Survey of Minority Officers in the Navy: Attitudes and Opinions on Recruiting and Retention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

QUARTERMASTER CHIEF PETTY OFFICER (Navigation and Ship Handling Master)

QUARTERMASTER RATING ROADMAP January 2012 CAREER ROADMAP Seaman Recruit to Master Chief Roadmaps The educational roadmap below will assist Sailors in the Quartermaster community through the process of pursuing professional development and advanced education using various military and civilian resources e.g. PQS program; SMART Transcript; NKO (E-Learning); Navy College; etc. Successful leadership is the key to military readiness and will always require a high degree of technical skill, professional knowledge, and intellectual development. What is a Career Roadmap for Quartermaster? Quartermaster roadmaps are just what the name implies – a roadmap through the Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum from Quartermaster Seaman Recruit through Quartermaster Master Chief. The principal focus is to standardize a program Navywide by featuring the existing skills of Quartermaster necessary to be successful in the Navy. The ultimate goal of a roadmap is to produce a functional and competent Quartermaster. What is the Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum? Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum is the formal title given to the curriculum and process building on the foundation of Sailorization beginning in our Delayed Entry Program through Recruit Training Command and throughout your entire career. The continuum combines skill training, professional education, well-rounded assignments, and voluntary education. As you progress through your career, early-on skill training diminishes while professional military education gradually increases. Experience is the ever-present constant determining the rate at which a Sailor trades skill training for professional development. Do Sailors have to follow the Roadmap? Yes. The Quartermaster roadmap includes the four areas encompassed by the Continuum in Professional Military Education to include; Navy Professional Military Education, Joint Professional Education, Leadership and Advanced Education. -

Open Drane Dissertation.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School AN ORAL HISTORY OF THE NAVY BAND B-1: THE FIRST ALL-BLACK NAVY BAND OF WORLD WAR II A Dissertation in Music Education by Gregory Abdul Drane © 2020 Gregory Abdul Drane Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 ii The dissertation of Gregory Abdul Drane was reviewed and approved* by the following: O. Richard Bundy, Jr. Professor of Music Education, Emeritus Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Robert Gardner Associate Professor of Music Education David McBride Professor of African American Studies and African American History Ann Clements Professor of Music Education Linda Thornton Professor of Music Education Chair of the Graduate Program iii ABSTRACT This study investigates the service of the Navy Band B-1, the first all-black Navy band to serve during World War II. For many years it was believed that the black musicians of the Great Lakes Camp held the distinction as the first all-black Navy band to serve during World War II. However, prior to the opening of the Navy’s Negro School of Music at the Great Lakes Camps, the Navy Band B-1 had already completed its training and was in full service. This study documents the historical timeline of events associated with the formation of the Navy Band B-1, the recruitment of the bandsmen, their service in the United States Navy, and their valuable contributions to the country. Surviving members of the Navy Band B-1 were interviewed to share their stories and reflections of their service during World War II. -

The United States Navy Looks at Its African American Crewmen, 1755-1955

“MANY OF THEM ARE AMONG MY BEST MEN”: THE UNITED STATES NAVY LOOKS AT ITS AFRICAN AMERICAN CREWMEN, 1755-1955 by MICHAEL SHAWN DAVIS B.A., Brooklyn College, City University of New York, 1991 M.A., Kansas State University, 1995 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2011 Abstract Historians of the integration of the American military and African American military participation have argued that the post-World War II period was the critical period for the integration of the U.S. Navy. This dissertation argues that World War II was “the” critical period for the integration of the Navy because, in addition to forcing the Navy to change its racial policy, the war altered the Navy’s attitudes towards its African American personnel. African Americans have a long history in the U.S. Navy. In the period between the French and Indian War and the Civil War, African Americans served in the Navy because whites would not. This is especially true of the peacetime service, where conditions, pay, and discipline dissuaded most whites from enlisting. During the Civil War, a substantial number of escaped slaves and other African Americans served. Reliance on racially integrated crews survived beyond the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, only to succumb to the principle of “separate but equal,” validated by the Supreme Court in the Plessy case (1896). As racial segregation took hold and the era of “Jim Crow” began, the Navy separated the races, a task completed by the time America entered World War I. -

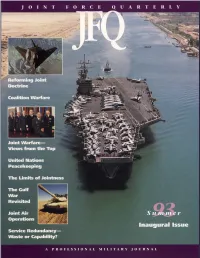

JFQ 11 ▼JFQ FORUM Become Customer-Oriented Purveyors of Narrow NOTES Capabilities Rather Than Combat-Oriented Or- 1 Ganizations with a Broad Focus and an Under- U.S

