Do Female Mayors Make a Difference? Evidence from Trentino-South Tyrol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31/08/17 TABELLA COM Pagina 1 CODICE DESCRIZIONE CAP

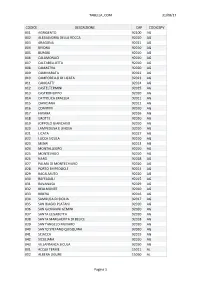

TABELLA_COM 31/08/17 CODICE DESCRIZIONE CAP CODICEPV 001 AGRIGENTO 92100 AG 002 ALESSANDRIA DELLA ROCCA 92010 AG 003 ARAGONA 92021 AG 004 BIVONA 92010 AG 005 BURGIO 92010 AG 006 CALAMONACI 92010 AG 007 CALTABELLOTTA 92010 AG 008 CAMASTRA 92020 AG 009 CAMMARATA 92022 AG 010 CAMPOBELLO DI LICATA 92023 AG 011 CANICATTI' 92024 AG 012 CASTELTERMINI 92025 AG 013 CASTROFILIPPO 92020 AG 014 CATTOLICA ERACLEA 92011 AG 015 CIANCIANA 92012 AG 016 COMITINI 92020 AG 017 FAVARA 92026 AG 018 GROTTE 92020 AG 019 JOPPOLO GIANCAXIO 92010 AG 020 LAMPEDUSA E LINOSA 92010 AG 021 LICATA 92027 AG 022 LUCCA SICULA 92010 AG 023 MENFI 92013 AG 024 MONTALLEGRO 92010 AG 025 MONTEVAGO 92010 AG 026 NARO 92028 AG 027 PALMA DI MONTECHIARO 92020 AG 028 PORTO EMPEDOCLE 92014 AG 029 RACALMUTO 92020 AG 030 RAFFADALI 92015 AG 031 RAVANUSA 92029 AG 032 REALMONTE 92010 AG 033 RIBERA 92016 AG 034 SAMBUCA DI SICILIA 92017 AG 035 SAN BIAGIO PLATANI 92020 AG 036 SAN GIOVANNI GEMINI 92020 AG 037 SANTA ELISABETTA 92020 AG 038 SANTA MARGHERITA DI BELICE 92018 AG 039 SANT'ANGELO MUXARO 92020 AG 040 SANTO STEFANO QUISQUINA 92020 AG 041 SCIACCA 92019 AG 042 SICULIANA 92010 AG 043 VILLAFRANCA SICULA 92020 AG 001 ACQUI TERME 15011 AL 002 ALBERA LIGURE 15060 AL Pagina 1 TABELLA_COM 31/08/17 CODICE DESCRIZIONE CAP CODICEPV 003 ALESSANDRIA 151 AL 004 ALFIANO NATTA 15021 AL 005 ALICE BEL COLLE 15010 AL 006 ALLUVIONI CAMBIO' 15040 AL 007 ALTAVILLA MONFERRATO 15041 AL 008 ALZANO SCRIVIA 15050 AL 009 ARQUATA SCRIVIA 15061 AL 010 AVOLASCA 15050 AL 011 BALZOLA 15031 AL 012 BASALUZZO 15060 AL 013 -

