Travel Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death of Captain Cook in Theatre 224

The Many Deaths of Captain Cook A Study in Metropolitan Mass Culture, 1780-1810 Ruth Scobie PhD University of York Department of English April 2013 i Ruth Scobie The Many Deaths of Captain Cook Abstract This thesis traces metropolitan representations, between 1780 and 1810, of the violent death of Captain James Cook at Kealakekua Bay in Hawaii. It takes an interdisciplinary approach to these representations, in order to show how the interlinked texts of a nascent commercial culture initiated the creation of a colonial character, identified by Epeli Hau’ofa as the looming “ghost of Captain Cook.” The introduction sets out the circumstances of Cook’s death and existing metropolitan reputation in 1779. It situates the figure of Cook within contemporary mechanisms of ‘celebrity,’ related to notions of mass metropolitan culture. It argues that previous accounts of Cook’s fame have tended to overemphasise the immediacy and unanimity with which the dead Cook was adopted as an imperialist hero; with the result that the role of the scene within colonialist histories can appear inevitable, even natural. In response, I show that a contested mythology around Cook’s death was gradually constructed over the three decades after the incident took place, and was the contingent product of a range of texts, places, events, and individuals. The first section examines responses to the news of Cook’s death in January 1780, focusing on the way that the story was mediated by, first, its status as ‘news,’ created by newspapers; and second, the effects on Londoners of the Gordon riots in June of the same year. -

Book of Abstracts

BORDERS AND CROSSINGS TRAVEL WRITING CONFERENCE Pula – Brijuni, 13-16 September 2018 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS BORDERS AND CROSSINGS 2018 International and Multidisciplinary Conference on Travel Writing Pula-Brijuni, 13-16 September 2018 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Published by Juraj Dobrila University of Pula For the Publisher Full Professor Alfio Barbieri, Ph.D. Editor Assistant Professor Nataša Urošević, Ph.D. Proofreading Krešimir Vunić, prof. Graphic Layout Tajana Baršnik Peloza, prof. Cover illustrations Joseph Mallord William Turner, Antiquities of Pola, 1818, in: Thomas Allason, Picturesque Views of the Antiquities of Pola in Istria, London, 1819 Hugo Charlemont, Reconstruction of the Roman Villa in the Bay of Verige, 1924, National Park Brijuni ISBN 978-953-7320-88-1 CONTENTS PREFACE – WELCOME MESSAGE 4 CALL FOR PAPERS 5 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 6 ABSTRACTS 22 CONFERENCE PARTICIPANTS 88 GENERAL INFORMATION 100 NP BRIJUNI MAP 101 Dear colleagues, On behalf of the Organizing Committee, we are delighted to welcome all the conference participants and our guests from the partner institutions to Pula and the Brijuni Islands for the Borders and Crossings Travel Writing Conference, which isscheduled from 13th till 16th September 2018 in the Brijuni National Park. This year's conference will be a special occasion to celebrate the 20thanniversary of the ‘Borders and Crossings’ conference, which is the regular meeting of all scholars interested in the issues of travel, travel writing and tourism in a unique historic environment of Pula and the Brijuni Islands. The previous conferences were held in Derry (1998), Brest (2000), Versailles (2002), Ankara (2003), Birmingham (2004), Palermo (2006), Nuoro, Sardinia (2007), Melbourne (2008), Birmingham (2012), Liverpool (2013), Veliko Tarnovo (2014), Belfast (2015), Kielce (2016) and Aberystwyth (2017). -

John the Painter

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY VOLUME LXIII JANUARY, 1939 NUMBER ONE John the Painter HIS is the tale of an aberrated Scotsman who stepped momen- tarily into the spotlight of history during the American Revo- Tlution, and, for a brief, fantastic space, sent shivers rippling along the spines of Lord North's cabinet, and spread consternation throughout the length and breadth of merry England. He was born plain James Aitken, an unprepossessing infant in the brood of an indigent Edinburgh blacksmith. Dangling from a gibbet in Ports- mouth town, he departed this life, in 1777, famous or infamous, as John the Painter. Twice James Aitken's crimes flared red on the British horizon—an incendiary whose distorted mind interpreted the torch of liberty as literal rather than allegoric -y who set himself, single-handed, to destroy the might of the king's navy. Boasting him- self an agent of the American Congress, this insignificant little Scottish zealot, ere his destructive path ended, had burned to the ground his majesty's rope house in the Portsmouth navy yard, and had started two alarming, if not serious, fires in busy Bristol. Harken, then, to the tale of James Aitken, alias James Hill, other- wise James Hinde, commonly called, as the old court record set forth, John the Painter. Silas Deane's French servant probably eyed with repugnance the shabby little man, who, for the third time, was insisting upon an 2 WILLIAM BELL CLARK January audience with his employer. Twice before the devoted servant, who regarded any Englishman as inimical to his patron's welfare, had dismissed him summarily. -

