Alcoholic Liver Disease: a Current Molecular and Clinical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sudan University of Science and Technology College of Graduate

Sudan University of Science and Technology College of Graduate Studies Detection of CDX2 Tumor Marker and Human Papilloma Virus in Esophageal Tumors اﻟﻜﺸﻒ ﻋﻦ اﻟﻮاﺳﻤﺔ اﻟﻮرﻣﯿﺔ CDX2 و ﻓﯿﺮوس اﻟﻮرم اﻟﺤﻠﯿﻤﻲ اﻟﺒﺸﺮي ﻓﻰ اورام اﻟﻤﺮيء A dissertation submitted for partial fulfillment for the requirement for M.Sc degree in Medical laboratory Science (Histopathology and cytology) Submitted by: Eslam Mohamed khoghali Ahmed B.SC (honors) in chemical pathology and histopathology – National Ribat University (2010) Supervised by: Dr. Mohammed Siddig Abdelaziz 2014 ﻗﺎل ﷲ ﺗﻌﺎﻟﻰ ۖ◌ ٰ◌ ﺻدق ﷲ اﻟﻌظﯾم ﺳورة اﻟﺗوﺑﺔ اﻵﯾﺔ 105 Dedication To my father…. My mother…. My brothers…. My friends… Eslam, 2014 Acknowledgement All great thanks are firstly to Allah. I would like to send thanks to my supervisor Dr. Mohamed Siddige Abdalaziz for his guidance and continuous assistance. Thanks are also extend to staff of histopathology and cytology in Ibn-Seina hospital and to members of histopathology and cytology department in Sudan University for science and technology for providing me materials and equipment, finally thanks to every one helped me. Eslam, 2014 Abstract This is a descriptive retrospective study conducted at Ibn Seina hospital and Sudan University of Science and Technology during the period from April 2014 to October 2014. The study aimed at detecting CDX2 and association of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) in esophageal tumor among Sudanese patients using immune-histochemistry and polymerase chain reaction. Samples from 30 patients previously diagnosed with esophageal tumor (20 with esophageal cancer and 10 with benign). Their ages ranging between 8 to 82 years with mean age 37. From each block two slides were cut one for CDX2 and other for HPV detection, also 10µ was cut from each block in eppendorf tube for detection of HPV type 18 gene using PCR.SPSS version 16 computer program was used to analyze the data. -

Health-Related Effects of Genetic Variations Of

FOCUS ON SPECIAL POPULATIONS HEALTH-RELATED EFFECTS OF GENETIC effects deter people from alcohol consumption and therefore VARIATIONS OF ALCOHOL-METABOLIZING have a protective effect against alcoholism. ENZYMES IN AFRICAN AMERICANS Because alcohol metabolism can significantly influence drinking behavior and the risk for alcoholism (Yin and Agarwal 2001), it is important to understand how genetic Denise M. Scott, Ph.D., and Robert E. Taylor, factors influence metabolism. The different ADH and M.D., Ph.D. ALDH isoforms are encoded by different genes, each of which again may be present in different variations (i.e., Alcohol metabolism involves two key enzymes—alcohol alleles). The occurrence of alternate alleles in a population dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase is termed polymorphism. The activity and distribution of (ALDH). There are several types of ADH and ALDH, each of the ADH and ALDH alleles and of the proteins they encode which may exist in several variants (i.e., isoforms) that have been intensively studied. For example, researchers differ in their ability to break down alcohol and its toxic have identified differences across ethnic groups in the fre metabolite acetaldehyde. The isoforms are encoded by quencies with which individual genes or gene variants different gene variants (i.e., alleles) whose distribution occur (Osier et al. 2002; Chou et al. 1999). This brief among ethnic groups differs. One variant of ADH is article examines the prevalence and effects of genetic vari ADH1B, which is encoded by several alleles. An allele ants of ADH and ALDH genes in African Americans. called ADH1B*3 is unique to people of African descent and certain Native American tribes. -

Biochemical and Physiological Research on the Disposition and Fate of Ethanol in the Body

