Chapter 3 the "RED-HOT THRILL"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis and Evaluation of the Acting Career Of

AN ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION OF THE ACTING CAREER OF TALLULAH BANKHEAD APPROVED: Major Professor m Minor Professor Directororf? DepartmenDepa t of Speech and Drama Dean of the Graduate School AN ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION OF THE ACTING CAREER OF TALLULAH BANKHEAD THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Jan Buttram Denton, Texas January, 1970 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. THE BEGINNING OF SUCCESS 1 II. ACTING, ACTORS AND THE THEATRE 15 III. THE ROLES SHE USUALLY SHOULD NOT HAVE ACCEPTED • 37 IV. SIX WITH MERIT 76 V. IN SUMMARY OF TALLULAH 103 APPENDIX 114 BIBLIOGRAPHY. 129 CHAPTER I THE BEGINNING OF SUCCESS Tallulah Bankhead's family tree was filled with ancestors who had served their country; but none, with the exception of Tallulah, had served in the theatre. Both her grandfather and her mother's grandfather were wealthy Alabamians. The common belief was that Tallulah received much of her acting talent from her father, but accounts of her mother1s younger days show proof that both of her parents were vivacious and talented. A stranger once told Tallulah, "Your mother was the most beautiful thing that ever lived. Many people have said you get your acting talent from your father, but I disagree. I was at school with Ada Eugenia and I knew Will well. Did you know that she could faint on 1 cue?11 Tallulahfs mother possessed grace and beauty and was quite flamboyant. She loved beautiful clothes and enjoyed creating a ruckus in her own Southern world.* Indeed, Tallulah inherited her mother's joy in turning social taboos upside down. -

Losing Your Internet: Narratives of Decline Among Long- Time Users

CHAPTER THREE Losing Your Internet: Narratives of Decline among Long- Time Users KEVIN DRISCOLL Annette Markham’s Life Online (1998) documents an historical conjuncture in which the visibility of the Internet in popular culture outpaced hands-on access for most Americans. At the time that Markham was completing her fieldwork, approximately one-third of Americans reported using the Internet, most of whom were white, wealthy, highly educated, and male (Rainie, 2017). Yet, for half a decade, news and entertainment media had been saturated with stories of the Internet as a technical marvel, economic opportunity, social revolution, and moral threat (Schulte, 2013; Streeter, 2017). Every few months, the cover of Time magazine added a new dimension to the Internet story, from the “info highway” in 1993, to the “cyberporn” panic in 1995, dot-com “golden geeks” in 1996, and the “death of privacy” in 1997. Beyond these sensational headlines, friends and coworkers gos- siped about relationships and romances forming online. Early users of the Internet were similarly enthusiastic and many shared a sense that computer-mediated com- munication might transform the social world. Even Markham described her initial observations of the internet and its growing user population as “astounding” and “extraordinary” (1998, pp. 16–17). At the turn of the century, the Internet seemed charged with unknown possibility. Twenty years later, the structure of feeling that characterized early encoun- ters with the Internet has changed. For millions of people, computer-mediated communication is now an unremarkable aspect of everyday life. In comparison to the fantastical multi-user environments that Markham described in 1998, typical uses of the internet in 2017 seem quite dull: reading the news, solving a crossword 26 | KEVIN DRISCOLL puzzle, shopping for household goods, or arranging meetings with coworkers. -

