'Fashions of the Mind': Modernism and British

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion Oana Carmina Cimpean Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion Oana Carmina Cimpean Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Cimpean, Oana Carmina, "Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2283. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2283 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LOUIS ARAGON AND PIERRE DRIEU LA ROCHELLE: SERVILITYAND SUBVERSION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of French Studies by Oana Carmina Cîmpean B.A., University of Bucharest, 2000 M.A., University of Alabama, 2002 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2004 August, 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my dissertation advisor Professor Alexandre Leupin. Over the past six years, Dr. Leupin has always been there offering me either professional advice or helping me through personal matters. Above all, I want to thank him for constantly expecting more from me. Professor Ellis Sandoz has been the best Dean‘s Representative that any graduate student might wish for. I want to thank him for introducing me to Eric Voegelin‘s work and for all his valuable suggestions. -

British Media Kit 2021 British Vogue Is the Authority on Fashion, Beauty and Lifestyle, and Is a Destination for Women to Learn, Be Challenged, Inspired and Empowered

British Media Kit 2021 British Vogue is the authority on fashion, beauty and lifestyle, and is a destination for women to learn, be challenged, inspired and empowered. Under Edward Enninful’s unmatched global editorial status, British Vogue has become the undisputed Fashion Bible in the United Kingdom and is leading the cultural zeitgeist worldwide. 20M 796K TOTAL REACH READERSHIP 190K 14M CIRCULATION SOCIAL FOLLOWERS 6M 72% DIGITAL UNIQUES ABC1 £130K 59% AVERAGE HHI LONDON / SE 95% 87% SEE JEWELLERY AS VALUE TRAVELLING GOOD INVESTMENT ABROAD HIGHLY £7.9K £2.9K AVERAGE ANNUAL AVERAGE ANNUAL SPEND ON FASHION SPEND ON BEAUTY & WELLNESS Sources: ABC Jan-Dec 2020; Pamco 4, 2020; GA Nov-Jan 2020/2021; Conde Nast Luxury Survey 2019; Conde Nast Beauty Survey 2020 2 “Before I got the job I spoke to certain women and they felt they were not represented by the magazine, so I wanted to create a magazine that was open and friendly. A bit like a shop that you are not scared to walk into. You are going to see all different colours, shapes, ages, genders, religions. That I am very excited about.” EDWARD ENNINFUL, OBE BRITISH VOGUE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF & VOGUE’S EUROPEAN EDITORIAL DIRECTOR 3 “I’m excited to assume this highly-coveted role. In a moment when continuous change across the communications, fashion and luxury industries creates dynamic and exhilarating opportunities for the strongest media brands, Vogue’s unrivalled equity sets it apart as the best of the best.” VANESSA KINGORI, MBE BRITISH VOGUE PUBLISHING DIRECTOR 4 BRITISH SOCIETY OF MAGAZINE -

A History of the French in London Liberty, Equality, Opportunity

A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2013. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 48 3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 86 5 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors vii List of figures xv List of tables xxi List of maps xxiii Acknowledgements xxv Introduction The French in London: a study in time and space 1 Martyn Cornick 1. A special case? London’s French Protestants 13 Elizabeth Randall 2. Montagu House, Bloomsbury: a French household in London, 1673–1733 43 Paul Boucher and Tessa Murdoch 3. The novelty of the French émigrés in London in the 1790s 69 Kirsty Carpenter Note on French Catholics in London after 1789 91 4. Courts in exile: Bourbons, Bonapartes and Orléans in London, from George III to Edward VII 99 Philip Mansel 5. The French in London during the 1830s: multidimensional occupancy 129 Máire Cross 6. Introductory exposition: French republicans and communists in exile to 1848 155 Fabrice Bensimon 7. -

Programming Sex, Gender, and Sexuality: Infrastructural Failures in the “Feminist” Dating App Bumble