Garriott's Medicolegal Aspects of Alcohol, 5th edition, Edited by James Garriott PhD Lawyers & Judges Publishing Co., Tuscon, AZ, 2008 Chapter 3 Biochemical and Physiological Research on the Disposition and Fate of Ethanol in the Body A.W. Jones, Ph.D., D.Sc. Synopsis . Repetitive F Drinking 3.1 Introduction G. Effect of Age on Widmark Parameters 3.2 Fate of Drugs in the Body H. Blood-Alcohol Profiles after Drinking Beer 3.3 Forensic Science Aspects of Alcohol I. Retrograde Extrapolation 3.4 Ethyl Alcohol J. Massive Ingestion of Alcohol under Real-World Conditions A. Chemistry K. Effects of Drugs on Metabolism of Ethanol . B Amounts of Alcohol Consumed L. Elimination Rates Ethanol in Alcoholics During Detoxification C. Alcoholic Beverages M. Ethanol Metabolism in Pathological States . D Analysis of Ethanol in Body Fluids N. Short-Term Fluctuations in Blood-Alcohol Profiles E. Reporting Blood Alcohol Concentration . Intravenous O vs. Oral Route of Ethanol Administration . F Water Content of Biofluids 3.8 Ethanol in Body Fluids and Tissues 3.5 Alcohol in the Body A. Water Content of Specimens A. Endogenous Ethanol . Urine B . B Absorption 1. Diuresis 1. Uptake from the gut 2. Urine-blood ratios 2. Importance of gastric emptying 3. Concentration-time profiles 3. Inhalation of ethanol vapors C. Breath 4. Absorption through skin 1. Breath alcohol physiology 5. Concentration of ethanol in the beverage consumed 2. Blood-breath ratios C. Distribution 3. Concentration-time profiles 1. Arterial-venous differences . Saliva D 2. Plasma/blood and serum/blood ratios 1. Saliva production 3. Volume of distribution 2. -

Associations of Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol Flush Reaction with Leukocyte Telomere Length in Korean Adults

Nutrition Research and Practice 2017;11(4):334-339 ⓒ2017 The Korean Nutrition Society and the Korean Society of Community Nutrition http://e-nrp.org Associations of alcohol consumption and alcohol flush reaction with leukocyte telomere length in Korean adults Hyewon Wang, Hyungjo Kim and Inkyung Baik§ Department of Foods and Nutrition, College of Science and Technology, Kookmin University, 77, Jeongnung-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02707, Korea BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES: Telomere length is a useful biomarker for determining general aging status. Some studies have reported an association between alcohol consumption and telomere length in a general population; however, it is unclear whether the alcohol flush reaction, which is an alcohol-related trait predominantly due to acetaldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency, is associated with telomere length. This cross-sectional study aimed to evaluate the associations of alcohol consumption and alcohol flush reaction with leukocyte telomere length (LTL). SUBJECTS/METHODS: The study included 1,803 Korean adults. Participants provided blood specimens for LTL measurement assay and reported their alcohol drinking status and the presence of an alcohol flush reaction via a questionnaire-based interview. Relative LTL was determined by using a quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Statistical analysis used multiple linear regression models stratified by sex and age groups, and potential confounding factors were considered. RESULTS: Age-specific analyses showed that heavy alcohol consumption (> 30 g/day) was strongly associated with a reduced LTL in participants aged ≥ 65 years (P < 0.001) but not in younger participants. Similarly, the alcohol flush reaction was associated with a reduced LTL only in older participants who consumed > 15 g/day of alcohol (P < 0.01). -

ALDH2(E487K) Mutation Increases Protein Turnover and Promotes Murine Hepatocarcinogenesis

ALDH2(E487K) mutation increases protein turnover and promotes murine hepatocarcinogenesis Shengfang Jina,1, Jiang Chenb,c, Lizao Chend, Gavin Histena, Zhizhong Lind, Stefan Grossa, Jeffrey Hixona, Yue Chena, Charles Kunga, Yiwei Chend, Yufei Fub, Yuxuan Lud, Hui Linc, Xiujun Caic, Hua Yanga, Rob A. Cairnse, Marion Dorscha, Shinsan M. Sua, Scott Billera, Tak W. Make,1, and Yong Cangb,d,1 aAgios Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Cambridge, MA 02139; bLife Sciences Institute and Innovation Center for Cell Signaling Network, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310058, China; cDepartment of General Surgery, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310058, China; dOncology Business Unit and Innovation Center for Cell Signaling Network, WuXi AppTec Co., Ltd., Shanghai 200131, China; and eThe Campbell Family Institute for Breast Cancer Research, Ontario Cancer Institute, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada M5G 2C1 Contributed by Tak W. Mak, June 4, 2015 (sent for review March 13, 2015; reviewed by Jorge Moscat) Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) in the liver major organ of ethanol detoxification, the relationship between removes toxic aldehydes including acetaldehyde, an intermediate ALDH2*2 and the risk for liver cancer remains unclear (15, 16). of ethanol metabolism. Nearly 40% of East Asians inherit an ALDH2 is highly conserved in humans and mice (17, 18), and inactive ALDH2*2 variant, which has a lysine-for-glutamate sub- several mouse models with modified ALDH2 activities have been stitution at position 487 (E487K), and show a characteristic alcohol developed (19). The closest model to the human ALDH2*2 poly- flush reaction after drinking and a higher risk for gastrointestinal morphism is the Aldh2 knockout (KO) mouse, which expresses no Aldh2 cancers. -

