Pater Optime:</Italic> Vergilian Allusion In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

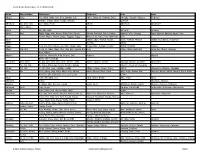

Adult Jail Booking August 1, 2020 to July 31, 2021 As of August 6, 2021

Adult Jail Booking August 1, 2020 to July 31, 2021 as of August 6, 2021 Book of Arrest Number Last Name First Name 220012420 NEWSOME LATREY 220012420 NEWSOME LATREY 220012420 NEWSOME LATREY 220012421 DONATIELLO CHARLES 220012421 DONATIELLO CHARLES 220012422 TONASKET MALAKAI 220012423 BURRIS ALLEN 220012424 LOPEZ-VARGAS HECTOR 220012425 RONNIE ANDRE 220012425 RONNIE ANDRE 220012426 CRUZ-GARCIA SAUL 220012426 CRUZ-GARCIA SAUL 220012427 LEWIS MICHAEL 220012427 LEWIS MICHAEL 220012428 KENNEBREW EVERETT Page 1 of 1370 10/02/2021 Adult Jail Booking August 1, 2020 to July 31, 2021 as of August 6, 2021 Middle Name JrSr Booking Date Time PIERRE-PELTON 08/01/2020 12:10:00 AM PIERRE-PELTON 08/01/2020 12:10:00 AM PIERRE-PELTON 08/01/2020 12:10:00 AM PHILLIP 3 08/01/2020 12:41:00 AM PHILLIP 3 08/01/2020 12:41:00 AM RAY 08/01/2020 01:23:00 AM RAY 08/01/2020 02:08:00 AM 08/01/2020 12:39:00 AM LAMONT 08/01/2020 02:12:00 AM LAMONT 08/01/2020 02:12:00 AM 08/01/2020 02:27:00 AM 08/01/2020 02:27:00 AM RYAN 08/01/2020 02:02:00 AM RYAN 08/01/2020 02:02:00 AM JAMES 08/01/2020 02:33:00 AM Page 2 of 1370 10/02/2021 Adult Jail Booking August 1, 2020 to July 31, 2021 as of August 6, 2021 Release Date Time Current Facility Charge 08/20/2020 08:29:00 AM ROBBERY INV 08/20/2020 08:29:00 AM THEFT 08/20/2020 08:29:00 AM ASSAULT 08/19/2020 06:25:00 PM BURGLARY INV 08/19/2020 06:25:00 PM BURG 2 08/01/2020 07:18:00 PM ASSAULT INV 08/03/2020 06:45:00 PM ASSAULT 4 (DV) 08/01/2020 04:45:00 AM DUI 08/06/2020 04:05:00 PM FEL HARASS INV 08/06/2020 04:05:00 PM FTA POS DRG PARA 08/01/2020 07:18:00 PM D.W.I. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

2020 Commencement Program (Download PDF)

FLORIDA STATE COLLEGE AT JACKSONVILLE COMMENCEMENT CEREMONY 5VIRTUAL CEREMONY MISSION STATEMENT JULY 2, 2020rd Florida State College at Jacksonville provides high value, relevant life-long education that enhances the intellectual, social, cultural and economic development of our diverse community. VISION STATEMENT Florida State College at Jacksonville...Growing minds today, leading tomorrow’s world. 3 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE PROGRAM NATIONAL ANTHEM .................................................................................................... FSCJ Chorale Student Ms. Melissa Caceres WELCOMING REMARKS AND COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS ............................................ Dr. John Avendano President, Florida State College at Jacksonville A MESSAGE FROM THE COLLEGE PRESIDENT INTRODUCTION OF STUDENT SPEAKER ........................................................................ Dr. John Woodward TO OUR GRADUATES President, Faculty Senate Greetings and Congratulations FSCJ Graduate, STUDENT REMARKS ......................................................................................................Ms. SeQoya Williams Collegewide President, Student Government Association We are pleased to celebrate FSCJ’s 2020 Commencement Ceremony as we honor our graduates and all they have overcome to reach this milestone! The College community REMARKS ............................................................................................................Mr. Thomas R. McGehee Jr. looks forward to celebrating our graduates each and every year. While -

