Lessons in Ephemera: Teaching and Learning Through Cultural Heritage Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

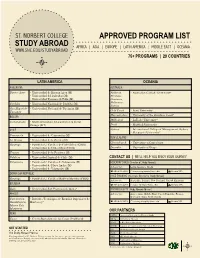

Approved Program List Study Abroad

ST. NORBERT COLLEGE APPROVED PROGRAM LIST STUDY ABROAD AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | OCEANIA WWW.SNC.EDU/STUDYABROAD 4 75+ PROGRAMS | 29 COUNTRIES LATIN AMERICA OCEANIA ARGENTINA AUSTRALIA Buenos Aires • Universidad de Buenos Aires (M) Ballarat, • Australian Catholic University* • Universidad del Salvador (M) Brisbane, • Universidad Torcuato di Tella (M) Canberra, Melbourne, Córdoba • Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (M) Sydney San Miguel de • Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (M) Gold Coast • Bond University Tucumán Maroochydore • University of the Sunshine Coast* BOLIVIA Melbourne • LaTrobe University* Cochabamba • Multiculturalism, Globalization & Social Change (SIT) Perth • Murdoch University CHILE Sydney • International College of Management, Sydney • Macquarie University* Concepción • Universidad de Concepción (M) NEW ZEALAND La Serena • Universidad de la Serena (M) Christchurch • University of Canterbury Santiago • Pontificia U. Católica de Chile (M) or (CIEE) • Universidad de Chile (M) or (CIEE) Dunedin • University of Otago Temuco • Universidad de la Frontera (M) Valdivia • Universidad Austral de Chile (M) CONTACT US | WE’LL HELP YOU ENJOY YOUR JOURNEY Valparaíso • Pontificia U. Católica de Valparaíso (M) ROSEMARY SANDS (Director of Study Abroad) • Universidad de Playa Ancha (M) Advisor for: Latin America; Spain • Universidad de Valparaíso (M) ( 920.403.4068 8 [email protected] Bemis 323 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC JOYCE TULLBANE (Associate Director of Study Abroad) Santiago • Pontificia U. Católica Madre y -

Key Statistics 2019

Pacific Ethnicities* 800+ Pacific Students Pacific Graduates per Year KEY STATISTICS 4,118 by Headcount 2019 134 Pacific PhDs since 2001 Gender Male 1,361 383 734 225 Female 2,744 Cook Islands Fiji Niue 274 (Headcount) Diverse 13 Full Time Student Workload (Headcount) 2017 2018 2019 Equivalent Staff Full Time 2,466 2,566 2,505 59 215 Part Time 1,577 1,567 1,613 (FTE) Academic Professional Total 4,043 4,133 4,118 1,846 39 1,037 Samoa Tokelau Tonga Gender Tertiary Provider Pacific Undergraduate EFTS Female 189 University of Auckland 2,316 Male 85 Other Pacific Island (FTE) Auckland University of Technology 2,480 254 University of Otago 542 * the number of students associated with each ethnicities. For example, a student who is both Samoan and Victoria University of Wellington 521 Cook Island Maori will be counted towards both flags. Massey University 442 University of Waikato 445 University of Canterbury 233 3,194 Lincoln 23 NEW ZEALAND’S TOP RANKED Equivalent Full-Time * Pacific Postgraduate EFTS by Tertiary Providers UNIVERSITY Students (EFTS) University of Auckland *QS World University Rankings 2019 Auckland University of Technology Pacific Islands Student Enrolments 2017 2018 2019 Massey University Equivalent Full-Time Students (EFTS) 3,146 3,233 3,194 Victoria University of Wellington By Course Funding Level (EFTS) University of Otago Degree 2,548 2,610 2,589 University of Waikato IN NEW ZEALAND University of Canterbury Non-Degree 172 170 154 for 37 of the 41 subjects Research Postgraduate 99 110 111 Lincoln in which we are ranked* -

International Prospectus Aotearoa | New Zealand ‘UC PROVIDES EVERYTHING: Connections, Opportunities, Community Service, and Brilliant Learning.’ — Rishi, India