Matrix Become a Fan Without Being Irrevocably Cut Off from Any SF Roots

£1.25 110 NewsCetter Of tile Brittsll Science Yiction Association Ye6ruar9 - Marcil 1994 Morrix110 Datarife Determinants It seems to make more Sense to start a new year in February when the Membership weather is once more becoming civilised, rather than having it This costs £15 per year (UK and EC). immediately adjacent to the glullony and indulgence of Christmas. A British winter seems to be an endless tunnel of low-level misery and New members: Alison Cook, 27 Albemarle Drive. Grove, Wantage. dampness, so the first appearance of Ihe sun produces a primitive Oxon aXIl ON8 resurgence of joy. As the skeleton trees slowly blur into buds and the ground changes from mud to mud with stalks, there seems more point Renewals: Keith Freeman, 269 Wykeham Road, Reading RG6 IPL to life: and, perhaps, there may seem to be more to life than reading SF. USA: Cy Chauvin. 14248 Wilfred Street, Detroit. M148213, USA Unlike the metamorphosis from larva to dragon fly, an SF reader can Matrix become a fan without being irrevocably cut off from any SF roots. A fan will almost by definition stan as an SF reader who wishes to take Jenny and Steve Glover. 16 Aviary Place, Leeds LSl2 2NP a mOTe active role in the SF community. I'm not entirely convinced. Tel: 0532 791264 though, that people deliberately set out to become fans, There are a whole series of circumstances which seem to be coincidences and Vector which cascade onto the unwary reader but which will fail to activate anyone unless some spark of curiosity or sense of wonder gets ignited Catie Cary. -

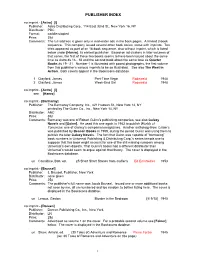

Publisher Index

PUBLISHER INDEX no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] Publisher: Astro Distributing Corp., 114 East 32nd St., New York 16, NY Distributor: PDC Format: saddle-stapled Price: 35¢ Comments: The full address is given only in mail-order ads in the back pages. A limited 2-book sequence. This company issued several other book series, some with imprints. Ten titles appeared as part of an 18-book sequence, also without imprint, which is listed below under [Hanro], its earliest publisher. Based on ad clusters in later volumes of that series, the first of these two books seems to have been issued about the same time as Astro #s 16 - 18 and the second book about the same time as Quarter Books #s 19 - 21. Number 1 is illustrated with posed photographs, the first volume from this publisher’s various imprints to be so illustrated. See also The West in Action. Both covers appear in the Bookscans database. 1 Clayford, James Part-Time Virgin Rodewald 1948 2 Clayford, James W eek -End Girl Rodewald 1948 no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] see [Hanro] no imprint - [Barmaray] Publisher: The Barmaray Company, Inc., 421 Hudson St., New York 14, NY printed by The Guinn Co., Inc., New York 14, NY Distributor: ANC Price: 35¢ Comments: Barmaray was one of Robert Guinn’s publishing companies; see also Galaxy Novels and [Guinn]. He used this one again in 1963 to publish Worlds of Tomorrow, one of Galaxy’s companion magazines. Another anthology from Collier’ s was published by Beacon Books in 1959, during the period Guinn was using them to publish the later Galaxy Novels. -

Wolverine Nº 131 Viñeta De Selección: Swamp Thing Del Nueve Al Siete: Daredevil ¡¡¡Y Mucho Más!!!

El Solipsista Ilustrado: Wolverine nº 131 Viñeta de Selección: Swamp Thing Del Nueve al Siete: Daredevil ¡¡¡Y mucho más!!! El peor e-zine que he leído sin duda EDITORIAL A NEW HOPE El profesor Charles Xavier antes que el telépata más Calabozo del Androide Nº 0 poderoso del mundo, antes que el fundador de los X- Mayo Men, es un tipo con un sueño, un proyecto o ideal que 2003 tiene tal fuerza que lo han hecho suyo personajes tan distintos como lo pueden ser Cíclope y Wolverine. Director / Editor Conozco a un visionario llamado Luis Saavedra que, Sergio Alejandro Amira como Xavier, posee un sueño igual de contagioso, el cual se ha corporizado en un fanzine de ciencia ficción Diagramación y Diseño y fantasía llamado Fobos. Sergio Alejandro Amira exxComo muchos de los colaboradores me involucré primeramente con Fobos en calidad de lector, y terminé Portada como diagramador y columnista, funciones que asumí Matt Groening desde el nº 15 en adelante. En dicha oportunidad se suscitó un problema recurrente: faltaban dos páginas ya Columnistas que el número total de estas siempre debe ser divisible Gabriel Álvarez por cuatro. Le sugerí entonces a Carlos Andrade, el Sergio Alejandro Amira editor de turno, que incluyera un artículo de cómics en Remigio Aras calidad de relleno a lo cual él accedió. ¿Lo escribes Luis Saavedra tú?, me dijo, No, respondí, ya tengo suficiente trabajo diagramando y corrigiendo los textos, pero sé Contacto de alguien que podría ayudarnos: mi primo Remigio [email protected] Aras. El artículo de Remigio llegó a tiempo pero no estaba muy bien redactado por lo que Carlos tuvo que meterle mano y terminaron firmándolo a medias. -

