'Tremble, Britannia!': Fear, Providence and the Abolition of the Slave Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Church Missionary Society", by E

Durham E-Theses The voluntary principle in education: the contribution to English education made by the Clapham sect and its allies and the continuance of evangelical endeavour by Lord Shaftesbury Wright, W. H. How to cite: Wright, W. H. (1964) The voluntary principle in education: the contribution to English education made by the Clapham sect and its allies and the continuance of evangelical endeavour by Lord Shaftesbury, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9922/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE VOLUNTARY PRINCIPLE IN EDUCATION: THE CONTRIBUTION TO ENGLISH EDUCATION MADE BY THE CLAPHAil SECT AND ITS ALLIES AM) THE CONTINUAi^^CE OP EVANGELICAL EI-JDEAVOUR BY LORD SHAFTESBURY. A thesis for the degree of MoEd., by H. T7right, B.A. Table of Contents Chapter 1 The Evangelical Revival -

Magdalene College Magazine 2019-20

magdalene college magdalene magdalene college magazine magazine No 63 No 64 2018–19 2019 –20 M A G D A L E N E C O L L E G E The Fellowship, October 2020 THE GOVERNING BODY 2020 MASTER: Sir Christopher Greenwood, GBE, CMG, QC, MA, LLB (1978: Fellow) 1987 PRESIDENT: M E J Hughes, MA, PhD, Pepys Librarian, Director of Studies and University Affiliated Lecturer in English 1981 M A Carpenter, ScD, Professor of Mineralogy and Mineral Physics 1984 J R Patterson, MA, PhD, Praelector, Director of Studies in Classics and USL in Ancient History 1989 T Spencer, MA, PhD, Director of Studies in Geography and Professor of Coastal Dynamics 1990 B J Burchell, MA and PhD (Warwick), Joint Director of Studies in Human, Social and Political Sciences and Professor in the Social Sciences 1990 S Martin, MA, PhD, Senior Tutor, Admissions Tutor (Undergraduates), Joint Director of Studies and University Affiliated Lecturer in Mathematics 1992 K Patel, MA, MSc and PhD (Essex), Director of Studies in Land Economy and UL in Property Finance 1993 T N Harper, MA, PhD, College Lecturer in History and Professor of Southeast Asian History (1990: Research Fellow) 1994 N G Jones, MA, LLM, PhD, Director of Studies in Law (Tripos) and Reader in English Legal History 1995 H Babinsky, MA and PhD (Cranfield), Tutorial Adviser (Undergraduates), Joint Director of Studies in Engineering and Professor of Aerodynamics 1996 P Dupree, MA, PhD, Tutor for Postgraduate Students, Joint Director of Studies in Natural Sciences and Professor of Biochemistry 1998 S K F Stoddart, MA, PhD, Director -

Magdalene College Magazine 2017-18

magdalene college magdalene magdalene college magazine magazine No 62 No 62 2017–18 2017 –18 Designed and printed by The Lavenham Press. www.lavenhampress.co.uk MAGDALENE COLLEGE The Fellowship, October 2018 THE GOVERNING BODY 2013 MASTER: The Rt Revd & Rt Hon the Lord Williams of Oystermouth, PC, DD, Hon DCL (Oxford), FBA 1987 PRESIDENT: M E J Hughes, MA, PhD, Pepys Librarian, Director of Studies and University Affiliated Lecturer in English 1981 M A Carpenter, ScD, Professor of Mineralogy and Mineral Physics 1984 H A Chase, ScD, FREng, Director of Studies in Chemical Engineering and Emeritus Professor of Biochemical Engineering 1984 J R Patterson, MA, PhD, Praelector, Director of Studies in Classics and USL in Ancient History 1989 T Spencer, MA, PhD, Director of Studies in Geography and Professor of Coastal Dynamics 1990 B J Burchell, MA, and PhD (Warwick), Tutor, Joint Director of Studies in Human, Social and Political Science and Reader in Sociology 1990 S Martin, MA, PhD, Senior Tutor, Admissions Tutor (Undergraduates), Director of Studies and University Affiliated Lecturer in Mathematics 1992 K Patel, MA, MSc and PhD (Essex), Director of Studies in Economics & in Land Economy and UL in Property Finance 1993 T N Harper, MA, PhD, College Lecturer in History and Professor of Southeast Asian History (1990: Research Fellow) 1994 N G Jones, MA, LLM, PhD, Dean, Director of Studies in Law and Reader in English Legal History 1995 H Babinsky, MA and PhD (Cranfield), College Lecturer in Engineering and Professor of Aerodynamics 1996 P Dupree, -

