Mount Zirkel Herd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FS Region 2 Snowmobile Trespass Strategy

Rocky Mountain Region Information and Education Strategy For The Prevention of Snowmobile Trespass In Wilderness Third Edition January 2004 - -1 Table of Contents Page I. Problem Statement 1 II. Current Situation 1 III. Current Direction 3 IV. Implementation and Responsibilities 3 V. Monitoring and Reporting 4 VI. Using the Appendices and Tool Kit 4 VII. Appendices A. Excerpts from the Wilderness Act of 1964 6 B. Selected References from the Code of Federal Regulations 7 C. Selected References from Forest Service Manual 2320 8 D. Patrol Ideas 11 E. Potential Cooperators/Contacts for Reaching Local Users 13 F. Potential Cooperators/Contacts for Reaching Non-local Users 15 G. In-house I&E Ideas 17 H. Suggested Actions for Dealing With Intentional Trespass 18 I. Tool and Techniques - Law Enforcement and the “Authority Of The Resource" 19 J. What Harm Is There in Operating My Snowmobile in Wilderness? 25 K. Why is Wilderness Closed to Motorized and Mechanical Travel? 26 L. State Registration Agencies, State Snowmobile Associations and Snowmobile Clubs 27 M. Annual Monitoring Report 35 VIII. Tool Kit 38 1 - -1 I. Problem Statement The Wilderness Act of 1964 first created Congressionally designated wilderness. The Act stated that "In order to assure that an increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization, does not occupy and modify all areas within the United States ... it is hereby declared to be the policy of Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness". The Act defined wilderness as having outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation. -

Mitteilungen 29

MITTEILUNGEN 29. Jahrgang / Heft 1-2019 / kostenlos „Leipziger Kletterschule“ 100 Jahre Ostbruch Brandis 7-Brüche-Wandertag Flyer zum Jubiläum (Beilage im Heft) Wild, Wilder, Wilderness Trekking in den Bergen Colorados Iran Skitour zum Damawand 1 DAV MITTEILUNGEN | AUS DER GESCHÄFTSSTELLE 2 Vorwort Winter ohne Leipzig Den Ein oder Anderen könnte es freuen, dass dieser Winter weite Teile Deutschlands und Ös- doch einige der spannendsten Geschichten bereit, terreich voll im Griff hatte und zum Schnee- die ihr in diesem Heft nacherleben könnt. Eine schuhwandern und Skitouren gehen eingeladen Skitour im Iran, eine Wintertour von Thomas aber hat. Wer jedoch nicht geplant hatte einmal in die auch eine Trekking-Reise in den eher wärmeren Alpen zu fahren, der blieb vom Schnee verschont. Gefilden von Colorado (Teil1) werden euch diese In Leipzig hatte man wie immer das Gefühl un- Ausgabe versüßen. Ebenso fiebere ich bereits den ter einer Glocke zu leben die den Schnee abfängt. ersten warmem Sonnenstrahlen und Tagen am Seit einigen Jahren erlebe ich den Winter hier Fels entgegen. Über Ostern geht es sicher wieder eher als verspäteten Herbst mit reichlich Regen, für ein paar Tage nach Tirol, um einige Projekte Tee und intensivem Hallentraining. Für jemanden vom letzten Jahr in der Ehnbachklamm anzuge- wie mich, der seine Kindheit im Südharz verbracht hen. Einer der schönsten Kletterspots die ich bis- hat, ist das schon etwas gewöhnungsbedürftig. her besuchen durfte. Um wenigstens einen Hauch von Wintergefühl Anlässlich des 150 Jubiläums des Deutschen Al- zu bekommen, muss ich hier schon in den Zug penvereines und auch der Sektion Leipzig, freue steigen. Da freue ich mich umso mehr von den ich mich in diesem Jahr zudem besonders auf die Menschen zu lesen, die sich trotz der hiesigen Jubiläumsfeier am 31. -

Estimating Natural Visibility Conditions Under the Regional Haze Rule EPA-454/B-03-005 September 2003

