Losing Your Internet: Narratives of Decline Among Long- Time Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matrix Become a Fan Without Being Irrevocably Cut Off from Any SF Roots

£1.25 110 NewsCetter Of tile Brittsll Science Yiction Association Ye6ruar9 - Marcil 1994 Morrix110 Datarife Determinants It seems to make more Sense to start a new year in February when the Membership weather is once more becoming civilised, rather than having it This costs £15 per year (UK and EC). immediately adjacent to the glullony and indulgence of Christmas. A British winter seems to be an endless tunnel of low-level misery and New members: Alison Cook, 27 Albemarle Drive. Grove, Wantage. dampness, so the first appearance of Ihe sun produces a primitive Oxon aXIl ON8 resurgence of joy. As the skeleton trees slowly blur into buds and the ground changes from mud to mud with stalks, there seems more point Renewals: Keith Freeman, 269 Wykeham Road, Reading RG6 IPL to life: and, perhaps, there may seem to be more to life than reading SF. USA: Cy Chauvin. 14248 Wilfred Street, Detroit. M148213, USA Unlike the metamorphosis from larva to dragon fly, an SF reader can Matrix become a fan without being irrevocably cut off from any SF roots. A fan will almost by definition stan as an SF reader who wishes to take Jenny and Steve Glover. 16 Aviary Place, Leeds LSl2 2NP a mOTe active role in the SF community. I'm not entirely convinced. Tel: 0532 791264 though, that people deliberately set out to become fans, There are a whole series of circumstances which seem to be coincidences and Vector which cascade onto the unwary reader but which will fail to activate anyone unless some spark of curiosity or sense of wonder gets ignited Catie Cary. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items FAMOUS AMERICAN ILLUSTRATORS On our Cover Specially Priced SOI file copies from 1997! Our NAUGHTY AND NICE The Good Girl Art of Highest Recommendation. By Bruce Timm Publisher Edition Arpi Ermoyan. Fascinating insights New Edition. Special into the lives and works of 82 top exclusive Publisher’s artists elected to the Society of Hardcover edition, 1500. Illustrators Hall of Fame make Highly Recommended. this an inspiring reference and art An extensive survey of book. From illustrators such as N.C. Bruce Timm’s celebrated Wyeth to Charles Dana Gibson to “after hours” private works. Dean Cornwell, Al Parker, Austin These tastefully drawn Briggs, Jon Whitcomb, Parrish, nudes, completed purely for Pyle, Dunn, Peak, Whitmore, Ley- fun, are showcased in this endecker, Abbey, Flagg, Gruger, exquisite new release. This Raleigh, Booth, LaGatta, Frost, volume boasts over 250 Kent, Sundblom, Erté, Held, full-color or line and pencil Jessie Willcox Smith, Georgi, images, each one full page. McGinnis, Harry Anderson, Bar- It’s all about sexy, nubile clay, Coll, Schoonover, McCay... girls: partially clothed or fully nude, of almost every con- the list of greats goes on and on. ceivable description and temperament. Girls-next-door, Society of Illustrators, 1997. seductresses, vampires, girls with guns, teases...Timm FAMAMH. HC, 12x12, 224pg, FC blends his animation style with his passion for traditional $40.00 $29.95 good-girl art for an approach that is unmistakably all his JOHN HASSALL own. Flesk, 2021. Mature readers. NOTE: Unlike the The Life and Art of the Poster King first, Timm didn’t sign this second printing. -

Interview with Ambassador Keith L. Wauchope

Library of Congress Interview with Ambassador Keith L. Wauchope Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR KEITH L. WAUCHOPE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: March 8, 2002 Copyright 2007 ADST Q: Today is March 8th, 2002. This is an interview with Keith Wauchope. This is done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and I'm Charles Stuart Kennedy. Keith, let's start kind of at the beginning. Could you tell me when and where you were born? WAUCHOPE: I was born at Manhattan Hospital in New York City on October 13, 1941. My parents actually lived out on the south shore of Long Island at the time Q: Okay, tell me a bit about, first of all on your father's side, sort of where the family came from and your father's education and what he was doing. WAUCHOPE: Okay, well, my father's father came to the United States in the early 1880s. He was a young man in County Cavan, Ireland and was sent by his father down to Trinity College Dublin to study for the ministry, the Presbyterian ministry. He and his older brother Jack, who was also studying at Trinity, decided they didn't want to become ministers, so they quite literally ran away to sea. He and his brother first went off to Australia and this trade between the UK, between England and Australia. After several voyages in the 1870s my grandfather jumped ship and joined the Australian army. I was told and that he stayed in Australia for only about six months or so, and then deserted the army and signed onto Interview with Ambassador Keith L. -

