Sylvie and Bruno and the Loss of Innocence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Good Morning!»: Una Broma Filológica En the Hobbit

«Good Morning!»: una broma filológica en The Hobbit 1. Un hobbit bien educado El señor Bilbo Baggins, Esq., es un hobbit bien educado. La primera vez que lo escuchamos está ofreciendo un «Good Morning!» a un anciano tocado con un pintoresco sombrero en la soleada mañana en que este se plantó ante su puerta (H, i, 5-7). Nada menos se podía esperar del hijo de los señores Bungo Baggins y Belladona Took, un hobbit respetable, vástago de una familia respetable. Con razón comenzó a inquietarse al escuchar la palabra «adventure» salir de los labios del ahora inoportuno visitante. Con exquisito tacto intentó despedirlo utilizando la misma expresión de la bienvenida. Impertinente, el anciano desveló su nombre, Gandalf, e insistió en su propósito. Gracias a la providencia, al final, nuestro asustado hobbit pudo regresar a la seguridad de su hogar sin mayor daño. Desde el comienzo, The Hobbit está impregnado con ese tono cómico del que el autor, J. R. R. Tolkien, va a renegar con posterioridad. El estudio del humor en esta obra es un camino fecundo: permite saborear parte de los ingredientes que el Profesor introdujo en el caldero. Unos ingredientes quizás menos nobles y elevados que otros bien conocidos. Fijar la mirada en el pequeño fragmento de la conversación inicial es perfecto para mostrar los mecanismos que Tolkien utiliza. Un lectura demorada del mismo muestra que la formación filológica del autor es esencial para desentrañar las referencias implícitas. Por ejemplo, las constantes alusiones al significado de las expresiones utilizadas nos dirigen, a nuestro entender, hacia las teorías lingüísticas del inkling Owen Barfield (1898 – 1997). -

Cweb Study Guide

" " " " " Alice in Wonderland " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " STUDY " GUIDE " " Designed and developed" " " by: Lexi Barnett" " : Meet the Author Lewis Carrol Lewis Carroll was the pseudonym of Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a lecturer in mathematics at Christ Church, Oxford, who lived from 1832 to 1898. Carroll’s physical deformities, partial deafness, and irrepressible stammer made him an unlikely candidate for producing one of the most popular and enduring children’s fantasies in the English language. Carroll’s unusual appearance caused him to behave awkwardly around other adults, and his students at Oxford saw him as a stuffy and boring teacher. Underneath Carroll’s awkward exterior, however, lay a brilliant and imaginative artist. Carroll’s keen grasp of mathematics and logic inspired the linguistic humor and witty wordplay in his stories. Additionally, his unique understanding of children’s minds allowed him to compose imaginative fiction that appealed to young people. In 1856, Carroll and met the Liddell family. During their frequent afternoon boat trips on the river, Carroll told the Liddells fanciful tales. Alice quickly became Carroll’s favorite of the three girls, and he made her the subject of the stories that would later became Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Almost ten years after first meeting the Liddells, Carroll compiled the stories and .1 submitted the completed manuscript for publication. pg If you lived all by yourself,Translating what would your housethe lookJabberwocky! like? Draw your ideal house below: There are many poems recited in Alice in Wonderland- one of the most bizarre is the Jabberwocky! What do you think it means? Write your translation of the words to the right of the poem " ’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. -

