David Fallows Lnfluences on Josquin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

Unicode Request for Cyrillic Modifier Letters Superscript Modifiers

Unicode request for Cyrillic modifier letters L2/21-107 Kirk Miller, [email protected] 2021 June 07 This is a request for spacing superscript and subscript Cyrillic characters. It has been favorably reviewed by Sebastian Kempgen (University of Bamberg) and others at the Commission for Computer Supported Processing of Medieval Slavonic Manuscripts and Early Printed Books. Cyrillic-based phonetic transcription uses superscript modifier letters in a manner analogous to the IPA. This convention is widespread, found in both academic publication and standard dictionaries. Transcription of pronunciations into Cyrillic is the norm for monolingual dictionaries, and Cyrillic rather than IPA is often found in linguistic descriptions as well, as seen in the illustrations below for Slavic dialectology, Yugur (Yellow Uyghur) and Evenki. The Great Russian Encyclopedia states that Cyrillic notation is more common in Russian studies than is IPA (‘Transkripcija’, Bol’šaja rossijskaja ènciplopedija, Russian Ministry of Culture, 2005–2019). Unicode currently encodes only three modifier Cyrillic letters: U+A69C ⟨ꚜ⟩ and U+A69D ⟨ꚝ⟩, intended for descriptions of Baltic languages in Latin script but ubiquitous for Slavic languages in Cyrillic script, and U+1D78 ⟨ᵸ⟩, used for nasalized vowels, for example in descriptions of Chechen. The requested spacing modifier letters cannot be substituted by the encoded combining diacritics because (a) some authors contrast them, and (b) they themselves need to be able to take combining diacritics, including diacritics that go under the modifier letter, as in ⟨ᶟ̭̈⟩BA . (See next section and e.g. Figure 18. ) In addition, some linguists make a distinction between spacing superscript letters, used for phonetic detail as in the IPA tradition, and spacing subscript letters, used to denote phonological concepts such as archiphonemes. -

BH Program FINAL

MUSIC BEFORE 1800 Louise Basbas, Director Blue Heron Christmas at the Courts of 15th-Century France & Burgundy Scott Metcalfe, director and harp Jennifer Ashe, Pamela Dellal, Martin Near, Daniela Tosic Michael Barrett, Owen McIntosh, Jason McStoots, Stefan Reed, Mark Sprinkle, Sumner Tompson Cameron Beauchamp, Paul Guttry Laura Jeppesen, vielle and rebec; Charles Weaver, lute and voice Advent O clavis David (O-antiphon for December 20) plainchant Factor orbis Jacob Obrecht (1457/8 - 1505) O virgo virginum (O-antiphon for December 24) plainchant O virgo virginum Josquin Desprez (c. 1455 - 1521) Conditor alme siderum (alternatim hymn for Advent) Guillaume Du Fay (c. 1397 - 1474) Ave Maria gratia dei plena Antoine Brumel (c. 1460 - c. 1512) Christmas O admirabile commercium / Verbum caro factum est Johannes Regis (c. 1425 - 1426) INTERMISSION Christmas Letabundus (Christmas sequence) Guillaume Du Fay Praeter rerum seriem Adrian Willaert (c. 1490 - 1562 New Year’s Day La plus belle et doulce figure Nicolas Grenon (c. 1380 - 1456) Dieu vous doinst bon jour et demy Guillaume Malbecque (c. 1400 - 1465) Dame excellent ou sont bonté, scavoir Baude Cordier (d. 1397/8?) De tous biens playne (instrumental) Johannes Tinctoris (c. 1435 - 1511?) Margarite, fleur de valeur Gilles Binchois (c. 1400 - 1460) Ce jour de l’an voudray joie mener Guillaume Du Fay Christmas Gloria Spiritus et alme Johannes Ciconia (c. 1370 - 1412) Nato canunt omnia Antoine Brumel Tis concert is sponsored, in part, by the Florence Gould Foundation, Music Before 1800’s programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. -

