Metaphors of Internet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RFID) That Can Be "Read" When Close to a Sensor

PRESS RELEASE, Immediate distribution__ We are working on a new release of materials that includes the audio files of the press conference. Thanks to all the people interested in following up the case, we will keep you informed. We are translating the report to different languages, we have translated already to english, spanish and swedish. Mail us if you can translate the information presented in this website. Thanks! THE PHYSICAL ACCESS SECURITY TO WSIS: A PRIVACY THREAT FOR THE PARTICIPANTS. [IN PICTURES] PRESS RELEASE, Immediate distribution URL: http://www.contra.info/wsis | [email protected] PRESS CONFERENCE Friday 12th December 2003 at 11.30 am à « La Pastorale », Route de Ferney 106 à Genève http://www.pressclub.ch/archives/events_2003/event_121203_1130.htm [Press Release English PDF] - [Nota Prensa en Castellano] - Ass. Prof. Dr. Alberto Escudero-Pascual, Researcher in Computer Security and Privacy, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden (EN, SP) Tel: + 41786677843 , +46 702867989 - Stephane Koch, President Internet Society Geneva, Executive Master of Economic Crime Investigations, Geneva, Switzerland. (FR, EN) Tel: +41 79 607 57 33 - George Danezis, Researcher in Privacy Enhancing Technologies and Computer Security, Cambridge University, UK. (FR, EN, GR) GENEVA, 10th DEC 2003 An international group of independent researchers attending the Word Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) has revealed important technical and legal flaws, relating to data protection and privacy, in the security system used to control access to the UN Summit. The system not only fails to guarantee the promised high levels of security but also introduces the very real possibility of constant surveillance of the representatives of the civil society. -

Losing Your Internet: Narratives of Decline Among Long- Time Users

CHAPTER THREE Losing Your Internet: Narratives of Decline among Long- Time Users KEVIN DRISCOLL Annette Markham’s Life Online (1998) documents an historical conjuncture in which the visibility of the Internet in popular culture outpaced hands-on access for most Americans. At the time that Markham was completing her fieldwork, approximately one-third of Americans reported using the Internet, most of whom were white, wealthy, highly educated, and male (Rainie, 2017). Yet, for half a decade, news and entertainment media had been saturated with stories of the Internet as a technical marvel, economic opportunity, social revolution, and moral threat (Schulte, 2013; Streeter, 2017). Every few months, the cover of Time magazine added a new dimension to the Internet story, from the “info highway” in 1993, to the “cyberporn” panic in 1995, dot-com “golden geeks” in 1996, and the “death of privacy” in 1997. Beyond these sensational headlines, friends and coworkers gos- siped about relationships and romances forming online. Early users of the Internet were similarly enthusiastic and many shared a sense that computer-mediated com- munication might transform the social world. Even Markham described her initial observations of the internet and its growing user population as “astounding” and “extraordinary” (1998, pp. 16–17). At the turn of the century, the Internet seemed charged with unknown possibility. Twenty years later, the structure of feeling that characterized early encoun- ters with the Internet has changed. For millions of people, computer-mediated communication is now an unremarkable aspect of everyday life. In comparison to the fantastical multi-user environments that Markham described in 1998, typical uses of the internet in 2017 seem quite dull: reading the news, solving a crossword 26 | KEVIN DRISCOLL puzzle, shopping for household goods, or arranging meetings with coworkers. -

Violent Victimization in Cyberspace: an Analysis of Place, Conduct, Perception, and Law

Violent Victimization in Cyberspace: An Analysis of Place, Conduct, Perception, and Law by Hilary Kim Morden B.A. (Hons), University of the Fraser Valley, 2010 Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts IN THE SCHOOL OF CRIMINOLOGY FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES © Hilary Kim Morden 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Hilary Kim Morden Degree: Master of Arts (School of Criminology) Title of Thesis: Violent Victimization in Cyberspace: An Analysis of Place, Conduct, Perception, and Law Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. William Glackman, Associate Director Graduate Programs Dr. Brian Burtch Senior Supervisor Professor, School of Criminology Dr. Sara Smyth Supervisor Assistant Professor, School of Criminology Dr. Gregory Urbas External Examiner Senior Lecturer, Department of Law Australian National University Date Defended/Approved: July 13, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract The anonymity, affordability, and accessibility of the Internet can shelter individuals who perpetrate violent acts online. In Canada, some of these acts are prosecuted under existing criminal law statutes (e.g., cyber-stalking, under harassment, s. 264, and cyber- bullying, under intimidation, s. 423[1]). However, it is unclear whether victims of other online behaviours such as cyber-rape and organized griefing have any established legal recourse. -

