Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2018 Celebrating Our 45Th

Celebrating our 45th Anniversary, p. 2 Stowe Restoration Project, pgs. 3-4 The Trevelyans of Wallington Hall, pgs. 5-6 Spring 2018 1 | From the Executive Director Dear Members & Friends, THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION 20 West 44th Street, Suite 606 New York, New York 10036-6603 2018 marks Royal Oak’s 45th Anniversary. We Churchill’s studio at Chartwell give tangible 212.480.2889 | www.royal-oak.org will celebrate this in many ways—more with a expression to the many new interpretive focus on where we are as an organization today programs that will excite visitors daily just as and what we hope for in the future. the exhibition did 35 years ago. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Honorary Chairman In reviewing some of the histories of Royal Other big news for 2018 is our appeal to help Mrs. Henry J. Heinz II Oak, I was surprised to find an event in 1983 the National Trust finish off a multi-year and Chairman that was noted as pivotal in transforming multi-task restoration effort for Stowe. Stowe Lynne L. Rickabaugh the Foundation’s relationship is one of the leading garden and Vice Chairman with the Trust from one of just landscape properties in England Prof. Susan S. Samuelson growing ‘friendship’ to one of a and has a wide significance in Treasurer serious fundraising partnership. the history of garden design in Renee Nichols Tucei The connections of this historic Europe, Russia and America (see Secretary event with what Royal Oak has pages 3-4). It is among the most Thomas M. Kelly more recently accomplished and visited Trust properties. -

Some Pages from the Book

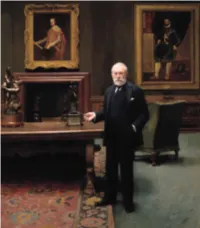

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

Renegotiating Linguistic Identities in the Wake of Globalization

European Scientific Journal June 2015 /SPECIAL/ edition ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 RENEGOTIATING LINGUISTIC IDENTITIES IN THE WAKE OF GLOBALIZATION Pallavi Nimbalwar Navrachana University, School of Environmental Design and Architecture, Vadodara, Gujarat, India Abstract Globalization, as a world phenomenon has a direct relationship with language identities, Language loss and their chances of survival. Also, with English hailed as the lingua franca and a language for possibilities and prosperity, more and more world citizens are drawn towards it, often at the cost of their native languages. While it is true that we are all staunchly moving towards one world and language uniformity ensures homogenization, yet it clashes with the principle of preserving linguistic diversity. This poses certain questions like how is the globalization phenomenon related to issues of languages, culture and identity. What will be the effect of language loss; what roles does the linguist have to play in the process of language survival; why is language preservation needed? This paper scrutinizes language specific issues in the wake of globalization. The issues dealt with here are: status of world language and their chances of survival; factors contributing towards language loss and language survival; effects of language loss and need for language preservation; suggested steps towards language preservation. Keywords: Globalization, Language Homogenization, Lingua Franca, Language shift, Language Survival, Language, Culture and Identity, Language Preservation Paper Globalization, is certainly not a new phenomenon, yet, never before it was so fast paced as it is today. Advances in technology and telecommunication have contributed majorly towards furthering economic and cultural interdependence and have greatly paced up the globalization phenomenon. -