Informations Utiles À L'intégration De Nouvelles Langues Européennes

Dossier Informations utiles à l'intégration de nouvelles langues européennes recueillies par Holger Bagola (DIR/A-Cellule «Méthodes et développements», section «Formats et systèmes documentaires») Version 1.5 August 2004 Table des matières 0. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................4 1. Les langues ...............................................................................................................................4 2. Les lettres et les caractères spéciaux.........................................................................................5 3. L'encodage ...............................................................................................................................6 4. Les formats ...............................................................................................................................6 5. Les tris ...............................................................................................................................7 6. Les mots «vides» .........................................................................................................................7 7. Vocabulaires harmonisés ...........................................................................................................8 8. Conclusion ...............................................................................................................................8 9. Références ...............................................................................................................................8 -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian As Spoken in MONGOLIA

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian as Spoken in MONGOLIA Halh Mongolian, also known as Khalkha (or Xalxa) Mongolian, is a Mongolic language spoken in Mongolia. It has approximately 3 million speakers. 1. Special handling of dialects There are several Mongolic languages or dialects which are mutually intelligible. These include Chakhar and Ordos Mongol, both spoken in the Inner Mongolia region of China. Their status as separate languages is a matter of dispute (Rybatzki 2003). Halh Mongolian is the only Mongolian dialect spoken by the ethnic Mongolian majority in Mongolia. Mongolian speakers from outside Mongolia were not included in this data collection; only Halh Mongolian was collected. 2. Deviation from native-speaker principle No deviation, only native speakers of Halh Mongolian in Mongolia were collected. 3. Special handling of spelling None. 4. Description of character set used for orthographic transcription Mongolian has historically been written in a large variety of scripts. A Latin alphabet was introduced in 1941, but is no longer current (Grenoble, 2003). Today, the classic Mongolian script is still used in Inner Mongolia, but the official standard spelling of Halh Mongolian uses Mongolian Cyrillic. This is also the script used for all educational purposes in Mongolia, and therefore the script which was used for this project. It consists of the standard Cyrillic range (Ux0410-Ux044F, Ux0401, and Ux0451) plus two extra characters, Ux04E8/Ux04E9 and Ux04AE/Ux04AF (see also the table in Section 5.1). 5. Description of Romanization scheme The table in Section 5.1 shows Appen's Mongolian Romanization scheme, which is fully reversible. -

Chapter 9 5, Or 7, by Reading Clefs and Adding Accidentals to Avoid Franco-Flemish Composers, 1450-1520 the Tritone

17 10. Briefly explain the principal of Missa cuiusvis toni. It's a mass in any mode, so it can be transposed to mode 1, 3, Chapter 9 5, or 7, by reading clefs and adding accidentals to avoid Franco-Flemish Composers, 1450-1520 the tritone 1. [190] What was the style for composers born around 11. Ockeghem's Missa __________ is a double mensuration 1420? (old and new) 1470? (late) canon. Old: formes fixes, cantus firmus works Prolationem New: wider ranges, equality between voices, more imitation Late: end of formes fixes, imitative and homophonic textures, 12. (194) Any questions about the notation and word painting transcription? What are the different procedures of canon? 2. Composers/musicians still depended on _________. Inversion, retrograde England became ________. (189) The rest of Europe (especially the map legend), by marriage or war, was 13. (195) SR: What is a lament? divided into three large areas: Remembrance, eulogy Patrons; insular; Spain, France, Holy Roman Empire 14. What are two important Ockeghem traits? (Germany) Note: It's important to know history, but for Long phrases; elided or overlapping cadences our purposes this section is enough. It gives us a sense of what is going on (and there's a lot of it). 15. (196) Who are the composers of the next generation? Jacob Obrecht (1457-1505), Henricus [Heinrich] Isaac 3. (190) Name the two composers who follow Du Fay. TQ: (c. 1450-1517), Josquin Desprez (c. 1450-1521) [des Any thoughts about the variant spellings? TQ: How Prez in the 8th edition] about pronunciations? Johannes Ockeghem (c.1420-97) and Antoine Busnois 16. -

TLD: Сайт Script Identifier: Cyrillic Script Description: Cyrillic Unicode (Basic, Extended-A and Extended-B) Version: 1.0 Effective Date: 02 April 2012