Guidance for Estimating Natural Visibility Conditions Under the Regional Haze Rule EPA-454/B-03-005 September 2003 Guidance for Estimating Natural Visibility Conditions Under the Regional Haze Program Contract No. 68-D-02-0261 Work Order No. 1-06 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards Emissions, Monitoring and Analysis Division Air Quality Trends Analysis Group Research Triangle Park, NC DISCLAIMER This report is a work prepared for the United States Government by Battelle. In no event shall either the United States Government or Battelle have any responsibility or liability for any consequences of any use, misuse, inability to use, or reliance upon the information contained herein, nor does either warrant or otherwise represent in any way the accuracy, adequacy, efficacy, or applicability of the contents hereof. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Environmental Protection Agency wishes to acknowledge the assistance and input provided by the following advisors in the preparation of this guidance document: Rodger Ames, National Park Service, Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere (CIRA); Shao-Hang Chu, USEPA; Rich Damberg, USEPA; Tammy Eagan, Florida Dept. of Environmental Protection; Neil Frank, USEPA; Eric Ginsburg, USEPA; Dennis Haddow, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Ann Hess, Colorado State University; Hari Iyer, Dept. of Statistics, Colorado State University; Mike Koerber, Lake Michigan Air Directors Consortium; Bill Leenhouts, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; William Malm, National Park Service (CIRA); Debbie Miller, National Park Service; Tom Moore , Western Regional Air Partnership; Janice Peterson, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; Marc Pitchford, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Air Resources Laboratory; Rich Poirot, State of Vermont, Dept. -

Historical Range of Variability and Current Landscape Condition Analysis: South Central Highlands Section, Southwestern Colorado & Northwestern New Mexico

Historical Range of Variability and Current Landscape Condition Analysis: South Central Highlands Section, Southwestern Colorado & Northwestern New Mexico William H. Romme, M. Lisa Floyd, David Hanna with contributions by Elisabeth J. Bartlett, Michele Crist, Dan Green, Henri D. Grissino-Mayer, J. Page Lindsey, Kevin McGarigal, & Jeffery S.Redders Produced by the Colorado Forest Restoration Institute at Colorado State University, and Region 2 of the U.S. Forest Service May 12, 2009 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY … p 5 AUTHORS’ AFFILIATIONS … p 16 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS … p 16 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION A. Objectives and Organization of This Report … p 17 B. Overview of Physical Geography and Vegetation … p 19 C. Climate Variability in Space and Time … p 21 1. Geographic Patterns in Climate 2. Long-Term Variability in Climate D. Reference Conditions: Concept and Application … p 25 1. Historical Range of Variability (HRV) Concept 2. The Reference Period for this Analysis 3. Human Residents and Influences during the Reference Period E. Overview of Integrated Ecosystem Management … p 30 F. Literature Cited … p 34 CHAPTER II. PONDEROSA PINE FORESTS A. Vegetation Structure and Composition … p 39 B. Reference Conditions … p 40 1. Reference Period Fire Regimes 2. Other agents of disturbance 3. Pre-1870 stand structures C. Legacies of Euro-American Settlement and Current Conditions … p 67 1. Logging (“High-Grading”) in the Late 1800s and Early 1900s 2. Excessive Livestock Grazing in the Late 1800s and Early 1900s 3. Fire Exclusion Since the Late 1800s 4. Interactions: Logging, Grazing, Fire, Climate, and the Forests of Today D. Summary … p 83 E. Literature Cited … p 84 CHAPTER III. -

COLORADO CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL COALITION VISIT COLORADO! Day & Overnight Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail

CONTINENTAL DIVIDE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL DAY & OVERNIGHT HIKES: COLORADO CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL COALITION VISIT COLORADO! Day & Overnight Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail THE CENTENNIAL STATE The Colorado Rockies are the quintessential CDT experience! The CDT traverses 800 miles of these majestic and challenging peaks dotted with abandoned homesteads and ghost towns, and crosses the ancestral lands of the Ute, Eastern Shoshone, and Cheyenne peoples. The CDT winds through some of Colorado’s most incredible landscapes: the spectacular alpine tundra of the South San Juan, Weminuche, and La Garita Wildernesses where the CDT remains at or above 11,000 feet for nearly 70 miles; remnants of the late 1800’s ghost town of Hancock that served the Alpine Tunnel; the awe-inspiring Collegiate Peaks near Leadville, the highest incorporated city in America; geologic oddities like The Window, Knife Edge, and Devil’s Thumb; the towering 14,270 foot Grays Peak – the highest point on the CDT; Rocky Mountain National Park with its rugged snow-capped skyline; the remote Never Summer Wilderness; and the broad valleys and numerous glacial lakes and cirques of the Mount Zirkel Wilderness. You might also encounter moose, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, marmots, and pika on the CDT in Colorado. In this guide, you’ll find Colorado’s best day and overnight hikes on the CDT, organized south to north. ELEVATION: The average elevation of the CDT in Colorado is 10,978 ft, and all of the hikes listed in this guide begin at elevations above 8,000 ft. Remember to bring plenty of water, sun protection, and extra food, and know that a hike at elevation will likely be more challenging than the same distance hike at sea level. -

