palestinian Refugees • Special Status of Palestinian Refugees in International Law • Challenges to the International Legal Framework Proposals for Resolution of the Refugee Problem ...................................... 15 • The Refugees in the Context of the Middle East Peace Process • Proposed Solutions and Principles Espoused by Israelis and Palestinians Return Statehood Compensation Resettlement Work of non-governmental organizations................................................. 26 • Awareness-Building and Advocacy Work • Humanitarian Assistance and Development • Solidarity With Right of Return and Restitution Conclusion .... ..... ..... ......... ... ....... ..... ....... ....... ....... ... ......... .. .. ... .. ............ -

The Nakba: 70 Years ON

May 2018 Photo: Abed Rahim Khatib Photo: A I THE NAKBA: 70 YEARS ON 70 Years of Dispossession, Displacement and Denial of Rights, but also ASS 70 Years of Steadfastness, Self-Respect and Struggle for Freedom and Justice P INTRODUCTION 2018 is the year where Palestinians all over the world remember the 70th anniversary of the Nakba - 70 Years in which they had their civil and national rights trampled on, sacrificed lives and livelihoods, had their land stolen, their property destroyed, promises broken, were injured, insulted and humiliated, endured oppression, dispersion, imprisonment and torture, and witnessed numerous attempts to partition their homeland and divide their people. However, despite all past and ongoing land confiscation, settlement construction, forcible displacements and rights denials, the Zionist movement has failed to empty the country of its indigenous Palestinian inhabitants, whose number has meanwhile increased to an extent that it is about to exceed that of the Jews. Despite all repressions at the hands of the occupier, despite all attempts at erasing or distorting their history and memory, and despite all political setbacks and failed negotiations, Palestinians are still steadfast on their land and resisting occupation. The 1948 Nakba remains the root cause of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and will continue to fuel the Palestinian struggle for freedom and self-determination. As clearly reflected in the ‘Great March of Return’ which began on 30 March 2018 along the Gaza border fence, the Palestinians will not relinquish their historical and legal right of return to their homeland nor their demand that Israel acknowledges Contents: its moral and political responsibility for this ongoing tragedy and the gross injustice inflicted on the Palestinian people. -

CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project

CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY WORKING PAPER NO. 6 STUDIES JULY 2003 Searching for Solutions PALESTINIAN REFUGEES HOW CAN A DURABLE SOLUTION BE ACHIEVED? TANJA SALEM This Working Paper is published by the CEPS Middle East and Euro-Med Project. The project addresses issues of policy and strategy of the European Union in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the wider issues of EU relations with the countries of the Barcelona Process and the Arab world. Participants in the project include independent experts from the region and the European Union, as well as a core team at CEPS in Brussels led by Michael Emerson and Nathalie Tocci. Support for the project is gratefully acknowledged from: • Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino • Department for International Development (DFID), London. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed are attributable only to the author in a personal capacity and not to any institution with which he is associated. ISBN 92-9079-429-1 CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project Available for free downloading from the CEPS website (http://www.ceps.be) Copyright 2003, CEPS Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1 • B-1000 Brussels • Tel: (32.2) 229.39.11 • Fax: (32.2) 219.41.41 e-mail: [email protected] • website: http://www.ceps.be CONTENTS 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Background..................................................................................................................................... -

Rights in Principle – Rights in Practice, Revisiting the Role of International Law in Crafting Durable Solutions

Rights in Principle - Rights in Practice Revisiting the Role of International Law in Crafting Durable Solutions for Palestinian Refugees Terry Rempel, Editor BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights, Bethlehem RIGHTS IN PRINCIPLE - RIGHTS IN PRACTICE REVISITING THE ROLE OF InternatiONAL LAW IN CRAFTING DURABLE SOLUTIONS FOR PALESTINIAN REFUGEES Editor: Terry Rempel xiv 482 pages. 24 cm ISBN 978-9950-339-23-1 1- Palestinian Refugees 2– Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons 3- International Law 4– Land and Property Restitution 5- International Protection 6- Rights Based Approach 7- Peace Making 8- Public Participation HV640.5.P36R53 2009 Cover Photo: Snapshots from «Go and See Visits», South Africa, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cyprus and Palestine (© BADIL) Copy edit: Venetia Rainey Design: BADIL Printing: Safad Advertising All rights reserved © BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights December 2009 P.O. Box 728 Bethlehem, Palestine Tel/Fax: +970 - 2 - 274 - 7346 Tel: +970 - 2 - 277 - 7086 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.badil.org iii CONTENTS Abbreviations ....................................................................................vii Contributors ......................................................................................ix Foreword ..........................................................................................xi Foreword .........................................................................................xiv Introduction ......................................................................................1 -

