Cora Wilding and the Sunlight League

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anna Kavan Meets Frank Sargeson on a Special

1 NGAIO MARSH, 23 April 1895—18 February 1982 Bruce Harding Dame Ngaio Marsh, the detective novelist, dramatist, short-story writer, theatre producer, non-fiction writer, scriptwriter, autobiographer, painter and critic was born in Christchurch, New Zealand on 23 April 1895. Her birth in the closing years of Queen Victoria’s reign and her childhood and adolescence in the twilight—albeit a transferred one—of the Edwardian era were to prove crucial in shaping the prevailing temper and tone of her outlook, particularly when Marsh set out to experiment with writing as a young woman. Her very name enacts a symbolic and liminal binary opposition between Old and New World elements: a confluence echoing the indigenous (the ngaio being a native New Zealand coastal tree) and the imported (a family surname from the coastal marshes of Kent, England). Seen thus, “Ngaio” connotes New World zest—a freshness of outlook, insight and titanic energy—while “Marsh” suggests an Old World gravitas grounded in notions of a stable, class-based lineage and secure traditions. The tension between these twin imperatives and hemispheres drove and energized Marsh’s career and life-pattern (of ongoing dualities: New Zealand-England; writing-production) and enabled her to live what Howard McNaughton has called an incognito/”alibi career” in a pre-jet age of sailing boats and vast distances and time horizons between her competing homelands (in Lidgard and Acheson, pp.94-100). Edith Ngaio Marsh’s Taurian date of birth was both richly symbolic and portentous, given that 23 April is both St George’s Day and the legendary birthdate of Marsh’s beloved Bard, Shakespeare. -

Scientists' Houses in Canberra 1950–1970

EXPERIMENTS IN MODERN LIVING SCIENTISTS’ HOUSES IN CANBERRA 1950–1970 EXPERIMENTS IN MODERN LIVING SCIENTISTS’ HOUSES IN CANBERRA 1950–1970 MILTON CAMERON Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cameron, Milton. Title: Experiments in modern living : scientists’ houses in Canberra, 1950 - 1970 / Milton Cameron. ISBN: 9781921862694 (pbk.) 9781921862700 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Scientists--Homes and haunts--Australian Capital Territority--Canberra. Architecture, Modern Architecture--Australian Capital Territority--Canberra. Canberra (A.C.T.)--Buildings, structures, etc Dewey Number: 720.99471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Sarah Evans. Front cover photograph of Fenner House by Ben Wrigley, 2012. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press; revised August 2012 Contents Acknowledgments . vii Illustrations . xi Abbreviations . xv Introduction: Domestic Voyeurism . 1 1. Age of the Masters: Establishing a scientific and intellectual community in Canberra, 1946–1968 . 7 2 . Paradigm Shift: Boyd and the Fenner House . 43 3 . Promoting the New Paradigm: Seidler and the Zwar House . 77 4 . Form Follows Formula: Grounds, Boyd and the Philip House . 101 5 . Where Science Meets Art: Bischoff and the Gascoigne House . 131 6 . The Origins of Form: Grounds, Bischoff and the Frankel House . 161 Afterword: Before and After Science . -

Family Experiments Middle-Class, Professional Families in Australia and New Zealand C

Family Experiments Middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c. 1880–1920 Family Experiments Middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c. 1880–1920 SHELLEY RICHARDSON Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Richardson, Shelley, author. Title: Family experiments : middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c 1880–1920 / Shelley Richardson. ISBN: 9781760460587 (paperback) 9781760460594 (ebook) Series: ANU lives series in biography. Subjects: Middle class families--Australia--Biography. Middle class families--New Zealand--Biography. Immigrant families--Australia--Biography. Immigrant families--New Zealand--Biography. Dewey Number: 306.85092 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. The ANU.Lives Series in Biography is an initiative of the National Centre of Biography at The Australian National University, ncb.anu.edu.au. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Photograph adapted from: flic.kr/p/fkMKbm by Blue Mountains Local Studies. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents List of Illustrations . vii List of Abbreviations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Introduction . 1 Section One: Departures 1 . The Family and Mid-Victorian Idealism . 39 2 . The Family and Mid-Victorian Realities . 67 Section Two: Arrival and Establishment 3 . The Academic Evangelists . 93 4 . The Lawyers . 143 Section Three: Marriage and Aspirations: Colonial Families 5 . -