PA Trento - Elenco Comuni N

11-3-2021 GAZZETTA UFFICIALE DELLA REPUBBLICA ITALIANA Serie generale - n. 60 A LLEGATO PA Trento - elenco comuni n. Comuni Note 1 Ala 2 Albiano 3 Aldeno 4 Altavalle 5 Altopiano Della Vigolana 6 Amblar-Don 7 Andalo 8 Arco 9 Avio 10 Baselga Di Pine' 11 Bedollo 12 Besenello 13 Bieno 14 Bleggio Superiore 15 Bocenago 16 Bondone 17 Borgo Chiese 18 Borgo D'Anaunia 19 Borgo Lares 20 Borgo Valsugana 21 Brentonico 22 Bresimo 23 Calceranica Al Lago 24 Caldes 25 Caldonazzo 26 Calliano 27 Campitello Di Fassa — 49 — 11-3-2021 GAZZETTA UFFICIALE DELLA REPUBBLICA ITALIANA Serie generale - n. 60 n. Comuni Note 28 Campodenno 29 Canal San Bovo 30 Canazei 31 Capriana 32 Carisolo 33 Carzano 34 Castel Condino 35 Castel Ivano 36 Castello Tesino 37 Castello-Molina Di Fiemme 38 Castelnuovo 39 Cavalese 40 Cavedago 41 Cavedine 42 Cavizzana 43 Cembra Lisignago 44 Cinte Tesino 45 Cis 46 Civezzano 47 Cles 48 Comano Terme 49 Commezzadura 50 Conta' 51 Croviana 52 Dambel 53 Denno 54 Dimaro Folgarida 55 Drena 56 Dro 57 Fai Della Paganella 58 Fiave' — 50 — 11-3-2021 GAZZETTA UFFICIALE DELLA REPUBBLICA ITALIANA Serie generale - n. 60 n. Comuni Note 59 Fierozzo 60 Folgaria 61 Fornace 62 Frassilongo 63 Garniga Terme 64 Giovo 65 Giustino 66 Grigno 67 Imer 68 Lavarone 69 Lavis 70 Ledro 71 Levico Terme 72 Livo 73 Lona-Lases 74 Luserna 75 Madruzz0 76 Malè 77 Massimeno 78 Mezzana 79 Mezzano 80 Mezzocorona 81 Mezzolombardo 82 Moena 83 Molveno 84 Mori 85 Nago-Torbole 86 Nogaredo 87 Nomi 88 Novaledo 89 Novella — 51 — 11-3-2021 GAZZETTA UFFICIALE DELLA REPUBBLICA ITALIANA Serie generale - n. -

2016Opportunità Commerciali

Opportunità commerciali 2016 Per i tesserati Acli COME OTTENERE LO SCONTO UTILIZZANDO LA TESSERA 1. La tessera è strettamente personale. 2. Per usufruire degli sconti convenuti è necessario esibire una delle seguenti tessere: ACLI, CTA, US ACLI, FAP ACLI, alla cassa del negozio prima della battitura del conto. 3. Non sono accordati sconti sui prodotti in offerta speciale, in vendita promozionale o in caso di saldi di fi ne stagione. 4. Tutti i tesserati sono pregati di segnalare tempestivamente ogni tipo di anomalia derivante dall’uso non corretto delle convenzioni alla Segreteria provinciale delle Acli. 2 Opportunità commerciali 2016 per i tesserati Acli SOMMARIO CATEGORIE CONVENZIONI PLUS 25 ABBIGLIAMENTO 29 ACUSTICa 29 ARREDAMENTI (VEDI MOBILI - ARREDAMENTI) 43 aRTICOLI REGALO (VEDI CASALINGHI - ARTICOLI REGALO) 35 AUTORICAMBI - AUtoaCCESSORI 30 AUtoSCUOLE 31 bIANCHERIA CASA (VEDI TENDAGGI - BIANCHERIA CASA) 53 CALZatURE 31 CARROZZERIE 34 CASALINGHI - ARTICOLI REGALO 35 CENTRI BENESSERE (VEDI ESTETICA - CENTRI BENESSERE) 37 CINEMA (VEDI SPETTACOLI - CINEMA) 51 DENTISTI 35 ERBORISTERIE 36 ESTETICA - CENTRI BENESSERE 37 FERRAMENta 39 FIORI E PIANTE 39 Opportunità commerciali 2016 per i tesserati Acli 3 Foto 40 GIOIELLERIA (VEDI OREFICERIA - GIOIELLERIA) 47 GOMMISTI 40 IMPIANTI / MATERIALI ELETTRICI 41 LIBRERIE 43 mobILI - ARREDAMENTI 43 MUSEI 45 oREFICERIA - GIOIELLERIa 47 ORtopEDIA (VEDI SANITARIA - ORTOPEDIA) 50 ottICA 49 RIStoRANTI 50 SANItaRIA - ORtopEDIa 50 SCUOLA DI LINGUE 50 SPEttaCOLI - CINEma 51 SPORt 53 TENDAGGI - BIANCHERIA CASa 53 TERME 55 TESSUTI 55 TRASLOCHI 55 VINI 57 4 Opportunità commerciali 2016 per i tesserati Acli 2016 Le Acli trentine da 70 anni operano per la solidarietà, la giustizia sociale, la pace, i diritti umani. -

