The Rockies of Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

TOWN BOARD REGULAR MEETING October 28, 2019 - 7:00 PM Town Board Chambers, 301 Walnut Street, Windsor, CO 80550

TOWN BOARD REGULAR MEETING October 28, 2019 - 7:00 PM Town Board Chambers, 301 Walnut Street, Windsor, CO 80550 AGENDA A. CALL TO ORDER 1. Roll Call 2. Pledge of Allegiance 3. Review of Agenda by the Board and Addition of Items of New Business to the Agenda for Consideration 4. Proclamation • National Adoption Day Proclamation 5. Board Liaison Reports • Town Board Member Baker - Tree Board, Historic Preservation Commission • Town Board Member Wilson - Parks, Recreation and Culture Advisory Board; Poudre River Trail Corridor • Mayor Pro Tem Bennett - Water and Sewer Board • Town Board Member Rennemeyer - Chamber of Commerce • Town Board Member Jones - Windsor Housing Authority; Great Western Trail Authority • Town Board Member Sislowski - Clearview Library Board; Planning Commission • Mayor Melendez - Downtown Development Authority; North Front Range/MPO 6. Public Invited to be Heard Individuals wishing to participate in Public Invited to be Heard (non-agenda item) are requested to sign up on the form provided in the foyer of the Town Board Chambers. When you are recognized, step to the podium, state your name and address then speak to the Town Board. Individuals wishing to speak during the Public Invited to be Heard or during Public Hearing proceedings are encouraged to be prepared and individuals will be limited to three (3) minutes. Written comments are welcome and should be given to the Deputy Town Clerk prior to the start of the meeting. B. CONSENT CALENDAR 1. Minutes of the October 14, 2019 Regular Town Board Meeting 2. Resolution No. 2019-71 - A Resolution Approving an Intergovernmental Agreement for Assistance with Great Outdoors Colorado Funding for the Completion of the Poudre River Trail, Between the Town of Windsor, Colorado and Larimer County - W. -

Subgrid Variability of Snow Water Equivalent at Operational Snow Stations in the Western USA

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. 27, 2383–2400 (2013) Published online 24 May 2012 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/hyp.9355 Subgrid variability of snow water equivalent at operational snow stations in the western USA Leah Meromy,1* Noah P. Molotch,1,2 Timothy E. Link,3 Steven R. Fassnacht4 and Robert Rice5 1 Department of Geography, Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA 2 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 3 Department of Forest Ecology and Biogeosciences, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA 4 ESS – Watershed Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 5 Sierra Nevada Research Institute, University of California at Merced, Merced, CA, USA Abstract: The spatial distribution of snow water equivalent (SWE) is a key variable in many regional-scale land surface models. Currently, the assimilation of point-scale snow sensor data into these models is commonly performed without consideration of the spatial representativeness of the point data with respect to the model grid-scale SWE. To improve the understanding of the relationship between point-scale snow measurements and surrounding areas, we characterized the spatial distribution of snow depth and SWE within 1-, 4- and 16-km2 grids surrounding 15 snow stations (snowpack telemetry and California snow sensors) in California, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho and Oregon during the 2008 and 2009 snow seasons. More than 30 000 field observations of snowpack properties were used with binary regression tree models to relate SWE at the sensor site to the surrounding area SWE to evaluate the sensor representativeness of larger-scale conditions. -

PEAK to PRAIRIE: BOTANICAL LANDSCAPES of the PIKES PEAK REGION Tass Kelso Dept of Biology Colorado College 2012

!"#$%&'%!(#)()"*%+'&#,)-#.%.#,/0-#!"0%'1%&2"%!)$"0% !"#$%("3)',% &455%$6758% /69:%8;%+<878=>% -878?4@8%-8776=6% ABCA% Kelso-Peak to Prairie Biodiversity and Place: Landscape’s Coat of Many Colors Mountain peaks often capture our imaginations, spark our instincts to explore and conquer, or heighten our artistic senses. Mt. Olympus, mythological home of the Greek gods, Yosemite’s Half Dome, the ever-classic Matterhorn, Alaska’s Denali, and Colorado’s Pikes Peak all share the quality of compelling attraction that a charismatic alpine profile evokes. At the base of our peak along the confluence of two small, nondescript streams, Native Americans gathered thousands of years ago. Explorers, immigrants, city-visionaries and fortune-seekers arrived successively, all shaping in turn the region and communities that today spread from the flanks of Pikes Peak. From any vantage point along the Interstate 25 corridor, the Colorado plains, or the Arkansas River Valley escarpments, Pikes Peak looms as the dominant feature of a diverse “bioregion”, a geographical area with a distinct flora and fauna, that stretches from alpine tundra to desert grasslands. “Biodiversity” is shorthand for biological diversity: a term covering a broad array of contexts from the genetics of individual organisms to ecosystem interactions. The news tells us daily of ongoing threats from the loss of biodiversity on global and regional levels as humans extend their influence across the face of the earth and into its sustaining processes. On a regional level, biologists look for measures of biodiversity, celebrate when they find sites where those measures are high and mourn when they diminish; conservation organizations and in some cases, legal statutes, try to protect biodiversity, and communities often struggle to balance human needs for social infrastructure with desirable elements of the natural landscape. -