13 1 a R T + O B Je C T 20 18

NEW A RT + O B J E C T COLLECTORS ART + OBJECT 131 ART 2018 TWENTIETH CENTURY DESIGN & STUDIO CERAMICS 24 –25 JULY AO1281FA Cat 131 cover.indd 1 10/07/18 3:01 PM 1 THE LES AND AUCTION MILLY PARIS HIGHLIGHTS COLLECTION 28 JUNE PART 2 Part II of the Paris Collection realised a sale The record price for a Tony Fomison was total of $2 000 000 and witnessed high also bettered by nearly $200 000 when clearance rates and close to 100% sales by Ah South Island, Your Music Remembers value, with strength displayed throughout Me made $321 000 hammer ($385 585) the lower, mid and top end of the market. against an estimate of $180 000 – The previous record price for a Philip $250 000. Illustrated above left: Clairmont was more than quadrupled Tony Fomison Ah South Island, Your Music when his magnificent Scarred Couch II Remembers Me was hammered down for $276 000 oil on hessian laid onto board ($331 530) against an estimate of 760 x 1200mm $160 000 – $240 000. A new record price realised for the artist at auction: $385 585 2 Colin McCahon Philip Clairmont A new record price Scarred Couch II realised for the artist North Shore Landscape at auction: oil on canvas, 1954 mixed media 563 x 462mm and collage on $331 530 unstretched jute Milan Mrkusich Price realised: $156 155 1755 x 2270mm Painting No. II (Trees) oil on board, 1959 857 x 596mm Price realised: $90 090 John Tole Gordon Walters Timber Mill near Rotorua Blue Centre oil on board PVA and acrylic on 445 x 535mm Ralph Hotere canvas, 1970 A new record price realised Black Window: Towards Aramoana 458 x 458mm for the artist at auction: acrylic on board in colonial sash Price realised: $73 270 $37 235 window frame 1130 x 915mm Price realised: $168 165 Peter Peryer A new record price realised Jam Rolls, Neenish Tarts, Doughnuts for the artist at auction: gelatin silver print, three parts, 1983 $21 620 255 x 380mm: each print 3 RARE BOOKS, 22 AUG MANUSCRIPTS, George O’Brien Otago Harbour from Waverley DOCUMENTS A large watercolour of Otago Harbour from Waverley. -

Download PDF Catalogue

THE 21ST CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE NEW COLLECTORS ART THE JIM DRUMMOND COLLECTION THE NEW ZEALAND SALE DECORATIVE ARTS THE 21ST CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE NEW COLLectors art wednesday 22 april 6.30pm THE JIM DRUMMOND COLLECTION saturday 2 may and sunday 3 may 10am please turn to subtitle page for detailed session times THE NEW ZEALAND SALE + DECORATIVE ARTS thursday 14 may 6.30pm RARE BOOKS IN CONJUNCTION WITH paM PLUMBLY a separate catalogue will be available thursday 14 may conditions of sale page 78 absentee bid form page 79 contacts page 80 buyer’s premium on all auctions in this catalogue 15% 3 Abbey Street, Telephone +64 9 354 4646 Newton Freephone 0800 80 60 01 PO Box 68 345, Facsimile +64 9 354 4645 Newton [email protected] Auckland 1145, www.artandobject.co.nz New Zealand entries invited TWENTIETH CENTURY DESIGN TH garth Chester Bob Roukema JUNE 11 2009 Curvesse Chair wing back Chair $3500 - $4000 $2000 - $3000 CONTEMPORARY Len Castle ART + Slab Sided Pot $1000 - $2000 OBJECTS TH Angela Singer MAY 28 2009 Untitled $1000 - $1500 each Peter Peryer IMPORTANT Trout vintage gelatin silver print, 1987 PHOTOGRAPHS $9000 - $14 000 MAY 28TH 2009 One giant leap. The all-new, technologically advanced Lexus RX350 has arrived. Why is the all-new RX350 such an excellent personification of forward thinking? Perhaps it’s the way it innovatively blends the styling of an SUV with the luxury you’ve come to expect from Lexus. With a newly enhanced 3.5 litre engine and Active Torque Control All-Wheel Drive, you’ll have outstanding power coupled with superb response and handling. -