FLUXNET: a New Tool to Study the Temporal and Spatial Variability of Ecosystem-Scale Carbon Dioxide, Water Vapor, and Energy Flux Densities

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Numerical Terradynamic Simulation Group Publications Numerical Terradynamic Simulation Group 11-2001 FLUXNET: A New Tool to Study the Temporal and Spatial Variability of Ecosystem-Scale Carbon Dioxide, Water Vapor, and Energy Flux Densities Dennis Baldocchi Eva Falge Lianhong Gu Richard Olson D. Y. Hollinger See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/ntsg_pubs Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Baldocchi, D. D., Falge E., Gu L., Olson R., Hollinger D. Y., Running S. W., Anthoni P., Bernhofer Ch., Davis K. J., Evans R., Fuentes J., Goldstein A., Katul G., Law B. E., Lee X., Malhi Y., Meyers T. P., Munger J. W., Oechel W. C., Paw U K. T., Pilegaard K., Schmid H. P., Valentini R., Verma S., Vesala T., Wilson K. B., and Wofsy S. C. (2001). FLUXNET: A New Tool to Study the Temporal and Spatial Variability of Ecosystem- Scale Carbon Dioxide, Water Vapor, and Energy Flux Densities. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 82: 2415-2434, doi: 10.1175/1520-0477(2001)082<2415:FANTTS>2.3.CO;2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Numerical Terradynamic Simulation Group at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Numerical Terradynamic Simulation Group Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Dennis Baldocchi, Eva Falge, Lianhong Gu, Richard Olson, D. Y. -

CMF Fraternity English 2020.Indd

Claretian Fraternity News Bulletin for Families and Associates, Province of Bangalore, Vol. 10, 2020 May the Joy and Peace of Christmas be with you all through the New Year. Wishing you a season of blessings from God. Merry Christmasand Prosp erous New Year2021 MESSAGE FROM THE DELEGATE SUPERIOR n 24th October 2020 we celebrated the 150th death The year 2020 is also remarkable O anniversary of our Founder St. Antony Mary Claret. for the Indian Claretians in a very Eighty years after his death Pope Pius XII proclaimed him a special way as our Congregation saint in 1950, formally recognizing that he heroically practiced is completing fi fty years of its the Christian virtues and presenting him to the universal existence and ministry in our Church as an example to follow. Fr. Claret founded religious Country. It was in 1970 that the Congregations of men and women, whose members are fi rst Claretian community was now at the service of the Word of God in over sixty countries. established in a small village in These missionaries give testimony to the Gospel values in Kerala called Kuravilangad, and the past fi fty years have brought different ways, namely through direct preaching of the Word to us immeasurable divine blessings. The small community of God, social and charitable activities in favour of the poor, started with three priests, fi ve novices and a small batch of educational ministry, pastoral service in the local Churches minor seminarians have grown today to a community of over etc. The life of St. Claret has motivated so many young men 550 priests and a good number of seminarians at different that the Claretian Congregation has given to the Church nearly stages of their formation, grouped under fi ve Major Organisms, three hundred martyrs, consisting of priests, lay brothers and namely three full-fl edged Provinces and two independent seminarians, during the Spanish civil war. -