Published Work A.W

Professor A.W. Jones Ph.D., D.Sc. 1 PUBLISHED WORK A.W. Jones, BSc, PhD, DSc. PhD Thesis entitled “Equilibrium Partition Studies of Alcohol in Biological Fluids”, University of Wales, Cardiff, UK, 1974, 230 pp. DSc Thesis; Summary and reprints of 117 articles dealing with “Methods of Analysis, Distribution and Metabolism in the Body and Biological Effects of Alcohol and Narcotics”, University of Wales, Cardiff, UK, 1993. Books and government reports Andréasson R, Jones AW. Alkohol och trafikbrott (Alcohol and traffic crimes), National Board of Forensic Medicine, Stockholm, 1999, pp 1-150. Jones AW, Drugs and driving in Sweden: A compilation of published work. National Board of Forensic Medicine, Division of Forensic Toxicology, Linköping, 2009, pp 1-120. Jones AW, Perspectives in Drug Discovery. National Board of Forensic Medicine, Division of Forensic Toxicology, 2010, pp 1-118. Jones AW, Kugelberg FC, Enstedt C, Lundquist P. Alkoholundersökningar för rättsligt bruk (Alcohol analysis for legal purposes), Swedish National Laboratory of Forensic Science, 2014, pp 1-114. Jones AW. Research work published by the National Laboratory of Forensic Toxicology 1956-2013. National Board of Forensic Medicine, Division of Forensic Toxicology, Linköping, 2014, pp 1-143. 1974 1. Jones TP, Jones AW, Williams PM. Some recent developments in breath alcohol analysis. The Police Surgeon 6;80-86, 1974. 1975 2. Wright BM, Jones TP, Jones AW. Breath-alcohol analysis and the blood/breath ratio. Med Sci Law 15;205-210, 1975. 3. Jones AW, Wright BM, Jones TP. A historical and experimental study of the breath/blood alcohol ratio, In; Proceedings 6th International Conference on Alcohol, Drugs and Traffic Safety, S. -

ASSESSMENT of ALCOHOLIC FLUSH REACTION in DIFFERENT PEOPLE WHO ARE REGULAR in ALCOHOL and MEASURES to REDUCE ALCOHOLIC FLUSH Dr

VOLUME-7, ISSUE-1, JANUARY-2018 • PRINT ISSN No 2277 - 8160 Original Research Paper Clinical Research ASSESSMENT OF ALCOHOLIC FLUSH REACTION IN DIFFERENT PEOPLE WHO ARE REGULAR IN ALCOHOL AND MEASURES TO REDUCE ALCOHOLIC FLUSH Dr. Kanamala Arun Sree Chaitanya Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences Chand Roby P. Pooja Sree Chaitanya Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences P. Bhavana Sree Chaitanya Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences Kaitha. Sankarsh Sree Chaitanya Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences Reddy ABSTRACT Alcoholic ush syndrome is a condition in which the individuals develop ushes or blotches associated with erythema on face, neck, shoulders etc. This reaction is a result of accumulation of acetaldehyde, a metabolic byproduct of catabolic metabolism of alcohol. Materials and methods, Study method: This was a prospective observational study conducted for 14 months (June 2016-August 2017) in three tertiary care hospitals. Study site: The study was conducted in three tertiary care hospitals (of which one was 500 bedded and two were 300 bedded) and few rural areas. Study procedure: The study was done by collecting information from patient case sheets, from the patients and the patient care givers, based on the data a questionnaire is prepared. Nearly data of 702 chronic alcoholics was taken into consideration, of which only 639 people cooperated and provided the information. Study duration: The study was conducted for fourteen months (June 2016 – August2017) Results: The data of 639 people was collected who were chronic alcoholics of which males were 421 and females were 218 and the most effected age group was found to be 25-35years. They were having the complaints of headache, nausea, vomiting, erythema of face and general physical discomfort. -