Community Services Committee Agenda 6 November 2000

ROBERT MCDOUGALL ART GALLERY AND ART ANNEX REPORT ON ACTIVITIES FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 1 JULY 1999 - 30 JUNE 2000 PREPARED BY: ART GALLERY DIRECTOR AND ART GALLERY STAFF TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO. BUSINESS UNIT SUMMARY REPORT ART COLLECTION REPORT EXHIBITIONS REPORT INFORMATION & ADVICE REPORT ACQUISITION APPENDIX PAGE NO. 3 6 8 15 18 BUSINESS UNIT ART GALLERY FINANCIAL RESULTS FOR TWELVE MONTHS TO 30 JUNE 2000 Financial Performance Last Year Current Year Corporate Plan Reference Page 8.3.1 Actual Budget Actual Expenditure Art Collection $778,121 $755,678 $718,190 Exhibitions $1,218,120 $1,274,813 $1,131,178 Information & Advice $559,780 $659,545 $717,276 $2,556,021 $2,690,036 $2,566,644 Revenue Art Collection -$81,383 -$58,725 -$52,127 Exhibitions -$325,346 -$317,000 -$185,530 Information & Advice -$38,781 -$202,000 -$143,773 -$445,510 -$577,725 -$381,430 Net Cost of Art Gallery Operations $2,110,511 $2,112,311 $2,185,214 Capital Outputs Renewals & Replacements $28,764 $31,800 $35,753 Asset Improvements $0 $0 $0 New Assets $365,764 $179,887 $170,082 Sale of Assets -$22 $0 $0 Net Cost of Art Gallery Capital Programme $394,506 $211,687 $205,835 Objective To enhance the cultural well-being of the community through the cost effective provision and development of a public art museum, to maximise enjoyment of visual art exhibitions, and to promote public appreciation of Canterbury art, and more widely, the national cultural heritage by collecting, conserving, researching and disseminating knowledge about art. -

Toi Tangata | Arts Update

TOI TANGATA | ARTS UPDATE 04 October 2019 News Final chance to view and take home any of The Christchurch Press Archives that we currently have in storage. These cover the period from the 1950s through to 1971 and are Bound copies often covering three months in one volume. If you have any interest in viewing them and/or taking one or more home then please contact [email protected] to arrange a time to view. These will all be cleared from Locke by Friday OctoBer 11th UC Arts at the Arts Centre On Tuesday evening we held the OctoBer presentation of An Evening With, this month presented By Bradford P. Wilson. Bradford is a visiting academic from Princeton University, here as part of the Erskine programme. He will Be spending a couple of weeks at UC as a CanterBury Fellow. His talk on the life and times of Alexander Hamilton was very interesting, and was followed By thought-provoking questions. The event was opened by UC Consortia Chamber Choir, performing two songs from Hamilton: An American Musical. School of Music On Saturday night we were delighted to attend the UC Blues Awards! It was a stellar evening to celeBrate with all the winners, But in particular, it was fantastic to see Music and Arts nominees recognised for their hard work and dedication. Congratulations to our two students, Thomas Bedggood and Wenting Yang, who Both won awards! On Monday night, Head of New Music and Senior Lecturer, ReuBen de Lautour, presented ‘This is not a Piano’ for New Music Central. -