Mountain Bike Con 1 Sola Card, Accedi a Oltre 100 Impianti Estivi E Scopri 12 Aree Vacanza

BIKE FRIENDLY DOLOMITES Strutture ricettive Accommodation Unterkünfte mit speziellen specializzate per i biker, for bikers, Leistungen für Radfahrer: OURS dotate di info corner, kit per with info corner, repair kit for Informationsecke, Werkzeugset für MTB T piccole riparazioni, bike wash e minor fixes, bike washing area kleine Reparaturen, Waschplatz und TOUREN bike room videosorvegliata con and bike deposit with video videoüberwachter Fahrradraum mit MTB allarme (o se in appartamento la surveillance system and alarm Alarmsystem (bei Ferienwohnungen YOUR BIKE I possibilità di portare la bicicletta (or for guests of apartments Möglichkeit das Fahrrad in der EXPERIENCE ITINERAR con voi in alloggio). Possibilità di possibility to take the bycicle Unterkunft abzustellen). Kostenlose escursioni gratuite (o a prezzo inside the facility). Free or oder ermäßigte Touren mit MTB IN THE scontato) con guide MTB oltre che discounted tours with MTB guides Guide sowie Vergünstigungen in DOLOMITES N ad agevolazioni per il noleggio. and special prices in bike rentals. verschiedenen Bike-Verleihen. MOUNTAI BIKE MOENA ADLER FAMILY ALLE ALPI CENTRAL HOTEL MARIA & WELLNESS BEAUT Y & REL AX HHHH GARNI HHHH CLUB RESIDENCE HHHH HHHH RTA Strada de Sèn Pelegrin, 3 Strada de Moene, 67 Strada L. Heilmann , 4 Strada de Sèn Pelegrin, 1 38035 MOENA 38035 MOENA 38035 MOENA 38035 MOENA Tel. +39 0462 574144 Tel. +39 0462 573194 Tel. +39 0462 573228 Tel. +39 0462 573265 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.clubres.com www.hotelallealpi.it www.centralhotel.it www.hotelmaria.com PASSO SAN PELLEGRINO SORAGA DI FASSA SAN GIOVANNI DI FASSA CRISTALLO AVISIO PARK HOTEL RENATO NATURE VAL ACIA HHH S HHHH & WELLNESS RC HHHH HHHH Sèn Pelegrin, 22 Stradon de Fascia, 8 Strada de Solar, 27 - Vigo Strada de Ruf de Ruacia, 42 - Pozza 38035 MOENA 38030 SORAGA DI FASSA 38036 SAN GIOVANNI DI FASSA 38036 SAN GIOVANNI DI FASSA Tel. -

Pay 04.31.00 000 Rsm

Applicativo PAGHE PROJECT Paghe per Aziende, Banche ed Assicurazioni, Enti Pubblici Versione 04.31.00 del 29 Gennaio 2016 Elenco contenuti 1 - Inquadramento territoriale....................................................................................2 Versione 04.31.00 Data rilascio 29/01/2016 Pag. 1 / 3 1 - Inquadramento territoriale 1.1.1 Istituzione di nuovi comuni e comuni estinti dall'01/01/2016 (Da: Dati comuni – Tabelle – Generiche – Inquadramento territoriale) (Da: Dati comuni – Tabelle – ISTAT) Con il presente aggiornamento sono state predisposte le tabelle relative ai nuovi comuni (Città, CAP e ISTAT città) che sostituiscono i comuni estinti (a cui è stato attivato il relativo flag) come da tabella che segue. Elenco nuovi comuni dall'01/01/2016 Elenco comuni estinti sostutuiti dal nuovo comune corrispondente M349 – ALTAVALLE D516 – FAVER E150 – GRAUNO E222 – GRUMES L550 – VALDA M350 – ALTOPIANO DELLA VIGOLANA B078 – BOSENTINO C467 – CENTA SAN NICOLO' L697 – VATTARO L896 – VIGOLO VATTARO M351 – AMBLAR-DON A260 – AMBLAR D336 – DON M352 – BORGO CHIESE B185 – BRIONE C694 – CIMEGO C953 – CONDINO M353 – BORGO LARES A933 – BOLBENO M198 – ZUCLO M354 – CASTEL IVANO I889 – SPERA I979 – STRIGNO L910 – VILLA AGNEDO M355 – CEMBRA LISIGNAGO C452 – CEMBRA E614 – LISIGNAGO M356 – CONTA' D206 – CUNEVO D631 – FLAVON L137 – TERRES M357 – MADRUZZO B386 – CALAVINO E461 – LASINO M358 – PORTE DI RENDENA D250 – DARE' L903 – VIGO RENDENA M006 – VILLA RENDENA M359 – PRIMIERO SAN MARTINO DI CASTROZZA D572 – FIERA DI PRIMIERO I760 – SIROR L201 – TONADICO -

