An Artist's Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studio New Zealand Edition April 1948

i STUDIO-. , AND QUEENS- Founded in 1893 Vol 135 No &,I FROM HENRY VIII TO April 1948 -'- - RECENT IMPORTANT ' ARTICLES .. PAUL NASH 1889-1946 . Foreword by the Rt. Hon. ~gterFraser, C.H., P.C., M.P., (March) # ' - Prime Minister of New Zealand page IOI THE HERITAGE OF ART W INDl+, Contemporary Art in New Zealand by Roland Hipkins page Ioa by John Irwin I. 11 AND m New Zealand War Artists page 121 .. (~ecember,]anuary and February) - - Maori Art by W. J. Phillipps page 123 ' '-- I, JAMBS BAT- AU Architecture in New Zealand by Cedric Firth page 126 Book Production in New zealand page 130 - I, CITY OF BIRMINGW~~ ART GALLB&Y nb I by Trenchard Cox ..-- COLOUR PLA,"S . [Dctober) -7- SWSCVLPTwRB IN TEE HOME - WAXMANGUby Alice F. Whyte page 102 -- 1, -L by Kmeth Romney Towndrow -7 - STILL LIFE by T. A. McCormack page 103 (&ptember) ODE TO AUTUMN by A. Lois White page 106 NORWCH CASTLE MUSgUM -. AND ART GALLERY - PORTRAIT OF ARTIST'S WEB by M. T. Woollaston page 107 V. - by G. Barnard , ABSTRACT-SOFT'STONE WkTH WORN SHELL AND WOOD - L (August) - - by Eric Lee Johnson page I 17 1 -*, 8 I20 ~wyrightin works rernohcd in - HGURB COMPOSITION by Johtl Weeks page TH~snn,ro is stridty rewed ' 'L PATROL, VBUA LAVBLLA, I OCTOBER, 1943, by J. Bowkett Coe page 121 . m EDITOR is always glad to consfder proposals for SVBSCBIPTION Bdm (post free) 30s. Bound volume d be s&t to ,SmIO in edftorial contrlbutlons, but a letter out&& the (six issues) 17s 61 Caaads. -

Family Experiments Middle-Class, Professional Families in Australia and New Zealand C

Family Experiments Middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c. 1880–1920 Family Experiments Middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c. 1880–1920 SHELLEY RICHARDSON Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Richardson, Shelley, author. Title: Family experiments : middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c 1880–1920 / Shelley Richardson. ISBN: 9781760460587 (paperback) 9781760460594 (ebook) Series: ANU lives series in biography. Subjects: Middle class families--Australia--Biography. Middle class families--New Zealand--Biography. Immigrant families--Australia--Biography. Immigrant families--New Zealand--Biography. Dewey Number: 306.85092 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. The ANU.Lives Series in Biography is an initiative of the National Centre of Biography at The Australian National University, ncb.anu.edu.au. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Photograph adapted from: flic.kr/p/fkMKbm by Blue Mountains Local Studies. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents List of Illustrations . vii List of Abbreviations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Introduction . 1 Section One: Departures 1 . The Family and Mid-Victorian Idealism . 39 2 . The Family and Mid-Victorian Realities . 67 Section Two: Arrival and Establishment 3 . The Academic Evangelists . 93 4 . The Lawyers . 143 Section Three: Marriage and Aspirations: Colonial Families 5 . -

About People

All about people RYMAN HEALTHCARE ANNUAL REPORT 2019 We see it as a privilege to look after older people. RYMAN HEALTHCARE 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 04 Chair’s report 12 Chief executive’s report 18 Our directors 20 Our senior executives 23 How we create value over time 35 Enhancing the resident experience 47 Our people are our greatest resource 55 Serving our communities 65 The long-term opportunities are significant 75 We are in a strong financial position 123 We value strong corporate governance 3 RYMAN HEALTHCARE CHAIR’S REPORT We continue to create value 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 RYMAN HEALTHCARE CHAIR Dr David Kerr Ryman has been a care company since it started 35 years ago. As we continue to grow, we continue to create value for our residents and their families, our staff, and our shareholders by putting care at the heart of everything we do. We’re a company with a purpose – to look after older people. We know that if we get our care and resident experience right, and have happy staff, the financial results take care of themselves. I believe purpose and profitability are comfortable companions. Integrating the two supports us in creating value over time. This year, we continue to use the Integrated Reporting <IR> Framework* to share the wider story of how we create that value. *For more information on the <IR> Framework, visit integratedreporting.org 5 RYMAN HEALTHCARE “I believe purpose As a company we’re very focused on growth, but we will not compromise our core value of and profitability are putting our residents first. -

