Productivity Commission Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Express (Rex) Response to the Productivity Commission Draft Report on the Economic Regulation of Airports

Regional Express (Rex) Response to the Productivity Commission Draft Report on the Economic Regulation of Airports 25 March 2019 Regional Express (Rex) Response to the Productivity Commission Draft Report on the Economic Regulation of Airports Table of Contents 1 OPENING STATEMENT 3 2 REGIONAL AIRPORTS 4 2.1 Countervailing Power of Airlines 4 2.2 Negotiate and Arbitrate 6 2.3 Government Funding for Regional Airports 8 2.4 WA Financial Template 9 3 IMPACT OF AIRPORT CHARGES ON REGIONAL AVIATION 10 4 CAPITAL CITY AIRPORTS 11 4.1 Regional Access Arrangements for Sydney Airport 11 4.1.1 Draft Recommendation 7.1 Regional Access to and from Sydney Airport 11 4.1.2 Draft Recommendation 7.2 Commercial Negotiations for NSW Regional Services 11 4.1.3 Draft Recommendation 7.3 Reviewing Sydney Airports Slot Management Scheme 12 5 WESTERN SYDNEY AIRPORT 13 6 THE PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION HAD INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE 13 2 | Page Regional Express (Rex) Response to the Productivity Commission Draft Report on the Economic Regulation of Airports 1 Opening Statement Regional Express (Rex) is responding to the Productivity Commission Draft Report on the Economic Regulation of Airports. Rex will also attend the public hearing and make a verbal response. Overall Rex is very disappointed with the draft report. The draft report is full of errors and incorrect assumptions. We are surprised that the Productivity Commission (the Commission) has chosen to ignore the evidence and arguments put forward by airlines whilst willingly accepting evidence and arguments put forward by the airports. It appears that either the Commission did not read Rex’s submission, totalling about 500 pages, or if it did, decided to ignore it. -

Regional Express Holdings Limited Was Listed on the ASX in 2005

Productivity Commission Inquiry Submission by Regional Express Contents: Section 1: Background about Regional Express Section 2: High Level Response to the Fundamental Question. Sections 3 – 6: Evidence of Specific Issues with respect to Sydney Airport. Section 7: Response to the ACCC Deemed Declaration Proposal for Sydney Airport Section 8: Other Airports and Positive Examples Section 9: Conclusions 1. Background about Regional Express 1.1. Regional Express was formed in 2002 out of the collapse of the Ansett group, which included the regional operators Hazelton and Kendell, in response to concerns about the economic impact on regional communities dependent on regular public transport air services previously provided by Hazelton and Kendell. 1.2. Regional Express Holdings Limited was listed on the ASX in 2005. The subsidiaries of Regional Express are: • Regional Express Pty Limited ( Rex ), the largest independent regional airline in Australia and the largest independent regional airline operating at Sydney airport; • Air Link Pty Limited, which provides passenger charter services and based in Dubbo NSW, • Pel-Air Aviation Pty Limited, whose operations cover specialist charter, defence, medivac and freight operations; and • the Australian Airline Pilot Academy Pty Limited (AAPA ) which provides airline pilot training and the Rex pilot cadet programme. 1.3. Rex has regularly won customer service awards for its regional air services and in February 2010, Rex was awarded “Regional Airline of the Year 2010” by Air Transport World. This is only the second time that an Australian regional airline has won this prestigious international award, the previous occasion being in 1991 when this award was won by Kendell. -