Warfare today is a thing of swift movement—of rapid concentrations. It requires the building up of enormous fire power against successive objectives with breathtaking speed. It is not a game for the unimaginative plodder. ...the truly great leader overcomes all difficulties, and campaigns and battles are nothing but a long series of difficulties to be overcome. — General George C. Marshall Fort Benning, Georgia September 18, 1941 Inaugural Issue JFQ CONTENTS A Word from the Chairman 4 by Colin L. Powell Introducing the Inaugural Issue 6 by the Editor-in-Chief JFQ FORUM JFQ Inaugural Issue The Services and Joint Warfare: 7 Four Views from the Top Projecting Strategic Land Combat Power 8 by Gordon R. Sullivan The Wave of the Future 13 by Frank B. Kelso II Complementary Capabilities from the Sea 17 by Carl E. Mundy, Jr. Ideas Count by Merrill A. McPeak JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY 22 JFQ Reforming Joint Doctrine Coalition Warfare What’s Ahead for the Armed Forces? by David E. Jeremiah Joint Warfare— Views from the Top 25 United Nations Peacekeeping The Limits of Jointness The Gulf War Service Redundancy: Waste or Hidden Capability? Revisited Joint Air Summer Operations 93 by Stephen Peter Rosen Inaugural Issue 36 Service Redundancy— Waste or Capability? A PROFESSIONAL MILITARY JOURNAL ABOUT THE COVER Reforming Joint Doctrine The cover shows USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, 40 by Robert A. Doughty passing through the Suez Canal during Opera- tion Desert Shield, a U.S. Navy photo by Frank A. Marquart. Photo credits for insets, from top United Nations Peacekeeping: Ends versus Means to bottom, are Schulzinger and Lombard (for 48 by William H. -

AH197710.Pdf

1 SPRUANCE CLASS DESTROYERS- USS Paul F. Foster (DD 964),USS Elliot (DD 967) and USS Hewitt (DD 966)- berthedat the Naval Station, Sun Diego. (Photo by PHCS Herman Schroeder, USN(Ret)) r ALL MAGAZINE OF THE U.S. NAVY - 55th YEAR OF PUBLICATION 1977 NUMBEROCTOBER 1977 729 Features 4 'MYLETTERS RUFFLEDFEATHERS He was the first black to be commissioned in the regular Navy 8 GETTING TOGETHERAFTER MORE THAN THREE DECADES Their grueling determination paid off handsomely 12 COMMAND ORGANIZATION AND STAFF STRUCTURE Pane FOR THE OPERATING FORCES OF THE U.S. NAVY Explaining the two co-existing fleetcommand structures 16 FISHING FOR SUBMARINES OFF ICELAND A 15-hour mission is the norm when it comes to ASW 24 BASICUNDERWATER DEMOLITION AND SEA-AIR- LAND TRAINING Only half of them make it through Phase I 29 USS MARVIN SHIELDS VISITS WESTERN SAMOA Helping to celebratean island nation's independence 34 RESERVECENTER ASSISTS FLOOD VICTIMS . .and again,disaster strikes this Pennsylvania town Departments 2 Currents 14 Grains of Salt 38 Bearings 42 For the Navy Buff 47 Mail Buoy Chiefof Naval Operations: Admiral James L. Holloway Ill Staff: LT Bill Ray Chief of Information: Rear Admiral David M.Cooney JOC Dan Guzman Dir. Print Media Div. (NIRA): Lieutenant Commander G. Wm. Eibert JO1 John Yonemura Editor: John F. Coleman JO1 Jerry Atchison Production Editor: Lieutenant John Alexander JO1 (SS)Pete Sundberg Layout Editor: E. L. Fast PH1 Terry Mitchell ArtEditor: Michael Tuffli JO2 Dan Wheeler JO2 Davida Matthews J03 Francis Bir Edward Jenkins Elaine McNeil Covers Front: Excellent timing by PH2 R. -

Aviation Structural Mechanic

Aviation Structural Mechanic RATING ROADMAP 1 Jan 2011 CAREER ROADMAP Airman Recruit to Master Chief Roadmaps The educational roadmap below will assist Sailors in the Aviation Structural Mechanic (AM) community through the process of pursuing professional development and advanced education using various military and civilian resources e.g. PQS program; SMART Transcript; NKO (E-Learning); Navy College; etc. Successful leadership is the key to military readiness and will always require a high degree of technical skill, professional knowledge, and intellectual development. What is a Career Roadmap for Aviation Structural Mechanic’s? AM roadmaps are just what the name implies – a roadmap through the Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum from AM Airman Recruit through AM Master Chief. The principal focus is to standardize a program Navy wide by featuring the existing skills necessary for AM’s to be successful in the Navy. The ultimate goal of a roadmap is to produce a functional and competent AM. What is the Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum? Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum is the formal title given to the curriculum and process building on the foundation of Sailorization beginning in our Delayed Entry Program through Recruit Training Command and throughout your entire career. The continuum combines skill training, professional education, well-rounded assignments, and voluntary education. As you progress through your career, early-on skill training diminishes while professional military education gradually increases. Experience is the ever-present constant determining the rate at which a Sailor trades skill training for professional development. Do Sailors have to follow the Roadmap? Yes. The AM roadmap includes the four areas encompassed by the Continuum in Professional Military Education to include; Navy Professional Military Education, Joint Professional Education, Leadership and Advanced Education. -