JAMES CUMMINS Bookseller Catalogue 121 James Cummins Bookseller Catalogue 121 to Place Your Order, Call, Write, E-Mail Or Fax

JAMES CUMMINS bookseller catalogue 121 james cummins bookseller catalogue 121 To place your order, call, write, e-mail or fax: james cummins bookseller 699 Madison Avenue, New York City, 10065 Telephone (212) 688-6441 Fax (212) 688-6192 e-mail: [email protected] jamescumminsbookseller.com hours: Monday – Friday 10:00 – 6:00, Saturday 10:00 – 5:00 Members A.B.A.A., I.L.A.B. front cover: item 20 inside front cover: item 12 inside rear cover: item 8 rear cover: item 19 catalogue photography by nicole neenan terms of payment: All items, as usual, are guaranteed as described and are returnable within 10 days for any reason. All books are shipped UPS (please provide a street address) unless otherwise requested. Overseas orders should specify a shipping preference. All postage is extra. New clients are requested to send remittance with orders. Libraries may apply for deferred billing. All New York and New Jersey residents must add the appropriate sales tax. We accept American Express, Master Card, and Visa. 1 ALBIN, Eleazar. A Natural History of English Insects Illustrated with a Hundred Copper Plates, Curiously Engraven from the Life: And (for those whose desire it) Exactly Coloured by the Author [With:] [Large Notes, and many Curious Observations. By W. Derham]. With 100 hand-colored engraved plates, each accompanied by a letterpress description. [2, title page dated 1720 (verso blank)], [2, dedica- tion by Albin], [4, preface], [4, list of subscribers], [2, title page dated 1724 (verso blank)], [2, dedication by Derham; To the Reader (on verso)], 26, [2, Index], [100] pp. -

Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism Christopher Wachal Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Wachal, Christopher, "Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism" (2011). Dissertations. 181. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Christopher Wachal LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO PAX ECCLESIA: GLOBALIZATION AND CATHOLIC LITERARY MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN ENGLISH BY CHRISTOPHER B. WACHAL CHICAGO, IL MAY 2011 Copyright by Christopher B. Wachal, 2011 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Nothing big worth undertaking is undertaken alone. It would certainly be dishonest for me to claim that the intellectual journey of which this text is the fruition has been propelled forward solely by my own energy and momentum. There have been many who have contributed to its completion – too many, perhaps, to be done justice in so short a space as this. Nonetheless, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to some of those whose assistance I most appreciate. My dissertation director, Fr. Mark Bosco, has been both a guide and an inspiration throughout my time at Loyola University Chicago. -

Oi Duck-Billed Platypus! This July! Text © Kes Gray, 2018

JULY 2019 EDITION Featuring buyer’s recommends and new titles in books, DVD & Blu-ray Cats sit on gnats, dogs sit on logs, and duck-billed platypuses sit on …? Find out in the hilarious Oi Duck-billed Platypus! this July! Text © Kes Gray, 2018. Illustrations © Jim Field, 2018. Gray, © Kes Text NEW for 2019 Oi Duck-billed Platypus! 9781444937336 PB | £6.99 Platypus Sales Brochure Cover v5.indd 1 19/03/2019 09:31 P. 11 Adult Titles P. 133 Children’s Titles P. 180 Entertainment Releases THIS PUBLICATION IS ALSO AVAILABLE DIGITALLY VIA OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.GARDNERS.COM “You need to read this book, Smarty’s a legend” Arthur Smith A Hitch in Time Andy Smart Andy Smart’s early adventures are a series of jaw-dropping ISBN: 978-0-7495-8189-3 feats and bizarre situations from RRP: £9.99 which, amazingly, he emerged Format: PB Pub date: 25 July 2019 unscathed. WELCOME JULY 2019 3 FRONT COVER Oi Duck-billed Platypus! by Kes Gray Age 1 to 5. A brilliantly funny, rhyming read-aloud picture book - jam-packed with animals and silliness, from the bestselling, multi-award-winning creators of ‘Oi Frog!’ Oi! Where are duck-billed platypuses meant to sit? And kookaburras and hippopotamuses and all the other animals with impossible-to-rhyme- with names... Over to you Frog! The laughter never ends with Oi Frog and Friends. Illustrated by Jim Field. 9781444937336 | Hachette Children’s | PB | £6.99 GARDNERS PUBLICATIONS ALSO INSIDE PAGE 4 Buyer’s Recommends PAGE 8 Recall List PAGE 11 Gardners Independent Booksellers Affiliate July Adult’s Key New Titles Programme publication includes a monthly selection of titles chosen specifically for PAGE 115 independent booksellers by our affiliate July Adult’s New Titles publishers. -

