The Evolutionary Transition from Lungs to a Gas Bladder: Evidence from Immunohistochemistry, Rna-Seq, and Morphology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digenetic Trematodes of Marine Teleost Fishes from Biscayne Bay, Florida Robin M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Laboratory of Parasitology 6-26-1969 Digenetic Trematodes of Marine Teleost Fishes from Biscayne Bay, Florida Robin M. Overstreet University of Miami, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Overstreet, Robin M., "Digenetic Trematodes of Marine Teleost Fishes from Biscayne Bay, Florida" (1969). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 867. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/867 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TULANE STUDIES IN ZOOLOGY AND BOTANY Volume 15, Number 4 June 26, 1969 DIGENETIC TREMATODES OF MARINE TELEOST FISHES FROM BISCAYNE BAY, FLORIDA1 ROBIN M. OVERSTREET2 Institute of Marine Sciences, University of Miami, Miami, Florida CONTENTS ABSTRACT 120 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 120 INTRODUCTION -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi

Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 (http://www.accessscience.com/) Article by: Boschung, Herbert Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Gardiner, Brian Linnean Society of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, United Kingdom. Publication year: 2014 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400) Content Morphology Euteleostei Bibliography Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi The most recent group of actinopterygians (rayfin fishes), first appearing in the Upper Triassic (Fig. 1). About 26,840 species are contained within the Teleostei, accounting for more than half of all living vertebrates and over 96% of all living fishes. Teleosts comprise 517 families, of which 69 are extinct, leaving 448 extant families; of these, about 43% have no fossil record. See also: Actinopterygii (/content/actinopterygii/009100); Osteichthyes (/content/osteichthyes/478500) Fig. 1 Cladogram showing the relationships of the extant teleosts with the other extant actinopterygians. (J. S. Nelson, Fishes of the World, 4th ed., Wiley, New York, 2006) 1 of 9 10/7/2015 1:07 PM Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 Morphology Much of the evidence for teleost monophyly (evolving from a common ancestral form) and relationships comes from the caudal skeleton and concomitant acquisition of a homocercal tail (upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin are symmetrical). This type of tail primitively results from an ontogenetic fusion of centra (bodies of vertebrae) and the possession of paired bracing bones located bilaterally along the dorsal region of the caudal skeleton, derived ontogenetically from the neural arches (uroneurals) of the ural (tail) centra. -

Vertebrate Proteins Predicted from Genomic Sequences

Vertebrate proteins predicted from genomic sequences VWD C8 TIL PTS Mucin2_WxxW F5_F8_type_C FCGBP_N VWC Lethenteron_camtschaticum Cyclostomata; Hyperoartia; Petromyzontiformes; Petromyzontidae; Lethenteron Lethenteron_camtschaticum.0.pep1 Petromyzon_marinus Cyclostomata; Hyperoartia; Petromyzontiformes; Petromyzontidae; Petromyzon Petromyzon_marinus.0.pep1 Callorhinchus_milii Gnathostomata; Chondrichthyes; Holocephali; Chimaeriformes; Callorhinchidae; Callorhinchus Callorhinchus_milii.0.pep1 Callorhinchus_milii Gnathostomata; Chondrichthyes; Holocephali; Chimaeriformes; Callorhinchidae; Callorhinchus Callorhinchus_milii.0.pep2 Callorhinchus_milii Gnathostomata; Chondrichthyes; Holocephali; Chimaeriformes; Callorhinchidae; Callorhinchus Callorhinchus_milii.0.pep3 Lepisosteus_oculatus Gnathostomata; Teleostomi; Euteleostomi; Actinopterygii; Actinopteri; Neopterygii; Holostei; Semionotiformes; Lepisosteus_oculatus.0.pep1 Lepisosteus_oculatus Gnathostomata; Teleostomi; Euteleostomi; Actinopterygii; Actinopteri; Neopterygii; Holostei; Semionotiformes; Lepisosteus_oculatus.0.pep2 Lepisosteus_oculatus Gnathostomata; Teleostomi; Euteleostomi; Actinopterygii; Actinopteri; Neopterygii; Holostei; Semionotiformes; Lepisosteus_oculatus.0.pep3 Lepisosteus_oculatus Gnathostomata; Teleostomi; Euteleostomi; Actinopterygii; Actinopteri; Neopterygii; Holostei; Semionotiformes; Lepisosteus_oculatus.1.pep1 TILa Cynoglossus_semilaevis Gnathostomata; Teleostomi; Euteleostomi; Actinopterygii; Actinopteri; Neopterygii; Teleostei; Cynoglossus_semilaevis.1.pep1 -

The Evolution of the Placenta Drives a Shift in Sexual Selection in Livebearing Fish