Appendix C - Roadless Areas

Appendix C - Roadless Areas Purpose The purpose of this appendix is to describe roadless areas and the analysis factors used in evaluating individual roadless areas on the Routt National Forest. It includes a description of the physical and biological features, primitive recreation and education opportunities, resources, and present management situation for each area. Background Roadless Area Review and Evaluation In 1970, the Forest Service studied all administratively designated primitive areas and inventoried and reviewed all roadless areas in the National Forest System greater than 5,000 acres. This study was known as the Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE). RARE was halted in 1972 due to legal challenge. RARE identified 711,043 acres of roadless area on the Routt National Forest. In 1977, the Forest Service began another nation-wide Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE II) to identify roadless and undeveloped areas within the National Forest System that were suitable for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System. Twenty nine areas, totalling 566,756 acres, were inventoried on the Routt National Forest (including the Middle Park Ranger District of the Arapaho-Roosevelt National Forest). As a result of RARE II, four areas on the forest - Williams Fork, St. Louis Peak, Service Creek, and Davis Peak - were administratively designated as Further Planning Areas (FPA). This further planning area designation meant that more information was needed before the Forest Service would recommend any of these areas to Congress for wilderness designation. In January 1979, the Forest Service issued nationally a Final Environmental Impact Statement documenting a review of 62 million acres of roadless and undeveloped areas within the 191-million-acre National Forest System. -

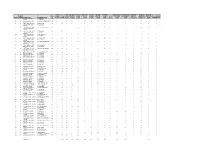

Region Forest Number Forest Name Wilderness Name Wild

WILD FIRE INVASIVE AIR QUALITY EDUCATION OPP FOR REC SITE OUTFITTER ADEQUATE PLAN INFORMATION IM UPWARD IM NEEDS BASELINE FOREST WILD MANAGED TOTAL PLANS PLANTS VALUES PLANS SOLITUDE INVENTORY GUIDE NO OG STANDARDS MANAGEMENT REP DATA ASSESSMNT WORKFORCE IM VOLUNTEERS REGION NUMBER FOREST NAME WILDERNESS NAME ID TO STD? SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE FLAG SCORE SCORE COMPL FLAG COMPL FLAG SCORE USED EFF FLAG 02 02 BIGHORN NATIONAL CLOUD PEAK 080 Y 76 8 10 10 6 4 8 10 N 8 8 Y N 4 N FOREST WILDERNESS 02 03 BLACK HILLS NATIONAL BLACK ELK WILDERNESS 172 Y 84 10 10 4 10 10 10 10 N 8 8 Y N 4 N FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP FOSSIL RIDGE 416 N 59 6 5 2 6 8 8 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP LA GARITA WILDERNESS 032 Y 61 6 3 10 4 6 8 8 N 6 6 Y N 4 Y GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP LIZARD HEAD 040 N 47 6 3 2 4 6 4 6 N 6 8 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP MOUNT SNEFFELS 167 N 45 6 5 2 2 6 4 8 N 4 6 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP POWDERHORN 413 Y 62 6 6 2 6 8 10 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP RAGGEDS WILDERNESS 170 Y 62 0 6 10 6 6 10 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP UNCOMPAHGRE 037 N 45 6 5 2 2 6 4 8 N 4 6 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP WEST ELK WILDERNESS 039 N 56 0 6 10 6 6 4 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 06 MEDICINE BOW-ROUTT ENCAMPMENT RIVER 327 N 54 10 6 2 6 6 8 6 -