Spanish Peaks Wilderness

Mt. Bierstadt Field Trip Trip date: 6/17/2006 Ralph Swain, USFS R2 Wilderness Program Manager Observations: 1). The parking lot was nearly full (approximately 35 + vehicles) at 8:00 am on a Saturday morning. I observed better-than-average compliance with the dog on leash regulation. Perhaps this was due to my Forest Service truck being at the entrance to the parking lot and the two green Forest Service trucks (Dan and Tom) in the lot! 2). District Ranger Dan Lovato informed us of the District’s intent to only allow 40 vehicles in the lower parking lot. Additional vehicles will have to drive to the upper parking lot. This was new information for me and I’m currently checking in with Steve Priest of the South Platte Ranger District to learn more about the parking situation at Mt. Bierstadt. 3). I observed users of all types and abilities hiking the 14er. Some runners, 14 parties with dogs (of which 10 were in compliance with the dog-leash regulation), and a new- born baby being carried to the top by mom and dad (that’s a first for me)! Management Issues: 1). Capacity issue: I counted 107 people on the hike, including our group of 14 people. The main issue for Mt. Bierstadt, being a 14er hike in a congressionally designated wilderness, is a social issue of how many people are appropriate? Thinking back to Dr. Cordell’s opening Forum discuss on demographic trends and the growth coming to the west, including front-range Denver, the use on Mt. -

Rocky Mountain U.S

National Park Service Rocky Mountain U.S. Department of the Interior Rocky Mountain National Park Wild Basin Area Summer Trail Guide Welcome to Wild Basin. Rich in wildlife and scenery, this deep valley has flowing rivers, roaring waterfalls, and sparkling lakes rimmed by remote, jagged peaks. Tips for a Narrow Road, Limited Parking Watch the Weather: It Changes Quickly! Great Hike Wild Basin Road is gravel and often narrows to Thunderstorms are common in summer and one lane. It isn’t suitable for large vehicles like are dangerous. Plan your day to be below RVs. Park only in designated areas. Don’t park treeline by early afternoon. If you see building in wide spots in the road, which let oncoming storm clouds, head back to the trailhead. If cars pass each other. Violators may be ticketed caught in a lightning storm, get below treeline. or towed. Always carry storm gear, even if the sky is clear You Must Properly Store Food Items at when you start your hike. Trailheads and Wilderness Campsites Improperly stored food items attract wildlife, It might be summer, but expect snow, gusty including black bears, which can visit any time winds, and cold temperatures at any time. of day. Food items are food, drinks, toiletries, Carry layers of windproof clothing. If the cosmetics, pet food and bowls, and odiferous weather turns, you’ll be glad to have them. attractants. Garbage, including empty cans and food wrappers, must be stored or put in Bring the Right Gear trash or recycling bins. 3 Bring waterproof outer layers and extra lay- ers for warmth. -

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist Rank Mountain Peak Mountain Range Elevation Date Climbed 1 Mount Elbert Sawatch Range 14,440 ft 2 Mount Massive Sawatch Range 14,428 ft 3 Mount Harvard Sawatch Range 14,421 ft 4 Blanca Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,351 ft 5 La Plata Peak Sawatch Range 14,343 ft 6 Uncompahgre Peak San Juan Mountains 14,321 ft 7 Crestone Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,300 ft 8 Mount Lincoln Mosquito Range 14,293 ft 9 Castle Peak Elk Mountains 14,279 ft 10 Grays Peak Front Range 14,278 ft 11 Mount Antero Sawatch Range 14,276 ft 12 Torreys Peak Front Range 14,275 ft 13 Quandary Peak Mosquito Range 14,271 ft 14 Mount Evans Front Range 14,271 ft 15 Longs Peak Front Range 14,259 ft 16 Mount Wilson San Miguel Mountains 14,252 ft 17 Mount Shavano Sawatch Range 14,231 ft 18 Mount Princeton Sawatch Range 14,204 ft 19 Mount Belford Sawatch Range 14,203 ft 20 Crestone Needle Sangre de Cristo Range 14,203 ft 21 Mount Yale Sawatch Range 14,200 ft 22 Mount Bross Mosquito Range 14,178 ft 23 Kit Carson Mountain Sangre de Cristo Range 14,171 ft 24 Maroon Peak Elk Mountains 14,163 ft 25 Tabeguache Peak Sawatch Range 14,162 ft 26 Mount Oxford Collegiate Peaks 14,160 ft 27 Mount Sneffels Sneffels Range 14,158 ft 28 Mount Democrat Mosquito Range 14,155 ft 29 Capitol Peak Elk Mountains 14,137 ft 30 Pikes Peak Front Range 14,115 ft 31 Snowmass Mountain Elk Mountains 14,099 ft 32 Windom Peak Needle Mountains 14,093 ft 33 Mount Eolus San Juan Mountains 14,090 ft 34 Challenger Point Sangre de Cristo Range 14,087 ft 35 Mount Columbia Sawatch Range -