In Silico Systems Analysis of Biopathways

In Silico Systems Analysis of Biopathways Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften der Universität Bielefeld. Vorgelegt von Ming Chen Bielefeld, im März 2004 MSc. Ming Chen AG Bioinformatik und Medizinische Informatik Technische Fakultät Universität Bielefeld Email: [email protected] Genehmigte Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Naturwissenschaften (Dr.rer.nat.) Von Ming Chen am 18 März 2004 Der Technischen Fakultät an der Universität Bielefeld vorgelegt Am 10 August 2004 verteidigt und genehmiget Prüfungsausschuß: Prof. Dr. Ralf Hofestädt, Universität Bielefeld Prof. Dr. Thomas Dandekar, Universität Würzburg Prof. Dr. Robert Giegerich, Universität Bielefeld PD Dr. Klaus Prank, Universität Bielefeld Dr. Dieter Lorenz / Dr. Dirk Evers, Universität Bielefeld ii Abstract In the past decade with the advent of high-throughput technologies, biology has migrated from a descriptive science to a predictive one. A vast amount of information on the metabolism have been produced; a number of specific genetic/metabolic databases and computational systems have been developed, which makes it possible for biologists to perform in silico analysis of metabolism. With experimental data from laboratory, biologists wish to systematically conduct their analysis with an easy-to-use computational system. One major task is to implement molecular information systems that will allow to integrate different molecular database systems, and to design analysis tools (e.g. simulators of complex metabolic reactions). Three key problems are involved: 1) Modeling and simulation of biological processes; 2) Reconstruction of metabolic pathways, leading to predictions about the integrated function of the network; and 3) Comparison of metabolism, providing an important way to reveal the functional relationship between a set of metabolic pathways. -

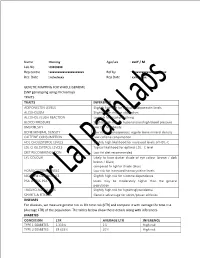

Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Rec. Date Rep Date GENE

Name : Dummy Age/sex : xxxY / M Lab No : 00000000 Rep centre : xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Ref by : xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Rec. Date : xx/xx/xxxx Rep Date : xx/xx/xxxx GENETIC MAPPING FOR WHOLE GENOME (SNP genotyping using microarray) TRAITS TRAITS INFERENCE ADIPONECTIN LEVELS Slightly high risk for reduced adiponectin levels ALCOHOLISM Slightly high risk for alcoholism ALCOHOL FLUSH REACTION Low risk for alcohol flushing BLOOD PRESSURE Slightly high risk for hypertension/high blood pressure BMI/OBESITY Low risk for obesity BONE MINERAL DENSITY Low risk for osteoporosis; regular bone mineral density CAFFEINE CONSUMPTION Low caffeine consumption HDL CHOLESTEROL LEVELS Slightly high likelihood for increased levels of HDL-C LDL CHOLESTEROL LEVELS Typical likelihood for optimal LDL -C level DIET RECOMMENDATION Low fat diet recommended EYE COLOUR Likely to have darker shade of eye colour (brown / dark brown / black) compared to lighter shade (blue) HOMOCYSTEINE LEVELS Low risk for increased homocysteine levels NICOTINE DEPENDENCE Slightly high risk for nicotine dependence PSA LEVELS PSA levels may be moderately higher than the general population TRIGLYCERIDE LEVELS Slightly high risk for hypertriglyceridemia SPORTS & FITNESS Genetic advantage for sprint/power athletics DISEASES For diseases, we measure genetic risk as life time risk (LTR) and compare it with average life time risk (Average LTR) of the population. The tables below show these details along with inferences. DIABETES CONDITION LTR AVERAGE LTR INFERENCE TYPE 1 DIABETES 1.333% 1% High -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2012/0022122 A1 Tokunaga (43) Pub

