00 Prelims LH:Layout 1 12/2/07 12:46 Page I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Miare Festival Is an Expression of the Living Faith of Local Fishermen. Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription

The Miare Festival is an expression of the living faith of local fishermen. Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria Under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value The Sacred Island of Okinoshima and Associated Sites in the Munakata Region Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The Sacred Island of Okinoshima and Associated Sites in the Munakata Region is located in the western coastal area of Japan. It is a serial cultural property that has eight component parts, all of which are linked to the worship of a sacred island that has continued from the fourth century to the present day. These component parts include Okitsu-miya of Munakata Taisha, which encompasses the entire island of Okinoshima and its three attendant reefs, located in the strait between the Japanese archipelago and the Korean peninsula; Okitsu- miya Yohaisho and Nakatsu-miya of Munakata Taisha, located on the island of Oshima; and Hetsu-miya of Munakata Taisha and the Shimbaru-Nuyama Mounded Tomb Group, located on the main island of Kyushu. Okinoshima has unique archaeological sites that have survived nearly intact, providing a chronological account of how ancient rituals based on nature worship developed from the fourth to the ninth centuries. It is of outstanding archaeological value also because of the number and quality of offerings discovered there, underscoring the great importance of the rituals and serving as evidence of their evolution over a period of 500 years, in the midst of a process of dynamic overseas exchange in East Asia. -

Title Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Type Thesis URL

Title Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Type Thesis URL http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/6205/ Date 2013 Citation Spławski, Piotr (2013) Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939). PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Creators Spławski, Piotr Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Piotr Spławski Submitted as a partial requirement for the degree of doctor of philosophy awarded by the University of the Arts London Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) Chelsea College of Art and Design University of the Arts London July 2013 Volume 1 – Thesis 1 Abstract This thesis chronicles the development of Polish Japonisme between 1885 and 1939. It focuses mainly on painting and graphic arts, and selected aspects of photography, design and architecture. Appropriation from Japanese sources triggered the articulation of new visual and conceptual languages which helped forge new art and art educational paradigms that would define the modern age. Starting with Polish fin-de-siècle Japonisme, it examines the role of Western European artistic centres, mainly Paris, in the initial dissemination of Japonisme in Poland, and considers the exceptional case of Julian Żałat, who had first-hand experience of Japan. The second phase of Polish Japonisme (1901-1918) was nourished on local, mostly Cracovian, infrastructure put in place by the ‘godfather’ of Polish Japonisme Żeliks Manggha Jasieski. His pro-Japonisme agency is discussed at length. -

A Critical Analysis of Travel Essays of Foreign Visitors to Meiji Era Enoshima

Journal of the Ochanomizu University English Society No. 4(2013) Encounters with the Goddess: A Critical Analysis of Travel Essays of Foreign Visitors to Meiji Era Enoshima Patrick Hein Synopsis Enoshima is an important pilgrimage site dedicated to the Benten goddess. This essay exposes how two early Meiji foreign travellers –the American zoologist Edward S. Morse and the Irish writer Lafcadio Hearn- have presented and interpreted what they saw in Enoshima. Both men try to convey a frank and accurate picture of their observations but ultimately fail to fully capture and grasp the deeper social and historical context of Enoshima’s significance and its importance for religious leaders and worldly rulers of the time. The reasons for this are twofold: their intellectual representations of Enoshima are influenced and shaped by their translators on one hand and by their strong exposure to the dominant 19th century ideology of social Darwinism on the other hand. 1. Introduction When individuals invent new communities, societies, and nations—both now and in the past—they create gods, rituals, and miracles to support them. Even what seem to be some of the most timeless and sacred sites in the world have been shaped, reshaped, and reinterpreted to find new relevance and meaning in a world of incessant change. A major challenge for anyone interested in Japan today is to understand where ancient religious worship, pilgrimage and the gods fit in the structures of modern contemporary Japan. Many stories, tales, plays and novels have traced the power of sacred places and benevolent gods (Hardacre, Thal). While some stories focus upon the miraculous and divine power of religion and the gods, other narratives seem to underscore the more profane and tangible nature of such beliefs. -

