1 Is Selective Attrition Possible in Russian-English Bilinguals? This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unicode Request for Cyrillic Modifier Letters Superscript Modifiers

Unicode request for Cyrillic modifier letters L2/21-107 Kirk Miller, [email protected] 2021 June 07 This is a request for spacing superscript and subscript Cyrillic characters. It has been favorably reviewed by Sebastian Kempgen (University of Bamberg) and others at the Commission for Computer Supported Processing of Medieval Slavonic Manuscripts and Early Printed Books. Cyrillic-based phonetic transcription uses superscript modifier letters in a manner analogous to the IPA. This convention is widespread, found in both academic publication and standard dictionaries. Transcription of pronunciations into Cyrillic is the norm for monolingual dictionaries, and Cyrillic rather than IPA is often found in linguistic descriptions as well, as seen in the illustrations below for Slavic dialectology, Yugur (Yellow Uyghur) and Evenki. The Great Russian Encyclopedia states that Cyrillic notation is more common in Russian studies than is IPA (‘Transkripcija’, Bol’šaja rossijskaja ènciplopedija, Russian Ministry of Culture, 2005–2019). Unicode currently encodes only three modifier Cyrillic letters: U+A69C ⟨ꚜ⟩ and U+A69D ⟨ꚝ⟩, intended for descriptions of Baltic languages in Latin script but ubiquitous for Slavic languages in Cyrillic script, and U+1D78 ⟨ᵸ⟩, used for nasalized vowels, for example in descriptions of Chechen. The requested spacing modifier letters cannot be substituted by the encoded combining diacritics because (a) some authors contrast them, and (b) they themselves need to be able to take combining diacritics, including diacritics that go under the modifier letter, as in ⟨ᶟ̭̈⟩BA . (See next section and e.g. Figure 18. ) In addition, some linguists make a distinction between spacing superscript letters, used for phonetic detail as in the IPA tradition, and spacing subscript letters, used to denote phonological concepts such as archiphonemes. -

Informations Utiles À L'intégration De Nouvelles Langues Européennes

Dossier Informations utiles à l'intégration de nouvelles langues européennes recueillies par Holger Bagola (DIR/A-Cellule «Méthodes et développements», section «Formats et systèmes documentaires») Version 1.5 August 2004 Table des matières 0. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................4 1. Les langues ...............................................................................................................................4 2. Les lettres et les caractères spéciaux.........................................................................................5 3. L'encodage ...............................................................................................................................6 4. Les formats ...............................................................................................................................6 5. Les tris ...............................................................................................................................7 6. Les mots «vides» .........................................................................................................................7 7. Vocabulaires harmonisés ...........................................................................................................8 8. Conclusion ...............................................................................................................................8 9. Références ...............................................................................................................................8 -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian As Spoken in MONGOLIA

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian as Spoken in MONGOLIA Halh Mongolian, also known as Khalkha (or Xalxa) Mongolian, is a Mongolic language spoken in Mongolia. It has approximately 3 million speakers. 1. Special handling of dialects There are several Mongolic languages or dialects which are mutually intelligible. These include Chakhar and Ordos Mongol, both spoken in the Inner Mongolia region of China. Their status as separate languages is a matter of dispute (Rybatzki 2003). Halh Mongolian is the only Mongolian dialect spoken by the ethnic Mongolian majority in Mongolia. Mongolian speakers from outside Mongolia were not included in this data collection; only Halh Mongolian was collected. 2. Deviation from native-speaker principle No deviation, only native speakers of Halh Mongolian in Mongolia were collected. 3. Special handling of spelling None. 4. Description of character set used for orthographic transcription Mongolian has historically been written in a large variety of scripts. A Latin alphabet was introduced in 1941, but is no longer current (Grenoble, 2003). Today, the classic Mongolian script is still used in Inner Mongolia, but the official standard spelling of Halh Mongolian uses Mongolian Cyrillic. This is also the script used for all educational purposes in Mongolia, and therefore the script which was used for this project. It consists of the standard Cyrillic range (Ux0410-Ux044F, Ux0401, and Ux0451) plus two extra characters, Ux04E8/Ux04E9 and Ux04AE/Ux04AF (see also the table in Section 5.1). 5. Description of Romanization scheme The table in Section 5.1 shows Appen's Mongolian Romanization scheme, which is fully reversible. -