Lessons in Ephemera: Teaching and Learning Through Cultural Heritage Collections

Melissa McMullan and Joanna Cobley Lessons in Ephemera: Teaching and Learning through Cultural Heritage Collections This article synthesizes an intern’s experience assessing the University of Canterbury’s (UC) theatre and concert music program ephemera collec- tion for its teaching and research potential, and evaluating its storage and preservation needs. Held at the Macmillan Brown Library and Archive (MB), the collection comprises around 6,000 items and takes up seven linear meters of physical storage space. The ephemera functioned as a portal into the evolution of Christchurch’s theatrical and concert music history, giving weight to the collection as a rich local historical resource worthy of keeping. The ephemera reflected how British, European, and American cultural practices were infused into colonial Christchurch’s theatrical and concert music scene. The collection also revealed a tradi- tion of UC teachers who, since its establishment in 1873 as Canterbury College, actively shaped, participated in, and facilitated the develop- ment of Christchurch’s theatre and concert music heritage. Overall, the collection’s research value was its localism. Different ways of engaging researchers with the ephemera were considered, in addition to identify- ing the transferable skills the intern gained. With growing interest from students about internships, the authors also address questions about long-term impact and scalability of cultural-heritage collection-based in- tern and/or classroom-based learning projects more generally. Our main message for higher education management and those charged with the custodianship of cultural heritage collections is that hands-on learning helps students appreciate and value these locally significant collections. Academic archivists and librarians understand the value of working with cultural heritage collections, such as ephemera, yet the size and scope of these often uncata- logued, closed-storage collections can deter access.1 Connecting teaching staff and 1. -

Ryman Healthcare ANNUAL REPORT 2021 RYMAN HEALTHCARE

Ryman Healthcare ANNUAL REPORT 2021 RYMAN HEALTHCARE Cover image features Ryman residents Norris Aitken, Nola Cutting, Muriel Feasey, Eng Dick, Helen Aitken and Richard Fisher. ANNUAL REPORT 2021 Our mission remains the same as it has been for the past 37 years - the care we offer has to be “good enough for Mum or Dad”. RYMAN HEALTHCARE 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2021 4 Chair’s report 10 Stats and facts 12 Group chief executive’s report 20 Current villages under development 22 Future villages in our pipeline 26 Our directors 28 Our senior executives 31 Who we are and how we create value 39 What matters most to our stakeholders 43 Caring for our residents and our communities 55 Caring for our people 65 Caring for our environment 73 Providing a sustainable outcome for all stakeholders 77 Embracing innovation and technology 81 Our financials 139 Statement of corporate governance 156 Rymanians 162 Our village locations 164 Directory 3 RYMAN HEALTHCARE Chair’s report Ryman residents Norm Reid and Maggie Gubbins with chair, Dr David Kerr. 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2021 We bore the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic during the 2021 financial year. I am pleased to report that we have come through well and are in good shape for future growth. DR DAVID KERR CHAIR, RYMAN HEALTHCARE 5 RYMAN HEALTHCARE “We are enormously grateful for the extra effort our team has put in to keep everyone safe.” The board of Ryman A good result in a difficult year Healthcare is proud of what The pandemic has been a once-in-a-generation challenge, but has been achieved in the most we kept everyone safe. -

Download PDF Catalogue

Front and back covers: Shane Cotton, lots 31 – 34 ART + OBJECT Art+Object 3 Abbey Street Newton Auckland PO Box 68345 Wellesley Street Auckland 1141 Tel +64 9 354 4646 Free 0 800 80 60 01 Fax +64 9 354 4645 [email protected] www.artandobject.co.nz instagram: @artandobject facebook: Art+Object youtube: ArtandObject Photography: Sam Hartnett 24.09.19 Design: Fount–via Print: Graeme Brazier EXHIBITING QUALITY LANDSCAPES NEW ZEALAND'S FINEST LUXURY PROPERTIES PAIHIA ROAD BAY OF ISLANDS This significant Bay of Islands property comprises of a substantial home on approximately 2.62 hectares, with a predominant northerly aspect and an elevated outlook. The property’s location commands views from Opua through to Russell, Waitangi and beyond the Black Rocks to Mataka Station. Designed by the highly respected architect, Ron Sang, the home exhibits superior features and a quality build. Regard to the aspect and location is evident throughout. The unusual curved design ensures outstanding views from every room. luxuryrealestate.co.nz/NT149 445 MOONEY ROAD QUEENSTOWN An elevated, private and sunny 3.5 hectares with expansive views is the setting for this substantial family home of 457 square metres designed for easy living and entertaining. Six bedrooms including master with ensuite and walk in wardrobe, main bathroom with full bath, and guest room with private ensuite, two living rooms, a serious cooks kitchen with scullery, an office and three car garaging complete the contemporary floor-plan. Canadian cedar cladding outside and high quality walnut joinery inside give a sophisticated alpine feel. luxuryrealestate.co.nz/QN47 636 HUNTER ROAD QUEENSTOWN Located in the golden circle of country homes 58 Hunter Road is one of Queenstown's most secluded estates set in a very private and unique environment. -