FESTIVALS Worship, Four Elements of Worship, Worship in the Home, Shrine Worship, Festivals

PLATE 1 (see overleaf). OMIVA JINJA,NARA. Front view of the worshipping hall showing the offering box at the foot of the steps. In the upper foreground is the sacred rope suspended between the entrance pillars. Shinto THE KAMI WAY by DR. SOKYO ONO Professor, Kokugakuin University Lecturer, Association of Shinto Shrines in collaboration with WILLIAM P. WOODARD sketches by SADAO SAKAMOTO Priest, Yasukuni Shrine TUTTLE Publishing Tokyo | Rutland, Vermont | Singapore Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd., with editorial offices at 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon, VT 05759 USA and 61 Tai Seng Avenue #02-12, Singapore 534167. © 1962 by Charles E. Tuttle Publishing Company, Limited All rights reserved LCC Card No. 61014033 ISBN 978-1-4629-0083-1 First edition, 1962 Printed in Singapore Distributed by: Japan Tuttle Publishing Yaekari Building, 3rd Floor 5-4-12 Osaki, Shinagawa-ku Tokyo 141-0032 Tel: (81)3 5437 0171; Fax: (81)3 5437 0755 Email: [email protected] North America, Latin America & Europe Tuttle Publishing 364 Innovation Drive North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436 USA Tel: 1 (802) 773 8930; Fax: 1 (802) 773 6993 Email:[email protected] www.tuttlepublishing.com Asia Pacific Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd. 61 Tai Seng, Avenue, #02-12 Singapore 534167 Tel: (65) 6280 1330; Fax: (65) 6280 6290 Email: [email protected] www.periplus.com 15 14 13 12 11 10 38 37 36 35 34 TUTTLE PUBLISHING® is a registered trademark of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. CONTENTS Foreword -

MUSEUM of FINE ARTS, BOSTON Annual Report Deaccessions July 2012–June 2013

MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON Annual Report Deaccessions July 2012–June 2013 Asia & Africa/Japanese Object No. Artist Title Culture/Date/Place Medium Credit Line 1. 11.13602 Utagawa Toyokuni I (Japanese, Courtesans Promenading on the Japanese, Edo period, Woodblock print William Sturgis Bigelow Collection 1769–1825) Nakanochô about 1795 (Kansei 7) (nishiki-e); ink and Publisher: Izumiya Ichibei 吉原仲の町花魁道中 color on paper (Kansendô) (Japanese) 2. 11.14024 Chôbunsai Eishi (Japanese, Toyohina, from the series Japanese, Edo period, Woodblock print William Sturgis Bigelow Collection 1756–1829) Flowerlike Faces of Beauties about 1793 (Kansei 5) (nishiki-e); ink and Publisher: Nishimuraya Yohachi (Bijin kagan shû) color on paper (Eijudô) (Japanese) 「美人花顔集 豊ひな」 3. 11.14046 Chôbunsai Eishi (Japanese, Fuji no uraba, from the series Japanese, Edo period, Woodblock print William Sturgis Bigelow Collection 1756–1829) Genji in Fashionable Modern about 1791–92 (Kansei (nishiki-e); ink and Guise (Fûryû yatsushi Genji) 3–4) color on paper 風流やつし源氏 藤裏葉 4. 11.14245 Kitagawa Utamaro I (Japanese, Camellia, from the series Flowers Japanese, Edo period, Woodblock print William Sturgis Bigelow Collection (?)–1806) of Edo: Girl Ballad Singers (Edo about 1803 (Kyôwa 3) (nishiki-e); ink and Publisher: Yamaguchiya no hana musume jôruri) color on paper Chûemon (Chûsuke) (Japanese) 「江戸の花娘浄瑠璃」 椿 5. 11.14253 Kitagawa Utamaro I (Japanese, Maple Leaves, from the series Japanese, Edo period, Woodblock print William Sturgis Bigelow Collection (?)–1806) Flowers of Edo: Girl Ballad about 1803 (Kyôwa 3) (nishiki-e); ink and Publisher: Yamaguchiya Singers (Edo no hana musume color on paper Chûemon (Chûsuke) (Japanese) jôruri) 「江戸の花娘浄瑠璃」 紅葉 6. 11.14385 Kitagawa Utamaro I (Japanese, Women Imitating an Imperial Japanese, Edo period, Woodblock print William Sturgis Bigelow Collection (?)–1806) Procession 1805 (Bunka 2), 10th (nishiki-e); ink and Publisher: Wakasaya Yoichi 御所車見立て行列 month color on paper (Jakurindô) (Japanese) 7. -