2022 International Prospectus Aotearoa | New Zealand ‘UC PROVIDES EVERYTHING: connections, opportunities, community service, and brilliant learning.’ — Rishi, India Contents Why UC? Enrol at UC Study options 1 Welcome to UC 15 Am I eligible? 29 Arts 2 UC7 16 UC Undergraduate entry 34 Business 4 Why UC? requirements 36 Education 6 Support services 18 Choose an undergraduate 38 Engineering 8 Why Ōtautahi Christchurch? qualification 41 Health 10 Life in Ōtautahi Christchurch 20 Pathways to UC 43 Law 12 Why Aotearoa New Zealand? 21 How much will it cost? 44 Science 22 Visas and insurance 48 Online study support 49 Next steps UC lifestyle Rainbow Diversity Support 24 Where will I live? 25 A unique experience UC is proud to partner with Ngāi Tūāhuriri and Ngāi Tahu to uphold the mana and aspirations of mana whenua. Information is correct at the time of print but is subject to change. You are welcome at UC When we ask our students what Our internships, placements, and makes UC different, they tell us this is industry connections will help you a pretty special place to study and live. grow your employability opportunities in Aotearoa New Zealand and Our leafy green campus is nestled international markets. between moana (sea), maunga (mountains), and rangi (sky), offering Importantly, there are many unique experiences like UC’s opportunities to make new friends (join Mt John Observatory, one of the few one of our amazing clubs) and create dark sky reserves in the world. The unforgettable memories in Aotearoa. campus itself with the Ōtākaro Avon Kia ora koutou Experience kotahitanga (togetherness), River winding through provides a manaakitanga (caring for each other) and There is no doubt about it; the world place for you to breathe. -

Family Experiments Middle-Class, Professional Families in Australia and New Zealand C

Family Experiments Middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c. 1880–1920 Family Experiments Middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c. 1880–1920 SHELLEY RICHARDSON Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Richardson, Shelley, author. Title: Family experiments : middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c 1880–1920 / Shelley Richardson. ISBN: 9781760460587 (paperback) 9781760460594 (ebook) Series: ANU lives series in biography. Subjects: Middle class families--Australia--Biography. Middle class families--New Zealand--Biography. Immigrant families--Australia--Biography. Immigrant families--New Zealand--Biography. Dewey Number: 306.85092 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. The ANU.Lives Series in Biography is an initiative of the National Centre of Biography at The Australian National University, ncb.anu.edu.au. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Photograph adapted from: flic.kr/p/fkMKbm by Blue Mountains Local Studies. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents List of Illustrations . vii List of Abbreviations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Introduction . 1 Section One: Departures 1 . The Family and Mid-Victorian Idealism . 39 2 . The Family and Mid-Victorian Realities . 67 Section Two: Arrival and Establishment 3 . The Academic Evangelists . 93 4 . The Lawyers . 143 Section Three: Marriage and Aspirations: Colonial Families 5 . -