When the Carob Tree Was the Border

When the Carob Tree Was the Border: On autonomy and Palestinian practices of figuring it out† Linda Quiquivix* Introduction “How did they know where the borders were?” I ask, “If people didn’t have maps, how did they know?” Ahmed Al-Noubani opens his arm out and points. “It was that carob tree,” he says, “to that carob tree.” “Neighbors,” he shrugs. They figured it out. Al-Noubani and I are in his office at Bir Zeit University’s geography department, discussing histories of Palestinian map-making.1 Palestinians did not really start making maps, he says, until after Oslo.2 When the leadership first began negotiating with Israel over sovereignty in the West Bank and Gaza, the Palestinian side had no maps of its own. In fact, the first maps of the country that Yasser Arafat signed in the negotiations were ones that belonged to, and had been fully drafted by, the Israeli side.3 Recognizing the new urgency to map, the Palestinian leadership would later † I presented a draft of this work under the title “Defending the Palestinian Commons” at the Historical Materialism Conference in New York City, 26-28 April 2013. The final version benefited greatly from the discussion and I thank Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro for arranging our gathering there. In preparing this article for publication, I must also acknowledge the centrality of my sustained discussions with Alvaro Reyes, Denis Wood, Yousuf Al-Bulushi, Mayssun Sukarie, Ahmad Al-Nimer, and Salim Tamari on many of the topics I address here. My conversations with Nidal Al-Azzraq in Aida Refugee Camp have shaped much of my thinking on Palestine and cartography. -

![[Review] Salman Abu Sitta(2016) Mapping My Return: a Palestinian Memoir](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4464/review-salman-abu-sitta-2016-mapping-my-return-a-palestinian-memoir-2244464.webp)

[Review] Salman Abu Sitta(2016) Mapping My Return: a Palestinian Memoir

[Review] Salman Abu Sitta(2016) Mapping my return: a Palestinian memoir Article (Accepted Version) Irfan, Anne (2017) [Review] Salman Abu Sitta(2016) Mapping my return: a Palestinian memoir. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 44 (2). pp. 283-284. ISSN 1353-0194 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/70542/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Mapping My Return: A Palestinian Memoir Salman Abu Sitta New York, Cairo, The American University in Cairo Press, 2016, 332 pp. -

Palestinian Refugees This Page Intentionally Left Blank Palestinian Refugees Challenges of Repatriation and Development

Palestinian Refugees This page intentionally left blank Palestinian Refugees Challenges of Repatriation and Development Edited by Rex Brynen and Roula El-Rifai International Development Research Centre Ottawa · Cairo · Dakar · Montevideo · Nairobi · New Delhi · Singapore Published in 2007 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd and the International Development Research Centre 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com International Development Research Centre PO Box 8500 Ottawa, ON KIG 3H9 Canada [email protected]/www.idrc.ca ISBN (e-book) 978–1–55250–231–0 In the United States of America and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan a division of St. Martin’s Press 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © International Development Research Centre 2007 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 978 1 84511 311 7 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available Typeset by Jayvee, Trivandrum, India Printed and bound in Great Britain by T J International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall Contents List of figures and tables vii List of contributors x Preface and acknowledgements xvi Glossary xix 1 Introduction: Refugee -