Baby Boy Names Registered in 2008 January 2008

Page 1 of 37 Baby Boy Names Registered in 2008 January 2008 # Baby Boy Names # Baby Boy Names # Baby Boy Names 1 A. 2 Abdulkadir 1 Adeshwar 2 A.J 1 Abdul-Kareem 1 Adhal 8 Aaden 1 Abdulla 3 Adham 1 Aadesh 15 Abdullah 2 Adian 1 Aadi 1 Abdullaha 1 Adil 2 Aadil 1 Abdul-Mannan 1 Adison 1 Aadit 2 Abdulrahman 4 Aditya 1 Aadon 1 Abdulrahmman 1 Adjani 1 Aadyn 1 Abdulrazzak 1 Adlai 1 Aahil 1 Abdulwahid 3 Adler 1 Aaidan 1 Abdur-Raafay 1 Adnan 1 Aameen 1 Abdus 1 Adolfo 1 Aamir 1 Abdusalam 1 Adonaël 4 Aarav 1 Abe 1 Adonis 1 Aarin 1 Abeer 1 Adonnis 1 Aarish 1 Abeghoni 35 Adrian 1 Aariz 6 Abel 1 Adrianne 59 Aaron 1 Abel-Befekadu 1 Adriano 1 Aaroosh 1 Abele 1 Adrianos 1 Aarry 1 Abenezer 1 Adriatik 1 Aarshin 1 Abhaydeep 1 Adriel 1 Aarvin 1 Abhayjeet 4 Adrien 6 Aaryan 1 Abhijitpal 2 Adris 1 Aashay 1 Abhinav 1 Adym 5 Aayan 1 Abhishek 6 Aedan 1 Aazan 1 Abhyuday 2 Aeden 7 Abbas 1 Abiel 2 Aedyn 1 Abd 1 Abiheek 1 Aekam 1 Abdallah 1 Abo-Bakeir 1 Aengus 1 Abdarrahman 5 Abraham 3 Aeron 1 Abdel 2 Abram 1 Aeshan 1 Abdel-All 1 Abramham 1 Aeson 1 Abdelmoumen 1 Abriel 1 Afanasi 1 Abd-ElRahman 1 Abshir 1 Afnan 1 Abdel-Rahman 1 Absolom 1 Aganj 1 Abderrahman 1 Abu 1 Aganze 1 Abdi 1 Acdous 1 Agoth 1 Abdikarim 2 Ace 1 Aguer 1 Abdinajib 1 Achal 2 Agustin 1 Abdinasir 1 Acheil 1 Ahad 3 Abdirahman 1 Achilles 1 Ahkhasa 1 Abdirahman-Afi 1 Achmad 11 Ahmad 1 Abdisatar 121 Adam 1 Ahmar 1 Abdourrahman 3 Adan 21 Ahmed 11 Abdul 1 Addam 1 Ahmed-Kader 1 Abdulah 6 Addison 2 Ahmet 1 Abdulallah 1 Addon 1 Ahnaf 1 Abdul-Barry 1 Adee 1 Ahsan 1 Abdulbasit 2 Adem 1 Ahyaan 1 Abdul-Hakeem 14 Aden -

BH Program FINAL

MUSIC BEFORE 1800 Louise Basbas, Director Blue Heron Christmas at the Courts of 15th-Century France & Burgundy Scott Metcalfe, director and harp Jennifer Ashe, Pamela Dellal, Martin Near, Daniela Tosic Michael Barrett, Owen McIntosh, Jason McStoots, Stefan Reed, Mark Sprinkle, Sumner Tompson Cameron Beauchamp, Paul Guttry Laura Jeppesen, vielle and rebec; Charles Weaver, lute and voice Advent O clavis David (O-antiphon for December 20) plainchant Factor orbis Jacob Obrecht (1457/8 - 1505) O virgo virginum (O-antiphon for December 24) plainchant O virgo virginum Josquin Desprez (c. 1455 - 1521) Conditor alme siderum (alternatim hymn for Advent) Guillaume Du Fay (c. 1397 - 1474) Ave Maria gratia dei plena Antoine Brumel (c. 1460 - c. 1512) Christmas O admirabile commercium / Verbum caro factum est Johannes Regis (c. 1425 - 1426) INTERMISSION Christmas Letabundus (Christmas sequence) Guillaume Du Fay Praeter rerum seriem Adrian Willaert (c. 1490 - 1562 New Year’s Day La plus belle et doulce figure Nicolas Grenon (c. 1380 - 1456) Dieu vous doinst bon jour et demy Guillaume Malbecque (c. 1400 - 1465) Dame excellent ou sont bonté, scavoir Baude Cordier (d. 1397/8?) De tous biens playne (instrumental) Johannes Tinctoris (c. 1435 - 1511?) Margarite, fleur de valeur Gilles Binchois (c. 1400 - 1460) Ce jour de l’an voudray joie mener Guillaume Du Fay Christmas Gloria Spiritus et alme Johannes Ciconia (c. 1370 - 1412) Nato canunt omnia Antoine Brumel Tis concert is sponsored, in part, by the Florence Gould Foundation, Music Before 1800’s programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. -