Dipartimento Per Gli Affari Interni E Territoriali Direzione Centrale Dei Servizi Elettorali ______

DIPARTIMENTO PER GLI AFFARI INTERNI E TERRITORIALI DIREZIONE CENTRALE DEI SERVIZI ELETTORALI ___________ Circolare n. 33/2015 Roma, 16 dicembre 2015 AI PREFETTI DELLA REPUBBLICA LORO SEDI AI COMMISSARI DEL GOVERNO NELLE PROVINCE AUTONOME DI TRENTO E BOLZANO AL PRESIDENTE DELLA REGIONE AUTONOMA VALLE D’AOSTA – SERVIZI DI PREFETTURA AOSTA OGGETTO: Rilevazione semestrale e dinamica del corpo elettorale e delle sezioni. Seconda revisione semestrale del 2015 e prima revisione dinamica del 2016. Acquisizione dati. Ai fini della rilevazione in oggetto, si informa che i comuni potranno provvedere, a partire dal 29 dicembre, avvalendosi della procedura informatizzata in rete internet, all’inserimento diretto e invio telematico, mediante compilazione delle maschere informatiche nel frattempo predisposte dallo scrivente Ufficio, dei dati concernenti la seconda revisione semestrale del 2015 (relativa al periodo 1° luglio – 31 dicembre 2015) e la prima revisione dinamica dell’anno successivo (da effettuarsi nel mese di gennaio 2016). Codeste Prefetture provvederanno al controllo e alla validazione dei dati inseriti dai comuni della rispettiva provincia. Per ogni utilità, questa Direzione ha predisposto e messo in rete, anche per il semestre in questione, i corrispondenti nuovi modelli (G-118 e G-DN/118-1) che gli stessi comuni potranno visualizzare ed eventualmente stampare in forma cartacea traendoli dal sito internet di questo Ministero al seguente indirizzo: http://amministratori.interno.it/semestrale/html/modelli.htm. Codeste Prefetture potranno -

Winter News Val Di Fassa

OUTDOOR & MORE ... A PASSO LENTO IL SILENZIO DELLA NEVE FASSA.COM IL PORTALE DELLA TUA VACANZA Mai provato l'esperienza di camminare su Sci ai piedi ma lontano dalle piste, a sentieri innevati, immersi in un ambiente magico ritmo lento con gli sci d'alpinismo o ALLOGGI E OFFERTE VAL DI FASSA TOURIST GUIDE e circondati dal silenzio dei boschi? con le ciaspole, per raggiungere un È ora di vivere una nuova dimensione della rifugio d'alta quota e gustare i piatti VACANZA ATTIVA montagna in inverno , in sicurezza, della tradizione. accompagnati dalle Guide Alpine. METEO E WEBCAM SOCIAL NETWORK SKI MAP NEWSLETTER DOLOMITES MUOVITI CON ATTENZIONE BITTE BEACHTEN SIE MOVE CAREFULLY S WALK NGEN INTER DERU LE NOSTRE W RWAN WINTE ONI GUIDE ALPINE CURSI VACANZA ATTIVA ES RNALI VEA IN I FASS VAL D SEGUICI SU: Guide Alpine Dolomiti Tante altre attività all'aperto come il www.facebook.com/ValdiFassa twitter.com/valdifassa visitvaldifassa guidealpinedolomiti.net parapendio, le escursioni a cavallo, il Guide Alpine Val di Fassa climbing indoor e le fat bike.. scopri guidealpinevaldifassa.it 1 tutte le proposte dello Sport Check 0|2 S Guide Alpine Fassa Guide P oint per una v acanza attiva sulla neve. Monaco Innsbruck 02 COME 320 km 190 km 2 EW fassaguide.com Sport Check Point Passo del Brennero Val Gardena N ARRIVARE Passo Sella Cortina erme Dolomiti R Guida Alpina Luigi Felicetti Strèda Dolomites, 147 - Canazei Passo Pordoi E A RICHIEDI Treviso Venezia T S guidaalpinafelicettiluigi.fassa.com L A C ARTINA! Tel. 0462 870997 www.fassasport.com 170 km S 185 km IN Uscita n. -