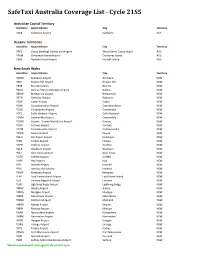

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

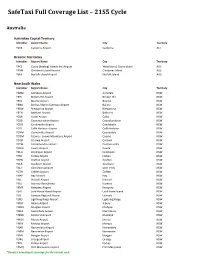

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

Cabin Crew) Pre-Course Information and Learning

14 COMPASS ROAD, JANDAKOT PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING IF YOU HAVE RECEIVED AN OFFER FOR THE FOLLOWING COURSE National ID: AVI30219 Course: AZS9 Certificate III in Aviation (Cabin Crew) Pre-Course Information and Learning Course Outline: The Certificate III in Aviation (Cabin Crew) course requires you to be able to work effectively in a team environment as part of a flight crew, work on board a Boeing 737 in the aircraft cabin and perform first aid in an aviation environment. Part of your training will require you to be able to swim fully clothed to conduct emergency procedures in a raft. Self-defence skills are taught as part of the curriculum which may require you to be in close proximity to the trainees. When you complete the Certificate III in Aviation (Cabin Crew) you will be recruitment-ready for an exciting career as a flight attendant or cabin crew member. You will gain valuable experience and skills in emergency response drills, first aid, responsible service of alcohol, teamwork and customer service, and preparation for cabin duties. You will gain confidence in dealing with difficult passengers on an aircraft with crew member security training. This course is specifically designed for those seeking an exciting career as a cabin crew member (flight attendant). This course has been developed in conjunction with commercial airlines and experienced cabin crew training managers to meet current aviation standards and will thoroughly prepare you to be successful in the airline industry. South Metropolitan TAFE has a Boeing 737 which will be used for the majority of your practical training. -

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze Zestawienie Zawiera 8372 Kody Lotnisk

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze zestawienie zawiera 8372 kody lotnisk. Zestawienie uszeregowano: Kod ICAO = Nazwa portu lotniczego = Lokalizacja portu lotniczego AGAF=Afutara Airport=Afutara AGAR=Ulawa Airport=Arona, Ulawa Island AGAT=Uru Harbour=Atoifi, Malaita AGBA=Barakoma Airport=Barakoma AGBT=Batuna Airport=Batuna AGEV=Geva Airport=Geva AGGA=Auki Airport=Auki AGGB=Bellona/Anua Airport=Bellona/Anua AGGC=Choiseul Bay Airport=Choiseul Bay, Taro Island AGGD=Mbambanakira Airport=Mbambanakira AGGE=Balalae Airport=Shortland Island AGGF=Fera/Maringe Airport=Fera Island, Santa Isabel Island AGGG=Honiara FIR=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGH=Honiara International Airport=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGI=Babanakira Airport=Babanakira AGGJ=Avu Avu Airport=Avu Avu AGGK=Kirakira Airport=Kirakira AGGL=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova Airport=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova, Santa Cruz Island AGGM=Munda Airport=Munda, New Georgia Island AGGN=Nusatupe Airport=Gizo Island AGGO=Mono Airport=Mono Island AGGP=Marau Sound Airport=Marau Sound AGGQ=Ontong Java Airport=Ontong Java AGGR=Rennell/Tingoa Airport=Rennell/Tingoa, Rennell Island AGGS=Seghe Airport=Seghe AGGT=Santa Anna Airport=Santa Anna AGGU=Marau Airport=Marau AGGV=Suavanao Airport=Suavanao AGGY=Yandina Airport=Yandina AGIN=Isuna Heliport=Isuna AGKG=Kaghau Airport=Kaghau AGKU=Kukudu Airport=Kukudu AGOK=Gatokae Aerodrome=Gatokae AGRC=Ringi Cove Airport=Ringi Cove AGRM=Ramata Airport=Ramata ANYN=Nauru International Airport=Yaren (ICAO code formerly ANAU) AYBK=Buka Airport=Buka AYCH=Chimbu Airport=Kundiawa AYDU=Daru Airport=Daru -

Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects

Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects 1 COPYRIGHT DISCLAIMER Restart NSW Local and Community While every reasonable effort has been made Infrastructure Projects to ensure that this document is correct at the time of publication, Infrastructure NSW, its © July 2019 State of New South Wales agents and employees, disclaim any liability to through Infrastructure NSW any person in response of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted to This document was prepared by Infrastructure be done in reliance upon the whole or any part NSW. It contains information, data and images of this document. Please also note that (‘material’) prepared by Infrastructure NSW. material may change without notice and you should use the current material from the The material is subject to copyright under Infrastructure NSW website and not rely the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), and is owned on material previously printed or stored by by the State of New South Wales through you. Infrastructure NSW. For enquiries please contact [email protected] This material may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial Front cover image: Armidale Regional use, providing the meaning is unchanged and Airport, Regional Tourism Infrastructure its source, publisher and authorship are clearly Fund and correctly acknowledged. 2 Restart NSW Local and Community Infrastructure Projects The Restart NSW Fund was established by This booklet reports on local and community the NSW Government in 2011 to improve infrastructure projects in regional NSW, the economic growth and productivity of Newcastle and Wollongong. The majority of the state. -