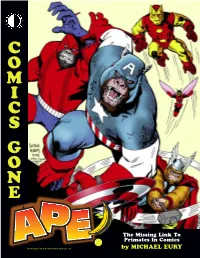

C O M I C S G O N E

C O M I C S G O N E The Missing Link To Primates In Comics by MICHAEL EURY The Avengers TM & © 2007 Marvel Characters, Inc. BARREL OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 5 C H A P T E R 1 BORN TO BE WILD . 6 Girl-Grabbing Gorillas Cover Gallery . .15 Tarzan Through the Years Cover Gallery . 16 Q & Ape with Joe Kubert . 18 Q & Ape with Anne Timmons . 22 C H A P T E R 2 WALKING TALL . 24 Kong-a Line Cover Gallery . 36 Q & Ape with Arthur Adams . 38 Q & Ape with Frank Cho . 44 C H A P T E R 3 MONKEY BUSINESS . 48 Mo’ Monkeys Cover Gallery . 62 Q & Ape with Carmine Infantino . 64 Q & Ape with Tony Millionaire . 68 C H A P T E R 4 GORILLAS IN OUR MIDST . 72 Super-Heroes Battle Super-Gorillas Cover Gallery . 92 Q & Ape with Bob Oksner . 94 Q & Ape with Tim Eldred . 98 C H A P T E R 5 MAKE A MONKEY OUT OF ME . 102 Going Ape Cover Gallery . 118 Q & Ape with Nick Cardy . 120 Q & Ape with Jeff Parker . 124 C H A P T E R 6 WHERE MAN ONCE STOOD SUPREME . 126 Planet of the Apes Cover Gallery . 134 Q & Ape with Doug Moench . 136 Safari-goers and beastmasters never know when they’ll meet a monkey with a mad-on! Watch your step as you bungle into the jungle, where the apes are... BORN TO BE WILD! ave you ever seen a jungle movie that didn’t depict the snorted commands of their middle-aged editors hot to ape H gorilla as really, really angry? That’s fang-snarling, Hollywood’s lucrative jungle craze, tapped the gorilla on the chest-pounding angry. -

Graphic Novel Finding Aid for Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation & Fantasy Last Updated: September 15, 2020

Graphic Novel Finding Aid for Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation & Fantasy Last updated: September 15, 2020 Most books in this list are in English. We have some graphic novels in other languages . Books are listed alphabetically by series title. Books in series are listed in numerical order (if possible) — otherwise they’re listed alphabetically by sub-title. A | B |C |D | E |F |G | H | I| J| K | L | M | N |O | P | Q| R |S | T| U | V | W | X | Y | Z Title Writer/Artist Notes A A.B.C. Warriors. The Mills, Pat and Kevin A.B.C. Warriors began in Mek-nificent Seven O’Neill and Mike Starlord. McMahon A. D.: after death Snyder, Scott and Jeff Lemire A.D.D. : Adolescent Rushkoff, Douglas Demo Division et al. Aama. 1, The smell Peeters, Frederick of warm dust Aama. 2, The Peeters, Frederick invisible throng Aama. 3, The desert Peeters, Frederick of mirrors The Abaddon Shadmi, Koren Abbott Ahmed, Saladin and Originally published in single others magazine form as Abbott, #1-5. Aama. 4, You will be Peeters, Frederick glorious, my daughter Abe Sapien. Vol. 1, Mignola, Mike et al. The drowning Abe Sapien. Vol. 2, Mignola, Mike et al. The devil does not jest and other stories Across the Universe. Moore, Alan et al. “Superman annual” #11; The DC Universe “Detective comics” #549, 550, stories of Alan “Green Lantern” #188; Moore “Vigilante” #17, 18; “The Omega men” #26, 27; “DC Comics presents” #85; “Tales of the Green Lantern corps annual” #2, 3; “Secret origins” #10; “Batman annual” #11 The Action heroes Gill, Joe et al. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR KEITH L. WAUCHOPE Intervie