Proquest Dissertations

"Time, tide, and formation wait for no one": Culturaland social change at the United States Naval Academy, 1949-2000 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Gelfand, H. Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 07:31:17 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280180 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 "TIME, TIDE, AND FORMATION WATT FOR NO ONE": CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CHANGE AT THE UNITED STATES NAVAL ACADEMY, 1949-2000 by H. -

“Your Message Here”: an Analysis of the Us Navy in Photo Postcards

“YOUR MESSAGE HERE”: AN ANALYSIS OF THE U.S. NAVY IN PHOTO POSTCARDS by Stephanie Croatt April, 2013 Director of Thesis: John Tilley Major Department: Maritime Studies The purpose of this project is to analyze photographic postcards with images of the U.S. Navy between 1913 and 1945. This analysis will explore how the postcard images portray the Navy as powerful, competent, and happy. This portrayal became more pronounced over time, thanks to increasing photography training and censorship practices in the Navy. As a widely popular medium for the dissemination of “soft news” that would have recruited the public and enlisted population’s consent and support of the U.S. Navy’s activities, the photo postcards analyzed here demonstrate what kinds of messages the postcards would have conveyed. Photo postcards acted as evidence of the sailor’s activities abroad and of the Navy’s power in the form of ships and capable, numerous crews. While they offered proof of a powerful, capable Navy, the images would have also elicited pride and patriotism from the viewer. This, in turn, might have facilitated the civilian’s furthered support of war efforts or of retaining funding for the Navy during peacetime, and enticing more men to join the Navy. For men in the Navy, the pride invoked by postcard images may have helped define their identity as a member of the Navy. “YOUR MESSAGE HERE”: AN ANALYSIS OF THE U.S. NAVY IN PHOTO POSTCARDS A Thesis Presented To the Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Stephanie Croatt April, 2013 © Stephanie Croatt, 2013 “YOUR MESSAGE HERE”: AN ANALYSIS OF THE U.S. -

USS Midway Museum Library Online Catalog 01/01/2020

USS Midway Museum Library Online Catalog 01/01/2020 Author Title Pub Date Object Name Stevenson, James P. $5 Billion Misunderstanding, The : The Collapse of the Navy's A-12 Stealth Bomber 2001 Book Program Ross, Donald K. 0755 : The Heroes of Pearl Harbor 1988 Paperback Winkowski, Fredric 100 Planes, 100 Years : The First Century of Aviation 1998 Book Shores, Christopher 100 Years of British Naval Aviation 2009 Book Myers, Donald E. 101 Sea Stories : Those Tales Marines, Sailors and Others Love to Tell 2005 Paperback Bishop, Chris (ed) 1400 Days : The Civil War Day by Day 1990 Book Daughan, George C. 1812 : The Navy's War 2011 Book Werstein, Irving 1914-1918 : World War I Told with Pictures 1964 Paperback Hydrographic Office, Secretary of Navy 1931 International Code of Signals (American Edition), Vol. I - Visual 1952 Book Hydrographic Office, Secretary of Navy 1931 International Code of Signals (American Edition), Vol. II - Radio 1952 Book United States Naval Academy 1937 : The Sixty-Three Year Fix 2000 Paperback Kershaw, Andrew (ed) 1939-1945 War Planes 1973 Paperback Groom, Winston 1942 : The Year That Tried Men's Souls 2005 Book Naval Air Systems Command 2.75 Inch Airborne Rocket Launchers 1996 Manual Naval Air Systems Command 20-MM Aircraft Gun MK12 Mod 4 1980 Manual Naval Air Systems Command 20-MM Barrel Erosion Gage Kit M10(T23) 1976 Manual Merry, John A. 200 Best Aviation Web Sites 1998 Book Robinson, C. Snelling (Charles Snelling) 200,000 Miles Aboard the Destroyer Cotten 2000 Book Powell, Dick 20th Century Fox Studio Classics : 75 years, Disc 1 : On the Avenue 2006 DVD Grable, Betty 20th Century Fox Studio Classics : 75 years, Disc 2 : Pin Up Girl 2005 DVD Miranda, Carmen 20th Century Fox Studio Classics : 75 years, Disc 3 : Something for the Boys 2008 DVD Cooper, Gary 20th Century Fox Studio Classics : 75 years, Disc 4 : You're in the Navy Now 2006 DVD Murdock. -

