The Gaza Strip As Laboratory: Notes in the Wake of Disengagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project

CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY WORKING PAPER NO. 9 STUDIES JUNE 2003 Searching for Solutions THE NEW WALLS AND FENCES: CONSEQUENCES FOR ISRAEL AND PALESTINE GERSHON BASKIN WITH SHARON ROSENBERG This Working Paper is published by the CEPS Middle East and Euro-Med Project. The project addresses issues of policy and strategy of the European Union in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the wider issues of EU relations with the countries of the Barcelona Process and the Arab world. Participants in the project include independent experts from the region and the European Union, as well as a core team at CEPS in Brussels led by Michael Emerson and Nathalie Tocci. Support for the project is gratefully acknowledged from: • Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino • Department for International Development (DFID), London. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed are attributable only to the author in a personal capacity and not to any institution with which he is associated. ISBN 92-9079-436-4 Available for free downloading from the CEPS website (http://www.ceps.be) CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project Copyright 2003, CEPS Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1 • B-1000 Brussels • Tel: (32.2) 229.39.11 • Fax: (32.2) 219.41.41 e-mail: [email protected] • website: http://www.ceps.be THE NEW WALLS AND FENCES – CONSEQUENCES FOR ISRAEL AND PALESTINE WORKING PAPER NO. 9 OF THE CEPS MIDDLE EAST & EURO-MED PROJECT * GERSHON BASKIN WITH ** SHARON ROSENBERG ABSTRACT ood fences make good neighbours’ wrote the poet Robert Frost. Israel and Palestine are certainly not good neighbours and the question that arises is will a ‘G fence between Israel and Palestine turn them into ‘good neighbours’. -

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

From Cold Peace to Cold War?: the Significance of Egypt's Military

FROM COLD PEACE TO COLD WAR? THE SIGNIFICANCE OF EGYPT’S MILITARY BUILDUP Jeffrey Azarva* Since the 1978 Camp David Accords, the Egyptian government has undertaken extraordinary efforts to modernize its military with Western arms and weapon systems. By bolstering its armored corps, air force, and naval fleet with an array of U.S. military platforms, the Egyptian armed forces have emerged as one the region’s most formidable forces. But as the post-Husni Mubarak era looms, questions abound. Who, precisely, is Egypt arming against, and why? Has Egypt attained operational parity with Israel? How will the military be affected by a succession crisis? Could Cairo’s weapons arsenal fall into the hands of Islamists? This essay will address these and other questions by analyzing the regime’s procurement of arms, its military doctrine, President Mubarak’s potential heirs, and the Islamist threat. INTRODUCTION force to a modernized, well-equipped, Western-style military. In March 1999, then U.S. Secretary of Outfitted with some of the most Defense William Cohen embarked on a sophisticated U.S. weapons technology, nine-nation tour of the Middle East to Egypt’s arsenal has been significantly finalize arms agreements worth over $5 improved—qualitatively as well as billion with regional governments. No state quantitatively—in nearly every military received more military hardware than branch. While assimilating state-of-the-art Egypt. Totaling $3.2 billion, Egypt’s arms weaponry into its order of battle, the package consisted of 24 F-16D fighter Egyptian military has also decommissioned planes, 200 M1A1 Abrams tanks, and 32 Soviet equipment or upgraded outdated Patriot-3 missiles.1 Five months later, Cairo ordnance. -

Palestinian Refugees: Adiscussion ·Paper

Palestinian Refugees: ADiscussion ·Paper Prepared by Dr. Jan Abu Shakrah for The Middle East Program/ Peacebuilding Unit American Friends Service Committee l ! ) I I I ' I I I I I : Contents Preface ................................................................................................... Prologue.................................................................................................. 1 Introduction . .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 The Creation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem .. .. .. .. .. 3 • Identifying Palestinian Refugees • Counting Palestinian Refugees • Current Location and Living Conditions of the Refugees Principles: The International Legal Framework .... .. ... .. .. ..... .. .. ....... ........... 9 • United Nations Resolutions Specific to Palestinian Refugees • Special Status of Palestinian Refugees in International Law • Challenges to the International Legal Framework Proposals for Resolution of the Refugee Problem ...................................... 15 • The Refugees in the Context of the Middle East Peace Process • Proposed Solutions and Principles Espoused by Israelis and Palestinians Return Statehood Compensation Resettlement Work of non-governmental organizations................................................. 26 • Awareness-Building and Advocacy Work • Humanitarian Assistance and Development • Solidarity With Right of Return and Restitution Conclusion .... ..... ..... ......... ... ....... ..... ....... ....... ....... ... ......... .. .. ... .. ............ -