Mapping Exile and Return

1 “Homecoming Is Out of the Question” Palestinian Refugee Cartography and Edward Said’s View from Exile “Forgetfulness leads to exile, while remembrance is the secret of redemption.” The Palestinian refugee activist Salman Abu-Sitta deploys this quotation, which he attributes to the Baal Shem Tov, as one of the epigraphs to his “register of depopulated locales in Palestine,” one of Abu-Sitta’s initial attempts to document the dispossession and forced exile of Palestinians by Zionist militias in 1948, named by Palestinians as the .1 Memory for Abu-Sitta represents nakba a moral demand placed upon refugees: failure to cultivate memory, the epigraph suggests, will prolong refugees’ exile, whereas proper attention to memory will hasten redemption understood as the physical return of refugees to their homes.2 Abu-Sitta displays little interest in the mystical Hasidic framework within which the Baal Shem Tov’s conceptions of exile and redemption operated, one in which exile referred most fundamentally to the estrangement of the people Israel (and by extension, humanity) from God, with redemption correspondingly understood as the mystical cleaving of the soul to God. The epigraphic appeal to the Baal Shem Tov does not point to a mystical dimension to Abu-Sitta’s effort to document the ravages of the , but rather reflects nakba how Abu-Sitta self-consciously locates the Palestinian refugee case within the symbolic discourse of Jewish exile and return. This discursive move is reinforced by another epigraph in Abu-Sitta’s registry of over five hundred destroyed Palestinian towns and villages, a citation from Lam. 5:1–2: “Remember, O God, what has befallen us; behold, and see our disgrace! Our inheritance has been turned over to strangers, our homes to aliens.”3 Abu-Sitta maps Palestinian exile onto Jewish exile and Palestinian refugee memory onto Jewish remembrance of . -

Al Nakba Background

Atlas of Palestine 1917 - 1966 SALMAN H. ABU-SITTA PALESTINE LAND SOCIETY LONDON Chapter 3: The Nakba Chapter 3 The Nakba 3.1 The Conquest down Palestinian resistance to British policy. The The immediate aim of Plan C was to disrupt Arab end of 1947 marked the greatest disparity between defensive operations, and occupy Arab lands The UN recommendation to divide Palestine the strength of the Jewish immigrant community situated between isolated Jewish colonies. This into two states heralded a new period of conflict and the native inhabitants of Palestine. The former was accompanied by a psychological campaign and suffering in Palestine which continues with had 185,000 able-bodied Jewish males aged to demoralize the Arab population. In December no end in sight. The Zionist movement and its 16-50, mostly military-trained, and many were 1947, the Haganah attacked the Arab quarters in supporters reacted to the announcement of veterans of WWII.244 Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa, killing 35 Arabs.252 On the 1947 Partition Plan with joy and dancing. It December 18, 1947, the Palmah, a shock regiment marked another step towards the creation of a The majority of young Jewish immigrants, men established in 1941 with British help, committed Jewish state in Palestine. Palestinians declared and women, below the age of 29 (64 percent of the first reported massacre of the war in the vil- a three-day general strike on December 2, 1947 population) were conscripts.245 Three quarters of lage of al-Khisas in the upper Galilee.253 In the first in opposition to the plan, which they viewed as the front line troops, estimated at 32,000, were three months of 1948, Jewish terrorists carried illegal and a further attempt to advance western military volunteers who had recently landed in out numerous operations, blowing up buses and interests in the region regardless of the cost to Palestine.246 This fighting force was 20 percent of Palestinian homes. -

The Palestinians in Israel Readings in History, Politics and Society

The Palestinians in Israel Readings in History, Politics and Society Edited by Nadim N. Rouhana and Areej Sabbagh-Khoury 2011 Mada al-Carmel Arab Center for Applied Social Research The Palestinians in Israel: Readings in History, Politics and Society Edited by: Nadim N. Rouhana and Areej Sabbagh-Khoury اﻟﻔﻠﺴﻄﻴﻨﻴﻮن ﰲ إﴎاﺋﻴﻞ: ﻗﺮاءات ﰲ اﻟﺘﺎرﻳﺦ، واﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﺔ، واملﺠﺘﻤﻊ ﺗﺤﺮﻳﺮ: ﻧﺪﻳﻢ روﺣﺎﻧﺎ وأرﻳﺞ ﺻﺒﺎغ-ﺧﻮري Editorial Board: Muhammad Amara, Mohammad Haj-Yahia, Mustafa Kabha, Rassem Khamaisi, Adel Manna, Khalil-Nakhleh, Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Mahmoud Yazbak Design and Production: Wael Wakeem ISBN 965-7308-18-6 © All Rights Reserved July 2011 by Mada Mada al-Carmel–Arab Center for Applied Social Research 51 Allenby St., P.O. Box 9132 Haifa 31090, Israel Tel. +972 4 8552035, Fax. +972 4 8525973 www.mada-research.org [email protected] 2 The Palestinians in Israel: Readings in History, Politics and Society Table of Contents Introduction Research on the Palestinians in Israel: Between the Academic and the Political 5 Areej Sabbagh-Khoury and Nadim N. Rouhana The Nakba 16 Honaida Ghanim The Internally Displaced Palestinians in Israel 26 Areej Sabbagh-Khoury The Military Government 47 Yair Bäuml The Conscription of the Druze into the Israeli Army 58 Kais M. Firro Emergency Regulations 67 Yousef Tayseer Jabareen The Massacre of Kufr Qassem 74 Adel Manna Yawm al-Ard (Land Day) 83 Khalil Nakhleh The Higher Follow-Up Committee for the Arab Citizens in Israel 90 Muhammad Amara Palestinian Political Prisoners 100 Abeer Baker National Priority Areas 110 Rassem Khamaisi The Indigenous Palestinian Bedouin of the Naqab: Forced Urbanization and Denied Recognition 120 Ismael Abu-Saad Palestinian Citizenship in Israel 128 Oren Yiftachel 3 Mada al-Carmel Arab Center for Applied Social Research Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to a group of colleagues who helped make possible the project of writing this book and producing it in three languages. -