Programming Sex, Gender, and Sexuality: Infrastructural Failures in the “Feminist” Dating App Bumble Rena Bivens & Anna Shah Hoque Carleton University ABSTRACT Background Bumble is a self-declared “feminist” dating app that gives women control over initiating conversations with potential matches. Analysis Through a material-semiotic analysis of Bumble’s software and online media about the app, this article critically investigates how gender, sex, and sexuality are produced and given meaning by Bumble’s programmed infrastructure. Conclusions and implications Since the epistemological underpinnings of Bumble’s design centre gender as the solitary axis of oppression, the authors argue that the app’s infrastructure generates an ontological relationship between gender, sex, and sexuality that narrows the ca - pacity to achieve its creators’ stated social justice objectives. Several infrastructural failures are detailed to demonstrate how control and safety are 1) optimized for straight cisgender women, and 2) contingent on the inscription of an aggressive form of masculinity onto straight male bodies. Keywords Computer science; Electronic culture (internet-based); Sociotechnical; Feminism/ gender; Technology RÉSUMÉ Contexte Bumble est une application de rencontres prétendument « féministe » qui donne aux femmes le pouvoir d’initier des conversations avec des compagnons potentiels. Analyse Cet article effectue une analyse sémiotique matérielle de Bumble et de commentaires en ligne sur cette application dans le but d’examiner comment l’infrastructure programmée de Bumble produit le genre, le sexe et la sexualité et leur donne du sens. Conclusions et implications Bumble a une perspective épistémologique selon laquelle le genre est la seule source d’oppression. Or, d’après les auteurs, ce point de vue encourage un rapport ontologique entre genre, sexe et sexualité qui entrave la capacité des créateurs à atteindre leurs objectifs de justice sociale. -

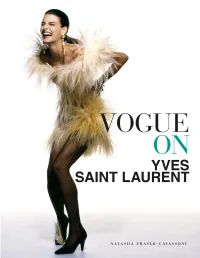

Vogue on Yves Saint Laurent

Model Carrie Nygren in Rive Gauche’s black double-breasted jacket and mid-calf skirt with long- sleeved white blouse; styled by Grace Coddington, photographed by Guy Bourdin, 1975. Linda Evangelista wears an ostrich-feathered couture slip dress inspired by Saint Laurent’s favourite dancer, Zizi Jeanmaire. Photograph by Patrick Demarchelier, 1987. At home in Marrakech, Yves Saint Laurent models his new ready-to-wear line, Rive Gauche Pour Homme. Photograph by Patrick Lichfield, 1969. DIOR’S DAUPHIN FASHION’S NEW GENIUS A STYLE REVOLUTION THE HOUSE THAT YVES AND PIERRE BUILT A GIANT OF COUTURE Index of Searchable Terms References Picture credits Acknowledgments “CHRISTIAN DIOR TAUGHT ME THE ESSENTIAL NOBILITY OF A COUTURIER’S CRAFT.” YVES SAINT LAURENT DIOR’S DAUPHIN n fashion history, Yves Saint Laurent remains the most influential I designer of the latter half of the twentieth century. Not only did he modernize women’s closets—most importantly introducing pants as essentials—but his extraordinary eye and technique allowed every shape and size to wear his clothes. “My job is to work for women,” he said. “Not only mannequins, beautiful women, or rich women. But all women.” True, he dressed the swans, as Truman Capote called the rarefied group of glamorous socialites such as Marella Agnelli and Nan Kempner, and the stars, such as Lauren Bacall and Catherine Deneuve, but he also gave tremendous happiness to his unknown clients across the world. Whatever the occasion, there was always a sense of being able to “count on Yves.” It was small wonder that British Vogue often called him “The Saint” because in his 40-year career women felt protected and almost blessed wearing his designs. -

Vogue Media Kit 2019

MEDIA KIT 2019 EDWARD ENNINFUL OBE A NEW ERA OF BRITISH VOGUE “Before I got the job I spoke to certain women and they felt they were not represented by the magazine, so I wanted to create a magazine that was open and friendly. A bit like a shop that you are not scared to walk into. You are going to see all different colours, shapes, ages, genders, religions. That I am very excited about.” - Editor-In-Chief, Edward Enninful, OBE The first issue under Enninful was The December 2017 issue. VA N E S S A K I N G O R I M B E “I’m excited to assume this highly-coveted role. In a moment when continuous change across the communications; fashion and luxury industries creates dynamic and exhilarating opportunities for the strongest media brands, Vogue’s unrivalled equity sets it apart as the best of the best.” - Publishing Director, Vanessa Kingori, MBE Vanessa is the first new Publishing Director at British Vogue in a quarter of a century. Having begun her tenure in January 2018, she ushers in a new direction in Vogue’s business strategy. BRITISH VOGUE LEADERSHIP TEAM ACHIEVEMENTS & AWARDS 2018 Edward Enninful OBE Vanessa Kingori MBE Goldsmith’s, University of London | University of the Arts London | Honorary Honorary Fellowship Doctorate “Enninful’s trailblazing work on Italian and “The first female publisher in British Vogue’s American Vogue and W Magazine led to his 102 year-long history, Vanessa Kingori MBE is appointment at British Vogue – where he has instrumental to the creative vision and continued to innovate and inspire.” emphasis on diversity -