1 Matthias Heyne Curriculum Vitae Boston University

CV Matthias Heyne - Last updated: September 2018 Matthias Heyne Curriculum Vitae Boston University - Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences Department of Speech, Language & Hearing Sciences 677 Beacon St., Boston, MA 02215 Speech Neuroscience Laboratory [email protected]; +1 617 800 7669 http://languageandmusic.info Research Interests neuroscience of speech production, real-time MRI of the vocal tract, language and music, articulatory phonetics, ultrasound imaging of the tongue, sociophonetics, New Zealand English Education & Research Positions 2017- Postdoctoral Research Associate, Boston University Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences Speech Neuroscience Laboratory Advisors: Prof. Frank Guenther & Dr. Jason Tourville 2017 Helsinki Summer School, course Auditory Cognitive Neuroscience 6 ECTS, August 9 to 18, 2017 2016 Ph.D. in Linguistics, University of Canterbury, New Zealand Dissertation: The influence of First Language on playing brass instruments: An ultrasound study of Tongan and New Zealand trombonists, Advisors: Dr. Donald Derrick & Prof. Jennifer Hay 2012 State Exam “Teaching for secondary schools” (1. Staatsexamen) with the subjects Music and English, University of the Saarland and University of Music Saar, Saarbrücken, Germany Thesis in English Linguistics: The interaction of musicians in rehearsals Advisor: Prof. Dr. Neal R. Norrick 2012 “Jazz – complementary studies” Trombone (Diplom- Ergänzungsstudiengang Jazz), University of Music Saar 2010 Study abroad semester, University of Melbourne, Australia Linguistics classes taken: Language and Identity Language in Aboriginal Australia 2010 “Orchestral Music” (performance) Bass Trombone (Diplom Orchestermusik), University of Music Saar 2004-2007 Studies at the Mannheim University of Music and Performing Arts, Germany, in the courses “Diploma in music teaching” (for music schools) and “Instrumental Performance“ (Bass Trombone) Peer-reviewed Publications Heyne, M., Wang, X., Derrick, D., Dorreen, K., & Watson, K. -

Approved Unaffiliated Programs (Aups) 2022-2023 Terms Abroad

Approved Unaffiliated Programs (AUPs) 2022-2023 Terms Abroad Approved Unaffiliated Programs (AUPs) are pre-approved for transfer of credit back to the University of Denver. DU students must successfully complete the DU Study Abroad nomination process by indicated deadlines in order to receive approval to participate on an AUP. AUPs are approved based on the accredited institution issuing the transcript for student coursework abroad. In the case of some foreign institutions listed below, it may be possible for a student to enroll in the institution via a U.S. program provider (IES, CIEE, CEA, g-MEO, IGE, USAC, etc.); in doing so, it is the student's responsibility to verify that the program provider selected offers a transcript from the institution indicated below, otherwise DU may deny transfer of credit for the program. In the case of U.S. institutions that conduct their own programs abroad or serve as a school of record, transcripts from these institutions are approved ONLY for the study abroad program(s) indicated. Transcripts from these institutions for study abroad programs other than those indicated on the AUP list are not approved for transfer credit. Because of the fluid nature of health and safety abroad, all approved programs below may be reviewed by Risk Management after application and may not be approved based upon the security/health situation of the country or region. Study Abroad Program Transcript Institution Country Summer Only: Critical Language Scholarship Bryn Mawr College (SoR*) various School for Field Studies University -

University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand

2020 International Programme Flyer Your direct pathway to the University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand UCIC Students, The Engineering Core, UC Campus Welcome to Welcome to New Zealand UC International College UCIC Students, UCIC Students, UC Campus Sumner Beach Christchurch 1 #1 in the World 5 3-year Post-study Work Visa Studying at UC International College (UCIC), you will have a pathway to a New Zealand is the #1 English-speaking country International students can apply for a post-study world-class University of Canterbury (UC) degree.* in the world for preparing students for the future. work visa to work for any employer in almost any job in Source: Economist Intelligence Unit Educating for the Future Index 2018. New Zealand. • Alternative pathway from high school to Length of stay: 3 years for Level 7 Bachelor's degree undergraduate studies or higher; 2 or 3 years if students complete their study • Pathway options to all UC’s bachelor degrees 2 Learn in English outside Auckland before the end of 2021. • Save time and money over traditional foundation studies pathway programmes English is one of three official languages in Source: immigration.govt.nz. I want New Zealand. Studying here will improve international • Study with experienced staff in small classes students’ workplace-relevant English language skills. • More contact hours with teachers and classmates to support your academic success 6 1st Code of Practice • Academic study skill support throughout your programme 3 Better CV New Zealand was the first country in the world to adopt a code of practice for the • All programmes delivered on the beautiful UC campus with access to world-class facilities New Zealand Qualifications are recognised and care of international students. -

E-Readers: Devices for Passionate Leisure Readers Or an Empowering Scholarly Resource?