* Earlier Life-Truth'- Exponents

2 tm r « / ■ *. ^ . • •••■ i * * EARLIER LIFE-TRUTH'- % * : . # EXPONENTS ■ r» V ■ • I" * a : Tv • ? ■ 33T Church of God General Conference: McDonough, GA, https://coggc.org/ A. J. MILLS. • • r. * WITH FOREWORD BY ROBERT K. STRANG, m % Editor of Words of Life. a % • price 15 Cents. .* ■ * •- • : NATIONAL BIBLE INSTITUTION OREGON, ILLINOIS. ■*% *#.. V •« CANADA: R. H. JUDD, GRAFTON, ONTARIO. I' LONDON: * ELLIOT STOCK, 7, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.4. MCMXXV !:■ I % % Church of God General Conference: McDonough, GA, https://coggc.org/ EARLIER LIFE-TRUTH EXPONENTS BY Church of God General Conference: McDonough, GA, https://coggc.org/ A. J. MILLS. WITH FOREWORD BY ROBERT K. STRANG, Editor of Words of Life. price 15 Cents. NATIONAL BIBLE INSTITUTION OREGON, ILLINOIS. CANADA: R. II. JUDD, GRAFTON, ONTARIO. LONDON: ELLIOT STOCK, 7, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.4. MCMXXV Church of God General Conference: McDonough, GA, https://coggc.org/ EARLIER LIFE-TRUTH EXPONENTS. By A. J. MILLS, Thames Ditton. [Reprinted from 'Words of Life."] I. It is proposed, in the following pages, to give, in brief outline, what may be known of earlier life-truth exponents, whose works and testimony remain to this day. It is generally recognized that the doctrine now known as Conditional Immortality is by no means modern, those who hold the teaching affirming that, as far back in history as Gen. ii. and iii, the conditions were laid down under which man, if he had continued in obedience, might have remained in life and being. ChurchPassing of God Generalon from Conference:that McDonough,remote GA, https://coggc.org/period, there is ample evidence in the Scriptures that life, continuous, permanent life, would only be given to man upon the fulfilment of certain conditions. -

1934 Unitarian Movement.Pdf

fi * " >, -,$a a ri 7 'I * as- h1in-g & t!estP; ton BrLLnch," LONDON t,. GEORGE ALLEN &' UNWIN- LID v- ' MUSEUM STREET FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1934 ACE * i& ITwas by invitation of The Hibbert Trustees, to whom all interested in "Christianity in its most simple and intel- indebted, that what follows lieibleV form" have long been was written. For the opinions expressed the writer alone is responsible. His aim has been to give some account of the work during two centuries of a small group of religious thinkers, who, for the most part, have been overlooked in the records of English religious life, and so rescue from obscurity a few names that deserve to be remembered amongst pioneers and pathfinders in more fields than one. Obligations are gratefully acknowledged to the Rev. V. D. Davis. B.A., and the Rev. W. H. Burgess, M.A., for a few fruitful suggestions, and to the Rev. W. Whitaker, I M.A., for his labours in correcting proofs. MANCHESTER October 14, 1933 At1 yigifs ~ese~vcd 1L' PRENTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY UNWIN BROTHERS LTD., WOKING CON TENTS A 7.. I. BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP' PAGE BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP 1 3 iI. EDUCATION CONFORMIST ACADEMIES 111. THE MODERN UNIVERSITIES 111. JOURNALS AND WRIODICAL LITERATURE . THE UNITARIAN CONTRIBUTI:ON TO PERIODICAL . LITERATURE ?aEz . AND BIOGR AND BELLES-LETTRES 11. PHILOSOPHY 111. HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY I IV. LITERATURE ....:'. INDEX OF PERIODICALS "INDEX OF PERSONS p - INDEX OF PLACES :>$ ';: GENERAL INDEX C. A* - CHAPTER l BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP 9L * KING of the origin of Unitarian Christianity in this country, -