Platon the New Yorker World-Renowned, Award-Winning Photographer

Platon The New Yorker World-Renowned, Award-Winning Photographer After working for British Vogue for several years, Platon was invited to New York City to work for the late John Kennedy Jr. and his political magazine, George. Shooting portraits for a range of international publications including Rolling Stone, The New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, Esquire, GQ and The Sunday Times Magazine, Platon developed a special relationship with TIME Magazine, producing over 20 covers for them. In 2007, he photographed Russian Premier Vladimir Putin for TIME Magazine's “Person of the Year” cover. This image was awarded 1st prize at the World Press Photo Contest. In 2008, he signed a multi-year contract with The New Yorker. As the staff photographer, he has produced several largescale photo essays, two of which won ASME Awards in 2009 and 2010. Platon's New Yorker portfolios have focused on themes including the U.S Military, portraits of world leaders and the Civil Rights Movement. In 2009, Platon teamed up with Human Rights Watch to help them celebrate those who fight for equality and justice in countries suppressed by political forces. These projects have highlighted human rights defenders from Burma as well as the leaders of the Egyptian revolution. Following his coverage of Burma, Platon photographed Aung San Suu Kyi for the cover of TIME—days after her release from house arrest. In 2011, Platon was honored with a Peabody Award for collaboration on the topic of Russia's Civil Society with The New Yorker magazine and Human Rights Watch. Platon has published four book of his work: Platon’s Republic (Phaidon Press, 2004), a retrospective of his early work; Power (Chronicle, 2011), 100 portraits of the world’s most powerful leaders; China: Through the Looking Glass (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015), in collaboration with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Service (Prestel, 2016), dedicated to the men and women in the United States Military, their physical and psychological wounds, their extraordinary valor, and the fierce emotions that surround those who serve. -

Mercredi 26 Février 2020

ALDE ALDE siècle e au XXI e Éditions originales du XIX alde.fr 209 mercredi 26 février 2020 Éditions originales du XIXe au XXIe siècle 327 325 326 Exposition à la librairie Giraud-Badin 22, rue Guynemer 75006 Paris Tél. 01 45 48 30 58 - Fax 01 45 48 44 00 [email protected] - www.giraud-badin.com du jeudi 20, vendredi 21, lundi 24 et mardi 25 février de 9 h à 13 h et de 14 h à 18 h (jusqu’à 16 h le mardi 25 février) Notices rédigées par Jean Lequoy Exposition publique à l'Hôtel Ambassador le mercredi 26 février de 10 h à 12 h Sommaire Auteurs du XIXe siècle nos 142 à 222 Auteurs du XXe au XXIe siècle nos 223 à 328 Une collection autour de Paul Morand I. Éditions originales nos 223 à 304 II. Éditions illustrées nos 305 à 314 Conditions de vente consultables sur www.alde.fr En couverture, reproduction du n° 233, Karen BLIXEN. Out of Africa. ALDE Maison de ventes spécialisée Livres-Autographes-Monnaies Éditions originales du XIXe au XXIe siècle Vente aux enchères publiques Mercredi 26 février 2020 à 16 h Hôtel Ambassador 16, boulevard Haussmann 75009 Paris Tél. : 01 44 83 40 40 Commissaire-priseur Jérôme Delcamp ALDE Belgique ALDE Philippe Beneut Maison de ventes aux enchères Boulevard Brand Withlock, 149 1, rue de Fleurus 75006 Paris 1200 Woluwe-Saint-Lambert Tél. 01 45 49 09 24 - Fax 01 45 49 09 30 [email protected] - www.alde.be [email protected] - www.alde.fr Tél. -