Mccahon House Invites You to Dinner

McCahon House invites you to dinner McCahon House hosts three Artists in Residence per year. As part of each residency a bespoke dinner between our current artist and a guest chef is created. Join us for an evening of art inspired cuisine, and be part of an ongoing dialogue where ideas around art are exchanged amongst artists and peers. These events are exclusive to the Gate Project. We Roasted carrot with kaffir lime sauce invite you to join and help strengthen opportunities and orange blossom candy floss by for New Zealand’s artists and our culture. For more chef Alex Davies of Gatherings, information about the Gate Project and to join visit: Christchurch, in collaboration with mccahonhouse.org.nz/gate 2019 artist in resident, Jess Johnson. — The Gate Project ART + OBJECT Tel +64 9 354 4646 Free 0 800 80 60 01 3 Abbey Street Fax +64 9 354 4645 Newton Auckland [email protected] www.artandobject.co.nz PO Box 68345 Wellesley Street instagram: @artandobject Auckland 1141 facebook: Art+Object youtube: ArtandObject Photography: Sam Hartnett Design: Fount–via Print: Graeme Brazier Th is auction event, including art works made solely by Colin Marti Friedlander Gretchen Albrecht underneath McCahon's "As there is a McCahon, felt like a fi tting tribute in 2019, his Centenary constant fl ow of light ..." year. We hoped to put together a small off ering that would Courtesy the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust refl ect the quality and variety of work that McCahon Marti Friedlander Archive, E.H. McCormick Research produced during his life-time and I think you will fi nd that Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, on loan from the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust, 2002 within these pages. -

13 1 a R T + O B Je C T 20 18

NEW A RT + O B J E C T COLLECTORS ART + OBJECT 131 ART 2018 TWENTIETH CENTURY DESIGN & STUDIO CERAMICS 24 –25 JULY AO1281FA Cat 131 cover.indd 1 10/07/18 3:01 PM 1 THE LES AND AUCTION MILLY PARIS HIGHLIGHTS COLLECTION 28 JUNE PART 2 Part II of the Paris Collection realised a sale The record price for a Tony Fomison was total of $2 000 000 and witnessed high also bettered by nearly $200 000 when clearance rates and close to 100% sales by Ah South Island, Your Music Remembers value, with strength displayed throughout Me made $321 000 hammer ($385 585) the lower, mid and top end of the market. against an estimate of $180 000 – The previous record price for a Philip $250 000. Illustrated above left: Clairmont was more than quadrupled Tony Fomison Ah South Island, Your Music when his magnificent Scarred Couch II Remembers Me was hammered down for $276 000 oil on hessian laid onto board ($331 530) against an estimate of 760 x 1200mm $160 000 – $240 000. A new record price realised for the artist at auction: $385 585 2 Colin McCahon Philip Clairmont A new record price Scarred Couch II realised for the artist North Shore Landscape at auction: oil on canvas, 1954 mixed media 563 x 462mm and collage on $331 530 unstretched jute Milan Mrkusich Price realised: $156 155 1755 x 2270mm Painting No. II (Trees) oil on board, 1959 857 x 596mm Price realised: $90 090 John Tole Gordon Walters Timber Mill near Rotorua Blue Centre oil on board PVA and acrylic on 445 x 535mm Ralph Hotere canvas, 1970 A new record price realised Black Window: Towards Aramoana 458 x 458mm for the artist at auction: acrylic on board in colonial sash Price realised: $73 270 $37 235 window frame 1130 x 915mm Price realised: $168 165 Peter Peryer A new record price realised Jam Rolls, Neenish Tarts, Doughnuts for the artist at auction: gelatin silver print, three parts, 1983 $21 620 255 x 380mm: each print 3 RARE BOOKS, 22 AUG MANUSCRIPTS, George O’Brien Otago Harbour from Waverley DOCUMENTS A large watercolour of Otago Harbour from Waverley. -

