Writing Wounded: Trauma, Testimony, and Critical Witness in Literacy Classrooms Extending the Conversation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This One, with Gratitude, Is for DON CONGDON

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book-paper catches fire and burns PART I: THE HEARTH AND THE SALAMANDER IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN. IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon- winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at himself, a minstrel man, Does% burntcorked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his Montag% face muscles, in the dark. -

Gaslightpdffinal.Pdf

Credits. Book Layout and Design: Miah Jeffra Cover Artwork: Pseudodocumentation: Broken Glass by David DiMichele, Courtesy of Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco ISBN: 978-0-692-33821-6 The Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBTQ Voices is made possible, in part, by a generous contribution by Amazon.com Gaslight Vol. 1 No. 1 2014 Gaslight is published once yearly in Los Angeles, California Gaslight is exclusively a publication of recipients of the Lambda Literary Foundation's Emerging Voices Fellowship. All correspondence may be addressed to 5482 Wilshire Boulevard #1595 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Details at www.lambdaliterary.org. Contents Director's Note . 9 Editor's Note . 11 Lisa Galloway / Epitaph ..................................13 / Hives ....................................16 Jane Blunschi / Snapdragon ................................18 Miah Jeffra / Coffee Spilled ................................31 Victor Vazquez / Keiki ....................................35 Christina Quintana / A Slip of Moon ........................36 Morgan M Page / Cruelty .................................51 Wayne Johns / Where Your Children Are ......................53 Wo Chan / Our Majesties at Michael's Craft Shop ..............66 / [and I, thirty thousand feet in the air, pop] ...........67 / Sonnet by Lamplight ............................68 Yana Calou / Mortars ....................................69 Hope Thompson/ Sharp in the Dark .........................74 Yuska Lutfi Tuanakotta / Mother and Son Go Shopping ..........82 Megan McHugh / I Don't Need to Talk -

King's Speech

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION 2010 BEST ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY David Seidler THE KING'S SPEECH Screenplay by David Seidler See-Saw Films/Bedlam Productions CARD: 1925 King George V reigns over a quarter of the world’s population. He asks his second son, the Duke of York, to give the closing speech at the Empire Exhibition in Wembley, London. INT. BBC BROADCASTING HOUSE, STUDIO - DAY CLOSE ON a BBC microphone of the 1920's, A formidable piece of machinery suspended on springs. A BBC NEWS READER, in a tuxedo with carnation boutonniere, is gargling while a TECHNICIAN holds a porcelain bowl and a towel at the ready. The man in the tuxedo expectorates discreetly into the bowl, wipes his mouth fastidiously, and signals to ANOTHER TECHNICIAN who produces an atomizer. The Reader opens his mouth, squeezes the rubber bulb, and sprays his inner throat. Now, he’s ready. The reader speaks in flawless pear-shaped tones. There’s no higher creature in the vocal world. BBC NEWS READER Good afternoon. This is the BBC National Programme and Empire Services taking you to Wembley Stadium for the Closing Ceremony of the Second and Final Season of the Empire Exhibition. INT. CORRIDOR, WEMBLEY STADIUM - DAY CLOSE ON a man's hand clutching a woman's hand. Woman’s mouth whispers into man's ear. BBC NEWS READER (V.O.) 58 British Colonies and Dominions have taken part, making this the largest Exhibition staged anywhere in the world. Complete with the new stadium, the Exhibition was built in Wembley, Middlesex at a cost of over 12 million pounds. -

The Construction and Export of African American Images in Hip-Hop Culture

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2006 "Don't Believe the Hype": The onsC truction and Export of African American Images in Hip-Hop Culture. John Ike Sewell Jr. East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Sewell, John Ike Jr., ""Don't Believe the Hype": The onC struction and Export of African American Images in Hip-Hop Culture." (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2193. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2193 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Don’t Believe The Hype”: The Construction and Export of African American Images in Hip-Hop Culture ____________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Communication East Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Professional Communication ____________ by John Ike Sewell, Jr. May 2006 ____________ Amber Kinser, Ph.D., Chair Primus Tillman, Ph.D. John Morefield, Ph.D. ____________ Keywords: Hip-hop, Rap Music, Imagery, Blackness, Archetype ABSTRACT “Don’t Believe the Hype:” The Construction and Export of African American Images in Hip-Hop Culture by John Ike Sewell, Jr. -