Istituti Scolastici 76

13/07/2021 Protocollo Informatico Trentino Tipologia Ente n. Comuni 151 Comunità 15 Pubblica amministrazione locale 12 Società pubbliche strumentali 13 Formazione - Istituti scolastici 76 Musei & Fondazioni 11 Amministrazioni Separate dei beni di Uso 43 Civico (ASUC) Altri Enti 10 TOTALE 331 pag 1 di 12 13/07/2021 Comuni Protocollo Informatico Trentino Comuni Ala Cavedago Moena Albiano Cavedine Molveno Aldeno Cavizzana Mori Altavalle Cembra Lisignago Nogaredo Altopiano della Vigolana Cimone Nomi Amblar Don Cinte Tesino Novaledo Andalo Cis Novella Avio Comano Terme Ossana Baselga di Pinè Commezzadura Palù del Fersina Bedollo Contà Panchià Besenello Croviana Peio Bieno Dambel Pellizzano Bleggio Superiore Denno Pelugo Bocenago Dimaro Folgarida Pergine Valsugana Bondone Fai della Paganella Pieve di Bono - Prezzo Borgo Chiese Fiavè Pieve Tesino Borgo d'Anaunia Fierozzo Pomarolo Borgo Lares Folgaria Porte di Rendena Brentonico Fornace Predaia Bresimo Frassilongo Predazzo Caderzone Terme Garniga Terme Primiero San Martino di Castrozza Calceranica al Lago Giovo Rabbi Caldes Giustino Riva del Garda Caldonazzo Imer Romeno Calliano Isera Roncegno Terme Campitello di Fassa Lavarone Ronchi Valsugana Campodenno Ledro Ronzo-Chienis Canal San Bovo Livo Ronzone Canazei Lona - Lases Roverè della Luna Capriana Luserna Ruffrè - Mendola Carisolo Madruzzo Rumo Carzano Malè Sagnon - Mis Castel Condino Massimeno Samone Castello-Molina di Fiemme Mazzin San Giovanni di Fassa - Sen Jan Castello Tesino Mezzana San Lorenzo Dorsino Castelnuovo Mezzano San Michele all'Adige -