From Balfour to the Nakba

Friday 12th to Thursday 18th May 2017 “Expelling people from their homes is FROM BALFOUR a war crime. As well as preventing them TO THE NAKBA: from returning. Israel WEEK OF ACTION didn’t just commit a war crime in 1948 but continues to commit Palestine Solidarity Campaign one to this day.” Resource Pack Salman Abu Sitta, author, www.palestinecampaign.org/campaigns/ Atlas Of Palestine 1948 balfour2nakba #Balfour2Nakba #Balfour2Nakba 1 Contents Introduction to the Week of Action 3 Background 4 Factsheets 6 Infographics and maps 7 Recommended articles 8 Short videos and testimonies 9 Suggestions for film screenings 11 Recommended books 13 Images, poems and music 14 What you can do 15 Get in touch 16 #Balfour2Nakba 2 Introduction to the Week of Action Palestine Solidarity Campaign will be launching a series of events to mark the 69th anniversary of the Palestinians’ loss of their homes and land when the state of Israel was created in 1948. The loss, known by Palestinians as the Nakba or ‘Catastrophe’, was the violent dispossession and removal of the native Palestinian population from their towns and villages. This year also marks the centenary of the Balfour Declaration, when the UK government pledged its support for the Zionist movement’s desire for a Jewish state in Palestine. British complicity in Israel’s racist violence and land theft continues to this day. This pack has been put together to assist you in facilitating your own Nakba Week events. It contains suggestions of films for film screenings, and videos and articles for sharing. For the full list of our Nakba Week of Action events please see: www.palestinecampaign.org/campaigns/ balfour2nakba #Balfour2Nakba 3 Background Every year Palestinians mark the Nakba – “catastrophe” in English – when in 1948 around 750,000 Palestinians were forcibly expelled from their homes during the creation of the state of Israel. -

Mapping My Return

Mapping My Return Mapping My Return A Palestinian Memoir SALMAN ABU SITTA The American University in Cairo Press Cairo New York This edition published in 2016 by The American University in Cairo Press 113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt 420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 www.aucpress.com Copyright © 2016 by Salman Abu Sitta All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Exclusive distribution outside Egypt and North America by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd., 6 Salem Road, London, W2 4BU Dar el Kutub No. 26166/14 ISBN 978 977 416 730 0 Dar el Kutub Cataloging-in-Publication Data Abu Sitta, Salman Mapping My Return: A Palestinian Memoir / Salman Abu Sitta.—Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2016 p. cm ISBN 978 977 416 730 0 1. Beersheba (Palestine)—History—1914–1948 956.9405 1 2 3 4 5 20 19 18 17 16 Designed by Amy Sidhom Printed in the United States of America To my parents, Sheikh Hussein and Nasra, the first generation to die in exile To my daughters, Maysoun and Rania, the first generation to be born in exile Contents Preface ix 1. The Source (al-Ma‘in) 1 2. Seeds of Knowledge 13 3. The Talk of the Hearth 23 4. Europe Returns to the Holy Land 35 5. The Conquest 61 6. The Rupture 73 7. The Carnage 83 8.