The Goddess and the Dragon

The Goddess and the Dragon The Goddess and the Dragon: A Study on Identity Strength and Psychosocial Resilience in Japan By Patrick Hein The Goddess and the Dragon: A Study on Identity Strength and Psychosocial Resilience in Japan, by Patrick Hein This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Patrick Hein All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6521-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6521-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ............................................................................................. vii List of Figures............................................................................................. ix List of Appendices ...................................................................................... xi Preface ...................................................................................................... xiii Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Encounters with the Goddess: A Critical Analysis of Travel Essays of Foreign Visitors to Meiji Era Enoshima Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement 『神道事典』巻末年表、英語版 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics Kokugakuin University 2016 Preface This book is a translation of the chronology that appended Shinto jiten, which was compiled and edited by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. That volume was first published in 1994, with a revised compact edition published in 1999. The main text of Shinto jiten is translated into English and publicly available in its entirety at the Kokugakuin University website as "The Encyclopedia of Shinto" (EOS). This English edition of the chronology is based on the one that appeared in the revised version of the Jiten. It is already available online, but it is also being published in book form in hopes of facilitating its use. The original Japanese-language chronology was produced by Inoue Nobutaka and Namiki Kazuko. The English translation was prepared by Carl Freire, with assistance from Kobori Keiko. Translation and publication of the chronology was carried out as part of the "Digital Museum Operation and Development for Educational Purposes" project of the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Organization for the Advancement of Research and Development, Kokugakuin University. I hope it helps to advance the pursuit of Shinto research throughout the world. Inoue Nobutaka Project Director January 2016 ***** Translated from the Japanese original Shinto jiten, shukusatsuban. (General Editor: Inoue Nobutaka; Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1999) English Version Copyright (c) 2016 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. All rights reserved. Published by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University, 4-10-28 Higashi, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Japan. -

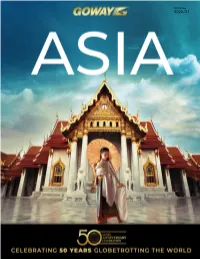

US Edition 2020/21 Goway: the Only Way to Go to Asia

US Edition 2020/21 Goway: The Only Way To Go To Asia ” E XOTIC" is often used when describing Asia. Come on an unforgettable journey with the experts to Asia...an amazingly diverse continent, a land of mystery, legend, and a place where you can experience culture at its most magnificent. There is so much to see and do in Asia, mainly because it is so BIG! Marco Polo travelled for seven- teen years and didn’t see it all. My son completed a twelve month backpacking journey in Asia and only visited eight countries (including the two largest, India and China). If you have already been to Asia, you will know what I am saying. If you haven’t, you should go soon because you will want to keep going back. For our most popular travel ideas to visit Asia, please keep reading our brochure. When you travel with Goway you become part of a special fraternity of travellers of whom we care about Bruce and Claire Hodge in Varanasi very much. Our company philosophy is simple – we want you to be more than satisfied with our services so that (1) you will recommend us to your friends and (2) you will try one of our other great travel ideas. I personally invite you to join the Goway family BRUCE J. HODGE of friends who have enjoyed our services over the last 50 years. Come soon to exotic Asia… with Goway. Founder & President 2 Visit www.goway.com for more details Trans Siberian Railway Ulaan Baatar RUSSIA Karakorum MONGOLIA Tsar’s Gold Urumqi Turpan Beijing Kashgar Sea of Japan Dunhuang Seoul Gyeongju Tokyo Tibet SOUTH KOREA Kyoto Express Hakone CHINA East China -