American Behavioral Scientist

American Behavioral Scientist http://abs.sagepub.com/ What Is Islamophobia and How Much Is There? Theorizing and Measuring an Emerging Comparative Concept Erik Bleich American Behavioral Scientist 2011 55: 1581 originally published online 26 September 2011 DOI: 10.1177/0002764211409387 The online version of this article can be found at: http://abs.sagepub.com/content/55/12/1581 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for American Behavioral Scientist can be found at: Email Alerts: http://abs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://abs.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://abs.sagepub.com/content/55/12/1581.refs.html >> Version of Record - Nov 14, 2011 Proof - Sep 26, 2011 What is This? Downloaded from abs.sagepub.com at MIDDLEBURY COLLEGE LIBRARY on November 28, 2011 7ABS40938ABS Article American Behavioral Scientist 55(12) 1581 –1600 What Is Islamophobia © 2011 SAGE Publications Reprints and permission: http://www. and How Much Is sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0002764211409387 There? Theorizing and http://abs.sagepub.com Measuring an Emerging Comparative Concept Erik Bleich1 Abstract Islamophobia is an emerging comparative concept in the social sciences. Yet there is no widely accepted definition of Islamophobia that permits systematic comparative and causal analysis. This article explores how the term Islamophobia has been deployed in public and scholarly debates, emphasizing that these discussions have taken place on multiple registers. It then draws on research on concept formation, prejudice, and analogous forms of status hierarchies to offer a usable social scientific definition of Islamophobia as indiscriminate negative attitudes or emotions directed at Islam or Muslims. -

Rethinking Islamophobia: Myth Or Reality

Azrul Azlan Abdul Rahman. (2018). Rethinking Islamophobia: Myth or Reality. Idealogy, 3(2) : 91-99, 2018 Rethinking Islamophobia: Myth or Reality Azrul Azlan Abdul Rahman Fakulti Pengajian & Pengurusan Pertahanan Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia, Kem Sungai Besi, 57000 Kuala Lumpur, [email protected] Abstract. Does Islamophobia really exist? Or is the hatred and abuse of Muslims being exaggerated to suit politicians' needs and silence the critics of Islam? The trouble with Islamophobia is that it is an irrational concept. It confuses hatred of, and discrimination against, Muslims on the one hand with criticism of Islam on the other. The charge of 'Islamophobia' is all too often used not to highlight racism but to stifle criticism. Islamophobia can generally be defined as unfounded fear of and hostility towards Islam. Such fear and hostility leads to discrimination against Muslim, exclusion of Muslim from mainstream political or social process, stereotyping, the presumption of guilt by association and hate crimes. This paper focuses on terrorism, and to be more precise, the issue of Islamophobia because of the misperception towards Islam. These issues become even more crucial when such phobia has led to a stress among the world community. People need to understand what Islam really meant, so that they would be clear that they cannot judge Islam by looking at the Muslim itself. Thus, the question arises whether the idea of ‘Islamophobia’ is a myth, or a reality? Keyword : Islamophobia, Propaganda, Islam 91 Introduction As the United Nations general assembly gets underway in New York, a push is on by the 57–member-country Organisation of Islamic Co-operation to make blasphemy an international criminal offence. -

Theology and Society in Three Cities: Berlin, Oxford and Chicago, 1800–1914 (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2014), By

Edinburgh Research Explorer Theology and Society in Three Cities: Berlin, Oxford and Chicago, 1800–1914 (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2014), by Mark D. Chapman Citation for published version: Purvis, Z 2016, 'Theology and Society in Three Cities: Berlin, Oxford and Chicago, 1800–1914 (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2014), by Mark D. Chapman', Journal of Anglican Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 109–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740355315000133 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S1740355315000133 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Anglican Studies General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Journal of Anglican Studies Mark D. Chapman, Theology and Society in Three Cities: Berlin, Oxford and Chicago, 1800– 1914 (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2014), pp. 152 (paperback), ISBN 978-0-227-67989- 0. This is an important, concise book, deserving of a wide readership. Originally appearing in the form of the Hensley Henson lectures at the University of Oxford, delivered in early 2013, its astute analysis of three national contexts and explorations of how ‘external’ political and cultural climates can and do feed Christian reflection in sometimes surprisingly different ways should help to reinvigorate research into the history of modern theology. -

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

Victorious Century: the United Kingdom 1800-1906 by David Cannadine Published in 2017