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geochronology Database for Central Colorado By T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt, 2009, Geochronology database for central Colorado: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 489, 13 p. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1 -

COLORADO CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL COALITION VISIT COLORADO! Day & Overnight Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail

CONTINENTAL DIVIDE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL DAY & OVERNIGHT HIKES: COLORADO CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL COALITION VISIT COLORADO! Day & Overnight Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail THE CENTENNIAL STATE The Colorado Rockies are the quintessential CDT experience! The CDT traverses 800 miles of these majestic and challenging peaks dotted with abandoned homesteads and ghost towns, and crosses the ancestral lands of the Ute, Eastern Shoshone, and Cheyenne peoples. The CDT winds through some of Colorado’s most incredible landscapes: the spectacular alpine tundra of the South San Juan, Weminuche, and La Garita Wildernesses where the CDT remains at or above 11,000 feet for nearly 70 miles; remnants of the late 1800’s ghost town of Hancock that served the Alpine Tunnel; the awe-inspiring Collegiate Peaks near Leadville, the highest incorporated city in America; geologic oddities like The Window, Knife Edge, and Devil’s Thumb; the towering 14,270 foot Grays Peak – the highest point on the CDT; Rocky Mountain National Park with its rugged snow-capped skyline; the remote Never Summer Wilderness; and the broad valleys and numerous glacial lakes and cirques of the Mount Zirkel Wilderness. You might also encounter moose, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, marmots, and pika on the CDT in Colorado. In this guide, you’ll find Colorado’s best day and overnight hikes on the CDT, organized south to north. ELEVATION: The average elevation of the CDT in Colorado is 10,978 ft, and all of the hikes listed in this guide begin at elevations above 8,000 ft. Remember to bring plenty of water, sun protection, and extra food, and know that a hike at elevation will likely be more challenging than the same distance hike at sea level. -

2011, Winter – Bikepacking the CT

News from the Colorado Trail Foundation WINTER 2011 Bikepacking (and Hike-A-Biking) the Colorado Trail By Judd Rohwer (Rohwer, of Sandia Park, New Mexico, is a member of that’s NUTS. Back of the Pack Racing, a team of riders that describes But then the wheels started turning. And I’m not itself as “a fundamental movement that supports the talking about the 29 inchers on my Black Sheep single- theory of ‘me against mainstream.’ Our team attempts speed. I started thinking about the adventure, the to do everything the ‘right way,’ but not your way. We glory ... and the risks. I started thinking about the are a group of engineers, pilots, dreamers and UFO mental preparation, the physical training, the gear ... chasers. One thing is certain. If the race is long enough, and the danger. we will catch you – maybe.” What follows is his The challenge of The Colorado Trail seemed so description of his bikepacking adventures last summer massive compared to the usual 24-hour mountain on The Colorado Trail.) bike races that we train and live for at Back of the Pack Racing. But I wanted to face the challenge head on, so I made a commitment to myself and started planning for a 2011 attempt at the CTR. Then reality hit: the reality of a 500-mile self- supported race hit me straight in the face. Racing myself to the edge of exhaustion and beyond didn’t sound like much fun. So, I quickly convinced myself that the best way to experience the CT was to approach the adventure as a self-supported tour, not a race. -

Primitive Areas Gore Range-Eagles Nest And

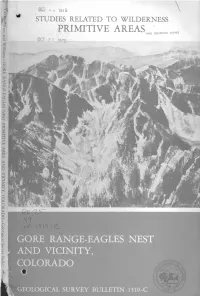

OC1 LO STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS PRIMITIVE AREAS OHIO GEOLOGICAL SURVEt OCT 2 r iQ70 GORE RANGE-EAGLES NEST AND VICINITY, COLORADO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1319-C f* MINERAL RESOURCES of the GORE RANGE-EAGLES NEST PRIMITIVE AREA and VICINITY, COLORADO Crest of Gore Range and head of middle fork of Black Creek. View is westward. Mount Powell (alt 13,534 ft) is massive peak at right of cen ter. Eagles Nest Mountain is at far right. Duck Lake is in right foreground. Trough above right end of lake marks fault zone of north-northwest trend. Dark area on steep front of rock glacier at left in photograph is typical "wet front" suggesting ice core in rock glacier. Mineral Resources of the Gore Range-Eagles Nest Primitive Area and Vicinity, Summit and Eagle Counties, Colorado By OGDEN TWETO and BRUCE BRYANT, U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, and by FRANK E. WILLIAMS, U.S. BUREAU OF MINES c STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS PRIMITIVE AREAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1319-C An evaluation of the mineral potential of the area UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. WASHINGTON : 1970 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 78-607129 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 ^. STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS PRIMITIVE AREAS The Wilderness Act (Public Law 88-577, Sept. 3, 1964) and the Conference Report on Senate bill 4, 88th Congress, direct the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines to make mineral surveys of wilderness and primitive areas. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County