Funeral / Burial Date Last Name First M. Box January 8, 1926 Mawby William W

Memorial Funeral Home (Please contact us for assistance) Plainfield Public Library Indexed Records, 1927 to 1970 [Bulk Dates: 1926-1971] page 1 of 163 Funeral / Burial Date Last Name First M. Box January 8, 1926 Mawby William W. 30 January 28, 1927 Braun Robert 26 January 3, 1928 Conover Gertrude Rowena 27 June 1, 1928 Bieling Charles A. 26 June 16, 1928 Phillips Charles Milton 30 June 30, 1928 James Helen M. M. 29 August 9, 1928 Mumby Albert H. 30 August 20, 1928 Benbrook Julia Ann 26 August 25, 1928 Miller Catherine A. 30 September 5, 1928 Tier William N. 32 September 22, 1928 Wilson Elizabeth 32 September 29, 1928 Coddington Harrison 27 October 22, 1928 Schiotis George Thomas 31 November 7, 1928 Morcom Thomas 30 November 10, 1928 Madsen Baby Girl 30 November 15, 1928 Van Doren Anenetta 32 November 19, 1928 Ruckert Florence 31 November 20, 1928 Bodine Sarah Shipman 26 November 23, 1928 Leek William C. 29 December 1, 1928 Olsson Bertha M. 30 December 2, 1928 Mundy David E. 30 December 6, 1928 Doane Thaddeus O. 27 December 10, 1928 Lunger Bessie Blood 29 December 20, 1928 Rockefellow Anna Frances 31 January 2, 1929 Harriger Betty Louise 28 January 5, 1929 Dunkel Maria A. 27 January 12, 1929 Edel Fannia 27 January 18, 1929 Hinman Alphonsine C. 28 January 23, 1929 Johnson John Peter 29 January 29, 1929 La Matty Libbie A. 29 February 8, 1929 Donaldson Don McK. 27 February 12, 1929 Beitar William C. 26 February 13, 1929 Colthar John M. 27 February 18, 1929 Almes Marie Claire 26 February 25, 1929 Mc Queen Margaret D. -

The 2011 Dams of Distinction List Honors the Hereford Breed's Cows Who Meet the Highest Standard of Production and Recognizes the Cattlemen Who Produce Them

The 2011 Dams of Distinction list honors the Hereford breed's cows who meet the highest standard of production and recognizes the cattlemen who produce them. 2011 Dams of Distinction Honored The job description for an ideal Hereford cow could be as follows: She should produce a healthy, growthy calf every year; she should calve as a two-year-old, and she should cause her owner absolutely no problems. These ideal cows are recognized as Dams of Distinction. A Dam of Distinction is the standard by which all Hereford cows can be judged. In order to be honored as a Dam of Distinction, a cow must have 1) Weaned a calf born since January 1, 2010. 2) Produced at least 3 calves. 3) Initially calved at 30 months of age or less. 4) Had an interval between the first and second calves of no greater than 400 days. In addition, a 370-day calving interval must have been maintained after her second calf. The longer initial calving interval allows breeders to calve two-year-old heifers prior to the mature cow herd. 5) Every calf produced that was born before June 30, 2011 must have weaning records submitted to the Hereford Performance Program. 6) A progeny average 205-day adjusted weaning weight ratio of at least 105. These are the cows that meet the highest standards of commercial cattle production. The cow must do her job, but also her owner must manage the herd correctly to give her the opportunity to excel. Only a small portion of active cows is recognized. -