TLD: Сайт Script Identifier: Cyrillic Script Description: Cyrillic Unicode (Basic, Extended-A and Extended-B) Version: 1.0 Effective Date: 02 April 2012

TLD: сайт Script Identifier: Cyrillic Script Description: Cyrillic Unicode (Basic, Extended-A and Extended-B) Version: 1.0 Effective Date: 02 April 2012 Registry: сайт Registry Contact: Iliya Bazlyankov <[email protected]> Tel: +359 8 9999 1690 Website: http://www.corenic.org This document presents a character table used by сайт Registry for IDN registrations in Cyrillic script. The policy disallows IDN variants, but prevents registration of names with potentially similar characters to avoid any user confusion. U+002D;U+002D # HYPHEN-MINUS -;- U+0030;U+0030 # DIGIT ZERO 0;0 U+0031;U+0031 # DIGIT ONE 1;1 U+0032;U+0032 # DIGIT TWO 2;2 U+0033;U+0033 # DIGIT THREE 3;3 U+0034;U+0034 # DIGIT FOUR 4;4 U+0035;U+0035 # DIGIT FIVE 5;5 U+0036;U+0036 # DIGIT SIX 6;6 U+0037;U+0037 # DIGIT SEVEN 7;7 U+0038;U+0038 # DIGIT EIGHT 8;8 U+0039;U+0039 # DIGIT NINE 9;9 U+0430;U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A а;а U+0431;U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE б;б U+0432;U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE в;в U+0433;U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GHE г;г U+0434;U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE д;д U+0435;U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE е;е U+0436;U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE ж;ж U+0437;U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE з;з U+0438;U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER I и;и U+0439;U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT I й;й U+043A;U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA к;к U+043B;U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL л;л U+043C;U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM м;м U+043D;U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN н;н U+043E;U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O о;о U+043F;U+043F -

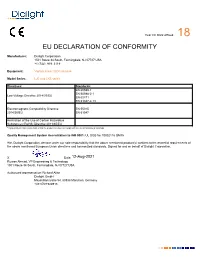

Eu Declaration of Conformity

Year CE Mark Affixed: 18 EU DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY Manufacturer: Dialight Corporation 1501 Route 34 South, Farmingdale, NJ 07727 USA +1 (732) 919 3119 Equipment: Vigilant linear LED luminaire Model Series: LJE and LKE series Directives: Standards: EN 60598-1 EN 60598-2-1 Low Voltage Directive 2014/35/EU EN 62471 EN 61347-2-13 Electromagnetic Compatibility Directive EN 55015 2014/30/EU EN 61547 Restriction of the Use of Certain Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive 2011/65/EU * A gap analysis has been performed and the product continues to comply with the latest harmonized standards. Quality Management System Accreditation to ISO 9001: UL DQS file 10002116 QM15 We, Dialight Corporation, declare under our sole responsibility that the above mentioned product(s) conform to the essential requirements of the above mentioned European Union directives and harmonized standards. Signed for and on behalf of Dialight Corporation. X_________________________________ Date:________________12-Aug-2021 Rizwan Ahmad, VP Engineering & Technology 1501 Route 34 South, Farmingdale, NJ 07727 USA Authorized representative: Richard Allan Dialight GmbH Maximilianstraße 54, 80538 München, Germany +49 8709 924913 Jahr der CE-Kennzeichnung: 18 EG-KONFORMITÄTSERKLÄRUNG Hersteller: Dialight Corporation 1501 Route 34 South, Farmingdale, NJ 07727 USA +1 (732) 919 3119 Produkt: Vigilant linear LED luminaire Modellreihen: LJE and LKE series Richtlinien: Normen: EN 60598-1 EN 60598-2-1 Niederspannungsrichtlinie 2014/35/EU EN 62471 EN 61347-2-13 Richtlinie über die elektromagnetische EN 55015 Verträglichkeit 2014/30/EU EN 61547 Richtlinie zur Beschränkung der Verwendung bestimmter gefährlicher Stoffe (RoHS) 2011/65/EU * Die Durchführung einer Lückenanalyse hat ergeben, dass das Produkt den aktuellen harmonisierten Normen entspricht. -