Censorship of Publications Acts, 1929 to 1967

CENSORSHIP OF PUBLICATIONS ACTS, 1929 TO 1967 REGISTER OF PROHIBITED PUBLICATIONS 1. Alphabetical list of books prohibited on the ground that they were indecent or obscene (correct to 31st December, 2012). 2. Alphabetical list of books prohibited on the ground(s) that they were indecent or obscene and/or that they advocate the procurement of abortion or miscarriage or the use of any method, treatment or appliance for the purpose of such procurement (correct to 31st December, 2012). 3. Alphabetical list of prohibited Periodical Publications (as on 31st December, 2012). __________________________________ Published by the Censorship Board in accordance with directions of the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform pursuant to sub-section (5) of section 16 of the Censorship of Publications Act, 1946 _______________________________________ DUBLIN: IMPORTANT The Register of prohibited books is in two Parts Part 1 contains particulars of books prohibited on the ground that they were indecent or obscene. The prohibition order in respect of any book named in Part 1 will cease to have effect on the 31st December following the twelfth anniversary of the date it was published in the Iris Oifigiúil (if it is not revoked by the Appeal Board before that). Where two or more prohibition orders refer to the same book, they will all cease to have effect when the one first made so ceases. Part II contains particulars of books prohibited on the ground(s) that they were indecent or obscene and/or that they advocate the procurement of abortion or miscarriage or the use of any method, treatment or appliance for the purpose of such procurement. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

Roy Thomas’ All-Star-Struck SEE? WE TOLD YOU $ Comics Fanzine THERE’D BE ANOTHER 8.95 ISSUE STARRING THE In the USA JUSTICEJUSTICE SOCIETYSOCIETY TM OFOF AMERICAAMERICA No.121 November 2013 JOHNNY THUNDER! THE ATOM! JUSTICE SOCIETY! JOHNWRITER/CO-CREATOR LENB. WENTWORTH! SANSONE! OF INKER/CO-CREATOR OF BERNARD SACHS! INKER OF 1948-1951 1 0 SPECIAL! Justice Society of America TM & © DC Comics. 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 121 / November 2013 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek Contents William J. Dowlding Cover Artists Writer/Editorial: “…And All The Stars Looked Down”. 2 Shane Foley John B. Wentworth—All-American Thunderbolt . 3 (after Irwin Hasen) Cover Colorist Daughter Rebecca Wentworth tells Richard Arndt about the creator of “Johnny Thunder,” “Sargon the Sorcerer,” & “The Whip.” Tom Ziuko Special A/E Interlude: “The Will Of William Wilson” . 18 With Special Thanks to: Splitting The Atom—Three Ways! . 21 Heidi Amash Mark Lewis Richard J. Arndt Jim Ludwig Mrs. Emily Sokoloff & Maggie Sansone talk to Shaun Clancy about Leonard Sansone— Bob Bailey Ed Malsberg inker/co-creator of “The Atom”—and about co-creators Ben Flinton and Bill O’Connor. Rod Beck Doug Martin “The Life Of A Freelancer… Is Always Feast Or Famine” . 40 Judy Swayze Bruce Mason Blackman Mike Lynch Bernice Sachs-Smollet to Richard Arndt about her late husband, JSA/JLA artist Bernard Sachs. -

X-MEN $ Featuring Their First- 8.95 Decade Definers: in the USA LEE • KIRBY • ROTH No.120 THOMAS • ADAMS • HECK Sept