2016 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 INTRODUCTION Andre Brönnimann with two of the subjects of his winning portrait - Ria Wihapi Waikerepuru and Te Rawanake Robinson-Coles at the opening of the Adam Portraiture Award 2016. Treasurers, first John Sladden and then Richard 2016 was a year of Tuckey, to improve the quality of our budgets and endeavour, rewarded financial control. We are all very grateful for the commitment, the good humour and fellowship that over almost all of the full David brought to our affairs. Our fellow Trustee, Mike Curtis – a Partner with Deloitte – continued as range of our activities. It Chairman of the Finance and Planning Committee. presented us with a number In December we were pleased to be able to elect two new Trustees. Dr. David Galler, a well-known of challenges, ones of intensive care specialist in Auckland, and the personnel; of gallery space; author of a recent bestselling book about his life and work, Things That Matter. David brings his of governance; and, as wide knowledge of Auckland to our deliberations, along with a strong management background and always, of funding. a life-long interest in art. Helen Kedgley, who was Director of the Pātaka Art and Museum in Porirua But I would like to start by stating my own personal pleasure and satisfaction at the excellence of last year’s exhibition programme, a view that is shared, I know, by many of you. Quite apart from their intrinsic interest, and the pleasure as well as insight that they bring, these presentations are enhancing our reputation nationally and leading to increased cooperation with galleries and collectors both in this country and overseas. -

Community Services Committee Agenda 6 November 2000

ROBERT MCDOUGALL ART GALLERY AND ART ANNEX REPORT ON ACTIVITIES FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 1 JULY 1999 - 30 JUNE 2000 PREPARED BY: ART GALLERY DIRECTOR AND ART GALLERY STAFF TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO. BUSINESS UNIT SUMMARY REPORT ART COLLECTION REPORT EXHIBITIONS REPORT INFORMATION & ADVICE REPORT ACQUISITION APPENDIX PAGE NO. 3 6 8 15 18 BUSINESS UNIT ART GALLERY FINANCIAL RESULTS FOR TWELVE MONTHS TO 30 JUNE 2000 Financial Performance Last Year Current Year Corporate Plan Reference Page 8.3.1 Actual Budget Actual Expenditure Art Collection $778,121 $755,678 $718,190 Exhibitions $1,218,120 $1,274,813 $1,131,178 Information & Advice $559,780 $659,545 $717,276 $2,556,021 $2,690,036 $2,566,644 Revenue Art Collection -$81,383 -$58,725 -$52,127 Exhibitions -$325,346 -$317,000 -$185,530 Information & Advice -$38,781 -$202,000 -$143,773 -$445,510 -$577,725 -$381,430 Net Cost of Art Gallery Operations $2,110,511 $2,112,311 $2,185,214 Capital Outputs Renewals & Replacements $28,764 $31,800 $35,753 Asset Improvements $0 $0 $0 New Assets $365,764 $179,887 $170,082 Sale of Assets -$22 $0 $0 Net Cost of Art Gallery Capital Programme $394,506 $211,687 $205,835 Objective To enhance the cultural well-being of the community through the cost effective provision and development of a public art museum, to maximise enjoyment of visual art exhibitions, and to promote public appreciation of Canterbury art, and more widely, the national cultural heritage by collecting, conserving, researching and disseminating knowledge about art. -

![COLIN Mccahon [1919-1987 Aotearoa New Zealand] ANNE Mccahon (Née HAMBLETT) [1915-1993 Aotearoa New Zealand]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4998/colin-mccahon-1919-1987-aotearoa-new-zealand-anne-mccahon-n%C3%A9e-hamblett-1915-1993-aotearoa-new-zealand-1794998.webp)

COLIN Mccahon [1919-1987 Aotearoa New Zealand] ANNE Mccahon (Née HAMBLETT) [1915-1993 Aotearoa New Zealand]