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios http://www.litgothic.com/Authors/saki.html Up to now, little has been known about Hector Hugh Munro except that he used the pen name “Saki”; that he wrote a number of witty short stories, two novels, several plays, and a history of Russia; and that he was killed in World War I. His friend Rothay Reynolds published “A Memoir of H. H. Munro” in Saki’s The Toys of Peace (1919), and Munro’s sister Ethel furnished a brief “Biography of Saki” for a posthumous collection of his work entitled The Square Egg and Other Sketches (1924). A. J. Langguth’s Saki is the first full-length biography of the man who, during his brief writing career, published a succession of bright, satirical, and sometimes perfectly crafted short stories that have entertained and amused readers in many countries for well over a half-century. Hector Munro was the third child of Charles Augustus Munro, a British police officer in Burma, and his wife Mary Frances. The children were all born in Burma. Pregnant with her fourth child, Mrs. Munro was brought with the children to live with her husband’s family in England until the child arrived. Frightened by the charge of a runaway cow on a country lane, Mrs. Munro died after a miscarriage. Since the widowed father had to return to Burma, the children — Charles, Ethel, and Hector — were left with their Munro grandmother and her two dominating and mutually antagonistic spinster daughters, Charlotte (“Aunt Tom”) and Augusta. This situation would years later provide incidents, characters, and themes for a number of Hector Munro’s short stories as well as this epitaph for Augusta by Ethel: “A woman of ungovernable temper, of fierce likes and dislikes, imperious, a moral coward, possessing no brains worth speaking of, and a primitive disposition. -

ALICE's ADVENTURES in WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, LA 70001 504-885-2000 www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher’s Notes………………………..…………..…………..……..3 Standards and Benchmarks…………………..……………….…..5 Background………………………………………..…….………………6 Alice’s Adventures, Comparing and Contrasting ………… 12 Art, Math and Set Design: Alice in Minecraft Land...................................................33 The Science of Color Meets the White Rabbit and the March Hare...................74 Additional Resources…………………………………..…..….….106 2 | P a g e Teacher’s Notes Music and Lyrics by Sammy Fain and Bob Hilliard, Oliver Wallace and Cy Coban, Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, Mack David, Al Hoffman and Jerry Livingston Music Adapted and Arranged and Additional Music and Lyrics by Bryan Louiselle Book Adapted and Additional Lyrics by David Simpatico Based on the 1951 Disney film, Alice in Wonderland, and the Lewis Carroll novels, "The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," Lewis Carroll's famous heroine comes to life in this delightful adaptation of the classic Disney film. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of Charles L. Dodgson. Born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury, Cheshire, England, Charles Dodgson wrote and created games as a child. At age 20 he received a studentship at Christ Church and was appointed a lecturer in mathematics. Dodgson was shy but enjoyed creating stories for children. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem,) probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method); some of this work was not published until well after his death. -

The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, the Hunting of the Snark, a Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online

yaTOs (Download pdf) The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online [yaTOs.ebook] The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Pdf Free Lewis Carroll ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1419651 in Books 2011-11-07Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 1.70 x 6.50 x 9.30l, 1.70 #File Name: 0890097003440 pages | File size: 46.Mb Lewis Carroll : The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters): 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Wonderful books for a wonderful priceBy llamapyrLewis Carroll must've been the greatest children's book author of his time. I really admire his writing style and the creativity of his books, having grown up on them since I was 6. I've got a bunch of his novels in hardcover and paperback sitting on my shelves, so it seemed only right to add some digital versions to my library :)Anyway, I came here looking for Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass and found this set, and for a mere 99 cents it seemed worth a look. -

Lewis Carroll: Author, Mathematician, and Christian

Lewis Carroll: Author, Mathematician, and Christian David L. Neuhouser Mathematics Department Taylor University Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), better known as Lewis Carroll, is best known as the creative and imaginative author of the Alice stories, but he was also a mathematician at Christ Church College, Oxford University and a devout Christian. His mathematics, especially mathematical logic, contributed much to the charming “nonsense” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. However, his Christian thought is not evident in those books. In fact, they contain many parodies of morality poems for children. As a result of reading just these books, one might conclude that he was not even interested in morality. But to those who knew him personally, he seemed to be a rather pious, stodgy person. Also, he wrote essays and letters in defense of morality and Christianity as well as books and articles on mathematics. His writings on morality showed little of his literary imagination and his writings on mathematics give no indication of his Christianity. Only in Sylvie and Bruno and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded did Dodgson attempt to bring his literary creativity, mathematics, and Christianity all together in one artistic creation. This paper will attempt to answer the following questions. What motivated him to make this attempt and how successful was it? The Alice stories were the first really successful children’s stories which did not have obvious moral teachings. They were just for fun. However he wrote articles and letters against “indecent literature,” joking about sacred things, and immorality in plays. Some projects that he planned but never completed were: selections from the Bible to be memorized, selections from the Bible with pictures for children, and selections from Shakespeare with inappropriate content for young girls deleted. -