The Last Days of John Lennon

Copyright © 2020 by James Patterson Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 littlebrown.com twitter.com/littlebrown facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany First ebook edition: December 2020 Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. ISBN 978-0-316-42907-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945289 E3-111020-DA-ORI Table of Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Prologue Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 — Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 — Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 -

Please Take Me with You

3,149 words Please Take Me with You “Good God, it REEKS!” The shrill voice cut through the silence which permeated the cramped quarters of our Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicle. “Smells like money to me, Doc,” the reply floated down to us through the roof-mounted turret. “I’m in the wrong business!” “I can’t believe they let you have a gun, McCloud,” Sergeant Strauss snapped, removing her glasses to wipe watery eyes with the edge of a worn, digital-patterned sleeve. It did reek. The sour, pungent smell of marijuana poured through the open turret and sliced through the familiar stink of sweat-soaked leather and motor oil, assaulting our noses. We’d been on the road for over an hour, heading to a small combat outpost on the outskirts of the Arghandab River Valley district of Kandahar Province to drop supplies or provide security or clear the roads—I don’t remember the ‘whys’ now; I’m not sure I ever knew them in the first place—I only remember the ‘whos.’ The banter continued, a distant buzz while I squinted through inches of foggy, ballistic glass at the world outside. This was my first time leaving the outpost, my first glimpse of Afghanistan that wasn’t skewed by barbed wire or distanced by the bird’s eye view from a guard tower. It didn’t look like the Afghanistan I’d seen on CNN at all. It’s so green, I thought to myself, remembering the footage I’d seen of a UH-6 Black Hawk helicopter flying over Kandahar, the city a maze of muddy walls and more shades of brown than I’d ever known existed. -

Fahrenheit 451

1 FAHRENHEIT 451 By Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book-paper catches fire and burns PART I IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon-winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at himself, a minstrel man, burnt-corked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his face muscles, in the dark. -

Homeless Mutant Quest 26-50.Docx

HOMELESS MUTANT QUEST Threads 26-50 By Crusty Jones X-men was created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby and are owned by Marvel (pls don’t sue him Mickey) Thread #26 Thread #27 Thread #28 Thread #29 Thread #30 Thread #31 Thread #32 Thread #33 Thread #34 Thread #35 Thread #36 Thread #37 Thread #38 Thread #39 Thread #40 Thread #41 Thread #42 Thread #43 Thread #44 Thread #45 Thread #46 Thread #47 Thread #48 Thread #49 Thread #50 Thread #26 As the evening descends, so do the birds. You pick your way through the scar in silence, Gabriella ambling just about alongside you, her breath staggering noisily as she flinches and shuffles and cringes her way over the snow. Laura is hanging back somewhat – whenever you slow down, you can’t quite seem to pull her closer, her pace shifting to accommodate, keeping her orbiting at a fair distance. Occasionally you’re sure you can feel her eyes boring into your back. But you can feel everyone’s eyes doing that – it’s just who you are. The scar is easy nesting. When the sun dims, the pigeons and the crows and the other tiny, winged shapes you couldn’t put a name to crowd in, their collective rustling and preening rising as a sort of low, reverent applause, clapping the day off stage. It edges away and away along the sky until there’s only red, and the thin, withered winter clouds take on the appearance of long wounds. Thinking about the scar is a good distraction. -

Gritting Teeth: a Memoir of Unhealthy Love Samantha L

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 12-2010 Gritting Teeth: A Memoir of Unhealthy Love Samantha L. Day Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Day, Samantha L., "Gritting Teeth: A Memoir of Unhealthy Love" (2010). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 230. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/230 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GRITTING TEETH: A MEMOIR OF UNHEALTHY LOVE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Samantha L. Day December 2010 GRITTING TEETH: A MEMOIR OF UNHEALTHY LOVE Date Recommended Alo V. ;3 ~~(?~ ,I DirecoTOf Thesis ~ P~A.~ )4- '2J.,,~11 Dean, Graduate Studies and Research Date -- ---------i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to my thesis director, Dale Rigby, for his input, encouragement, and mentorship over the past year. I also want to thank my other committee members, David LeNoir and Wes Berry, for their patience and support. I owe my parents, Carol and John Nomikos, a million times over for putting me up when I had nowhere else to go and kicking me in the ass when I was ready to give up. And to April Schofield: Thanks for having faith in my writing and my ability to pull through. -