Progetto Banda Ultra Larga in Trentino

PROGETTO BANDA ULTRA LARGA IN TRENTINO La colonna “DATA INIZIO LAVORI PRESUNTA” riporta la data di inizio lavori presunta stimata da Open Fiber sulla base delle tempistiche necessarie per lo svolgimento delle attività di progettazione definitiva ed esecutiva, di approvazione dei progetti e per l'ottenimento dei permessi da parte dei Comuni. Tabella aggiornata al 1 marzo 2019 (1) = Open Fiber non ha ancora definito e comunicato una data di inizio lavori COMUNE 2014 ISTAT COMUNE 2017 ISTAT DATA INIZIO 2014 2017 LAVORI PRESUNTA Ala 22001 giugno 2019 Albiano 22002 (1) Aldeno 22003 (1) Amblar 22004 Amblar-Don 22237 (1) Andalo 22005 (1) Arco 22006 settembre 2018 Avio 22007 maggio 2019 Baselga di Pinè 22009 (1) Bedollo 22011 (1) Bersone 22012 Valdaone 22232 (1) Besenello 22013 (1) Bieno 22015 (1) Bleggio Superiore 22017 ottobre 2019 Bocenago 22018 ottobre 2019 Bolbeno 22019 Borgo Lares 22239 (1) Bondo 22020 Sella Giudicarie 22246 (1) Bondone 22021 ottobre 2019 Borgo Valsugana 22022 (1) Bosentino 22023 Altopiano della Vigolana 22236 (1) Breguzzo 22024 Sella Giudicarie 22246 (1) Brentonico 22025 ottobre 2019 Bresimo 22026 (1) Brez 22027 (1) Brione 22028 Borgo Chiese 22238 (1) Caderzone Terme 22029 (1) Cagnò 22030 (1) Calavino 22031 Madruzzo 22243 giugno 2019 Calceranica al Lago 22032 maggio 2019 Caldes 22033 (1) Caldonazzo 22034 ottobre 2019 Calliano 22035 (1) Campitello di Fassa 22036 (1) Campodenno 22037 (1) Canal San Bovo 22038 (1) Canazei 22039 (1) Capriana 22040 (1) Carano 22041 (1) Carisolo 22042 agosto 2018 Carzano 22043 ottobre 2019 Castel -

Bibliotechecon RITIRO

GRUPPO A ritiro quotidiano, fatti salvi giorni di chiusura e festivi 1 Biblioteca civica piazza Garibaldi 5 38066 RIVA DEL GARDA TN RIVA DEL GARDA TRENTO 2 Biblioteca intercomunale via Marco da Cles 1 38023 CLES TN CLES TRENTO 3 Biblioteca comunale via Roma 40 38061 ALA TN ALA TRENTO 4 Biblioteca di Valle delle Giudicarie esteriori via Prati 1 38077 COMANO TERME TN COMANO TERME TRENTO 5 Biblioteca intercomunale via Filos 2 38017 MEZZOLOMBARDO TN MEZZOLOMBARDO TRENTO 6 Biblioteca intercomunale via Damiano Chiesa 1 38079 TIONE DI TRENTO TN TIONE DI TRENTO TRENTO 7 Biblioteca intercomunale via Fiume 6 38054 FIERA DI PRIMIERO TN FIERA DI PRIMIERO TRENTO 8 Biblioteca civica corso Bettini 43 38068 ROVERETO TN ROVERETO TRENTO 9 Biblioteca intercomunale piazzetta degli Alpini 8 38015 LAVIS TN LAVIS TRENTO 10 Biblioteca intercomunale via al Sole 30 38068 PINZOLO TN PINZOLO TRENTO 11 Biblioteca intercomunale Altopiano Paganella-Brenta piazzale Paganella 3 38010 ANDALO TN ANDALO TRENTO 12 Biblioteca comunale Via Degasperi 12 38037 PREDAZZO TN PREDAZZO TRENTO 13 Biblioteca intercomunale via Marconi 8 38033 CAVALESE TN CAVALESE TRENTO 14 Biblioteca intercomunale via Barbacovi 4 38010 PREDAIA TAIO TN PREDAIA TAIO TRENTO 15 Biblioteca comunale via della Conciliazione 5 38089 STORO TN STORO TRENTO 16 Biblioteca Valle di Cavedine via don Negri 30 38073 CAVEDINE TN CAVEDINE TRENTO 17 Biblioteca comunale via Battisti 14 38074 DRO TN DRO TRENTO 18 Biblioteca comunale via del 26 Maggio 10 38042 BASELGA DI PINÉ TN BASELGA DI PINE' TRENTO 19 Biblioteca intercomunale piazza Madonna della Pace 12 38025 DIMARO FOLGARIDA TN DIMARO FOLGARIDA TRENTO 20 Biblioteca comunale piazza Serra 11 38057 PERGINE VALSUGANA TN PERGINE VALSUGANA TRENTO 21 Biblioteca comunale via Marconi 6 38056 LEVICO TERME TN LEVICO TERME TRENTO 22 BCT. -