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature13451 The evolution of the placenta drives a shift in sexual selection in livebearing fish B. J. A. Pollux1,2, R. W. Meredith1,3, M. S. Springer1, T. Garland1 & D. N. Reznick1 The evolution of the placenta from a non-placental ancestor causes a species produce large, ‘costly’ (that is, fully provisioned) eggs5,6, gaining shift of maternal investment from pre- to post-fertilization, creating most reproductive benefits by carefully selecting suitable mates based a venue for parent–offspring conflicts during pregnancy1–4. Theory on phenotype or behaviour2. These females, however, run the risk of mat- predicts that the rise of these conflicts should drive a shift from a ing with genetically inferior (for example, closely related or dishonestly reliance on pre-copulatory female mate choice to polyandry in conjunc- signalling) males, because genetically incompatible males are generally tion with post-zygotic mechanisms of sexual selection2. This hypoth- not discernable at the phenotypic level10. Placental females may reduce esis has not yet been empirically tested. Here we apply comparative these risks by producing tiny, inexpensive eggs and creating large mixed- methods to test a key prediction of this hypothesis, which is that the paternity litters by mating with multiple males. They may then rely on evolution of placentation is associated with reduced pre-copulatory the expression of the paternal genomes to induce differential patterns of female mate choice. We exploit a unique quality of the livebearing fish post-zygotic maternal investment among the embryos and, in extreme family Poeciliidae: placentas have repeatedly evolved or been lost, cases, divert resources from genetically defective (incompatible) to viable creating diversity among closely related lineages in the presence or embryos1–4,6,11. -

Tennessee Fish Species

The Angler’s Guide To TennesseeIncluding Aquatic Nuisance SpeciesFish Published by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Cover photograph Paul Shaw Graphics Designer Raleigh Holtam Thanks to the TWRA Fisheries Staff for their review and contributions to this publication. Special thanks to those that provided pictures for use in this publication. Partial funding of this publication was provided by a grant from the United States Fish & Wildlife Service through the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Authorization No. 328898, 58,500 copies, January, 2012. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $.42 per copy. Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency is available to all persons without regard to their race, color, national origin, sex, age, dis- ability, or military service. TWRA is also an equal opportunity/equal access employer. Questions should be directed to TWRA, Human Resources Office, P.O. Box 40747, Nashville, TN 37204, (615) 781-6594 (TDD 781-6691), or to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office for Human Resources, 4401 N. Fairfax Dr., Arlington, VA 22203. Contents Introduction ...............................................................................1 About Fish ..................................................................................2 Black Bass ...................................................................................3 Crappie ........................................................................................7 -

Bowfin (Amia Calva)

Indiana Division of Fish and Wildlife’s Animal Information Series Bowfin (Amia calva) Do they have any other names? Other names for the bowfin are dogfish, grindle, grinnel, cypress trout, swamp muskie, black fish, cottonfish, swamp bass, poisson-castor, speckled cat, shoepic or choupic, and beaverfish. Why are they called bowfin? Amia is Greek for “fish” and calva is Greek for “bald or smooth” which refers to the bowfin’s scaleless head. The name “bowfin” refers to the long curved fin on the back of the fish. What do they look like? The bowfin is an elongate and nearly-cylindrical fish with a long dorsal (back) fin that extends from the middle of the back to the tail. The tail fin is rounded and has a black spot on the upper base of the tail. This black spot resembles an eye that predators will mistakenly attack, allowing the bowfin to get away. The back and tail fins are dark- green with darker bands or bars and the lower fins are bright green. The back and upper sides are mottled olive-green with pale green on the belly. The head is without scales but the body is covered in smooth-edged scales. They also have a large mouth with many sharp teeth and each nostril has a prominent barbel-like flap. Photo Credit: Duane Raver, USFWS 2012-MLC Page 1 Bowfin vs. Snakehead Bowfins are often mistaken as snakeheads, which are an exotic fish species native to Africa and Asia. Snakeheads are an aggressive invasive species that have little to no predators outside their native waters. -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

Constraints on the Timescale of Animal Evolutionary History

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history Michael J. Benton, Philip C.J. Donoghue, Robert J. Asher, Matt Friedman, Thomas J. Near, and Jakob Vinther ABSTRACT Dating the tree of life is a core endeavor in evolutionary biology. Rates of evolution are fundamental to nearly every evolutionary model and process. Rates need dates. There is much debate on the most appropriate and reasonable ways in which to date the tree of life, and recent work has highlighted some confusions and complexities that can be avoided. Whether phylogenetic trees are dated after they have been estab- lished, or as part of the process of tree finding, practitioners need to know which cali- brations to use. We emphasize the importance of identifying crown (not stem) fossils, levels of confidence in their attribution to the crown, current chronostratigraphic preci- sion, the primacy of the host geological formation and asymmetric confidence intervals. Here we present calibrations for 88 key nodes across the phylogeny of animals, rang- ing from the root of Metazoa to the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens. Close attention to detail is constantly required: for example, the classic bird-mammal date (base of crown Amniota) has often been given as 310-315 Ma; the 2014 international time scale indicates a minimum age of 318 Ma. Michael J. Benton. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Philip C.J. Donoghue. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Robert J. -