Ottawa Jewish Bulletin

THANK YOU FOR SUPPORTING What A Wonderful Chanukah Gift To Give... JNF NEGEV DINNER 2017 An Ottawa Jewish HONOURING LAWRENCE GREENSPON Bulletin Subscription JNFOTTAWA.CA FOR DETAILS [email protected] 613.798.2411 Call 613-798-4696, Ext. 256 Ottawa Jewish Bulletin NOVEMBER 27, 2017 | KISLEV 9, 5778 ESTABLISHED 1937 OTTAWAJEWISHBULLETIN.COM | $2 JNF honours Lawrence Greenspon at Negev Dinner BY NORAH MOR ore than 500 people filled the sold-out Infinity Convention Centre, November 6, to celebrate 2017 honouree Lawrence Greenspon at the Jewish National Fund M(JNF) of Ottawa’s annual Negev dinner. Greenspon, a well-known criminal defence attorney and civil litigator, also has a long history as a devoted community activist and fundraiser. A past chair of the Ottawa Jewish Community Centre and the United Way Community Services Cabinet, Greenspon has initiat- ed a number of health-based events and campaigns and has been previously honoured with many awards including a Lifetime Achievement Award from Volun- teer Ottawa and the Community Builder of the Year Award by the United Way. Rabbi Reuven Bulka, the Negev Dinner MC, praised Greenspon’s creative fundraising ideas using “boxing, motorcycles, paddling races and even hockey and dancing events.” Negev Dinner honouree Lawrence Greenspon receives his citation from the Jewish National Fund of Canada, November 6, at the “Lawrence has touched so many of us, in so many Infinity Convention Centre, ways, by devoting endless hours, and being a voice (From left) Negev Dinner Chair David Feldberg, Carter Grusys, Lawrence Greenspon, Maja Greenspon, Angela Lariviere, JNF for those who don’t have a voice,” said Negev Dinner National President Wendy Spatzner, Major General (Res) Doron Almog, JNF Ottawa President Dan Mader (partially hidden), and Chair David Feldberg in his remarks. -

Arrested Development: the Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank

B’TSELEM - The Israeli Information Center for ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT Human Rights in the Occupied Territories 8 Hata’asiya St., Talpiot P.O. Box 53132 Jerusalem 91531 The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Tel. (972) 2-6735599 | Fax (972) 2-6749111 Barrier in the West Bank www.btselem.org | [email protected] October 2012 Arrested Development: The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank October 2012 Research and writing Eyal Hareuveni Editing Yael Stein Data coordination 'Abd al-Karim Sa'adi, Iyad Hadad, Atef Abu a-Rub, Salma a-Deb’i, ‘Amer ‘Aruri & Kareem Jubran Translation Deb Reich Processing geographical data Shai Efrati Cover Abandoned buildings near the barrier in the town of Bir Nabala, 24 September 2012. Photo Anne Paq, activestills.org B’Tselem would like to thank Jann Böddeling for his help in gathering material and analyzing the economic impact of the Separation Barrier; Nir Shalev and Alon Cohen- Lifshitz from Bimkom; Stefan Ziegler and Nicole Harari from UNRWA; and B’Tselem Reports Committee member Prof. Oren Yiftachel. ISBN 978-965-7613-00-9 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Part I The Barrier – A Temporary Security Measure? ................. 7 Part II Data ....................................................................... 13 Maps and Photographs ............................................................... 17 Part III The “Seam Zone” and the Permit Regime ..................... 25 Part IV Case Studies ............................................................ 43 Part V Violations of Palestinians’ Human Rights due to the Separation Barrier ..................................................... 63 Conclusions................................................................................ 69 Appendix A List of settlements, unauthorized outposts and industrial parks on the “Israeli” side of the Separation Barrier .................. 71 Appendix B Response from Israel's Ministry of Justice ....................... -