Welcome to our March book, Historians! Our next meeting is Tuesday, March 3 at 6:30. That is Super Tuesday so if you are planning to vote in the primaries, just remember to vote early. We will discuss Victorious Century: The United Kingdom 1800-1906 by David Cannadine published in 2017. Sir David Cannadine is the Dodge Professor of History at Princeton and this book is, in many ways, the overview of 19th c. British history that history students no longer seem to study in today’s hyper-specialized world. And it is an important history as nostalgia for this period is part of what drove some segments of the British population to embrace Brexit. Britain in the 19th century could celebrate military victories and naval superiority. This was the era of great statesmen such as Peel, Disraeli and Gladstone and the era of great political reform and potential revolution. This was the period of great technological and material progress as celebrated by The Great Exhibition of 1851. The sun never set on the British Empire as British Imperialism spread to every continent and Queen Victoria ruled over one in every five people in the world. But most people in Britain were still desperately poor. The Irish were starving. And colonial wars took money and men to manage. Dickens would write “It was the best of times and the worst of times” to describe the French Revolution. But the same could be said of 19th c. Britain. Cannadine begins his history with the 1800 Act of Union which created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. -

Teaching Eighteenth-Century French Literature: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Eighteenth-Century Modernities: Present Contributions and Potential Future Projects from EC/ASECS (The 2014 EC/ASECS Presidential Address) by Christine Clark-Evans It never occurred to me in my research, writing, and musings that there would be two hit, cable television programs centered in space, time, and mythic cultural metanarrative about 18th-century America, focusing on the 1760s through the 1770s, before the U.S. became the U.S. One program, Sleepy Hollow on the FOX channel (not the 1999 Johnny Depp film) represents a pre- Revolutionary supernatural war drama in which the characters have 21st-century social, moral, and family crises. Added for good measure to several threads very similar to Washington Irving’s “Legend of Sleepy Hollow” story are a ferocious headless horseman, representing all that is evil in the form of a grotesque decapitated man-demon, who is determined to destroy the tall, handsome, newly reawakened Rip-Van-Winkle-like Ichabod Crane and the lethal, FBI-trained, diminutive beauty Lt. Abigail Mills. These last two are soldiers for the politically and spiritually righteous in both worlds, who themselves are fatefully inseparable as the only witnesses/defenders against apocalyptic doom. While the main characters in Sleepy Hollow on television act out their protracted, violent conflict against natural and supernatural forces, they also have their own high production-level, R & B-laced, online music video entitled “Ghost.” The throaty feminine voice rocks back and forth to accompany the deft montage of dramatic and frightening scenes of these talented, beautiful men and these talented, beautiful women, who use as their weapons American patriotism, religious faith, science, and wizardry. -

Research Outputs Book Review: 'Unearthly Beauty: the Aesthetic of St John Henry Newman