Metaphors of Big Data

International Journal of Communication 8 (2014), 1690–1709 1932–8036/20140005 Metaphors of Big Data CORNELIUS PUSCHMANN Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany JEAN BURGESS Queensland University of Technology, Australia Metaphors are a common instrument of human cognition, activated when seeking to make sense of novel and abstract phenomena. In this article we assess some of the values and assumptions encoded in the framing of the term big data, drawing on the framework of conceptual metaphor. We first discuss the terms data and big data and the meanings historically attached to them by different usage communities and then proceed with a discourse analysis of Internet news items about big data. We conclude by characterizing two recurrent framings of the concept: as a natural force to be controlled and as a resource to be consumed. Keywords: data, big data, conceptual metaphor, semantics, science, technology, discourse analysis Introduction The media discourse around big data is rife with both strong claims about its potential and metaphors to illustrate these claims. The opening article of a 2011 special issue of the magazine Popular Science reads: “A new age is upon us: the age of data” (”Data Is Power,” 2011). On the magazine’s cover, the headline “Data Is Power” appears next to a Promethean hand bathed in light. In this and similar accounts, big data is suggested to signal the arrival of a new epistemological framework, a Kuhnian paradigm shift with the potential to displace established models of knowledge creation and do away with scientific tenets such as representative sampling and the notion of theory (Anderson, 2008; Mayer- Schönberger & Cukier, 2013; Weinberger, 2012). -

Metaphors of the World Wide Web

. Metaphors of the World Wide Web .......... ‘The Web … is limited only by mans’ imagination’ User 3: 249 Amy Hogan [email protected] www.amyhogan.com . Metaphors of the World Wide Web AMY LOUISE HOGAN A dissertation submitted for the degree of Bachelor of Science University of Bath Department of Psychology June 2002 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this dissertation rests with its author. This copy of the dissertation has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the dissertation and no information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Preface . Metaphors of the World Wide Web ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor. It is the one thing that cannot be learned from others; it is also a sign of genius, since a good metaphor implies an eye for resemblance. -Aristotle, De Poetica, 322 B.C. Many thanks are extended to my dissertation supervisor, Professor Helen Haste – a true master of metaphor. Thanks are also extended to Dr. Anne Beaulieu for her insightful comments when the research was in its early stages. Finally, thanks go to all the participants who found time to detangle themselves from the Web. Preface . Metaphors of the World Wide Web Abstract In just nine years since its debut, the ‘Web’ has generated a wide variety of metaphorical expressions. Metaphor, a powerful linguistic device, is used when users try to make sense of the Web’s foreign environment by describing the unfamiliar in terms of the familiar. -

Matrix Become a Fan Without Being Irrevocably Cut Off from Any SF Roots

£1.25 110 NewsCetter Of tile Brittsll Science Yiction Association Ye6ruar9 - Marcil 1994 Morrix110 Datarife Determinants It seems to make more Sense to start a new year in February when the Membership weather is once more becoming civilised, rather than having it This costs £15 per year (UK and EC). immediately adjacent to the glullony and indulgence of Christmas. A British winter seems to be an endless tunnel of low-level misery and New members: Alison Cook, 27 Albemarle Drive. Grove, Wantage. dampness, so the first appearance of Ihe sun produces a primitive Oxon aXIl ON8 resurgence of joy. As the skeleton trees slowly blur into buds and the ground changes from mud to mud with stalks, there seems more point Renewals: Keith Freeman, 269 Wykeham Road, Reading RG6 IPL to life: and, perhaps, there may seem to be more to life than reading SF. USA: Cy Chauvin. 14248 Wilfred Street, Detroit. M148213, USA Unlike the metamorphosis from larva to dragon fly, an SF reader can Matrix become a fan without being irrevocably cut off from any SF roots. A fan will almost by definition stan as an SF reader who wishes to take Jenny and Steve Glover. 16 Aviary Place, Leeds LSl2 2NP a mOTe active role in the SF community. I'm not entirely convinced. Tel: 0532 791264 though, that people deliberately set out to become fans, There are a whole series of circumstances which seem to be coincidences and Vector which cascade onto the unwary reader but which will fail to activate anyone unless some spark of curiosity or sense of wonder gets ignited Catie Cary. -

Marianne Van Den Boomen Trans Coding the Digital How Metaphors Matter in New Media