Speech by Federal President Frank Walter Steinmeier at the New Year Reception for the Diplomatic Corps in Schloss Bellevue on 14 January 2019

The speech online: www.bundespraesident.de page 1 to 3 Speech by Federal President Frank Walter Steinmeier at the New Year reception for the Diplomatic Corps in Schloss Bellevue on 14 January 2019 How wonderful it is to see you all again! Last June, we visited the Hanseatic City of Bremen together. We sat beneath metre-long models of ships, traced the footsteps of Elvis Presley, and walked from the South Sea to the North Pole in the Klimahaus within the space of just one hour. And we also watched football together. Ambassador Jong, we were party to a nail-biting 90 minutes, and even a bit longer if I add the extra time. In the end, the South Korean team won deservedly. And this is football we’re talking about! In handball, the opposite was the case at the opening of the World Cup. Germany won against the joint team for North and South Korea. That’s how the pebble rocks in sport. There can only ever be one winner in what is a classic zero-sum game. One team wins, the other loses. This is all very well if the outcome is sporting fairness. Such fairness seems increasingly to be falling by the wayside in international relations, however. When I read reports about international summits, then this zero-sum logic of “every man for himself” or, even worse, “everyone against everyone else” has gained in traction. The belief that cooperation and clearly defined rules stand to benefit all those involved is being called into question ever more openly. -

Pri Kaz Ge Ne Ral Nih Re Šen Ja Od Vo Đen Ja Upo Treb Lje

UDK: 628.3(497.11) Ljil ja na Janković*, Mo mči lo Drakulić**, Mi loš Stanić*, Du šan Prodanović*, Žel jko Vasilić* Prikaz generalnih RE šenja odvođenja upotrebljenih I KI šNIH voda naselja Brus I Blace Display OF general solutions FOR DISPOSAL OF WASTE AND STORM waters IN THE villages Blace AND Brus Rezime U ovom radu su pri ka za na ge ne ral na re šen ja od vo đen ja upo treb lje ne i at mo sfer ske vo de na sel ja Brus i Bla ce ko ji su pri pre ma ni u ok vi ru IPA III kom po nen te PPF4 - Pro ject Pre pa ra tion Fa ci lity 4, IPA 2010. Za kon ska re gu la tiva ko ja se od nosi na od vo đen je upo treb- l j e n i h v o d a - D i r e k t i v e E U , u k l j u č u j u ć i i D i r e k t i v u o g r a d s k i m o t p a d n i m v o d a m a , u s m e r a v a k a o d a b i r a n j u s e p a r a c i o n i h s i s t e m a z a p r i k u p l j a n j e i o d v o đ e n j e u p o t r e b l j e n i h i a t m o s f e r s k i h v o d a i p r e č i š ć a v a n j e u p o t r e b l j e n i h v o d a u p o s t r o j e n jima za pre č i š ć a v a n j e p r e i s p u š t a n j a u p r i j e m n i ke. -

Transliteration of Cyrillic for Use in Botanical Nomenclature Author(S): Jiří Paclt Source: Taxon, Vol

Transliteration of Cyrillic for Use in Botanical Nomenclature Author(s): Jiří Paclt Source: Taxon, Vol. 2, No. 7 (Oct., 1953), pp. 159-166 Published by: International Association for Plant Taxonomy (IAPT) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1216489 . Accessed: 18/09/2011 13:52 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. International Association for Plant Taxonomy (IAPT) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Taxon. http://www.jstor.org prove of value for each worker whose can be predicted that in the near future a endeavors touch the Characeae. If shortcut significant acceleration in the progress and name-stabilizing legislation can be pre- toward a workable taxonomic treatment of vented, and if blind acceptance of authority Characeae through thb efforts of numerous can be replaced by reliance upon facts; it workers will be witnessed. Transliteration of Cyrillic for use in botanical nomenclature I. Materials for a Proposal to be submitted to the Paris Congress by JIRi PACLT (Bratislava) The world-wide use of Roman characters sound (phonetic rendering) or that of letter in scientific and other literature makes it for letter. He usually decides on a com- desirable to introduce a uniform method of promise between the two (Fig. -