Vol. 57 No. 4 APRIL 1952 Threepence Notes of the Month

vol. 57 No. 4 APRIL 1952 Threepence Notes of the Month Custos The Story of South Place—III What is Existentialism? Hector flawton Man and Nature II'. E. Swinton Some Problems of Party Politics Lord Chorley Science and the Social Process D. U,. Macrae The Problem of Humour Professor J. C. Hugel Correspondence South Place News Society's Activities S_OLITH PLA'CE ETHICAL SOCIETY SUNDAY MORNIING MEETINGS AT ELEVEN O'CLOCK April 6—ARCHIBALD ROBERTSON, M.A.—"The Ethics of Belief" Bass Solos by G. C. DoNvaty: Loveliest of Trees Somervell Pilgrim's Song Tschaikowsky Hymn: No. 1 - April I3—EASTER—CLOSED April 20—S. K. RATCLIFFE—"H. G. Wells a Revaluation" ' Piano Solo by ARVON DAVIES : Sonata in F sharp. Op. 78 .. .. Beethoven Hymn: No. 11 • April 27—JOSEPH McCABE—"History and its Pessimists" Violin and Piano by MAROOF MACDHRION and FREDERIC JACKSON: Sonatina . Dvorak Hymn: No. 46 (Tune 212) QUESTIONS AFTER THE LECTURE Admission Free Collection SOUTH PLACE SUNDAY CONCERTS, 61s1 SEASON Concerts 6.30 p.m. (Doors open 6.0 p.m.) Admission Is. April 6—MACG1BBON STRING QUARTET Beethoven in F. Op. IS, No. I : Haydn in G. Op 77, No. I : Dohnanyi in p flat, Op 15. April 13—NO CONCERT April 20—LONDON HARPSICHORD ENSEMBLE Bach Flute Sonata in E, Trio in C minor from The Musical Offering, W. F. Bach flute trio in D; Sammartini 'cello and harpsichord Sonata in G ; Handel violin and harpsichord Sonata in A; Haydn flute trio in C minor; Murrill Suite Française for - harpsichord. April 27—CONCERT IN AID OF THE MUSICIANS' BENEVOLENT EUNI). -

Fine Books, Manuscripts, Atlases & Historical Photographs

Fine Books, Manuscripts, Atlases & Historical Photographs Montpelier Street, London I 4 December 2019 Fine Books, Manuscripts, Atlases & Historical Photographs Montpelier Street, London | Wednesday 4 December 2019, at 11am BONHAMS ENQUIRIES Please see page 2 for bidder REGISTRATION Montpelier Street Matthew Haley information including after-sale IMPORTANT NOTICE Knightsbridge Simon Roberts collection and shipment. Please note that all customers, London SW7 1HH Luke Batterham irrespective of any previous activity www.bonhams.com Sarah Lindberg Please see back of catalogue with Bonhams, are required to +44 (0) 20 7393 3828 for important notice to bidders complete the Bidder Registration VIEWING +44 (0) 20 7393 3831 Form in advance of the sale. The ILLUSTRATIONS Sunday 1 December [email protected] form can be found at the back of 11am to 3pm Front cover: Lot 145 every catalogue and on our Monday 2 December Shipping and Collections Back cover: Lot 347 website at www.bonhams.com 9am to 4.30pm Joel Chandler and should be returned by email or Tuesday 3 December +44 (0)20 7393 3841 post to the specialist department 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] or to the bids department at Wednesday 4 December [email protected] 9am to 11am PRESS ENQUIRIES To bid live online and / or [email protected] leave internet bids please go to BIDS www.bonhams.com/auctions/25356 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 CUSTOMER SERVICES and click on the Register to bid link +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Monday to Friday at the top left of the page. [email protected] 8.30am to 6pm To bid via the internet +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 please visit www.bonhams.com LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS New bidders must also provide AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE proof of identity when submitting bids. -

Romanticism and the Letter Edited by Madeleine Callaghan · Anthony Howe Palgrave Studies in the Enlightenment, Romanticism and Cultures of Print