Annual Report for the Year 2017-2018

SEATTLE ART MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2017 – 2018 JULY 1, 2017 THROUGH JUNE 30, 2018 CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR & CEO, CHAIRMAN & PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD 3 SEATTLE ART MUSEUM 12 ASIAN ART MUSEUM 18 OLYMPIC SCULPTURE PARK 24 EXHIBITIONS, INSTALLATIONS & PUBLICATIONS 27 ACQUISITIONS 40 FINANCIAL & ATTENDANCE REPORT 44 EDUCATION & PUBLIC PROGRAMS 48 BOARD OF TRUSTEES, STAFF & VOLUNTEERS 56 DONOR RECOGNITION Cover: Installation view of Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors at Seattle Art Museum, 2017, photo: Natali Wiseman. Contents: Installation view of Figuring History: Robert Colescott, Kerry James Marshall, Mickalene Thomas at Seattle Art Museum, 2018, photo: Stephanie Fink. ANNUAL REPORT 2017 – 18 Photo: Natali Wiseman. LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR The fiscal year of 2017/2018 was an exciting one publications, programs, acquisitions, and initiatives for all three locations of the Seattle Art Museum. that helped us accomplish our mission of & CEO, CHAIRMAN & It included astounding highlights such as the connecting art to life in this fiscal year. PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD resounding success of the popular Yayoi Kusama: We are proud of the hard work of all involved and Infinity Mirrors exhibition at Seattle Art Museum, wish to extend our deepest thanks to our members, the official groundbreaking that kicked off the donors, sponsors, volunteers, trustees, and staff $56 million restoration and enhancement of whose support, generosity, and tireless work helped the beautiful Art Deco Asian Art Museum, and make these great achievements possible. a tremendous two-day celebration in honor of the founders of the Olympic Sculpture Park, Jon Kimerly Rorschach and Mary Shirley, that raised nearly $700,000 to Illsley Ball Nordstrom Director and CEO benefit programs at the sculpture park. -

Business Movie Reviews

ESTABLISHED 1970 BY CORKY ALEXANDER VOL. 39 NO. 15 AUG 01 – 14 2008 FREE KIDS’ OLYMPICS LEARNING SPORTSMANSHIP THIS SUMMER FIRST TIME FITNESS? TRY THE FLEXBAND BUSINESS IAN DE STAINS TALKS OLYMPICS MOVIE REVIEWS HOW DID SEX AND THE CITY DO WITH OUR REVIEWER? ATHLETIC INSPIRATION FROM OLYMPIC HOOPS TO HULA HOOPS— GETTING ACTIVE IN TOKYO ALSO ONLINE AT WWW.WEEKENDERJAPAN.COM 42$8.41/.2(3(.- VOLVO XC90 5.+5." 12$TL=P=J@@ELHKI=P2 +$2/1(5(+$&$#3.2$15$8.4 Call Steven Wanchap at: (03) 3585-2627 E-Mail: [email protected] expat.volvocars.com MAKE MORE OF YOUR STAY IN JAPAN. FIND OUT HOW YOU CAN PURCHASE A FACTORY-NEW VOLVO ON VERY SPECIAL TERMS. VOLVO V70 VOLVO C70 VOLVO S80 VOLVO C30 LOCAL DELIVERY US/UK DELIVERY EUROPEAN DELIVERY } Full English Service Order 3–4 months before repatriation Learn how you can purchase a brand } + English NAVI + Highway pass (ETC) and enjoy benefits: new Volvo Tax Free! Contact us to see } Generous savings on MSRP if your country is applicable for this } Insurance handling advantageous program. } Convenient dealer location } Custom ordered Volvo in home specifi cation } Attractive low interest fi nancing } All shipping and insurance included http://www.volvocars.co.jp/ } Car waiting for you when you return } Attractive fi nancing http://vcic.volvocars.com/ TEST DRIVE YOUR DREAM VOLVO! 4 | Weekender—Athletic Inspiration Issue FAMILY FOCUS ESTABLISHED 1970 BY CORKY ALEXANDER VOL. 39 NO. 15 AUG 01 – 14 2008 FREE 06 Community Calendar The city events to be seen at 08 Feature Getting active in Tokyo 10 Movie Reviews -