ARTICLE: Jan Susina: Playing Around in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books

Playing Around in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books • Jan Susina Mathematician Charles Dodgson’s love of play and his need for rules came together in his use of popular games as part of the structure of the two famous children’s books, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he wrote under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. The author of this article looks at the interplay between the playing of such games as croquet and cards and the characters and events of the novels and argues that, when reading Carroll (who took a playful approach even in his academic texts), it is helpful to understand games and game play. Charles Dodgson, more widely known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, is perhaps one of the more playful authors of children’s literature. In his career, as a children’s author and as an academic logician and mathematician, and in his personal life, Carroll was obsessed with games and with various forms of play. While some readers are surprised by the seemingly split personality of Charles Dodgson, the serious mathematician, and Lewis Carroll, the imaginative author of children’s books, it was his love of play and games and his need to establish rules and guidelines that effectively govern play that unite these two seemingly disparate facets of Carroll’s personality. Carroll’s two best-known children’s books—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking- Glass and What Alice Found There (1871)—use popular games as part of their structure. In Victoria through the Looking-Glass, Florence Becker Lennon has gone so far as to suggest about Carroll that “his life was a game, even his logic, his mathematics, and his singular ordering of his household and other affairs. -

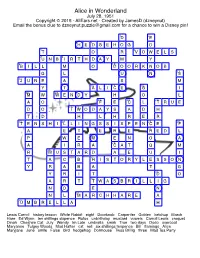

Alice in Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland July 28, 1951 Copyright © 2015 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 2 D E 3 4 H E D G E H O G D 5 6 T O R V O W E L S 7 8 U N B I R T H D A Y M Y 9 10 B I L L M O D O O R K N O B 11 G L U N S 12 J U N E A S M 13 14 15 Y T A L I C E G I 16 17 M W W E N D Y H O L 18 19 20 A O F E C L T R U E 21 22 D O T W O D A Y S A D H T D H L H R E R 23 24 25 26 T E N S H I L L I N G S S I X P E N C E F 27 A E T E R E R E D L 28 P W E M E N O A 29 A I R A C A T Q M 30 R M U S T A R D A E U I 31 T A C B H I S T O R Y L E S S O N Y R A B A T G 32 Y R I T D O 33 A R T T W A S B R I L L I G N O E N 34 N L M A R C H H A R E A 35 U M B R E L L A H Lewis Carroll history lesson White Rabbit eight Doorknob Carpenter Golden ketchup March Hare Ed Wynn ten shillings sixpence Rufus unbirthday mustard vowels Carroll Lewis croquet Dinah Cheshire Cat July Wendy Im Late umbrella smirk True two days Dodo overcoat Maryanne Tulgey Woods Mad Hatter cat red six shillings tenpence Bill flamingo Alice Maryjane June smile False bird hedgehog Dormouse Twas Brillig three Mad Tea Party ★ Thurl Ravenscroft, a member of the singing group, the Mellomen, who sing #27 Across, appears to have lost his head while singing a familiar song in what popular theme park attraction? (2 words) [HAUNTEDMANSION] Across Down 3. -

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland Alice in Wonderland (Movie) (Book) Similarities ______

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Chapter 12 ~ Page 1 © Gay Miller ~ Created by Gay Miller CHAPTER XII. Alice's Evidence 'Here!' cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the heads of the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before. 'Oh, I beg your pardon!' she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, and she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury-box, or they would die. 'The trial cannot proceed,' said the King in a very grave voice, 'until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—all,' he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said do. Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, she had put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. She soon got it out again, and put it right; 'not that it signifies much,' she said to herself; 'I should think it would be quite as much use in the trial one way up as the other.' As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court. -