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR KEITH L. WAUCHOPE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: March 8, 2002 Copyright 2007 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in New York state Johns Hopkins University US Army, Vietnam Combat experiences Viet Cong brutality Jane Fonda Marriage ,ntered the Foreign Service in 19.. Department of State/ FS0/ French language training 19.. Hong 1ong/ 2otation Officer 19..319.8 Visa applicants Macau British Communist campaign China turmoil ,nvironment 0nsurrection activities Ft. 6amy, Chad/ Political7,conomic Officer 19.831981 US A0D Development programs Peace Corps The French 2elations with neighbors 0sraelis President Francois Tombalbaye 6ibya 0nfrastructure Drought 1 ,nvironment State Department/ Cultural Affairs Officer, Africa Programs 198131983 Student exchange programs Soviet programs Fulbright program Other US programs Foreign based University support State Department/ Haiti and Bahamas Desk Officer7Bahamas, 198331984 Netherland Antilles & French West 0ndies Desk Officer Bahamas independence Baby Doc Haiti government Haitian illegals US Haitian organizations Bi3lateral issues Vesco affair Bahamas A0D project ,nvironment Drugs 6eave Without Pay 1985 Asmara, ,ritrea/ Deputy Principal Officer 198531988 0talians Uprising ,nvironment The Derg ,thiopia ,ritrean Peoples 6iberation Front (,P6FA 1agnew Station 2elations with ,mbassy Addis Ababa Security 0nsurgency Mengistu Haile Selassie 2eligious groups Martial -

Fantagraphics Mindviscosity Matt Furie Pub Date

FANTAGRAPHICS Fantagraphics Mindviscosity Summary: Furie's cheerful, anthropomorphic comics Matt Furie character, Pepe the Frog, became a meme that was Pub Date: 9/1/20 appropriated by hate groups (as seen in the documentary $39.99 USD Feels Good Man, which premiered at the Sundance Film 196 pages Festival.) Furie’s recent paintings reflect this experience. This is a showcase for an unsettling menagerie; creatures seem to be hiding their true intentions. Furie is plumbing darker depths in these works, despite the paintings' inviting colors and friendly cartoon iconography. Kodansha Comics Saint Young Men 3 Summary: The divine live among us…in a flat in Hikaru Nakamura western Tokyo! After centuries of hard work, Jesus and Pub Date: 9/1/20 Buddha take a break from their heavenly duties to relax $23.99 USD among the people of Japan, and their adventures in this 288 pages lighthearted buddy comedy are sure to bring mirth and merriment to all! Buddha the Enlightened One and Jesus, Son of God have successfully brought the 20th century to a close, and after a few millennia of guiding humanity to salvation, these two sacred ones are in need of some rest and relaxation. They decide to share an apartment on Earth in Tokyo, but living among mortals in the 21st century is no cakewalk for the Street Noise Books Spellbound : A Graphic Memoir Summary: The meticulous artwork of transgender Bishakh Som artist Bishakh Som gives us the rare opportunity to see Pub Date: 9/1/20 the world through another lens. $18.99 USD This exquisite graphic novel memoir by a transgender artist, 160 pages explores the concept of identity by inviting the reader to view the author moving through life as she would have us see her, that is, as she sees herself. -

DRAGON Magazine Is Available at Hobby Were Apparently True at the Time He Wrote Stores and Bookstores Throughout the United Halt! Who Goes There?

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief: Kim Mohan Editorial staff: Roger Raupp Time trouble Patrick Lucien Price Mary Kirchoff One of the things we dont do very well Vol. IX, No. 4 September 1984 Roger Moore (and therefore dont do very often) is keep Subscriptions: Mellody Knull up with happenings in the real world. Its SPECIAL ATTRACTION Contributing Editors: Ed Greenwood tough to be timely when you try to cover Katherine Kerr something in a monthly magazine first of Ken Rolston all because it only comes out once a month, CREATURE CATALOG. .following Advertising Sales Administrator: Twenty-nine new monsters page 46 Mary Parkinson and second of all because we finish produc- tion of an issue one month before it gets This issues contributing artists: Denis Beauvais Keith Parkinson printed and mailed. In even the best of Roger Raupp Larry Elmore cases, that usually translates into at least a OTHER FEATURES Bob Maurus Bob Lilly six-week time lag between when something David Sutherland Kurt Erichsen happens and our first chance to tell you Survival is a group effort . .8 Marsha Kauth E. G. Walters about it. How populations replenish themselves Dave LaForce Craig Smith In the worst of cases, the time lag is Jim Holloway Dave Trampier considerably longer than that. As an exam- Six very special shields . .14 DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is ple of how bad things can get, heres the Protection and much, much more published monthly for a subscription price of $24 per year by Dragon Publishing, a division of story of Comstar Enterprises and that com- The many types of magic. -

Audiovisual Representations of Artificial Intelligence in Dystopian Tech Societies: Scaremongering Or Reality? the Cases of Black Mirror (Charlie