NSW Service Level Specification

Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory – Version 3.13 Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory This document outlines the Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services provided by the Commonwealth of Australia through the Bureau of Meteorology for the State of New South Wales in consultation with the New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory Flood Warning Consultative Committee. Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for New South Wales Published by the Bureau of Meteorology GPO Box 1289 Melbourne VIC 3001 (03) 9669 4000 www.bom.gov.au With the exception of logos, this guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Australia Attribution Licence. The terms and conditions of the licence are at www.creativecommons.org.au © Commonwealth of Australia (Bureau of Meteorology) 2013. Cover image: Major flooding on the Hunter River at Morpeth Bridge in June 2007. Photo courtesy of New South Wales State Emergency Service Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory Table of Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 2 Flood Warning Consultative Committee .......................................................................... 4 -

List of Airports in Australia - Wikipedia

List of airports in Australia - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_airports_in_Australia List of airports in Australia This is a list of airports in Australia . It includes licensed airports, with the exception of private airports. Aerodromes here are listed with their 4-letter ICAO code, and 3-letter IATA code (where available). A more extensive list can be found in the En Route Supplement Australia (ERSA), available online from the Airservices Australia [1] web site and in the individual lists for each state or territory. Contents 1 Airports 1.1 Australian Capital Territory (ACT) 1.2 New South Wales (NSW) 1.3 Northern Territory (NT) 1.4 Queensland (QLD) 1.5 South Australia (SA) 1.6 Tasmania (TAS) 1.7 Victoria (VIC) 1.8 Western Australia (WA) 1.9 Other territories 1.10 Military: Air Force 1.11 Military: Army Aviation 1.12 Military: Naval Aviation 2 See also 3 References 4 Other sources Airports ICAO location indicators link to the Aeronautical Information Publication Enroute Supplement – Australia (ERSA) facilities (FAC) document, where available. Airport names shown in bold indicate the airport has scheduled passenger service on commercial airlines. Australian Capital Territory (ACT) City ICAO IATA Airport name served/location YSCB (https://www.airservicesaustralia.com/aip/current Canberra Canberra CBR /ersa/FAC_YSCB_17-Aug-2017.pdf) International Airport 1 of 32 11/28/2017 8:06 AM List of airports in Australia - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_airports_in_Australia New South Wales (NSW) City ICAO IATA Airport -

Avis Australia & New Zealand Offer 2019

Australia Australian Capital Territory Location Name Address Suburb Postcode Canberra 51-53 Mort St, Unit 236 Braddon 2601 Canberra 25 Tennant St, Unit 2 Fyshwick 2609 Canberra Airport 25 Terminal Ave Canberra Airport 2609 Fyshwick 25 Tennant Street, Unit 2 Fyshwick 2609 New South Wales Location Name Address Suburb Postcode Circular Quay 30 Pitt Street, Sydney Harbour Marriott Circular Quay 2000 World Square 395 Pitt Street Sydney 2000 The Star Casino 55 Pirrama Rd Pyrmont 2009 Sydney Kings Cross 200 William Street Kings Cross 2011 Alexandria 944 Bourke St Waterloo 2017 Sydney Airport Terminals 1, 2 & 3 Mascot 2020 Bondi Junction 204 Oxford St Bondi Junction 2022 North Sydney Level 7 Northpoint Tower, 100 Miller St North Sydney 2060 Artarmon 75-77 Carlotta Street Artarmon 2064 Hornsby 126 Pacific Highway Hornsby 2077 Dee Why 814 Pittwater Road Dee Why 2099 West Ryde 899 Victoria Road West Ryde 2114 Croydon 142 Parramatta Rd Croydon 2132 North Parramatta 610-614 Church Street North Parramatta 2150 Castle Hill 4 Victoria Avenue Castle Hill 2154 Hurstville 737-739 Forest Rd Bexley 2207 Bankstown 112 Milperra Rd Revesby 2212 Hurstville 737-739 Forest Road Hurstville 2220 Taren Point 114 Taren Point Road Taren Point 2229 Gosford 322 Mann Street Gosford 2250 Newcastle 50 Clyde St Hamilton North 2292 Newcastle Airport Williamtown Dr Williamtown 2318 Tamworth 1 Wilkinson Street Tamworth 2340 Tamworth Airport Basil Brown Drive Tamworth 2340 Armidale 32 Saumarez Rd Armidale 2350 Armidale Airport 9 Peter Monley Drive Armidale 2350 Armidale Downtown 32 Saumarez Rd Armidale 2350 Narrabri Airport 307 Airport Rd Narrabri 2390 Moree 102 Balo Street Moree 2400 Moree Airport Newell Hwy Moree 2400 Moree Downtown 305 Frome St Moree 2400 Port Macquarie 99 Boundary Street Port Macquarie 2444 Airport Coffs Harbour 22 Park Avenue, Shop 2 Coffs Harbour 2450 Coffs Harbour Airport Airport Dr Coffs Harbour 2450 Page 1 of 8 12 Shelley Street, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia. -