Early Musicians' Unions in Britain, France, And

Angèle David-Guillou Early musicians' unions in Britain, France, and the United States: on the possibilities and impossibilities of transnational militant transfers in an international industry Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: David-Guillou, Angèle (2009) Early musicians' unions in Britain, France, and the United States: on the possibilities and impossibilities of transnational militant transfers in an international industry. Labour history review, 74 (3). pp. 288-304. DOI: 10.1179/096156509X12513818419655 © 2009 Maney Publishing/ Society for the Study of Labour History This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/30555/ Available in LSE Research Online: April 2011 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Angèle David-Guillou Early musicians’ unions in Britain, France and the United States: on the possibilities and impossibilities of transnational militant transfers in an international industry (short title: Early musicians’ unions) Abstract The end of the nineteenth century marks the beginnings of the popular music industry. -

Th Each Other Us Absolutely Everything

e h t the rretrIeveretrIever UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, BALTIMORE COUNTY’S STUDENT NEWSPAPER wweeklyeekly . 110.30.070.30.07 VOLUME 42 ISSUE 10 retrieverweekly com Poet Jennifer Raising Rose gets domestic realistic violence Ariane Szu-Tu EDITORIAL STAFF awareness Poet Jennifer Rose came to UMBC to discuss, and to read excerpts from, Anne Verghese her latest compilation Hometown for an STAFF WRITER Hour. The selections she chose included “Province Town Postcard,” “Cape Cod Baltimore City resident Katiria Postcard,” and the much-reworked Delacruz’s life was cut short at the “Prospect Street.” Besides being an young age of 24 on Friday, June 9, award-winning poet, Jennifer Rose is 2006, when she was shot. She is one also an urban planner working on revi- among the 63 deaths reported in talizing downtown Baltimore. Maryland since 2005 due to domestic Students and faculty present in the KAT WATERS — TRW violence. This October, in recogni- University Center room on the rainy > Antonio Williams took command of UMBC’s police force in June and stresses the importance of student aware- tion of Domestic Violence Awareness afternoon fell silent as Rose began to ness in reducing the frquency of thefts and burglaries on campus. month, Voices Against Violence (VAV) read aloud. Her poetry, stemming from sponsored several events on campus, a naturalistic point of view, sketched How you can make a safer UMBC such as the Purple Ribbon Campaign, images of a wide range of experiences Awareness Day, the White Sash Proj- from all over the globe. Andrea Thomson and retired as a colonel. -

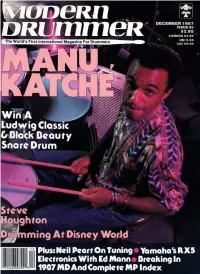

December 1987

VOLUME 11, NUMBER 1 2, ISSUE 98 Cover Photo by Jaeger Kotos EDUCATION IN THE STUDIO Drumheads And Recording Kotos by Craig Krampf 38 SHOW DRUMMERS' SEMINAR Jaeger Get Involved by by Vincent Dee 40 KEYBOARD PERCUSSION Photo In Search Of Time by Dave Samuels 42 THE MACHINE SHOP New Sounds For Your Old Machines by Norman Weinberg 44 ROCK PERSPECTIVES Ringo Starr: The Later Years by Kenny Aronoff 66 ELECTRONIC INSIGHTS Percussive Sound Sources And Synthesis by Ed Mann 68 TAKING CARE OF BUSINESS Breaking In MANU KATCHE by Karen Ervin Pershing 70 One of the highlights of Peter Gabriel's recent So album and ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC tour was French drummer Manu Katche, who has gone on to Two-Surface Riding: Part 2 record with such artists as Sting, Joni Mitchell, and Robbie by Rod Morgenstein 82 Robertson. He tells of his background in France, and explains BASICS why Peter Gabriel is so important to him. Thoughts On Tom Tuning by Connie Fisher 16 by Neil Peart 88 TRACKING DRUMMING AT DISNEY Studio Chart Interpretation by Hank Jaramillo 100 WORLD DRUM SOLOIST When it comes to employment opportunities, you have to Three Solo Intros consider Disney World in Florida, where 45 to 50 drummers by Bobby Cleall 102 are working at any given time. We spoke to several of them JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP about their working conditions and the many styles of music Fast And Slow Tempos that are represented there, by Peter Erskine 104 by Rick Van Horn 22 CONCEPTS Drummers Are Special People STEVE HOUGHTON by Roy Burns 116 He's known for his big band work with Woody Herman, EQUIPMENT small-group playing with Scott Henderson, and his teaching at SHOP TALK P.I.T.