Soul of Meiji: Edward Sylvester Morse, His Day by Day with Kindhearted People

20th Anniversary Special Exhibition of the opening of Edo-Tokyo Museum Soul of Meiji: Edward Sylvester Morse, his day by day with kindhearted people Dates : September 14, 2013 - December 8, 2013 Venue : 1st Floor Special Exhibition Gallery, Edo-Tokyo Museum Organizer : Tokyo Metoropolitan Fondation for History and Culture, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo Tokyo Museum, The Asahi Shimbun List Works Chapter 1. Dr. Morse No. Title Date Artist, Maker Location and Owner 1 Portrait of Edward S. Morse 1914 Frank W. Benson Peabody Essex Museum 2 Shells gathered at Enoshima ca.1877 Edward S. Morse collected Peabody Essex Museum 3 Shell Mounds of Omori July, 1879 Edward S. Morse Edo Tokyo Museum 4 Ark shell Late Jomon The University Museum, The University of Tokyo 5 A clam Late Jomon The University Museum, The University of Tokyo 6 Ark shell Late Jomon The University Museum, The University of Tokyo 7 Scapharca kagoshimensis Late Jomon The University Museum, The University of Tokyo 8 Vase Late Jomon The University Museum, The University of Tokyo 9 Vase Late Jomon The University Museum, The University of Tokyo 10 Hanger earthenware vessel Late Jomon The University Museum, The University of Tokyo 11 Annular earthenware vessel Late Jomon The University Museum, The University of Tokyo 12 Vase Late Jomon The University Museum, The University of Tokyo Chapter 2. Japan and Japanese No. Title Date Artist, Maker Location and Owner 13 Japan day by day : 1877, 1878-79, 1882-83 1917 Edward S. Morse Edo Tokyo Museum 14 Japanese homes and their surroundings, with 1886 Edward S. Morse Edo Tokyo Museum illustrations by the author 15 Map of Japan Published 1876, and Used Publisher, Yamanaka Ichibei. -

Lafcadio Hearn Glimpses of an Unfamiliar Japan

LAFCADIO HEARN GLIMPSES OF AN UNFAMILIAR JAPAN 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted GLIMPSES OF UNFAMILIAR JAPAN First Series by LAFCADIO HEARN (dedication) TO THE FRIENDS WHOSE KINDNESS ALONE RENDERED POSSIBLE MY SOJOURN IN THE ORIENT, PAYMASTER MITCHELL McDONALD, U.S.N. AND BASIL HALL CHAMBERLAIN, ESQ. Emeritus Professor of Philology and Japanese in the Imperial University of Tokyo I DEDICATE THESE VOLUMES IN TOKEN OF AFFECTION AND GRATITUDE CONTENTS PREFACE 1 MY FIRST DAY IN THE ORIENT 2 THE WRITING OF KOBODAISHI 3 JIZO 4 A PILGRIMAGE TO ENOSHIMA 5 AT THE MARKET OF THE DEAD 6 BON-ODORI 7 THE CHIEF CITY OF THE PROVINCE OF THE GODS 8 KITZUKI: THE MOST ANCIENT SHRINE IN JAPAN 9 IN THE CAVE OF THE CHILDREN'S GHOSTS 10 AT MIONOSEKI 11 NOTES ON KITZUKI 12 AT HINOMISAKI 13 SHINJU 14 YAEGAKI-JINJA 15 KITSUNE PREFACE In the Introduction to his charming Tales of Old Japan, Mr. Mitford wrote in 1871: 'The books which have been written of late years about Japan have either been compiled from official records, or have contained the sketchy impressions of passing travellers. Of the inner life of the Japanese the world at large knows but little: their religion, their superstitions, their ways of thought, the hidden springs by which they move--all these are as yet mysteries.' This invisible life referred to by Mr. Mitford is the Unfamiliar Japan of which I have been able to obtain a few glimpses. The reader may, perhaps, be disappointed by their rarity; for a residence of little more than four years among the people--even by one who tries to adopt their habits and customs--scarcely suffices to enable the foreigner to begin to feel at home in this world of strangeness.