Roy Thomas’ X-uberant Comics Fanzine A HALF-CENTURY SALUTE TO THE TM X-MEN $ Featuring Their First- 8.95 Decade Definers: In the USA LEE • KIRBY • ROTH No.120 THOMAS • ADAMS • HECK Sept. TUSKA • FRIEDRICH 2013 DRAKE • BUSCEMA KANE • COLAN COCKRUM NOSTALGICNOTE: KA-ZAR’S PROBABLY IN THIS ISSUE, TOO––BUT DON’T BLINK, OR YOU’LL MISS HIM! PLUS: X-MEN TM & ©Marvel Characters, Inc. 0 8 ED 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 120 / September 2013 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor If you’re viewing a Digital P.C. Hamerlinck Edition of this publication, Comic Crypt Editor PLEASE READ THIS: This is copyrighted material, NOT intended Michael T. Gilbert for downloading anywhere except our Editorial Honor Roll website. If you downloaded it from another website or torrent, go ahead and read it, and if you decide to keep it, DO THE Jerry G. Bails (founder) RIGHT THING and buy a legal download, or a printed copy (which entitles you to the Ronn Foss, Biljo White free Digital Edition) at our website or your local comic book shop. Otherwise, DELETE Mike Friedrich IT FROM YOUR COMPUTER and DO Proofreaders NOT SHARE IT WITH FRIENDS OR POST IT ANYWHERE. If you enjoy our publications enough to download them, Rob Smentek please pay for them so we can keep producing ones like this. Our digital William J. Dowlding editions should ONLY be downloaded at Cover Artists www.twomorrows.com Jack Kirby & Chic Stone Contents Cover Colorist Writer/Editorial: Not X-actly X-static, But.. -

This Dissertation Has Been 61—5100 M Icrofilm Ed Exactly As Received

This dissertation has been 61—5100 microfilmed exactly as received LOGAN, Winford Bailey, 1919- AN INVESTIGATION OF THE THEME OF THE NEGATION OF LIFE IN AMERICAN DRAMA FROM WORLD WAR H TO 1958. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 Speech — Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan AN INVESTIGATION OF THE THSiE OF THE NEGATION OF LIFE IN AMERICAN DRAMA FROM WORLD WAR II TO 1958 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Winford Bailey Logan* B.A.* M.A. The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Adviser Department of Speech CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. A BACKGROUND OF PHILOSOPHICAL NEGATION 5 III. A BASIS OF JUDGMENT: THE CHARACTERISTICS AND 22 SYMPTOMS OF LIFE NEGATION IV. SERIOUS DRAMA IN AMERICA PRECEDING WORLD WAR II i+2 V. THE PESSIMISM OF EUGENE O'NEILL AND AN ANALYSIS 66 OF HIS LATER PLAYS VI. TENNESSEE WILLIAMS: ANALYSES OF THE GLASS MENAGERIE. 125 A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE AND CAMINO REAL VII. ARTHUR MILLER: ANALYSES OF DEATH OF A SALESMAN 179 AND A VIEW FRCM THE BRIDGE VIII. THE PLAYS OF WILLIAM INGE 210 IX. THE USE OF THE THEME OF LIFE NEGATION BY OTHER 233 AMERICAN WRITERS OF THE PERIOD X. CONCLUSIONS 271 BIBLIOGRAPHY 289 AUTOBIOGRAPHY 302 ii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Critical comment pertaining to present-day American theatre frequently has included allegations that thematic emphasis seems to lie in the areas of negation. Such attacks are supported by references to our over-use of sordidity, to the infatuation with the psychological theme and the use of characters who are emotionally and mentally disturbed, and to the absence of any element of the heroic which is normally acknowledged to be an integral portion of meaningful drama. -