Chapter 9 5, Or 7, by Reading Clefs and Adding Accidentals to Avoid Franco-Flemish Composers, 1450-1520 the Tritone

17 10. Briefly explain the principal of Missa cuiusvis toni. It's a mass in any mode, so it can be transposed to mode 1, 3, Chapter 9 5, or 7, by reading clefs and adding accidentals to avoid Franco-Flemish Composers, 1450-1520 the tritone 1. [190] What was the style for composers born around 11. Ockeghem's Missa __________ is a double mensuration 1420? (old and new) 1470? (late) canon. Old: formes fixes, cantus firmus works Prolationem New: wider ranges, equality between voices, more imitation Late: end of formes fixes, imitative and homophonic textures, 12. (194) Any questions about the notation and word painting transcription? What are the different procedures of canon? 2. Composers/musicians still depended on _________. Inversion, retrograde England became ________. (189) The rest of Europe (especially the map legend), by marriage or war, was 13. (195) SR: What is a lament? divided into three large areas: Remembrance, eulogy Patrons; insular; Spain, France, Holy Roman Empire 14. What are two important Ockeghem traits? (Germany) Note: It's important to know history, but for Long phrases; elided or overlapping cadences our purposes this section is enough. It gives us a sense of what is going on (and there's a lot of it). 15. (196) Who are the composers of the next generation? Jacob Obrecht (1457-1505), Henricus [Heinrich] Isaac 3. (190) Name the two composers who follow Du Fay. TQ: (c. 1450-1517), Josquin Desprez (c. 1450-1521) [des Any thoughts about the variant spellings? TQ: How Prez in the 8th edition] about pronunciations? Johannes Ockeghem (c.1420-97) and Antoine Busnois 16. -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

First Name Translations

First Name Translations English Latin Polish German Adalbert Adalbertus Wojciech Adalbart Adam Adamus Adam Adam Adeline Adhelina Adelina,Adela Adeline Agnes Agnetta Agnieszka Agnes Albert Albertus Albert Albrecht Alfred Alberdus, Aluredus Alfred Alffred Alice Aelizia, Alecia Alicia, Alicya Adelcia Aloysius Aloysius Alojzy Ambrose Ambrosius Ambrozy Ambrosius Andrew Andreus Andrzej Andreas Anthony Anthonius Anton Anthoni Arthur Arcturus Artur Artur August Augustinus August Augustine Batrholomew Bartholomeaus Bartolomiej Barthel Benedict Benedictus Benedykt Benedikt Blasé Blasius Blazej Blasius Bridget Brigitta Brygida Brigette Carl Carolus Karol Karl Caroline Karolina Charlotte, Karoline Catherine Catherina Katarzyna Katharina, Katerine Cecilia Ceelia Cecylia Cilli Charles Carolus Karol Karl Casimir Casiminus Kazimierz Kasimir Charlotte Wladyslawa Charlotte Chester Czeslaus Czeslaw Christian Krystian Christian Christine Christina Kyrstyna Christine Christopher Christophorus, Xporferus Krysztof Christoph Clara Clara Klara Clare Clement Clement Klement Constance Constantia Konstancya Constantia Constantine Constantine Kostanty Konstantin David Davidus Dawid David Denis Dionysius Dyonizy Dionysios Demitrius Dimitrius Dymitry Demetrius Dorothy Dorothea Dorota Dorothea Eleanor Alianora, Elianora Elonora Eleonore Elizabeth Elizabetha Elzbieta Elisabetha Fabian Fabian Fabjan Fabe Faith Fides Nadzieja Felice Felicia Felicya Felicia Frances Francisca Franciszka Franziska Francis Franciscus Franciszek Frantz, Franz Frank Francus Franciszek Frantz,