Location After Hours Drop Location After Hours Drop

Location After hours drop Location After hours drop QLD Port Douglas YES Townsville NO Cairns Airport YES Mackay NO Cairns City YES Maryborough NO Brisbane Airport YES Brisbane City NO Weipa YES- drop off box in Arrivals Terminal Townsville Airport YES - key return on counter Mackay Airport YES- key return on counter Rockhampton YES – on the side of the wash bay Rockhampton Airport YES – at the kiosk desk Gladstone Airport YES – at the kiosk desk Bundaberg YES – front door Bundaberg Airport YES– at the kiosk desk Hervey Bay YES- front door Hervey Bay Airport YES – at the kiosk desk Emerald YES – side front door Emerald Airport YES – at the kiosk desk NSW Newcastle Airport YES- drop box at the terminal Gunnedah NO Brookvale YES Griffith Airport NO Sydney Airport YES Narrabri NO YES- drop box on the west side of the Alexandria Narrabri Airport NO building 1 NO - afterhours Griffith City YES Port Macquarie City provision, case by case Armidale YES Hornsby NO Armidale Airport YES Artarmon NO Moree YES Sydney City NO Moree Airport YES Sydney Darlinghurst NO Tamworth YES Wynyard NO Tamworth Airport YES Dubbo YES Mudgee YES Bathurst YES Lithgow YES Parkes City YES Broken Hill YES Broken Hill APT YES Mildura YES Grafton City YES Grafton Airport YES Coffs Harbour City YES Coffs Harbour APT YES YES - north side of building (not main Taree APT terminal doors) + keyhole at thrifty desk Port Macquarie APT YES ACT Canberra Airport YES - In Terminal on desk Canberra City NO Canberra City NO VIC 2 Melbourne Airport YES Melbourne City NO Melbourne Airport -

Budget Estimates 2006-2007 — (May 2006)

Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE Budget Estimates May 2006 Transport and Regional Services Question No: OTS 01 Division/Agency: Office of Transport Security Topic: Non-Australian Licensed Vessel Permits Hansard Page: 53 (23/05/06) Senator O’Brien asked: Senator O’BRIEN—Does anyone check with them to see that they are actually inquiring whether the permit states the type of cargo that was actually carried? Mr Tongue—We will have to take that one on notice. Answer: Permits holders are required to provide a Statement of Cargo Actually Carried within 14 days of the sailing date. The Department of Transport and Regional Services advises Customs when a vessel is issued with either a Single or Continuing Voyage Permit (SVP or CVP). The Master or operator of these vessels must apply to Customs for a clearance from each port in Australia whether on a direct departing voyage to a place outside Australia, or to an intermediate voyage to another port within Australia. There is a requirement for domestic cargo to be reported to Customs via the Integrated Cargo System (ICS), however, the information reported through the ICS does not allow for a detailed reconciliation. The Master of the vessel (or its agent) must produce to Customs a copy of the SVP or CVP whenever domestic cargo is to be uploaded or discharged. Customs officers examine the document to ensure that it is valid for the voyage involved. Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE Budget Estimates May 2006 Transport and Regional Services Question No: OTS 02 Division/Agency: Office of Transport Security Topic: Unattended Baggage Hansard Page: 58 (23/05/06) Senator O’Brien asked: Senator O’BRIEN—How many people have been charged for leaving baggage unattended so far? Mr Windeyer—I would have to take that on notice Answer: We are unaware of any persons being charged yet.