Four New Records of Fish Species (Cypriniformes: Nemacheilidae

Zoological Research 35 (1): 51−58 DOI:10.11813/j.issn.0254-5853.2014.1.051 Four new records of fish species (Cypriniformes: Nemacheilidae, Balitoridae; Characiformes: Prochilodontidae) and corrections of two misidentified fish species (Tetraodontiformes: Tetraodontidae; Beloniformes: Belonidae) in Yunnan, China Marco Endruweit* Qingshan Road 601, Qingdao, China Abstract: In this study, six fish species of five families are reported for the first time from Yunnan Province, China. The nemacheilid Schistura amplizona Kottelat, 2000 is reported from the Luosuojiang River and Nanlahe River subbasins, Mekong basin; the prochilodontid Prochilodus lineatus (Valenciennes, 1837), the balitorid Vanmanenia serrilineata Kottelat, 2000, and the tetraodontid Monotrete turgidus Kottelat, 2000, from Nanlahe River subbasin, Mekong basin; the balitorid Beaufortia daon (Mai, 1978), and the belonid Xenentodon canciloides (Bleeker, 1854), both, from Black River subbasin, Red River basin. The freshwater puffer M. turgidus and the needlefish X. canciloides have been previously misidentified as Tetraodon leiurus (Bleeker, 1950) and Tylosurus strongylurus (van Hasselt, 1823), respectively. Keywords: New record; Misidentification; Mekong basin; Red River; Yunnan Yunnan Province is located in the Southwest within Chen et al in 1989, respectively 1990 for the second the People’s Republic of China. Its name refers to its volume, giving 226 species and subspecies accounts in location south of the Yunling Mountain range. It shares the first volume plus an additional 173 in the second. international border with Myanmar in the West and Through extensive fieldwork and re-evaluation of Southwest, with Laos and Vietnam in the South; national institutionally stored lots the number of Yunnanese fish borders with Xizang Autonomous Region to the species is growing (for e.g. -

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

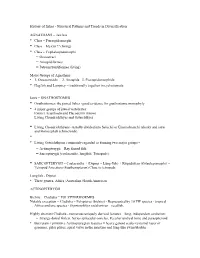

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

Recycled Fish Sculpture (.PDF)

Recycled Fish Sculpture Name:__________ Fish: are a paraphyletic group of organisms that consist of all gill-bearing aquatic vertebrate animals that lack limbs with digits. At 32,000 species, fish exhibit greater species diversity than any other group of vertebrates. Sculpture: is three-dimensional artwork created by shaping or combining hard materials—typically stone such as marble—or metal, glass, or wood. Softer ("plastic") materials can also be used, such as clay, textiles, plastics, polymers and softer metals. They may be assembled such as by welding or gluing or by firing, molded or cast. Researched Photo Source: Alaskan Rainbow STEP ONE: CHOOSE one fish from the attached Fish Names list. Trout STEP TWO: RESEARCH on-line and complete the attached K/U Fish Research Sheet. STEP THREE: DRAW 3 conceptual sketches with colour pencil crayons of possible visual images that represent your researched fish. STEP FOUR: Once your fish designs are approved by the teacher, DRAW a representational outline of your fish on the 18 x24 and then add VALUE and COLOUR . CONSIDER: Individual shapes and forms for the various parts you will cut out of recycled pop aluminum cans (such as individual scales, gills, fins etc.) STEP FIVE: CUT OUT using scissors the various individual sections of your chosen fish from recycled pop aluminum cans. OVERLAY them on top of your 18 x 24 Representational Outline 18 x 24 Drawing representational drawing to judge the shape and size of each piece. STEP SIX: Once you have cut out all your shapes and forms, GLUE the various pieces together with a glue gun. -

Fishes of the Lemon Bay Estuary and a Comparison of Fish Community Structure to Nearby Estuaries Along Florida’S Gulf Coast

Biological Sciences Fishes of the Lemon Bay estuary and a comparison of fish community structure to nearby estuaries along Florida’s Gulf coast Charles F. Idelberger(1), Philip W. Stevens(2), and Eric Weather(2) (1)Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Charlotte Harbor Field Laboratory, 585 Prineville Street, Port Charlotte, Florida 33954 (2)Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, 100 Eighth Avenue Southeast, Saint Petersburg, Florida 33701 Abstract Lemon Bay is a narrow, shallow estuary in southwest Florida. Although its fish fauna has been studied intermittently since the 1880s, no detailed inventory has been available. We sampled fish and selected macroinvertebrates in the bay and lower portions of its tributaries from June 2009 through April 2010 using seines and trawls. One hundred three fish and six invertebrate taxa were collected. Pinfish Lagodon rhomboides, spot Leiostomus xanthurus, bay anchovy Anchoa mitchilli, mojarras Eucinostomus spp., silver perch Bairdiella chrysoura, and scaled sardine Harengula jaguana were among the most abundant species. To place our information into a broader ecological context, we compared the Lemon Bay fish assemblages with those of nearby estuaries. Multivariate analyses revealed that fish assemblages of Lemon and Sarasota bays differed from those of lower Charlotte Harbor and lower Tampa Bay at similarities of 68–75%, depending on collection gear. These differences were attributed to greater abundances of small-bodied fishes in Lemon and Sarasota bays than in the other much larger estuaries. Factors such as water circulation patterns, length of shoreline relative to area of open water, and proximity of Gulf passes to juvenile habitat may differ sufficiently between the small and large estuaries to affect fish assemblages.