E-readers: devices for passionate leisure readers or an empowering scholarly resource? Peter Lund1, Katie Appleton2, Bryan Dawson2, Nick Loakes3, Ann O’Brien3 1. Learning Resources, University of Canterbury, formerly Loughborough University Library, UK. 2. Loughborough University Library, Loughborough, UK. 3. Department of Information Science, Loughborough University, UK. Acknowledgements Dr Gabriel Egan4 and Emma Clift4, Dave Clemens5, Deborah Fitchett5, Catherine Jane5, 4. Department of English and Drama, Loughborough University, UK. 5. Learning Resources, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand Summary E-books are increasingly common in academic libraries and e-book reading devices such as the Kindle and iPad are achieving huge sales for leisure readers. The authors undertook a small study at Loughborough University Library to explore areas in which a variety of e-book readers might be applied. Areas included: e-books on reading lists, PDFs of journal articles, inter-library loans supplied from the British Library and teaching support for Shakespeare studies. Whilst the e-readers did not offer sufficient advantages to merit integrating them into a service, the study proved useful in developing library expertise in the use of and support for e-readers. Introduction E-books are becoming more common in academic libraries for a number of reasons. They may be attractive to Library management since they can be acquired quickly, are easier to store and offer huge space saving advantages. There is the convenience of 24/7 access and if you happen to be a librarian in earthquake-torn Christchurch, they may offer the only alternative to the paper versions stored in libraries suffering temporary closure. -

1-CJW June 2014 CURRICULUM VITAE CHRISTOPHER J. WALLER

June 2014 CURRICULUM VITAE CHRISTOPHER J. WALLER OFFICE ADDRESS Department of Economics and Econometrics 434 Flanner Hall University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, IN 46556-5602 Phone: (574)-631-4963 Email: [email protected] Web address: http://www.nd.edu/~cwaller/ EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, 1985 Master of Arts, 1984 Washington State University, Pullman, WA Bachelor of Science, 1981 Bemidji State University, Bemidji, MN MAJOR FIELDS OF INTEREST Monetary Theory, Political Economy, Macroeconomic Theory PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Currently Senior Vice President and Research Director, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (effective June 1, 2009) Professor of Economics, University of Notre Dame (On leave). 2012, Fall Sam Cook Visiting Professor, Washington University-St. Louis. 2003-2011 Gilbert F. Schaefer Chair of Economics Research Fellow, Nanovic Institute of European Studies and the Kellogg Institute for International Studies 1-CJW June 2014 University of Notre Dame 2006 – 2007 Acting Department Chair, Dept. of Economics and Econometrics, University of Notre Dame. 2006, Summer Erskine Fellow, University of Canterbury, New Zealand 1998 – 2003 Professor and Carol Martin Gatton Chair of Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics, University of Kentucky. Research Fellow, Center for European Integration Studies (ZEI), University of Bonn. 1998 – 2004 Visiting Professor, EERC, National University of Kiev-Mohyla Academy, Kiev, Ukraine. 1994 – 1995 Visiting Scholar, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and Washington University. 1994, Summer Visiting Scholar, University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany. 1994, May Visiting Scholar, International Finance Division, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 1992 – 1994 Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Economics, Indiana University. 1992 – 1998 Associate Professor Economics, Indiana University. -