US 20120022122A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2012/0022122 A1 Tokunaga (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 26, 2012 (54) TREATMENT AND PREVENTION OF Publication Classification DELETERIOUS EFFECTS ASSOCATED (51) Int. Cl. WITH ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION A6II 3/426 (2006.01) A6IP 25/32 (2006.01) (76) Inventor: Richard Tokunaga, Honolulu, HI (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................................ 514/370 (US) (57) ABSTRACT The present invention provides to methods and compositions (21) Appl. No.: 13/248,375 that treat or prevent deleterious effects associated with alco hol consumption including alcohol-induced flush reaction and hangover. The methods and compositions include famo (22) Filed: Sep. 29, 2011 tidine and optionally succinic acid. The present invention further demonstrates compositions that include famotidine Related U.S. Application Data are effective at treating symptoms associated with a flush reaction in Subjects that are not significantly responsive to (62) Division of application No. 12/323,098, filed on Nov. treatments with the H1 antagonist loratidine or the H2 antago 25, 2008, now Pat. No. 8,058,296. nist cimetidine. Patent Application Publication Jan. 26, 2012 Sheet 1 of 2 US 2012/0022122 A1 FIG. 1 F.G. 2 Patent Application Publication Jan. 26, 2012 Sheet 2 of 2 US 2012/0022122 A1 FIG. 3A FIG. 3B US 2012/0022122 A1 Jan. 26, 2012 TREATMENT AND PREVENTION OF contributes to hangover, which is often felt by many the DELETERIOUS EFFECTS ASSOCIATED morning after alcohol consumption. Common hangover WITH ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION effects include headache, nausea, dizziness, fatigue, thirst, tension, anxiety, paleness, tremorand perspiration. It is com CROSS REFERENCE TO RELATED monly believed that black coffee or further consumption of APPLICATIONS alcohol in the morning reduces the symptoms; however, the effectiveness varies across individuals. -

Regional Variations in Helicobacter Pylori Infection

Regional variations in Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric atrophy and gastric cancer risk: The ENIGMA study in Chile Rolando Herrero, Katy Heise, Johanna Acevedo, Paz Cook, Claudia Gonzalez, Jocelyne Gahona, Raimundo Cortés, Luis Collado, María Enriqueta Beltrán, Marcos Cikutovic, et al. To cite this version: Rolando Herrero, Katy Heise, Johanna Acevedo, Paz Cook, Claudia Gonzalez, et al.. Regional variations in Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric atrophy and gastric cancer risk: The ENIGMA study in Chile. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2020, 15 (9), pp.e0237515. 10.1371/jour- nal.pone.0237515. inserm-02996939 HAL Id: inserm-02996939 https://www.hal.inserm.fr/inserm-02996939 Submitted on 9 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Regional variations in Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric atrophy and gastric cancer risk: The ENIGMA study in Chile 1,2 3 4 5,6 7 Rolando HerreroID *, Katy Heise , Johanna Acevedo , Paz Cook , Claudia GonzalezID , 8 8 9 3 Jocelyne Gahona , Raimundo CorteÂs , Luis -

Theme 10. Forensic-Medical Toxicology

Forensic medicine. Part 2. Forensic-medical examination of injuries caused by action of factors of the external environment. Forensic-medical examination of the material evidences Theme 10. Forensic-medical toxicology Guidelines for students and interns Судова медицина. Розділ 2. Судово-медична експертиза ушкоджень внаслідок дії факторів зовнішнього середовища. Судово-медична експертиза речових доказів Тема 10. Судово-медична токсикологія Методичні вказівки для студентів та лікарів інтернів МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОХОРОНИ ЗДОРОВ’Я УКРАЇНИ Харківський національний медичний університет Forensic medicine. Part 2. Forensic-medical examination of injuries caused by action of factors of the external environment. Forensic-medical examination of the material evidences Theme 10. Forensic-medical toxicology Guidelines for students and interns Судова медицина. Розділ 2. Судово-медична експертиза ушкоджень внаслідок дії факторів зовнішнього середовища. Судово-медична експертиза речових доказів Тема 10. Судово-медична токсикологія Методичні вказівки для студентів та лікарів інтернів Затверджено вченою радою ХНМУ. Протокол № 9 від 17.10.2019. Харків ХНМУ 2019 1 Forensic medicine. Part 2. Forensic-medical examination of injuries caused by action of factors of the external environment. Forensic-medical examination of the material evidences. Theme 10. Forensic Medical Toxicology: guidelines for students and interns / comp. Vasil Olhovsky, Mykola Gubin, Petr Kaplunovsky et al. – Kharkiv : KNMU, 2019. – 20 p. Compilers Vasil Olkhovsky Mykola Gubin Petr Kaplunovsky Vjacheslav Sokol Vladyslav Bondarenko Pavlo Leontiev Edgar Grygorian Nataliia Konoval Судова медицина. Розділ 2. Судово-медична експертиза ушкоджень внаслідок дії факторів зовнішнього середовища. Судово-медична експертиза речових доказів. Тема 10. Судово-медична токсикологія: методичні вказівки для студентів та лікарів інтернів / упоряд. В. О. Ольховський, М. В. Губін, П. А. Каплуновський та ін.