LGBTQ Timeline of the 21 Century

LGBTQ Timeline of the 21 st Century 2001 Same-sex marriages laws : o Came into effect : The Netherlands (with joint adoption) Civil Union/Registered Partnership laws : o Came into effect : Germany (without adoption until Oct 2004, then with step-adoption only) o Passed : Finland (without joint adoption until May 2009, then with step-adoption) Limited Partnership laws : o Passed and Came into effect : Portugal (without joint adoption) (replaced with marriage in 2010) o Came into effect : Swiss canton of Geneva (without joint adoption) Anti-discrimination legislation : US states of Rhode Island (private sector, gender identity) and Maryland (private sector, sexual orientation) Equalization of age of consent : Albania , Estonia , Liechtenstein and United Kingdom . Repeal of Sodomy laws : US state of Arizona Decriminalisation of homosexuality : the rest of the United Kingdom's territories [citation needed ] Homosexuality no longer an illness : China Marches and Prides : Protesters disrupt the first Pride march in the Serbian city of Belgrade The first memorial in the United States honoring LGBT veterans was dedicated in Desert Memorial Park , Cathedral City, California. [1] Helene Faasen and Anne-Marie Thus , from the Netherlands, became the first two women to legally marry. [2] 2002 Civil Union/Registered Partnership laws : o Passed and Came into effect : Canadian province of Quebec (with joint adoption) o Came into effect : Finland (without joint adoption until May 2009, then with step-adoption) o Passed : Argentinian city of -

Nordstrom Unveils New Fall Fashion Campaign

Nordstrom Unveils New Fall Fashion Campaign August 7, 2017 Retailer showcases fashion through the lens of photographer Max Farago and director Clara Cullen SEATTLE, Aug. 7, 2017 /PRNewswire/ -- Today, Nordstrom, Inc. launched a new national brand campaign shot by photographer Max Farago with video by director Clara Cullen, which celebrates the best of fall fashion. The campaign will debut on August 7 in the U.S. and on September 4 in Canada with print, digital, social, out of home and video components. The campaign vision and concept was developed by Olivia Kim, Vice President of Creative Projects at Nordstrom, who has set the creative tone for the retailer's last five brand campaigns. Kim along with her creative team tapped Farago and Cullen, the husband and wife creative duo favored by the fashion world, to bring their vision to life. The campaign features intimate and honest portraits of models and non-models alike, minimally edited and styled how people really dress to depict a modern and relevant perspective on a high-fashion campaign. The full campaign imagery and videos can be seen at Nordstrom.com/Fall2017. "People are the foundation of Nordstrom," said Kim. "Our customers and employees are at the center of everything we do. They are our friends and our friends-of-friends, and this season we wanted to convey a sense of community and celebrate real people who are doing great and extraordinary things, who inspire us in our everyday lives. "We see the brand campaigns as our opportunity to tell our most fashion-forward story, yet this season we put the focus back on the people. -

Dorothy Todd's Modernist Experiment in British Vogue, 1922 -1926, by Amanda

This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights and duplication or sale of all or part is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for research, private study, criticism/review or educational purposes. Electronic or print copies are for your own personal, non- commercial use and shall not be passed to any other individual. No quotation may be published without proper acknowledgement. For any other use, or to quote extensively from the work, permission must be obtained from the copyright holder/s. “A plea for a renaissance”: Dorothy Todd’s Modernist experiment in British Vogue, 1922 -1926 Figure 1 Amanda Juliet Carrod A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature June 2015 Keele University Abstract This is not a fashion paper: Modernism, Dorothy Todd and British Vogue "Style is thinking."1 In 1922, six years after its initial inception in England, Vogue magazine began to be edited by Dorothy Todd. Her spell in charge of the already renowned magazine, which had begun its life in America in 1892, lasted until only 1926. These years represent somewhat of an anomaly in the flawless history of the world's most famous fashion magazine, and study of the editions from this era reveal a Vogue that few would expect. Dorothy Todd, the most enigmatic and undocumented figure in the history of the magazine and, arguably within the sphere of popular publications in general, used Vogue as the vehicle through which to promote the innovative forms in art and literature that were emerging at the beginning of the twentieth century.