PALGRAVE STUDIES IN THE ENLIGHTENMENT, ROMANTICISM AND CULTURES OF PRINT Romanticism and the Letter Edited by Madeleine Callaghan · Anthony Howe Palgrave Studies in the Enlightenment, Romanticism and Cultures of Print Series Editors Anne K. Mellor Department of English University of California Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA, USA Clifford Siskin Department of English New York University New York, NY, USA Palgrave Studies in the Enlightenment, Romanticism and Cultures of Print features work that does not fit comfortably within established boundaries – whether between periods or between disciplines. Uniquely, it combines efforts to engage the power and materiality of print with explorations of gender, race, and class. By attending as well to intersec- tions of literature with the visual arts, medicine, law, and science, the series enables a large-scale rethinking of the origins of modernity. Editorial Board: Isobel Armstrong, Birkbeck College, University of London, UK; John Bender, Stanford University, USA; Alan Bewell, University of Toronto, Canada; Peter de Bolla, University of Cambridge, UK; Robert Miles, University of Victoria, Canada; Claudia Johnson, Princeton University, USA; Saree Makdisi, UCLA, USA; Felicity A Nussbaum, UCLA, USA; Mary Poovey, New York University, USA; Janet Todd, University of Cambridge, UK. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14588 Madeleine Callaghan • Anthony Howe Editors Romanticism and the Letter Editors Madeleine Callaghan Anthony Howe University of Sheffield Birmingham City University Sheffield, UK Birmingham, UK Palgrave Studies in the Enlightenment, Romanticism and Cultures of Print ISBN 978-3-030-29309-3 ISBN 978-3-030-29310-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29310-9 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. -

THE VIOLA DA GAMBA SOCIETY JOURNAL General Editor: Andrew Ashbee

The Viola da Gamba Society Journal Volume One (2007) The Viola da Gamba Society of Great Britain 2006-7 PRESIDENT Alison Crum CHAIRMAN Michael Fleming COMMITTEE Elected Members: Michael Fleming, Robin Adams, Alison Kinder Ex Officio Members: Caroline Wood, Stephen Pegler, Mary Iden Co-opted Members: Alison Crum, Nigel Stanton. Jacqui Robertson-Wade ADMINISTRATOR Caroline Wood 56 Hunters Way, Dringhouses, York YO24 1JJ tel/fax: 01904 706959 [email protected] THE VIOLA DA GAMBA SOCIETY JOURNAL General Editor: Andrew Ashbee Editor of Volume 1 (2007): Andrew Ashbee: 214 Malling Road, Snodland, Kent ME6 5EQ [email protected] Editor of Volume 2 (2008): Professor Peter Holman: School of Music, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT [email protected] Full details of the Society’s officers and activities, and information about membership, can be obtained from the Administrator. Contributions for The Viola da Gamba Society Journal, which may be about any topic related to early bowed string instruments and their music, are always welcome, though potential authors are asked to contact the editor at an early stage in the preparation of their articles. Finished material should preferably be submitted on IBM format 3.5 inch floppy disc (or by e-mail) as well as in hard copy. A style guide will be prepared. In the meantime current examples should suffice, together with instructions from the general editor. ii CONTENTS Editorial iv Manuscripts of Consort Music in London, c.1600-1625: some Observations—ANDREW ASHBEE 1 Continuity and Change in English Bass Viol Music: the Case of Fitzwilliam Mu. -

Radicalism, Rational Dissent, and Reform : the Pla- Tonised Interpretation of Psychological Androgyny and the Unsexed Mind in England in the Romantic Era

BIROn - Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Radicalism, rational dissent, and reform : the Pla- tonised interpretation of psychological androgyny and the unsexed mind in England in the Romantic era https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/44948/ Version: Citation: Russell, Victoria Fleur (2019) Radicalism, rational dissent, and reform : the Platonised interpretation of psychological androgyny and the unsexed mind in England in the Romantic era. [Thesis] (Unpub- lished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through BIROn is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Radicalism, Rational Dissent, and Reform: The Platonised Interpretation of Psychological Androgyny and the Unsexed Mind in England in the Romantic Era. Victoria Fleur Russell Department of History, Classics & Archaeology Birkbeck, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) September 2017 1 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Victoria Fleur Russell 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the Platonised concept of psychological androgyny that emerged on the radical margins of Rational Dissent in England between the 1790s and the 1840s. A legacy largely of the socio-political and religious impediments experienced by Rational Dissenters in particular and an offshoot of natural rights theorising, belief in the unsexed mind at this time appears more prevalent amongst radicals in England than elsewhere in Britain. Studied largely by scholars of Romanticism as an aesthetic concept associated with male Romantics, the influence of the unsexed mind as a notion of psycho-sexual equality in English radical discourse remains largely neglected in the historiography. -