Department of Marketing and Development

University of Canterbury Financial requirement The University of Canterbury has no specific financial requirements for exchange students. Estimated costs of living can be found at: http://www.canterbury.ac.nz/international/costs/living.shtml However, when exchange students apply for a student visa, Immigration New Zealand (INZ) requires proof of funds for living expenses, please see: www.immigration.govt.nz/migrant/stream/study/canistudyinnewzealand/whatisrequired/ Brief overview of the university Established in 1873 by scholars from Oxford and Cambridge, the University of Canterbury, in Christchurch, New Zealand, has an international reputation for academic excellence in both teaching and research. Christchurch is the largest city in New Zealand’s South Island. It lies on the coastal edge of the Canterbury Plains close to both the sea and the mountains. The University’s modern and well- equipped facilities are spread across a spacious suburban campus, with easy access to the centre of the city and its cultural and recreational facilities. The University is situated in a spacious landscaped campus in the suburb of Ilam, Christchurch, only 15 minutes from the central city and 10 minutes from the International Airport. The campus is surrounded by playing fields, mature woodlands and the renowned Ilam gardens. Academic issues Academic strengths http://www.canterbury.ac.nz/international/about/facts.shtml Restricted/closed . Distance learning courses, Fine Arts , Journalism, MBA, All clinical practice courses Departments . Communication Disorders are open to students who meet pre-requisites except for the clinical practice courses. Social Work – field work courses are not open to Exchange students. Entry to other theory courses will be considered case-by-case basis and approval from Social Work will be required. -

List of Names

Organizing Committee GENERAL CHAIRS CONTEST CHAIRS PUBLICATIONS CHAIRS WEB CHAIRS Joaquim Jorge Daniel Roth Christos Mousas Maurício Sousa Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal Technical University of Munich, Germany Purdue University, USA University of Toronto, Canada Kyle Johnsen Chao Mei Mohammed Safayet Arefin Jiannan Li University of Georgia, USA Kennesaw State University, USA Mississippi State University, USA University of Toronto, Canada J. Edward Swan II Luciano Soares PUBLICITY CHAIRS Catarina Fidalgo Mississippi State University, USA Insper, Brazil John Quarles University of Lisbon, Portugal University of Texas San Antonio, USA Pedro Campos DOCTORAL CONSORTIUM J. Adam Jones University of Madeira, Portugal CHAIRS Nami Ogawa University of Mississippi, USA University of Tokyo, Japan JOURNAL PAPER PROGRAM Andrew Robb WORKSHOPS CHAIRS Clemson University, USA CHAIRS RESEARCH João Pereira Maud Marchal Teresa Romão DEMONSTRATIONS CHAIRS INESC-ID/University of Lisbon, Portugal University of Rennes, INSA/IRISA, Nova University Lisbon, Portugal Ayush Bhargava France Sabine Coquillart Key Lime Interactive, USA Aleshia Hayes INRIA Grenoble Rhône-Alpes, France Tabitha Peck University of North Texas, USA David Krum Davidson College, USA Jason Gerald California State University, USA Rajiv Khadka NextGen Interactions, USA Stephan Lukosch Idaho National Laboratory, USA Benjamin Weyers University of Canterbury, New Zealand Mashhuda Glencross University of Trier, Germany ONLINE CONFERENCE University of Queensland, Australia Xubo Yang CHAIRS Rafael Kuffner -

University of Canterbury, New Zealand

University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand Associate Professor David G. Wareham Associate Dean International College of Engineering The University of Canterbury 1. Introduce the University 2. The Structure of the Engineering Degree 3. Talk about the Various Degrees Offered within the College of Engineering 4. Some Points of Demarcation of Engineering at UC 5. Additional Factors Associated with UC Associate Professor David G. Wareham Associate Dean International College of Engineering Christchurch, New Zealand Population: • New Zealand - 4 500 000 • Christchurch – 366 000 • Known as the ‘Garden City’ • Near the beach and five ski fields • Lonely Planet has named Christchurch in sixth place in its Best in Travel 2013: Top 10 Cities. University of Canterbury • Established in 1873, Canterbury College, as the University was originally known, was only the second university in New Zealand • Ernest Rutherford, Canterbury’s most distinguished graduated, studied at the University in the 1890s • 2000 courses • 14,700 students • 726 academic staff University of Canterbury • We are a residential campus!! • 1800 international students • Students from over 93 countries Structure of the UC Engineering Degree Associate Professor David G. Wareham Associate Dean International College of Engineering Bachelor of Engineering with Honours - BE(Hons) Four-year honours degree Engineering Intermediate Year • 5 common required courses • 4 other approved courses (depends on intended discipline) • Unique opportunity to keep options open in first year • First