Annihilating Nihilistic Nonsense Tim Burton Guts Lewis Carroll’S Jabberwocky

Annihilating Nihilistic Nonsense Tim Burton Guts Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky Alice in Wonderland seems to beg for a morbid interpretation. Whether it's Marilyn Manson's "Eat Me, Drink Me," the video game "American McGee's Alice," or Svankmajer's "Alice" and "Jabberwocky," artists love bringing out the darker elements of Alice’s adventures as she wanders among creepy creatures. The 2010 Tim Burton film is the latest twisted adaptation, featuring an older Alice that slays the Jabberwocky. However, unlike the other adaptations, Burton’s adaptation draws most of its grim outlook by gutting Alice in Wonderland of its fundamental core - its nonsense. Alice in Wonderland uses nonsense to liberate, offering frightening amounts of freedom through its playful use of nonsense. However, Burton turns this whimsy into menacing machinations - he pretends to use nonsense for its original liberating purpose but actually uses it for adult plots and preset paths. Burton takes the destructive power of Alice’s insistence for order and amplifies it dramatically, completely removing its original subversive release from societal constraints. Under the façade of paying tribute to Carroll’s whimsical nonsense verse, Burton directly removes nonsense’s anarchic freedom and replaces it with a destructive commitment to sense. This brutal change to both plot and structure turns Alice into a mindless juggernaut, slaying not only the Jabberwock, but also the realm of nonsense, non-linear narrative and real world empires. At first, nonsense in Lewis Carroll’s books seems to just a light-hearted play with language. Even before we come into Wonderland, the idea of nonsense as just a simple child’s diversion is given by the epigraph. -

The Hunting of the Snark: an Agony in Eight Fits Free

FREE THE HUNTING OF THE SNARK: AN AGONY IN EIGHT FITS PDF Lewis Carroll | 100 pages | 15 Apr 2011 | The British Library Publishing Division | 9780712358132 | English | London, United Kingdom The hunting of the snark : an agony in eight fits Landseer, H. Last update: This is a mirrored and modified web edition of a file which originally has been published by eBooks Adelaide. You are free: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work, and to make derivative works under the following conditions: you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the licensor; you may not use this work for commercial purposes; if you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under a license identical to this one. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the licensor. Your fair use and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Please to fancy, if you can, that you are reading a real letter, from a real friend whom you have seen, and whose voice you can seem to yourself to hear wishing you, as I do now with all my heart, a happy Easter. Do you know that delicious dreamy feeling when one first wakes on a summer morning, with the twitter of birds in the air, and the fresh breeze coming in at the open window—when, lying lazily with eyes half shut, one sees as in a dream green boughs waving, or waters rippling in a golden light? It is a pleasure very near to sadness, bringing tears to one's eyes like a beautiful picture or poem. -

Lewis Carroll 'The Jabberwocky'

Lewis Carroll ‘The Jabberwocky’ 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. "Beware the Jabberwock, my son The jaws that bite, the claws that catch! Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun The frumious Bandersnatch!" He took his vorpal sword in hand; Long time the manxome foe he sought— So rested he by the Tumtum tree, And stood awhile in thought. And, as in uffish thought he stood, The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame, Came whiffling through the tulgey wood, And burbled as it came! One, two! One, two! And through and through The vorpal blade went snicker-snack! He left it dead, and with its head He went galumphing back. "And hast thou slain the Jabberwock? Come to my arms, my beamish boy! O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!" He chortled in his joy. 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. Rudyard Kipling ‘The Way Through The Woods’ They shut the road through the woods Seventy years ago. W eather and rain have undone it again, And now you would never know There was once a road through the woods Before they planted the trees. It is underneath the coppice and heath And the thin anemones. Only the keeper sees That, where the ring-dove broods, And the badgers roll at ease, There was once a road through the woods. Yet, if you enter the woods Of a summer evening late, When the night-air cools on the trout-ringed pools Where the otter whistles his mate, (They fear not men in the woods, Because they see so few) You will hear the beat of a horse’s feet, And the swish of a skirt in the dew, Steadily cantering through The misty solitudes, As though they perfectly knew The old lost road through the woods… But there is no road through the woods.