White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with Myspace and Facebook.” in Race After the Internet (Eds

CITATION: boyd, danah. (2011). “White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook.” In Race After the Internet (eds. Lisa Nakamura and Peter A. Chow-White). Routledge, pp. 203-222. White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook danah boyd Microsoft Research and HarVard Berkman Center for Internet and Society http://www.danah.org/ In a historic small town outside Boston, I interViewed a group of teens at a small charter school that included middle-class students seeking an alternative to the public school and poorer students who were struggling in traditional schools. There, I met Kat, a white 14-year-old from a comfortable background. We were talking about the social media practices of her classmates when I asked her why most of her friends were moVing from MySpace to Facebook. Kat grew noticeably uncomfortable. She began simply, noting that “MySpace is just old now and it’s boring.” But then she paused, looked down at the table, and continued. “It’s not really racist, but I guess you could say that. I’m not really into racism, but I think that MySpace now is more like ghetto or whatever.” – Kat On that spring day in 2007, Kat helped me finally understand a pattern that I had been noticing throughout that school year. Teen preference for MySpace or 1 Feedback welcome! [email protected] CITATION: boyd, danah. (2011). “White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook.” In Race After the Internet (eds. -

11 — 27 August 2018 See P91—137 — See Children’S Programme Gifford Baillie Thanks to All Our Sponsors and Supporters

FREEDOM. 11 — 27 August 2018 Baillie Gifford Programme Children’s — See p91—137 Thanks to all our Sponsors and Supporters Funders Benefactors James & Morag Anderson Jane Attias Geoff & Mary Ball The BEST Trust Binks Trust Lel & Robin Blair Sir Ewan & Lady Brown Lead Sponsor Major Supporter Richard & Catherine Burns Gavin & Kate Gemmell Murray & Carol Grigor Eimear Keenan Richard & Sara Kimberlin Archie McBroom Aitken Professor Alexander & Dr Elizabeth McCall Smith Anne McFarlane Investment managers Ian Rankin & Miranda Harvey Lady Susan Rice Lord Ross Fiona & Ian Russell Major Sponsors The Thomas Family Claire & Mark Urquhart William Zachs & Martin Adam And all those who wish to remain anonymous SINCE Scottish Mortgage Investment Folio Patrons 909 1 Trust PLC Jane & Bernard Nelson Brenda Rennie And all those who wish to remain anonymous Trusts The AEB Charitable Trust Barcapel Foundation Binks Trust The Booker Prize Foundation Sponsors The Castansa Trust John S Cohen Foundation The Crerar Hotels Trust Cruden Foundation The Educational Institute of Scotland The Ettrick Charitable Trust The Hugh Fraser Foundation The Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund Margaret Murdoch Charitable Trust New Park Educational Trust Russell Trust The Ryvoan Trust The Turtleton Charitable Trust With thanks The Edinburgh International Book Festival is sited in Charlotte Square Gardens by the kind permission of the Charlotte Square Proprietors. Media Sponsors We would like to thank the publishers who help to make the Festival possible, Essential Edinburgh for their help with our George Street venues, the Friends and Patrons of the Edinburgh International Book Festival and all the Supporters other individuals who have donated to the Book Festival this year. -