MARIANNE VAN DEN BOOMEN TRANS CODING THE DIGITAL HOW METAPHORS MATTER IN NEW MEDIA A SERIES OF READERS PUBLISHED BY THE INSTITUTE OF NETWORK CULTURES ISSUE NO.: 14 MARIANNE VAN DEN BOOMEN TRANSCODING THE DIGITAL HOW METAPHORS MATTER IN NEW MEDIA Theory on Demand #14 Transcoding the Digital: How Metaphors Matter in New Media Author: Marianne van den Boomen Editorial support: Miriam Rasch Design and DTP: Katja van Stiphout Publisher: Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam 2014 Printer: ‘Print on Demand’ First 200 copies printed at Drukkerij Steenman, Enkhuizen ISBN: 978-90-818575-7-4 Earlier and different versions of Chapter 2 has been published in 2008 as ‘Interfacing by Iconic Metaphors’, in Configurations 16 (1): 33-55, and in 2009 as ‘Interfacing by Material Metaphors: How Your Mailbox May Fool You’, in Digital Material: Tracing New Media in Everyday Life and Technology, edited by Marianne van den Boomen, Sybille Lammes, Ann-Sophie Lehmann, Joost Raessens, and Mirko Tobias Schäfer. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, p. 253-266. An earlier and different version of Chapter 6 has been published in 2006 as ‘Transcoding Metaphors after the Mediatic Turn’, in SPIEL 25 (h.1): 47-58. Contact Institute of Network Cultures Phone: +31 20 5951865 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.networkcultures.org This publication is available through various print on demand services. For more information, and a freely downloadable PDF: http://networkcultures.org/publications This publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). TRANSCODING THE DIGITAL 3 TRANSCODING THE DIGITAL HOW METAPHORS MATTER IN NEW MEDIA De transcodering van het digitale Hoe metaforen ertoe doen in nieuwe media (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. -

Judicial Use of Metaphors for New Technologies

“A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME”: JUDICIAL USE OF METAPHORS FOR NEW TECHNOLOGIES Stephanie A. Gore* It is now fairly established in cognitive science and linguistics that metaphors are an essential tool used to organize thought. It is human nature to reach for metaphors when trying to comprehend new concepts. Metaphors, however, may also selectively guide, or misguide, our cognitive processes. By emphasizing one aspect of a concept, a metaphor may blind us to other aspects that are inconsistent with the metaphor. The power of metaphor raises particular concerns in legal disputes wherein the resolution depends on comprehending new or developing technology. First, concerns have been raised regarding the judiciary’s ability to understand complex technology. Second, fear is a powerful barrier to learning, and fear of technology is a common phenomenon. Third, metaphors can be seductive, and may lead a person to end efforts to understand a new (perhaps daunting) concept too quickly. Finally, metaphors play a particularly powerful role in the law, since a court may inherit as precedent metaphors chosen by another court. All of this leads to the potential for the creation of precedents in which courts substitute poorly fitting metaphors for true comprehension of the technology at issue. This Article examines the use of metaphors by courts to comprehend new and developing technologies. It further examines the danger in the selection of definitional metaphors for new and changing technology, and how courts can avoid such dangers through recognition of both the limits of metaphors and the need to keep the metaphorical door open to information—and even * Assistant Professor of Law, Florida State University College of Law; J.D., University of Chicago Law School, 1994; M.S., Computer and Information Sciences, Georgia Institute of Technology, 1989; B.S., Computer Science, Stanford University, 1988. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items FAMOUS AMERICAN ILLUSTRATORS On our Cover Specially Priced SOI file copies from 1997! Our NAUGHTY AND NICE The Good Girl Art of Highest Recommendation. By Bruce Timm Publisher Edition Arpi Ermoyan. Fascinating insights New Edition. Special into the lives and works of 82 top exclusive Publisher’s artists elected to the Society of Hardcover edition, 1500. Illustrators Hall of Fame make Highly Recommended. this an inspiring reference and art An extensive survey of book. From illustrators such as N.C. Bruce Timm’s celebrated Wyeth to Charles Dana Gibson to “after hours” private works. Dean Cornwell, Al Parker, Austin These tastefully drawn Briggs, Jon Whitcomb, Parrish, nudes, completed purely for Pyle, Dunn, Peak, Whitmore, Ley- fun, are showcased in this endecker, Abbey, Flagg, Gruger, exquisite new release. This Raleigh, Booth, LaGatta, Frost, volume boasts over 250 Kent, Sundblom, Erté, Held, full-color or line and pencil Jessie Willcox Smith, Georgi, images, each one full page. McGinnis, Harry Anderson, Bar- It’s all about sexy, nubile clay, Coll, Schoonover, McCay... girls: partially clothed or fully nude, of almost every con- the list of greats goes on and on. ceivable description and temperament. Girls-next-door, Society of Illustrators, 1997. seductresses, vampires, girls with guns, teases...Timm FAMAMH. HC, 12x12, 224pg, FC blends his animation style with his passion for traditional $40.00 $29.95 good-girl art for an approach that is unmistakably all his JOHN HASSALL own. Flesk, 2021. Mature readers. NOTE: Unlike the The Life and Art of the Poster King first, Timm didn’t sign this second printing. -