Adapting the Graphic Novel Format for Undergraduate Level Textbooks

ADAPTING THE GRAPHIC NOVEL FORMAT FOR UNDERGRADUATE LEVEL TEXTBOOKS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian M. Kane, M.A. Graduate Program in Arts Administration, Education, and Policy The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Professor Candace Stout, Advisor Professor Clayton Funk Professor Shari Savage Professor Arthur Efland Copyright by Brian M. Kane 2013 i ABSTRACT This dissertation explores ways in which the graphic narrative (graphic novel) format for storytelling, known as sequential art, can be adapted for undergraduate-level introductory textbooks across disciplines. Currently, very few graphic textbooks exist, and many of them lack the academic rigor needed to give them credibility. My goal in this dissertation is to examine critically both the strengths and weaknesses of this art form and formulate a set of standards and procedures necessary for developing new graphic textbooks that are scholastically viable for use in college-level instruction across disciplines. To the ends of establishing these standards, I have developed a four-pronged information-gathering approach. First I read as much pre factum qualitative and quantitative data from books, articles, and Internet sources as possible in order to establish my base of inquiry. Second, I created a twelve-part dissertation blog (graphictextbooks.blogspot.com) where I was able to post my findings and establish my integrity for my research among potential interviewees. Third, I interviewed 16 professional graphic novel/graphic textbook publishers, editors, writers, artists, and scholars as well as college professors and librarians. Finally, I sent out an online survey consisting of a sample chapter of an existing graphic textbook to college professors and asked if the content of the source material was potentially effective for their own instruction in undergraduate teaching. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items FAMOUS AMERICAN ILLUSTRATORS On our Cover Specially Priced SOI file copies from 1997! Our NAUGHTY AND NICE The Good Girl Art of Highest Recommendation. By Bruce Timm Publisher Edition Arpi Ermoyan. Fascinating insights New Edition. Special into the lives and works of 82 top exclusive Publisher’s artists elected to the Society of Hardcover edition, 1500. Illustrators Hall of Fame make Highly Recommended. this an inspiring reference and art An extensive survey of book. From illustrators such as N.C. Bruce Timm’s celebrated Wyeth to Charles Dana Gibson to “after hours” private works. Dean Cornwell, Al Parker, Austin These tastefully drawn Briggs, Jon Whitcomb, Parrish, nudes, completed purely for Pyle, Dunn, Peak, Whitmore, Ley- fun, are showcased in this endecker, Abbey, Flagg, Gruger, exquisite new release. This Raleigh, Booth, LaGatta, Frost, volume boasts over 250 Kent, Sundblom, Erté, Held, full-color or line and pencil Jessie Willcox Smith, Georgi, images, each one full page. McGinnis, Harry Anderson, Bar- It’s all about sexy, nubile clay, Coll, Schoonover, McCay... girls: partially clothed or fully nude, of almost every con- the list of greats goes on and on. ceivable description and temperament. Girls-next-door, Society of Illustrators, 1997. seductresses, vampires, girls with guns, teases...Timm FAMAMH. HC, 12x12, 224pg, FC blends his animation style with his passion for traditional $40.00 $29.95 good-girl art for an approach that is unmistakably all his JOHN HASSALL own. Flesk, 2021. Mature readers. NOTE: Unlike the The Life and Art of the Poster King first, Timm didn’t sign this second printing. -

LEONARD STARR Vol

Roy Tho mas ’Thunderclap of a Comics Fan zine FEATURING: AN FOUR-COLOR FIST-FEST! $ In8 th.e9 U5SA No.110 June 2012 . s c i m o C C D 2 1 0 2 © & M T 6 o 0 g o l 5 ” ! m 3 a z 6 a h 7 S 7 “ 2 & s 8 e o 5 r e 6 h 2 ALSO: m 8 a z a h S 1 LEONARD STARR Vol. 3, No. 110 / June 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreader Rob Smentek Cover Artist Emilio Squeglio (pencils) & Joe Giella (inks) Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Guest Writer/Editorial: Emilio Squeglio (1927-2012) . 2 Jack Adams Paul Levitz “I Think I Worked For Every [Comics] House In The City” . 3 Heidi Amash Barbara Levy Ger Apeldoorn Alan Light Part I of Jim Amash’s decades-spanning interview with noted comics artist Leonard Starr. Richard Arndt Jim Ludwig “The Will Of William Wilson” Lost Pages—In Color! . 23 Jean Bails Dick Lupoff Mike W. Bar Pat Lupoff Continued from last issue, here’s the final pair of pages from the unpublished JSA chapter. Rod Beck Will Meugniot Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! The Covers That Never Were! . 25 John Benson Brian K. Morris Jerry Bingham Will Murray Michael T. Gilbert reinterprets Simon & Kirby and Carl Pfeufer (or is it Bill Everett?).