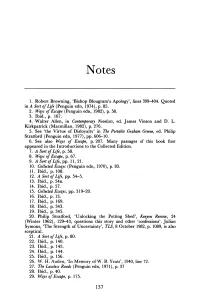

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

2010-2011 Newsletter

Newsletter WILLIAMS G RADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF A RT OFFERED IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CLARK ACADEMIC YEAR 2010–11 Newsletter ••••• 1 1 CLASS OF 1955 MEMORIAL PROFESSOR OF ART MARC GOTLIEB Letter from the Director Greetings from Williamstown! Our New features of the program this past year include an alumni now number well over 400 internship for a Williams graduate student at the High Mu- going back nearly 40 years, and we seum of Art. Many thanks to Michael Shapiro, Philip Verre, hope this newsletter both brings and all the High staff for partnering with us in what promises back memories and informs you to serve as a key plank in our effort to expand opportuni- of our recent efforts to keep the ties for our graduate students in the years to come. We had a thrilling study-trip to Greece last January with the kind program academically healthy and participation of Elizabeth McGowan; coming up we will be indeed second to none. To our substantial community of alumni heading to Paris, Rome, and Naples. An ambitious trajectory we must add the astonishingly rich constellation of art histori- to be sure, and in Rome and Naples in particular we will be ans, conservators, and professionals in related fields that, for a exploring 16th- and 17th-century art—and perhaps some brief period, a summer, or on a permanent basis, make William- sense of Rome from a 19th-century point of view, if I am al- stown and its vicinity their home. The atmosphere we cultivate is lowed to have my way. -

American Revolution End Notes

American Revolution End Notes 1 This article was written by Frank J Rafalko, Chief 12 Letter from George Washington to Governor Jonathan Community Training Branch, National Trumball, November 15, 1775 in which Washington Counterintelligence Center inserted the resolve of Congress he received from John Hancock regarding Church 2 Thomas Hutchinson came from a prominent New England family In 1737, despite his familys 13 This article was written by Frank J Rafalko, Chief, admonishment to him about going into politics, he was Community Training Branch, National elected to the Massachusetts House of Representative Counterintelligence Center He later served as Chief Justice of the colony and then royal governor 14 Col Jacobus Swartwout (d1826), commander of the 3 Francis Bernard was the nephew of Lord Barrington, 2d Dutchess County Regiment of Minute Men the secretary of state for war in London Barrington arranged for Bernard to be appointed as royal governor 15 Johnathan Fowler of New Jersey, but after two years Bernard move to Massachusetts to become royal governor there He was 16 James Kip recalled to London in 1769 17 This article was written by Dan Lovelace, National 4 Dr Benjamin Church Counterintelligence Center 5 AJ Langguth, Patriots The Men Who Started the 18 Carl Van Dorens description of Benedict Arnold in his American Revolution, Simon and Schuster, New York, Secret History of the American Revolution 1988, p 311 19 This article is copyrighted by Eric Evans Rafalko and 6 Edmund R Thompson, ed, Secret New England Spies used with his -

Global Environmental Policy with a Case Study of Brazil

ENVS 360 Global Environmental Policy with a Case Study of Brazil Professor Pete Lavigne, Environmental Studies and Director of the Colorado Water Workshop Taylor Hall 312c Office Hours T–Friday 11:00–Noon or by appointment 970-943-3162 – Mobile 503-781-9785 Course Policies and Syllabus ENVS 360 Global Environmental Policy. This multi-media and discussion seminar critically examines key perspectives, economic and political processes, policy actors, and institutions involved in global environmental issues. Students analyze ecological, cultural, and social dimensions of international environmental concerns and governance as they have emerged in response to increased recognition of global environmental threats, globalization, and international contributions to understanding of these issues. The focus of the course is for students to engage and evaluate texts within the broad policy discourse of globalization, justice and the environment. Threats to Earth's environment have increasingly become globalized and in response to at least ten major global threats—including global warming, deforestation, population growth and persistent organic pollutants—countries, NGOs and corporations have signed hundreds of treaties, conventions and various other types of agreements designed to protect or at least mitigate and minimize damage to the environment. The course provides an overview of developments and patterns in the epistemological, political, social and economic dimensions of global environmental governance as they have emerged over the past three decades. We will also undertake a case study of the interactions of Brazilian environmental policy central to several global environmental threats, including global warming and climate change, land degradation, and freshwater pollution and scarcity. The case study will analyze the intersections of major local, national and international environmental policies.