COLIN McCAHON [1919-1987 Aotearoa New Zealand] ANNE McCAHON (née HAMBLETT) [1915-1993 Aotearoa New Zealand] [Paintings for Children] 1944 Ink, pen, watercolour on paper Private Collection [Harbour Scene - Paintings for Children] 1944 Ink, pen, watercolour on paper Collection of the Forrester Gallery. Gifted by the John C. Parsloe Trust. [Ships and Planes – Paintings for Children] 1944 Ink, pen, watercolour on paper Private Collection, Wellington Colin McCahon met fellow artist Anne Hamblett in 1937 while both studying at the Dunedin School of Art. The couple married on 21 September 1942 and went on to have four children. In the mid-1940s, Anne began a sixteen-year long career as an illustrator, often illustrating children’s books, such as At the Beach by Aileen Findlay, published in 1943. During this time, the McCahons collaborated on the series known as Paintings for Children. This would be the first and only time the couple would produce work together. The subject-matter was divided among the two, Colin was responsible for the landscape, while Anne filled each scene with bustling activity, including buildings, trains, ships, cars and people. These works were exhibited at Dunedin’s Modern Books, a co-operative book shop, in November 1945. This exhibition received positive praise from an Art New Zealand reviewer, who said: “These pictures are the purest fun: red trains rushing into and out from tunnels, through round green hills, and over viaducts against clear blue skies; bright ships queuing up for passage through amazing canals or diligently unloading at detailed wharves, people and horses and aeroplanes overhead all very serious and busy… They will be lucky children indeed who get these pictures – too lucky perhaps because the pictures should be turned into picture books and then every good child might have the lot.” 1 Two years later, in 1947, a group of Colin McCahon’s new paintings were also exhibited at Modern Books. -

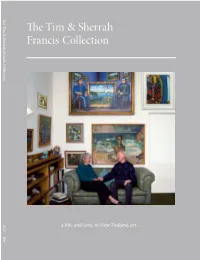

The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection

The Tim & Sherrah FrancisTimSherrah & Collection The The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection A+O 106 a life, and love, in New Zealand art… The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection Art + Object 7–8 September 2016 Tim and Sherrah Francis, Washington D.C., 1990. Contents 4 Our Friends, Tim and Sherrah Jim Barr & Mary Barr 10 The Tim and Sherrah Francis Collection: A Love Story… Ben Plumbly 14 Public Programme 15 Auction Venue, Viewing and Sale details Evening One 34 Yvonne Todd: Ben Plumbly 38 Michael Illingworth: Ben Plumbly 44 Shane Cotton: Kriselle Baker 47 Tim Francis on Shane Cotton 53 Gordon Walters: Michael Dunn 64 Tim Francis on Rita Angus 67 Rita Angus: Vicki Robson 72 Colin McCahon: Michael Dunn 75 Colin McCahon: Laurence Simmons 79 Tim Francis on The Canoe Tainui 80 Colin McCahon, The Canoe Tainui: Peter Simpson 98 Bill Hammond: Peter James Smith 105 Toss Woollaston: Peter Simpson 108 Richard Killeen: Laurence Simmons 113 Milan Mrkusich: Laurence Simmons 121 Sherrah Francis on The Naïve Collection 124 Charles Tole: Gregory O’Brien 135 Tim Francis on Toss Woollaston Evening Two 140 Art 162 Sherrah Francis on The Ceramics Collection 163 New Zealand Pottery 168 International Ceramics 170 Asian Ceramics 174 Books 188 Conditions of Sale 189 Absentee Bid Form 190 Artist Index All quotes, essays and photographs are from the Francis family archive. This includes interviews and notes generously prepared by Jim Barr and Mary Barr. Our Friends, Jim Barr and Mary Barr Tim and Sherrah Tim and Sherrah in their Wellington home with Kate Newby’s Loads of Difficult. -

The Evangelist How the Light Gets in the Christian Art of Colin Mccahon

The Evangelist the exodus from Egypt (Exodus 3:14). The texts, from the Psalms, included a prayer for self-awareness: I first encountered a Colin McCahon painting in the ‘teach us to order our days rightly, that we may enter mid 1970s when I was Ecumenical Chaplain at Victoria the gate of wisdom’ (Psalm 90:12),2 and an invocation University of Wellington. A gigantic mural appeared of God’s blessing: ‘God be gracious to us and bless us, on the wall of the entrance foyer of a new lecture God make his face shine upon us that his ways may block—now known as the Maclaurin Building. It be known on earth and his saving power among all the featured an enormous 3 metre-high ‘I AM’ in white nations’ (Psalm 67:1-2). and black letters, astride a stylised but recognisably New Zealand landscape, with texts reminiscent of the I remember standing before this vast mural, awed biblical prophets. by its impact. It was a profoundly counter-cultural It was a painting to walk past, from left to right. The statement—not unlike the ‘turn or burn’ preaching left panel, showing the lowering darkness of a bush of the Jesus People movement with which it is fire or an approaching storm, seemed heavy with contemporary—warning that our secular, materialistic How the light gets in The Christian art of Colin McCahon foreboding about secular culture, ‘this dark night of society will destroy itself, unless we humble Western civilisation’. It reminded me of the words of ourselves, seek wisdom, and pursue ‘the Lord, our true Fairburn, who a generation earlier had also lamented goal’. -