West Bank and Gaza 2020 Human Rights Report

WEST BANK AND GAZA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Palestinian Authority basic law provides for an elected president and legislative council. There have been no national elections in the West Bank and Gaza since 2006. President Mahmoud Abbas has remained in office despite the expiration of his four-year term in 2009. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not functioned since 2007, and in 2018 the Palestinian Authority dissolved the Constitutional Court. In September 2019 and again in September, President Abbas called for the Palestinian Authority to organize elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council within six months, but elections had not taken place as of the end of the year. The Palestinian Authority head of government is Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh. President Abbas is also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and general commander of the Fatah movement. Six Palestinian Authority security forces agencies operate in parts of the West Bank. Several are under Palestinian Authority Ministry of Interior operational control and follow the prime minister’s guidance. The Palestinian Civil Police have primary responsibility for civil and community policing. The National Security Force conducts gendarmerie-style security operations in circumstances that exceed the capabilities of the civil police. The Military Intelligence Agency handles intelligence and criminal matters involving Palestinian Authority security forces personnel, including accusations of abuse and corruption. The General Intelligence Service is responsible for external intelligence gathering and operations. The Preventive Security Organization is responsible for internal intelligence gathering and investigations related to internal security cases, including political dissent. The Presidential Guard protects facilities and provides dignitary protection. -

Gaza Crossings' Operations Status: Monthly

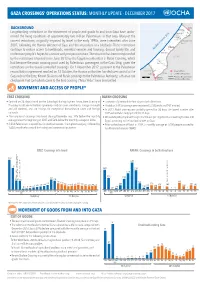

GAZA CROSSINGS’ OPERATIONS STATUS: MONTHLY UPDATE - DECEMBER 2017 BACKGROUND Erez Beit Lahiya ¹ ! Longstanding restrictions on the movement of people and goods to and from Gaza have under- ! Jabalya ! Beit Hanoun mined the living conditions of approximately two million Palestinians in that area. Many of the Gaza City ! n Sea ! Ash Shuja’iyeh current restrictions, originally imposed by Israel in the early 1990s, were intensified after June anea Nahal Oz Karni 2007, following the Hamas takeover of Gaza and the imposition of a blockade. These restrictions iterr GAZA Med 21 continue to reduce access to livelihoods, essential services and housing, disrupt family life, and 30! 0 undermine people’s hopes for a secure and prosperous future. The situation has been compounded Deir al B alah by the restrictions imposed since June 2013 by the Egyptian authorities at Rafah Crossing, which ISRAEL ! had become the main crossing point used by Palestinian passengers in the Gaza Strip, given the Khan Yunis Khuza’a ! restrictions on the Israeli-controlled crossings. On 1 November 2017, pursuant to the Palestinian 14389 Rafah EGYPT ! Crossing Point reconciliation agreement reached on 12 October, the Hamas authorities handed over control of the Sufa Rafah¹º» Closed Crossing Point Armistice Declaration Line Gaza side of the Erez, Kerem Shalom and Rafah crossings to the Palestinian Authority; a Hamas-run 5 Km ¹º» Kerem checkpoint that controlled access to the Erez crossing (“Arba’ Arba’”) was dismantled. Shalom International Boundary MOVEMENT AND ACCESS OF PEOPLE* EREZ CROSSING RAFAH CROSSING • Opened on 26 days (closed on five Saturdays) during daytime hours, from Sunday to • Exceptionally opened for four days in both directions. -