TLD: сайт Script Identifier: Cyrillic Script Description: Cyrillic Unicode (Basic, Extended-A and Extended-B) Version: 1.0 Effective Date: 02 April 2012 Registry: сайт Registry Contact: Iliya Bazlyankov <[email protected]> Tel: +359 8 9999 1690 Website: http://www.corenic.org This document presents a character table used by сайт Registry for IDN registrations in Cyrillic script. The policy disallows IDN variants, but prevents registration of names with potentially similar characters to avoid any user confusion. U+002D;U+002D # HYPHEN-MINUS -;- U+0030;U+0030 # DIGIT ZERO 0;0 U+0031;U+0031 # DIGIT ONE 1;1 U+0032;U+0032 # DIGIT TWO 2;2 U+0033;U+0033 # DIGIT THREE 3;3 U+0034;U+0034 # DIGIT FOUR 4;4 U+0035;U+0035 # DIGIT FIVE 5;5 U+0036;U+0036 # DIGIT SIX 6;6 U+0037;U+0037 # DIGIT SEVEN 7;7 U+0038;U+0038 # DIGIT EIGHT 8;8 U+0039;U+0039 # DIGIT NINE 9;9 U+0430;U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A а;а U+0431;U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE б;б U+0432;U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE в;в U+0433;U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GHE г;г U+0434;U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE д;д U+0435;U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE е;е U+0436;U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE ж;ж U+0437;U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE з;з U+0438;U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER I и;и U+0439;U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT I й;й U+043A;U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA к;к U+043B;U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL л;л U+043C;U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM м;м U+043D;U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN н;н U+043E;U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O о;о U+043F;U+043F -

Reception of Josquin's Missa Pange

THE BODY OF CHRIST DIVIDED: RECEPTION OF JOSQUIN’S MISSA PANGE LINGUA IN REFORMATION GERMANY by ALANNA VICTORIA ROPCHOCK Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Alanna Ropchock candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree*. Committee Chair: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Committee Member: Dr. L. Peter Bennett Committee Member: Dr. Susan McClary Committee Member: Dr. Catherine Scallen Date of Defense: March 6, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ........................................................................................................... i List of Figures .......................................................................................................... ii Primary Sources and Library Sigla ........................................................................... iii Other Abbreviations .................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... v Abstract ..................................................................................................................... vii Introduction: A Catholic -

Pater Optime:</Italic> Vergilian Allusion In

Pater Optime: Vergilian Allusion in Obrecht's Mille Quingentis The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Gallagher, Sean. 2001. Pater optime: Vergilian allusion in Obrecht's Mille quingentis. Journal of Musicology 18(3): 406-457. Published Version doi:10.1525/jm.2001.18.3.406 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3776966 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Pater optime: Vergilian Allusion in ObrechtÕs Mille quingentis SEAN GALLAGHER A mong the various themes that animate VergilÕs Aeneid, perhaps the most affecting in its persistence is that of a sonÕs duty to his father. Father-son pairs appear throughout the epic, though not surprisingly it is in the depictions of AeneasÕs behavior to- wards his father, Anchises, that the theme of Þlial devotion, with all its emotional and ethical associations, emerges most forcefully. Medieval 406 and renaissance commentators interested in explicating the poem as a Christianized moral or spiritual allegory at times measure AeneasÕs progress against the backdrop of his relationship with his father, a rela- tionship that outlasts even AnchisesÕs death. Indeed, for many readers, ancient and modern alike, AeneasÕs actions following his fatherÕs death constitute the most signiÞcant -