David Fallows Lnfluences on Josquin

David Fallows lnfluences on Josquin Five hundred years ago Ottaviano Petrucci published a book with the simple title Misse Josquin. That may be the first such Statement of auctoritas in music. Earlier monographic volumes were devoted to the work of Guillaume de Ma- chaut and Adam de la Halle, for example, but these were part of a literary tradi- tion, containing primarily poetry: there are many manuscript books devoted to the work of a single poet or literary figure, reaching back hundreds of years before Petrucci's Misse ]osquin. But there is almost no evidence of such books in music before September 1502. One could say the same about the history of ascriptions in music. Before about 1400 any such ascriptions in the musical sources are again within a lite- rary tradition - for exan1ple in the troubadour and trouvere manuscripts - and may in most cases acrually concern the poet rather than the composer. Then in the first decade of the fifteenth century there are guite suddenly a lot of manu- scripts of polyphony that give the composers' names: the Chantilly Codex (F- CH, MS 564), the main Trecento manuscripts, the Mancini Codex (I-La, MS 184), and so on. So the very habit of musical ascription was only about a hundred years old when Petrucci published that book devoted for the first time to the work of a single composer. And it is easy to go on from there and agree that there was a good reason why Petrucci featured a single composer: like so many music pub- lishers after him he knew that one of the easiest ways of selling a book was to seil the author, to seil, in fact, by auctoritas. -

FORT'. DE LA ·Soulaye

Reproduced from the Unclassified I Declassified Holdings of the National Archives ....... ··.... ~ ··- ... --· -···-··-.~... -""="""""""""""'""- ....-:. THE:~_MISSISSIPPI.. FORT~ .. CALLED / FORT'. DE LA ·soULAYE. , .by . MAURICE RIES • .. M •• r~ :' 0 -~ :· •': M ,•'. • • ''.•' •, ~ T • ' . Reprinted f~~m _, THE. LOUISIANA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY '. Vol•. 19, No. 4~ ·."O~toher, 1936 . ) . ' . '·~::,. .•; ... :::,, Reproduced from the Unclassiried I Declassified Holdings of the National Archives . :_ ·• , ' ..... -.·····..:~~ t • I -. I I ··- ~ I. I THE MISSISSIPPI FORT, CALL~D FORT DE LA BOULAYE, I " (1700-1715) '·. THE FIRST F.RENCH' SETTLEMENT IN .PRESENT-DAY LOUISIANA - .A Report by Gordon W. Callender, Prescott H. F. Follett, · ·!> ... · ·.Albert Lieutaud and Maurice Ries , ... :·•.' '·, -..,_")( ... ·Written" by MAURICE RIES· t· DEDICATION I. _J... ·· To the memory of the Fre:r.ich pione~rs in Louisiana, to that of Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville; and of the Sieur de la Boulaye; and the Comite F:r.ance-Amerique also, this 'memoir of the forgotten fort is respectfully dedicated .. ~iWi:8~~Bfhl1!!w~J.1i.~ii~~§ilWfoi~in~·sromti·0;f':iational<Archives.,i.~,·'· .. .... ·-· • -.·---.:.~.~ ... .. ~ . .~:---~--- -----1 - . "\ ""' 4 The Louisiana Historical Quarterly CONTENTS ·Foreword. Figure A: Fort de la Boulaye and its Geographic Area. Figure B: Detailed Map of Site of Fort de la Boulaye. ·Figure C: Parts of cypress logs from foundation of the Fort. Figure D : Cannon-ball found on site of the Fort. , .. ~Chap~er . · I : Introduction. ,. qhapter~-=-~ I_I: The Source-Materials . ..... '' ~Ch~pter }II:· 'Summary and Conclusions.. Appendix · i:. Maps of the region of the Fort. '. 'App~ndi;K 2: Affidavits . ,· . Appendix ·3 : Recognition. Bibliography. l .... ·-· • -.--..:~.:... ... .... .- ·_:___ -~-_.__L ~ : I ...... ..;;.._; .... .., .. The Mississippi Fort,· Called Fort De La Boulaye 5 FOREWORD \. -