Metaphoric Interaction with the Internet

USERS’ METAPHORIC INTERACTION WITH THE INTERNET AMY LOUISE HOGAN A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath Department of Psychology March 2008 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with its author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. This thesis may be made available for consultation within the University Library and may be photocopied or lent to other libraries for the purposes of consultation. .................................................................................. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS _____________________________________________ ii LIST OF TABLES __________________________________________________ xi LIST OF FIGURES ________________________________________________ xvi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS __________________________________________ xix ABSTRACT ______________________________________________________ xxi STRUCTURE OF THESIS _________________________________________ xxii DEFINITIONS ___________________________________________________ xxvi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE RESEARCH _________________1 1.1 OVERVIEW _____________________________________________________ 2 1.2 THE INTERNET _________________________________________________ 7 1.2.1 The contemporary Internet: 2001-2004 ____________________________ -

Interview with Ambassador Keith L. Wauchope

Library of Congress Interview with Ambassador Keith L. Wauchope Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR KEITH L. WAUCHOPE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: March 8, 2002 Copyright 2007 ADST Q: Today is March 8th, 2002. This is an interview with Keith Wauchope. This is done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and I'm Charles Stuart Kennedy. Keith, let's start kind of at the beginning. Could you tell me when and where you were born? WAUCHOPE: I was born at Manhattan Hospital in New York City on October 13, 1941. My parents actually lived out on the south shore of Long Island at the time Q: Okay, tell me a bit about, first of all on your father's side, sort of where the family came from and your father's education and what he was doing. WAUCHOPE: Okay, well, my father's father came to the United States in the early 1880s. He was a young man in County Cavan, Ireland and was sent by his father down to Trinity College Dublin to study for the ministry, the Presbyterian ministry. He and his older brother Jack, who was also studying at Trinity, decided they didn't want to become ministers, so they quite literally ran away to sea. He and his brother first went off to Australia and this trade between the UK, between England and Australia. After several voyages in the 1870s my grandfather jumped ship and joined the Australian army. I was told and that he stayed in Australia for only about six months or so, and then deserted the army and signed onto Interview with Ambassador Keith L. -

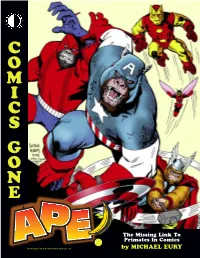

C O M I C S G O N E

C O M I C S G O N E The Missing Link To Primates In Comics by MICHAEL EURY The Avengers TM & © 2007 Marvel Characters, Inc. BARREL OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 5 C H A P T E R 1 BORN TO BE WILD . 6 Girl-Grabbing Gorillas Cover Gallery . .15 Tarzan Through the Years Cover Gallery . 16 Q & Ape with Joe Kubert . 18 Q & Ape with Anne Timmons . 22 C H A P T E R 2 WALKING TALL . 24 Kong-a Line Cover Gallery . 36 Q & Ape with Arthur Adams . 38 Q & Ape with Frank Cho . 44 C H A P T E R 3 MONKEY BUSINESS . 48 Mo’ Monkeys Cover Gallery . 62 Q & Ape with Carmine Infantino . 64 Q & Ape with Tony Millionaire . 68 C H A P T E R 4 GORILLAS IN OUR MIDST . 72 Super-Heroes Battle Super-Gorillas Cover Gallery . 92 Q & Ape with Bob Oksner . 94 Q & Ape with Tim Eldred . 98 C H A P T E R 5 MAKE A MONKEY OUT OF ME . 102 Going Ape Cover Gallery . 118 Q & Ape with Nick Cardy . 120 Q & Ape with Jeff Parker . 124 C H A P T E R 6 WHERE MAN ONCE STOOD SUPREME . 126 Planet of the Apes Cover Gallery . 134 Q & Ape with Doug Moench . 136 Safari-goers and beastmasters never know when they’ll meet a monkey with a mad-on! Watch your step as you bungle into the jungle, where the apes are... BORN TO BE WILD! ave you ever seen a jungle movie that didn’t depict the snorted commands of their middle-aged editors hot to ape H gorilla as really, really angry? That’s fang-snarling, Hollywood’s lucrative jungle craze, tapped the gorilla on the chest-pounding angry.