Download PDF Catalogue

THE 21st CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE A+O 7 A+O THE 21st CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE 3 Abbey Street, Newton PO Box 68 345, Newton Auckland 1145, New Zealand Phone +64 9 354 4646 Freephone 0800 80 60 01 Facsimile +64 9 354 4645 [email protected] www.artandobject.co.nz Auction from 1pm Saturday 15 September 3 Abbey Street, Newton, Auckland. Note: Intending bidders are asked to turn to page 14 for viewing times and auction timing. Cover: lot 256, Dennis Knight Turner, Exhibition Thoughts on the Bev & Murray Gow Collection from John Gow and Ben Plumbly I remember vividly when I was twelve years old, hopping in the car with Dad, heading down the dusty rural Te Miro Road to Cambridge to meet the train from Auckland. There was a special package on this train, a painting that my parents had bought and I recall the ceremony of unwrapping and Mum and Dad’s obvious delight, but being completely perplexed by this ‘artwork’. Now I look at the Woollaston watercolour and think how farsighted they were. Dad’s love of art was fostered at Auckland University through meeting Diane McKegg (nee Henderson), the daughter of Louise Henderson. As a student he subsequently bought his first painting from Louise, an oil on paper, Rooftops Newmarket. After marrying Beverley South, their mutual interest in the arts ensured the collection’s growth. They visited exhibitions in the Waikato and Auckland and because Mother was a soprano soloist, and a member of the Hamilton Civic Bev and Murray Gow Choir, concert trips to Auckland, Tauranga, New Plymouth, Gisborne and other centres were in their Orakei home involved. -

A LAND of GRANITE: Mccahon and OTAGO

1 A LAND OF GRANITE: McCAHON AND OTAGO DUNEDIN PUBLIC ART GALLERY COLIN McCAHON OTAGO PENINSULA 1946-1949. OIL AND GESSO ON BOARD. COLLECTION OF DUNEDIN PUBLIC LIBRARIES KĀ KETE WĀNAKA O ŌTEPOTI, RODNEY KENNEDY BEQUEST. COURTESY OF THE COLIN McCAHON RESEARCH AND PUBLICATION TRUST 7 MARCH - 18 OCT 2020 Otago has a calmness, a coldness, almost a classic geological order. It is, perhaps, A LAND OF an Egyptian landscape, a land of calm orderly granite. ...Big hills stood in front of GRANITE: FREE ADMISSION: OPEN 10AM-5PM DAILY P. +64 3 474 3240 E. [email protected] the little hills, which rose up distantly across the plain from the flat land: there 30 The Octagon Dunedin 9016 A department of the Dunedin City Council McCAHON www.dunedin.art.museum was a landscape of splendour, and order and peace. [Colin McCahon, Beginnings Landfall 80 p.363-64 December 1966] Exhibition Partner AND OTAGO This guide was originally produced as a double-sided A1 poster for the exhibition A Land of Granite: McCahon and Otago (Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 7 March – 18 October 2020). Above is the front side of the poster and following are the texts and images from the reverse side of the poster. The reverse side has been reformated to this A4 document for either reading online or downloading and printing. The image above is: COLIN McCAHON Otago Peninsula 1946-1949 Oil on gesso on board Collection of Dunedin Public Libraries Kā Kete Wānaka o Ōtepoti, Rodney Kennedy bequest. Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust 2 A LAND OF GRANITE: McCAHON AND OTAGO A LAND OF GRANITE: DUNEDIN PUBLIC ART GALLERY McCAHON AND OTAGO A Land of Granite: Colin McCahon and Otago was developed by Dunedin Public Art Gallery.