REPUBBLICA ITALIANA in NOME DEL POPOLO ITALIANO Corte Dei

Decisione n. 2/PARI/2018 REPUBBLICA ITALIANA IN NOME DEL POPOLO ITALIANO Corte dei conti Sezioni riunite per la regione Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol Presiedute dal Presidente Josef Hermann RÖSSLER e composte dai Magistrati: Anna Maria Rita LENTINI Presidente di Sezione Irene THOMASETH Consigliere Alessandro PALLAORO Consigliere Tullio FERRARI Consigliere Massimo AGLIOCCHI Primo Referendario Alessia DI GREGORIO Primo Referendario ha pronunciato la seguente DECISIONE nel giudizio di parificazione sul rendiconto generale della Regione Autonoma Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol per l’esercizio finanziario 2017; VISTI gli articoli 100, secondo comma, e 103, secondo comma, della Costituzione; VISTO il testo unico delle leggi costituzionali concernenti lo Statuto speciale per il Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, approvato con decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 31 agosto 1972, n. 670 e relative norme di attuazione; VISTO il decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 15 luglio 1988, n. 305, e successive modifiche ed integrazioni, recante norme di attuazione dello Statuto speciale per la Regione Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol per l’istituzione delle Sezioni di controllo della Corte dei conti di Trento e di Bolzano e per il personale ad esse addetto; VISTO il testo unico delle leggi sull’ordinamento della Corte dei conti, approvato con regio decreto 12 luglio 1934, n. 1214 e successive modifiche ed integrazioni; 1 VISTA la legge 14 gennaio 1994, n. 20, recante disposizioni in materia di giurisdizione e controllo della Corte dei conti e successive modifiche ed integrazioni; VISTO il decreto legislativo 23 giugno 2011, n. 118, recante disposizioni in materia di armonizzazione dei sistemi contabili e degli schemi di bilancio delle regioni, degli enti locali e dei loro organismi, a norma degli artt. -

Tipologia Ente N. Comuni 158 Comunità 15 Pubblica Amministrazione Locale 10 Società Pubbliche Strumentali 14 Formazione

30/04/2019 Protocollo Informatico Trentino Tipologia Ente n. Comuni 158 Comunità 15 Pubblica amministrazione locale 10 Società pubbliche strumentali 14 Formazione - Istituti scolastici 74 Musei & Fondazioni 11 Amministrazioni Separate dei beni di Uso 43 Civico (ASUC) Altri Enti 5 TOTALE 330 pag 1 di 10 30/04/2019 Comuni Protocollo Informatico Trentino Comuni Ala Cavizzana Nogaredo Sporminore Albiano Cembra Lisignago Nomi Stenico Aldeno Cimone Novaledo Storo Altavalle Cinte Tesino Ossana Strembo Andalo Cis Palù del Fersina Telve Altopiano della Vigolana Cloz Panchià Telve di Sopra Amblar Don Commezzadura Peio Tenna Avio Contà Pellizzano Tenno Baselga di Pinè Croviana Pelugo Terragnolo Bedollo Daiano Pieve di Bono - Prezzo Terre d'Adige Besenello Dambel Pieve Tesino Terzolas Bieno Denno Pomarolo Tesero Bleggio Superiore Dimaro Folgarida Porte di Rendena Tione di Trento Bocenago Faedo Predaia Ton Bondone Fai della Paganella Predazzo Torcegno Borgo Chiese Fiavè Primiero San Martino di Castrozza Trambileno Borgo Lares Fierozzo Rabbi Tre Ville Brentonico Folgaria Revò Trento Bresimo Fondo Riva del Garda Valdaone Brez Fornace Romallo Valfloriana Caderzone Terme Frassilongo Romeno Vallarsa Cagnò Garniga Terme Roncegno Terme Vallelaghi Calceranica al Lago Giovo Ronchi Valsugana Varena Caldes Giustino Ronzo-Chienis Vermiglio Caldonazzo Imer Ronzone Vignola Falesina Calliano Isera Roverè della Luna Villa Lagarina Canazei Lavarone Ruffrè - Mendola Ville d'Anaunia Castello-Molina di Fiemme Ledro Rumo Volano Comano Terme Livo Sagnon - Mis Ziano di Fiemme