Geology and Coal Resources Op North Park, Colorado

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIBECTOR' 596 GEOLOGY AND COAL RESOURCES OP NORTH PARK, COLORADO BY A. L. BEEKLY WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1915 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction _ ______ _,___________ 7 Location and area__ _ _ _____. __________1___ 7 Accessibility_________________________________ 8 Explorations in the region________________________ 8 Preparation of the map___________________________ 10 Base map_.______________________________ 10 ' Field work_______________________________ 10 Office work______________._________ __ 11 Acknowledgments_______________________________ 11 Geography ______________ ______________________ 12 Relief______________________________________ 12 Major features..____________.________________ 12 Medicine Bow Range_______.________ ______ 12 Park Range____________________________ 13 Continental Divide____________.___________ 13 Floor of the park____________ '._.___________ 13 Minor features________________:_. ______ 14 Drainage___________________ ______________ 16 Settlement__________i_______________________ 18 Stratigraphy __________ __________.___________ 19 Sedimentary rocks ______________________________ 19 Age and correlation.. ______!____ .___________ 19 Geologic section________________._________'_ 20 Carboniferous (?) system_______________________ 21 Pennsylvanfan or Permian (?) series______________ 21 Distribution and character_____.___________ 21 Stratigraphic relations________.___________ 21 Fossils_____________________________ 22 Triassic (?) -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest State National Wilderness Area NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Alabama Cheaha Wilderness Talladega National Forest 7,400 0 7,400 Dugger Mountain Wilderness** Talladega National Forest 9,048 0 9,048 Sipsey Wilderness William B. Bankhead National Forest 25,770 83 25,853 Alabama Totals 42,218 83 42,301 Alaska Chuck River Wilderness 74,876 520 75,396 Coronation Island Wilderness Tongass National Forest 19,118 0 19,118 Endicott River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 98,396 0 98,396 Karta River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 39,917 7 39,924 Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tongass National Forest 979,079 21,741 1,000,820 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 654 654 Kuiu Wilderness Tongass National Forest 60,183 15 60,198 Maurille Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 4,814 0 4,814 Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Tongass National Forest 2,144,010 235 2,144,245 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Tongass National Forest 46,758 0 46,758 Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 23,083 41 23,124 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Russell Fjord Wilderness Tongass National Forest 348,626 63 348,689 South Baranof Wilderness Tongass National Forest 315,833 0 315,833 South Etolin Wilderness Tongass National Forest 82,593 834 83,427 Refresh Date: 10/14/2017 -

Grand County Master Plan Was Adopted by the Grand County Planning Commission on ______, 2011 by Resolution No

Grand County Department of Planning and Zoning February 9, 2011 GRAND COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION Gary Salberg, Chairman Lisa Palmer, Vice-Chair Sally Blea Steven DiSciullo George Edwards Karl Smith Ingrid Karlstrom Mike Ritschard Sue Volk GRAND COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS James L. Newberry, Commissioner District I Nancy Stuart, Commissioner District II Gary Bumgarner, Commissioner District III The Grand County Master Plan was adopted by the Grand County Planning Commission on __________________, 2011 by Resolution No. ______________. The Master Plan was prepared by: Grand County Department of Planning & Zoning, 308 Byers Ave, PO Box 239, Hot Sulphur Springs, CO 80451 (970)725-3347 and Belt Collins 4909 Pearl East Circle Boulder, CO 80301 (303)442-4588 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .....................................................................................................................................iv Chapter 1 Planning Approach & Context .................................................................................................1 Chapter 2 Building a Planning Foundation .............................................................................................17 Chapter 3 Plan Elements ...........................................................................................................................32 Chapter 4 Growth Areas, Master Plan Updates & Amendments ..........................................................51 Appendix A Growth Area Maps ...............................................................................................................53 -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Rocky Mountain Region 1997-1999

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Rocky Mountain Region 1997-1999 United States Renewable Rocky Department of Resources Mountain Agriculture Forest Health Region Management 2 FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION 1997-1999 by The Forest Health Management Staff Edited by Jeri Lyn Harris, Michelle Frank, and Susan Johnson December 2001 USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region Renewable Resources, Forest Health Management P.O. Box 25127 Lakewood, Colorado 80225-5127 Cover: Aerial photograph taken by Robert D. Averill on October 29, 1997, just days after a blowdown event occurred on the Routt National Forest. The picture was taken looking east toward a blowdown area that straddles both the Mt. Zirkel Wilderness and the Routt National Forest. “The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternate means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity employer.” Maps in this product are reproduced from geospatial information prepared by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. GIS data and product accuracy may vary.