The Tenacity of Bondage: an Anthropological History of Slavery

The Tenacity of Bondage: An Anthropological History of Slavery and Unfree Labor in Sierra Leone by Ian David Stewart A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paul C. Johnson, Co-Chair Associate Professor Kelly M. Askew, Co-Chair Professor Albert C. Cain Professor Elisha P. Renne © Ian David Stewart 2013 Por Mi Amor, my editor, my partner, my love. Without you this dream would never have happened. ii Acknowledgements This project was born as a series of news articles written in the 1990s. Along the way to becoming a doctoral dissertation it has, by necessity, been transformed and reconfigured; first into essays and articles and then into chapters. I am grateful for the support and encouragement from so many people along the way. It was these people who saw the value and import of my scholarship, not just in the classroom, but in the larger world where human rights—particularly the rights of children—are increasingly in peril, and labor conditions in many parts of the world are slowly moving back toward the exploitive arrangements of slave and master. To thank and acknowledge everyone who played a part in helping me bring this project to fruition would require a chapter unto itself. However there are numerous key people I would like to identify and thank for their belief in me and this project. In Sierra Leone, I am indebted to the hard work, assistance and patience of my journalist colleague Clarence Roy-Macaulay, and Corinne Dufka, who, as photojournalist-turned human rights researcher knows better than most the realities of child soldiery in the Mano River Region. -

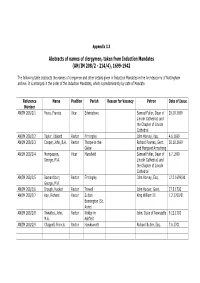

Appendix 3-3.Pdf

Appendix 3.3 Abstracts of names of clergymen, taken from Induction Mandates (AN/IM 208/2 - 214/4), 1699-1942 The following table abstracts the names of clergymen and other details given in Induction Mandates in the Archdeaconry of Nottingham archive. It is arranged in the order of the Induction Mandates, which is predominantly by date of Mandate. Reference Name Position Parish Reason for Vacancy Patron Date of Issue Number AN/IM 208/2/1 Peete, Francis Vicar Edwinstowe Samuel Fuller, Dean of 26.10.1699 Lincoln Cathedral, and the Chapter of Lincoln Cathedral AN/IM 208/2/2 Taylor, Edward Rector Finningley John Harvey, Esq. 4.6.1699 AN/IM 208/2/3 Cooper, John, B.A. Rector Thorpe-in-the- Richard Fownes, Gent. 30.10.1699 Glebe and Margaret Armstrong AN/IM 208/2/4 Mompesson, Vicar Mansfield Samuel Fuller, Dean of 6.7.1699 George, M.A. Lincoln Cathedral, and the Chapter of Lincoln Cathedral AN/IM 208/2/5 Barnardiston, Rector Finningley John Harvey, Esq. 12.2.1699/00 George, M.A. AN/IM 208/2/6 Brough, Hacker Rector Trowell John Hacker, Gent. 27.5.1700 AN/IM 208/2/7 Kay, Richard Rector Sutton King William III 7.2.1700/01 Bonnington (St. Anne) AN/IM 208/2/8 Thwaites, John, Rector Kirkby-in- John, Duke of Newcastle 9.12.1700 M.A. Ashfield AN/IM 208/2/9 Chappell, Francis Rector Hawksworth Richard Butler, Esq. 7.6.1701 Reference Name Position Parish Reason for Vacancy Patron Date of Issue Number AN/IM 208/2/10 Caiton, William, Vicar Flintham Death of Simon Richard Bentley, Master 15.6.1701 M.A.