Research outputs Book Review: 'Unearthly Beauty: The Aesthetic of St John Henry Newman. By Guy Nicholls'. Leominster, Gracewing, 2019. ISBN: 978 085244 947 9 Nockles, P., 3 Feb 2021, In: Journal of Theological Studies. DOI: 10.1093/jts/fla155 'Alexander Knox: Neglected Progenitor of the Oxford Movement'. Nockles, P., 2021, In: Ecclesiology. 17 (2021), p. 271-279 9 p. Book Review of 'Victorious Century: The United Kingdom, 1800-1906, by David Cannadine'. Nockles, P., 1 Aug 2020, In: Newman Studies Journal. 17, 1, p. 161-165 5 p. 'Saint John Henry Newman: Anglican and Catholic' Nockles, P., 22 Jul 2020, (E-pub ahead of print) In: International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church. p. 1-12 13 p. DOI: 10.1080/1474225X.2020.1783811 'The Current State of Newman Scholarship'. Nockles, P., Apr 2020, In: British Catholic History. 35, 1, p. 105 127 p., 23. DOI: 10.1017/bch.2020.6 Winds of Change: Book review: Trystan Owain Hughes, 'Winds of Change: The Roman Catholic Church and Society in Wales, 1916-1962 (Cardiff: Unversity of Wales Press, 2017. £24.99. pp. xii + 300. ISBN: 978-1-78683-077-7). Nockles, P., Jul 2018, In: Expository Times. 129, 10, p. 483-484 2 p. Book Review: 'The Catholic Church and the Campaign for Emancipation in Ireland and England, by Ambrose Macaulay. Nockles, P., Jun 2018, In: The English Historical Review. 133, 563, p. 980-982 3 p. Book review: 'Giles Mercer, Convert, Scholar, Bishop. William Brownlow 1830-1901, Bath: Downside Abbey Press, 2016. pp. 608, £30, ISBN: 978-0-950-275949'. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. Allan Ramsay, ‘Verses by the Celebrated Allan Ramsay to his Son. On his Drawing a Fine Gentleman’s Picture’, in The Scarborough Miscellany for the Year 1732, 2nd edn (London: Wilford, 1734), pp. 20–22 (p. 20, p. 21, p. 21). 2. See Iain Gordon Brown, Poet & Painter, Allan Ramsay, Father and Son, 1684–1784 (Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland, 1984). 3. When considering works produced prior to the formation of the United Kingdom in 1801, I have followed in this study the eighteenth-century prac- tice of using ‘united kingdom’ in lower case as a synonym for Great Britain. 4. See, respectively, Kurt Wittig, The Scottish Tradition in Literature (London: Oliver and Boyd, 1958); G. Gregory Smith, Scottish Literature: Character and Influence (London: Macmillan, 1919); Hugh MacDiarmid, A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, ed. by Kenneth Buthlay (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1988); David Craig, Scottish Literature and the Scottish People, 1680–1830 (London: Chatto & Windus, 1961); David Daiches, The Paradox of Scottish Culture: The Eighteenth-Century Experience (London: Oxford University Press, 1964); Kenneth Simpson, The Protean Scot: The Crisis of Identity in Eighteenth-Century Scottish Literature (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1988); Robert Crawford, Devolving English Literature (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992); Murray Pittock, Poetry and Jacobite Politics in Eighteenth- Century Britain and Ireland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994) and idem, Scottish and Irish Romanticism (Oxford: Oxford University -

Oriel College Record

Oriel College Record 2020 Oriel College Record 2020 A portrait of Saint John Henry Newman by Walter William Ouless Contents COLLEGE RECORD FEATURES The Provost, Fellows, Lecturers 6 Commemoration of Benefactors, Provost’s Notes 13 Sermon preached by the Treasurer 86 Treasurer’s Notes 19 The Canonisation of Chaplain’s Notes 22 John Henry Newman 90 Chapel Services 24 ‘Observing Narrowly’ – Preachers at Evensong 25 The Eighteenth Century World Development Director’s Notes 27 of Revd Gilbert White 92 Junior Common Room 28 How Does a Historian Start Middle Common Room 30 a New Book? She Goes Cycling! 95 New Members 2019-2020 32 Eugene Lee-Hamilton Prize 2020 100 Academic Record 2019-2020 40 Degrees and Examination Results 40 BOOK REVIEWS Awards and Prizes 48 Gonzalo Rodriguez-Pereyra, Leibniz: Graduate Scholars 48 Discourse on Metaphysics 104 Sports and Other Achievements 49 Robert Wainwright, Early Reformation College Library 51 Covenant Theology: English Outreach 53 Reception of Swiss Reformed Oriel Alumni Advisory Committee 55 Thought, 1520-1555 106 CLUBS, SOCIETIES NEWS AND ACTIVITIES Honours and Awards 110 Chapel Music 60 Fellows’ and Lecturers’ News 111 College Sports 63 Orielenses’ News 114 Tortoise Club 78 Obituaries 116 Oriel Women’s Network 80 Other Deaths notified since Oriel Alumni Golf 82 August 2019 135 DONORS TO ORIEL Provost’s Court 138 Raleigh Society 138 1326 Society 141 Tortoise Club Donors 143 Donors to Oriel During the Year 145 Diary 154 Notes 156 College Record 6 Oriel College Record 2020 VISITOR Her Majesty the Queen