Olivia Spencer Bower Retrospective 1977

759. 993 SPE FOOTNOTES (1) BlIlh CerllllCale venlled (2) The IWO sefles at Holton Ie MOOf Hall p<ilf'llangs 0lMa made on both 0CC3Sl00S 01 her return tnps 10 England are not SImply palntll'lgs at an 3rbllrary place they ale a pilgrimage of lamily identity - a lost hefllage. The cows,trees. horses, fields. poocls. msundial have an unpl'eceoellled exactness of placing Their presence IS as ~ In larnity tradilion - immovable 35 lamity gen ealogey yel1ranSIent and rnyslerlOUSas the homes must ha ....e been 10 her. intangible. Sometimes the sundial Olivia dePIcts in the Hall paintings 'opens' right out into the surrounding spaces. other limes is embraced by Banking yellows. as otller secluded and conceale<l. Halton Ie MOOr Hall made a Slgnihcant rnpression on 0lMa. The laler 1960's serIes nave a senSlllVlty unSIJ(' passed In most of O~vta's palll\JogS It seems as If the return to the place ot the hefltage thai rnlQhl have been hers fostered in her. some of her greater artistIC slreng1hs The IocKI colour and wide IOnaI Qua~ty 01 the watercoloufs suggest a deep sense of 1oca\JOfl related to symbolic content landscape here IS the diarist 01 IeeIing ow.a has preferred not 10 sell mosl 01 these pauliings (3) Amongst Olivia's coIIeclJoo of her mother's Slade Art SChool memotabilia are some analomicaJ tile draWIngs Rosa salvaged Irom a llIe drawing etass dust bm II was dOne by one ol the 'beller' students and in keeping with the criteria at the lime. works not el«:ellent in every way were deslfoyect. -

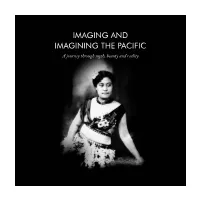

Imaging and Imagining the Pacific

IMAGING AND IMAGINING THE PACIFIC A journey through myth, beauty and reality First Published in November 2010 by the University of Canterbury Macmillan Brown Library and the School of Fine Arts in conjunction with the Macmillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies as part of the 75th Anniversary celebrations of John Macmillan Brown. ISBN: 978-0-9864670-1-1 Cover illustration: Samoan Woman c. 1880–1934, A J Tattersall (1861–1951), photograph IMAGING AND IMAGINING ‘I opened my eyes in a world no feature of which I could recognize. Everything around me was of the most dazzling beauty’ 1 John Macmillan Brown The Pacific Islands are in many respects naturally paradisiac; favoured as holiday 1. John Macmillan Brown. Published spots for their beautiful sandy beaches, enticingly crystal clear water and all-year- under the pseudonym Godfrey Sweven. Limanora; the island of progress. Putnam, round warm temperatures. Despite the relatively rapid settlement of Westerners New York, 1903, pp.1. in the Pacific, the transition from Western ethnocentric and anthropological viewpoints to understanding indigenous cultures has been slow. As a form of documentation, photography is often misleadingly perceived as truthful. Because photographic images are taken at a particular point in time and represent the real world it is easy to forget that the photographer has made crucial compositional and stylistic decisions. This exhibition explores a range of Western representations of the Pacific in the early twentieth century; from R.J.Baker’s romantic portraits charged with emotion to the sexualised and sensuous poses of A.J.Tattersall’s idyllic women. John Macmillan Brown’s photographs are distinct from the ones of professional photographers because of their inherent snapshot quality evoking the nostalgia of family albums.