EL Ένα Ena AL Një Nie DE Eins Ains EN

EL Ένα Ena AL Një Nie DE eins ains EN one Wan ES uno uno FR un en (ανάμεσα α και ε) RUS ОДИН [ad`in] TUR bir μπίρ 1 EL Δύο Dio AL Dy Du DE zwei tzwai EN two TUR ES dos dos FR deux de (κλειστό) RU ДВА [dva] TUR iki Ικί 2 EL Τρία tria AL Tre Tre DE drei drai EN three Thri ES tres tres FR trois troua RUS ТРИ [tri] TUR üç uts 3 EL Τέσσερα tesera AL Katër Kater DE vier fiir EN four For ES cuatro kuatro FR quatre katr RUS ЧЕТЫРЕ [chit`iri] TUR dört Ντόρτ 4 EL Πέντε pede AL Pese Pese DE fünf fuenf EN Five Faiv ES cinco thinko FR cinq senk RUS ПЯТЬ [pyat] TUR beş Μπές(παχυ ς) 5 EL Έξι eksi AL Gjashtë Yaste DE sechs zeks EN Six Siks ES Seis seis FR Six sis RUS ШЕСТЬ [shESP’t] TUR ALBtı Αλτί(κλειστο ι) 6 EL Επτά epta AL Shtatë State DE sieben ziiben EN Seven Seven ES siete siete FR sept set RUS СЕМЬ [sem’] TUR Yedi γεντί 7 EL Οκτώ okto AL Tetë Tete DE acht acht EN Eight Eit ES ocho otso FR huit ouit RUS ВОСЕМЬ [v`osim’] TUR sekiz σεκίζ 8 EL Εννέα ennea AL Nëntë Nente DE neun noin EN Nine Nain ES nueve nueve FR neuf ne (κλειστό) f RUS ДЕВЯТЬ [d`evit] TUR dokuz Ντοκούζ 9 EL Δέκα Deka AL Dhjetë Thiete DE zehn tzeen EN Ten Ten ES diez dieth FR dix dis RUS ДЕСЯТЬ [d`ESPit] TUR On On 10 EL Έντεκα edeka AL Njëmbedhjetë niebethiete DE elf elf EN eleven Ileven ES once onthe FR onze onz RUS ОДИННАДЦАТЬ [ad`innadtsat] TUR on bir Ον μπίρ 11 EL Δώδεκα dodeka AL Dymbëdhjetë dubethiete DE zwölf tzwelf EN Twelve Twelv ES doce dothe FR douze douz RUS ДВЕНАДЦАТЬ [dvin`adtsat] TUR on iki Ον ικί 12 EL Δεκατρία dekatria AL Trembedhjetë trebethiete DE dreizehn draitzeen -

The Bullpup Bark

Las Juntas Elementary School Aaron Tarzian, Principal December 5, 2011 Phone: 335-5830 Website: www.LasJuntas.org The Bullpup Bark New Leaf HS students welcomed @ LJE! One of our goals for the past couple of school students in her class have years has been to work on enriching the already visited Las Juntas a number of environmental education of our students times and have been working with our along with increasing the beautification third and fourth grade students on of our campus by creating school some projects related to their field trip gardens. You probably have already to John Muir House. I have to say that I Upcoming Events noticed the planter boxes that have was very impressed by how prepared been slowly multiplying around our and professional these HS students take ♦ Tuesday, 12/6 campus. You may also have noticed the work that they do with our Music performance for that many of them are yet to be used to elementary students! I noticed that classes West, Ellis, their full potential. For this reason, we these HS students take the content McNamer, Stevens, & have been actively seeking support in that they are presenting to the Bauer @ Alhambra High creating school garden beds through a students very seriously and this in turn School number of avenues. You also may caused our students to admire these - 5:40pm – students already know that Heather Hamilton, older students and be incredibly arrive Las Juntas parent, has been taking the engaged in what they are learning! - 6:15pm – auditorium open for parents primary lead on this project with the - 6:30pm – show creation of the Gardening Club this past Next steps for these projects include begins! year; she too has been looking for ways getting the New Leaf students over to You can't miss it!! to get things rolling at LJE.