Boatswain's Mate Rating Rating Roadmap

BOATSWAIN’S MATE RATING (BM) RATING ROADMAP January 2012 CAREER ROADMAP Seaman Recruit to Master Chief Roadmaps The inforamational roadmap will assist sailors in the BM Community through the process of personal and professional development and advanced education using various military and civilian resources e.g. PQS program; SMART Transcript; NKO (E-Learning); Navy College; etc. Successful leadership is the key to military readiness and will always require a high degree of technical skill, professional knowledge, and intellectual development. What is a Career Roadmap for BM? BM roadmaps are just what the name implies – a roadmap through the Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum from BM Seaman Recruit through BM Master Chief. The principal focus is to standardize a program Navy-wide by featuring the existing skills of a BM necessary to be successful in the Navy. The ultimate goal of a roadmap is to produce a functional and competent BM. What is the Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum? Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum is the formal title given to the curriculum and process building on the foundation of Sailorization beginning in our Delayed Entry Program through Recruit Training Command and throughout your entire career. The continuum combines skill training, professional education, well-rounded assignments, and voluntary education. As you progress through your career, early-on skill training diminishes while professional military education gradually increases. Experience is the ever-present constant determining the rate at which a Sailor trades skill training for professional development. Do Sailors have to follow the Roadmap? Yes. The BM roadmap includes the four areas encompassed by the Continuum in Professional Military Education to include; Navy Professional Military Education, Joint Professional Education, Leadership and Advanced Education. -

M E R Id Ia N

Pioneers in the naval Services WWW.NNOA.ORG MERIDIAN In this issue: 2—Mission to Haiti 4—Tidewater Chapter 6– Bayou Chapter 8—Military Diversity 10—DDG-107 Commissioned Magazine of theNational Naval Officers Association “GATEWAY TO SUCCESS” 1st Quarter 2011 On the Cover: Row 1: 1944—LTjg Harriet Ida Pickens (left) and ENS Frances Wills were the Navy's first African-American "WAVES" officers 1945—2ndLt Frederick C. Branch became the 1st African-American commissioned in the US Marine Corps 1943—LTJG Joseph C. Jenkins and LTJG Clarence Samuels were the first African-American Coast Guard officers 1944—―The Golden Thirteen", the first African-American U.S. Navy Officers They are (bottom row, left to right): Ensign James E. Hare, USNR; Ensign Samuel E. Barnes, USNR; Ensign George C. Cooper, USNR; Ensign William S. White, USNR; Ensign Dennis D. Nelson, USNR; (middle row, left to right): Ensign Graham E. Martin, USNR; Warrant Officer Charles B. Lear, USNR; Ensign Phillip G. Barnes, USNR; Ensign Reginald E. Goodwin, USNR; (top row, left to right): Ensign John W. Reagan, USNR; Ensign Jesse W. Arbor, USNR; Ensign Dalton L. Baugh, USNR; Ensign Frank E. Sublett, USNR. (U.S. NHHC Photograph) Row 2: 1998—RADM Erroll Brown, the first African-American promoted to flag rank in the U.S. Coast Guard 1945—Olivia Hooker was sworn in by a Coast Guard officer, becoming the first African-American female admitted into the U. S. Coast Guard 1971—LT Kenneth H. Johnson, founding member of the National Naval Officers Association 1979—LtGen Frank E. Petersen Jr. -

Quartermaster

QUARTERMASTER RATING ROADMAP January 2012 CAREER ROADMAP Seaman Recruit to Master Chief Roadmaps The educational roadmap below will assist Sailors in the Quartermaster community through the process of pursuing professional development and advanced education using various military and civilian resources e.g. PQS program; SMART Transcript; NKO (E-Learning); Navy College; etc. Successful leadership is the key to military readiness and will always require a high degree of technical skill, professional knowledge, and intellectual development. What is a Career Roadmap for Quartermaster? Quartermaster roadmaps are just what the name implies – a roadmap through the Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum from Quartermaster Seaman Recruit through Quartermaster Master Chief. The principal focus is to standardize a program Navywide by featuring the existing skills of Quartermaster necessary to be successful in the Navy. The ultimate goal of a roadmap is to produce a functional and competent Quartermaster. What is the Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum? Enlisted Learning and Development Continuum is the formal title given to the curriculum and process building on the foundation of Sailorization beginning in our Delayed Entry Program through Recruit Training Command and throughout your entire career. The continuum combines skill training, professional education, well-rounded assignments, and voluntary education. As you progress through your career, early-on skill training diminishes while professional military education gradually increases. Experience is the ever-present constant determining the rate at which a Sailor trades skill training for professional development. Do Sailors have to follow the Roadmap? Yes. The Quartermaster roadmap includes the four areas encompassed by the Continuum in Professional Military Education to include; Navy Professional Military Education, Joint Professional Education, Leadership and Advanced Education.