Israel-Jordan Cooperation: a Potential That Can Still Be Fulfilled

Israel-Jordan Cooperation: A Potential That Can Still Be Fulfilled Published as part of the publication series: Israel's Relations with Arab Countries: The Unfulfilled Potential Yitzhak Gal May 2018 Israel-Jordan Cooperation: A Potential That Can Still Be Fulfilled Yitzhak Gal* May 2018 The history of Israel-Jordan relations displays long-term strategic cooperation. The formal peace agreement, signed in 1994, has become one of the pillars of the political-strategic stability of both Israel and Jordan. While the two countries have succeeded in developing extensive security cooperation, the economic, political, and civil aspects, which also have great cooperation potential, have for the most part been neglected. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict presents difficulties in realizing this potential while hindering the Israel-Jordan relations and leading to alienation and hostility between the two peoples. However, the formal agreements and the existing relations make it possible to advance them even under the ongoing conflict. Israel and Jordan can benefit from cooperation on political issues, such as promoting peace and relations with the Palestinians and managing the holy sites in Jerusalem; they can also benefit from cooperation on civil matters, such as joint management of water resources, and resolving environmental, energy, and tourism issues; and lastly, Israel can benefit from economic cooperation while leveraging the geographical position of Jordan which makes it a gateway to Arab markets. This article focuses on the economic aspect and demonstrates how such cooperation can provide Israel with a powerful growth engine that will significantly increase Israeli GDP. It draws attention to the great potential that Israeli-Jordanian ties engender, and to the possibility – which still exists – to realize this potential, which would enhance peaceful and prosperous relationship between Israel and Jordan. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs LEBANON SYRIA West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009 West Bank Gaza Strip JORDAN Barta'a ISRAEL ¥ EGYPT Area Affected r The Barrier’s total length is 709 km, more than e v i twice the length of the 1949 Armistice Line R n (Green Line) between the West Bank and Israel. W e s t B a n k a d r o The total area located between the Barrier J and the Green Line is 9.5 % of the West Bank, Qalqilya including East Jerusalem and No Man's Land. Qedumim Finger When completed, approximately 15% of the Barrier will be constructed on the Green Line or in Israel with 85 % inside the West Bank. Biddya Area Populations Affected Ari’el Finger If the Barrier is completed based on the current route: Az Zawiya Approximately 35,000 Palestinians holding Enclave West Bank ID cards in 34 communities will be located between the Barrier and the Green Line. The majority of Palestinians with East Kafr Aqab Jerusalem ID cards will reside between the Barrier and the Green Line. However, Bir Nabala Enclave Biddu Palestinian communities inside the current Area Shu'fat Camp municipal boundary, Kafr Aqab and Shu'fat No Man's Land Camp, are separated from East Jerusalem by the Barrier. Ma’ale Green Line Adumim Settlement Jerusalem Bloc Approximately 125,000 Palestinians will be surrounded by the Barrier on three sides. These comprise 28 communities; the Biddya and Biddu areas, and the city of Qalqilya. ISRAEL Approximately 26,000 Palestinians in 8 Gush a communities in the Az Zawiya and Bir Nabala Etzion e Enclaves will be surrounded on four sides Settlement S Bloc by the Barrier, with a tunnel or road d connection to the rest of the West Bank. -

Palestinian Territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY and WEST ASIA

Palestinian territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY AND WEST ASIA Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - LOWER MIDDLE INCOME Local currency - Israeli new shekel (ILS) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 6 020 km2 GDP: 19.4 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 4 509 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), an increase 4.295 REAL GDP GROWTH: -1.5% (2014 vs 2013) of 3% per year (2010-2014) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 26.9% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 713 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 127 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 75.3% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 18.6% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: Ramallah (2% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.677 (medium), rank 113 Sources: World Bank; UNDP-HDR, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government RESPONSIBILITIES MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 483 - - 483 Local governments - Municipalities (baladiyeh) Average municipal size: 8 892 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. The Palestinian Authority was born from the Oslo Agreements. Palestine is divided into two main geographical units: the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It is still an ongoing State construction. The official government of Cisjordania is governed by a President, while the Gaza area is governed by the Hamas. Up to now, most governmental functions are ensured by the State of Israel. In 1994, and upon the establishment of the Palestinian Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), 483 local government units were created, encompassing 103 municipalities and village councils and small clusters. Besides, 16 governorates are also established as deconcentrated level of government.