Audiovisual representations of Artificial Intelligence in Dystopian Tech Societies: Scaremongering or Reality? The Cases of Black Mirror (Charlie 90) Brooker, 2011), Ex Machina (Alex Garland, 2017) and Her (Spike Jonze, 2014) - 02 - Goksu Akkan http://hdl.handle.net/10803/671832 Generalitat 472 (28 de Catalunya núm. Rgtre. Fund. ió ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials undac F d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. Universitat Ramon Llull Universitat Ramon ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. -

Travel Writing

THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO TRAVEL WRITING EDITED BY PETER HULME University of Essex AND TIM YOUNGS The Nottingham Trent University published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruizde Alarc on´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data The Cambridge companion to travel writing / edited by Peter Hulme and Tim Youngs. p. cm. – (Cambridge companions to literature) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 78140 x–isbn 0 521 78652 5 (pb.) 1. Travelers’ writings, English – History and criticism. 2. Travelers’ writings, American – History and criticism. 3. English prose literature – History and criticism. 4. British – Foreign countries – Historiography. 5. Voyages and travels – Historiography. 6. Travel in literature. 7. Travelers – History. I. Title: Companion to travel writing. II. Hulme, Peter. III. Youngs, Tim. pr756.t72 c36 2002 820.9491 –dc21 2002023425 isbn 0 521 78140 x hardback isbn 0 521 78652 5 paperback CONTENTS List of illustrations page vii Notes on contributors viii Introduction 1 peter hulme and tim youngs part i: surveys 1 Stirrings and searchings (1500–1720) 17 william h. -

Metaphors of Internet

Metaphors of Internet 317450_Markham.indd 1 26-Aug-20 12:07:09 AM Steve Jones General Editor Vol. 122 Te Digital Formations series is part of the Peter Lang Media and Communication list. Every volume is peer reviewed and meets the highest quality standards for content and production. PETER LANG New York • Bern • Berlin Brussels • Vienna • Oxford • Warsaw 317450_Markham.indd 2 26-Aug-20 12:07:09 AM Metaphors of Internet Ways of Being in the Age of Ubiquity Edited by Annette N. Markham and Katrin Tiidenberg PETER LANG New York • Bern • Berlin Brussels • Vienna • Oxford • Warsaw 317450_Markham.indd 3 26-Aug-20 12:07:09 AM Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Markham, Annette N., editor. | Tiidenberg, Katrin, editor. Title: Metaphors of internet: ways of being in the age of ubiquity / edited by Annette N. Markham and Katrin Tiidenberg. Description: New York: Peter Lang, 2020. Series: Digital formations, vol. 122 | ISSN 1526-3169 Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifers: LCCN 2019059859 | ISBN 978-1-4331-7449-0 (hardback: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4331-7450-6 (paperback: alk. paper) | ISBN 978-1-4331-7451-3 (ebook pdf ) ISBN 978-1-4331-7452-0 (epub) | ISBN 978-1-4331-7453-7 (mobi) Subjects: LCSH: Internet—Social aspects. | Internet—Terminology. Classifcation: LCC HM851 .M466 2020 (print) | LCC HM851 (ebook) | DDC 302.23/1—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019059859 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019059860 DOI 10.3726/b16196 Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the “Deutsche Nationalbibliografe”; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de/. -

Hollywood and Africa Recycling the ‘Dark Continent’ Myth, 1908–2020 by Okaka Opio Dokotum

Hollywood and Africa Recycling the ‘Dark Continent’ myth, 1908–2020 by Okaka Opio Dokotum TERMS of USE The African Humanities Program has made this electronic version of the book available on the NISC website for free download to use in research or private study. It may not be re- posted on book or other digital repositories that allow systematic sharing or download. For any commercial or other uses please contact the publishers, NISC (Pty) Ltd. Print copies of this book and other titles in the African Humanities Series are available through the African Books Collective. © African Humanities Program Dedication This book is dedicated to Prof. Emeritus Dr Robert T. Self — teacher, mentor, writing coach and friend, for grounding me in cineliteracy and the grammar of the moving image, and to my dear wife Pamela Renee for her gentle encouragement without which this book would probably have become one of many abandoned projects! About the Series The African Humanities Series is a partnership between the African Humanities Program (AHP) of the American Council of Learned Societies and academic publishers NISC (Pty) Ltd. The Series covers topics in African histories, languages, literatures, philosophies, politics and cultures. Submissions are solicited from Fellows of the AHP, which is administered by the American Council of Learned Societies and financially supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The purpose of the AHP is to encourage and enable the production of new knowledge by Africans in the five countries designated by the Carnegie Corporation: Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda. AHP fellowships support one year’s work free from teaching and other responsibilities to allow the Fellow to complete the project proposed.