1 Is Selective Attrition Possible in Russian-English Bilinguals? This

Is Selective Attrition Possible in Russian-English Bilinguals? Elena Zaretsky*, Eva G. Bar-Shalom** *University of Massachusetts Amherst, **University of Connecticut, Storrs 1. Introduction This paper reports the results of the study that investigates the language output in L1 (Russian) in a group of Russian-English speaking adults and children. Specifically, it addresses the issue of attrition. By including two groups of subjects, we examined the interaction between the length of uninterrupted exposure to L1, the use of L1 in everyday situation, and the ability to produce correct grammatical structures in L1. The between group comparison was also prompted by the previous notion that adults may undergo less attrition than children (Pallier, 2006). The focus of this particular study is on the assessment of correct production of aspectual forms, as well as other forms of Russian morphosyntax, through the use of two different tasks: the elicited narrative on a picture story book and a Grammaticality Judgment task. The goal of this study was to examine if there is equal loss of all language-specific morphosyntactic structures, including the possibility of aspectual restructuring. Prior research on attrition of L1 Russian in Russian-English bilingual speakers concentrated on the issue of aspectual restructuring, i.e. lexicalization of aspect (Pereltsvaig, 2002). Case marking, lexical and agreement errors were also reported (Polinsky, 2005, Pereltsvaig, in press) in speech production of individuals who continue to use L1 Russian as part of their social interaction. This particular variety of Russian is known as ‘American Russian’ (e.g., Polinsky, 2005, Pereltsvaig, 2002 and in press) and is severely reduced in all aspects of Russian morphosyntax. -

Dictionary of Music.Pdf

The FACTS ON FILE Dictionary of Music The FACTS ON FILE Dictionary of Music Christine Ammer The Facts On File Dictionary of Music, Fourth Edition Copyright © 2004 by the Christine Ammer 1992 Trust All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ammer, Christine The Facts On File dictionary of music / Christine Ammer.—4th ed. p. cm. Includes index. Rev. ed. of: The HarperCollins dictionary of music. 3rd ed. c1995. ISBN 0-8160-5266-2 (Facts On File : alk paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3009-5 (e-book) 1. Music—Dictionaries. 2. Music—Bio-bibliography. I. Title: Dictionary of music. II. Ammer, Christine. HarperCollins dictionary of music. III. Facts On File, Inc. IV. Title. ML100.A48 2004 780'.3—dc22 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by James Scotto-Lavino Cover design by Semadar Megged Illustrations by Carmela M. Ciampa and Kenneth L. Donlan Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint an excerpt from Cornelius Cardew’s “Treatise.” Copyright © 1960 Hinrichsen Edition, Peters Edition Limited, London. -

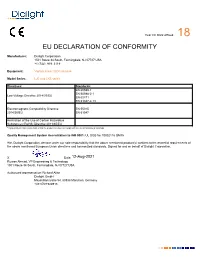

Eu Declaration of Conformity

Year CE Mark Affixed: 18 EU DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY Manufacturer: Dialight Corporation 1501 Route 34 South, Farmingdale, NJ 07727 USA +1 (732) 919 3119 Equipment: Vigilant linear LED luminaire Model Series: LJE and LKE series Directives: Standards: EN 60598-1 EN 60598-2-1 Low Voltage Directive 2014/35/EU EN 62471 EN 61347-2-13 Electromagnetic Compatibility Directive EN 55015 2014/30/EU EN 61547 Restriction of the Use of Certain Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive 2011/65/EU * A gap analysis has been performed and the product continues to comply with the latest harmonized standards. Quality Management System Accreditation to ISO 9001: UL DQS file 10002116 QM15 We, Dialight Corporation, declare under our sole responsibility that the above mentioned product(s) conform to the essential requirements of the above mentioned European Union directives and harmonized standards. Signed for and on behalf of Dialight Corporation. X_________________________________ Date:________________12-Aug-2021 Rizwan Ahmad, VP Engineering & Technology 1501 Route 34 South, Farmingdale, NJ 07727 USA Authorized representative: Richard Allan Dialight GmbH Maximilianstraße 54, 80538 München, Germany +49 8709 924913 Jahr der CE-Kennzeichnung: 18 EG-KONFORMITÄTSERKLÄRUNG Hersteller: Dialight Corporation 1501 Route 34 South, Farmingdale, NJ 07727 USA +1 (732) 919 3119 Produkt: Vigilant linear LED luminaire Modellreihen: LJE and LKE series Richtlinien: Normen: EN 60598-1 EN 60598-2-1 Niederspannungsrichtlinie 2014/35/EU EN 62471 EN 61347-2-13 Richtlinie über die elektromagnetische EN 55015 Verträglichkeit 2014/30/EU EN 61547 Richtlinie zur Beschränkung der Verwendung bestimmter gefährlicher Stoffe (RoHS) 2011/65/EU * Die Durchführung einer Lückenanalyse hat ergeben, dass das Produkt den aktuellen harmonisierten Normen entspricht.