Methods to Market Mario: an Analysis of American and Japanese Preference for Control in Video Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duckduckgo Search Engines Android

Duckduckgo search engines android Continue 1 5.65.0 10.8MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.64.0 10.8MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.63.1 10.78MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.62.0 10.36MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.61.2 10.36MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.60.0 10.35MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.59.1 10.35MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.58.1 10.33MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.57.1 10.31MB DuckduckGo Privacy browser © DuckduckGo. Privacy, simplified. This article is about the search engine. For children's play, see duck, duck, goose. Internet search engine DuckDuckGoScreenshot home page DuckDuckGo on 2018Type search engine siteWeb Unavailable inMultilingualHeadquarters20 Paoli PikePaoli, Pennsylvania, USA Area servedWorldwideOwnerDuck Duck Go, Inc., createdGabriel WeinbergURLduckduckgo.comAlexa rank 158 (October 2020 update) CommercialRegregedSeptember 25, 2008; 12 years ago (2008-09-25) was an Internet search engine that emphasized the privacy of search engines and avoided the filter bubble of personalized search results. DuckDuckGo differs from other search engines by not profiling its users and showing all users the same search results for this search term. The company is based in Paoli, Pennsylvania, in Greater Philadelphia and has 111 employees since October 2020. The name of the company is a reference to the children's game duck, duck, goose. The results of the DuckDuckGo Survey are a compilation of more than 400 sources, including Yahoo! Search BOSS, Wolfram Alpha, Bing, Yandex, own web scanner (DuckDuckBot) and others. It also uses data from crowdsourcing sites, including Wikipedia, to fill in the knowledge panel boxes to the right of the results. -

How Law Made Silicon Valley

Emory Law Journal Volume 63 Issue 3 2014 How Law Made Silicon Valley Anupam Chander Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj Recommended Citation Anupam Chander, How Law Made Silicon Valley, 63 Emory L. J. 639 (2014). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol63/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHANDER GALLEYSPROOFS2 2/17/2014 9:02 AM HOW LAW MADE SILICON VALLEY Anupam Chander* ABSTRACT Explanations for the success of Silicon Valley focus on the confluence of capital and education. In this Article, I put forward a new explanation, one that better elucidates the rise of Silicon Valley as a global trader. Just as nineteenth-century American judges altered the common law in order to subsidize industrial development, American judges and legislators altered the law at the turn of the Millennium to promote the development of Internet enterprise. Europe and Asia, by contrast, imposed strict intermediary liability regimes, inflexible intellectual property rules, and strong privacy constraints, impeding local Internet entrepreneurs. This study challenges the conventional wisdom that holds that strong intellectual property rights undergird innovation. While American law favored both commerce and speech enabled by this new medium, European and Asian jurisdictions attended more to the risks to intellectual property rights holders and, to a lesser extent, ordinary individuals. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Volume XV, Issue 1 February 2021 PERSPECTIVES on TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 1

ISSN 2334-3745 Volume XV, Issue 1 February 2021 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 1 Table of Content Welcome from the Editors...............................................................................................................................1 Articles Bringing Religiosity Back In: Critical Reflection on the Explanation of Western Homegrown Religious Terrorism (Part I)............................................................................................................................................2 by Lorne L. Dawson Dying to Live: The “Love to Death” Narrative Driving the Taliban’s Suicide Bombings............................17 by Atal Ahmadzai The Use of Bay’ah by the Main Salafi-Jihadist Groups..................................................................................39 by Carlos Igualada and Javier Yagüe Counter-Terrorism in the Philippines: Review of Key Issues.......................................................................49 by Ronald U. Mendoza, Rommel Jude G. Ong and Dion Lorenz L. Romano Variations on a Theme? Comparing 4chan, 8kun, and other chans’ Far-right “/pol” Boards....................65 by Stephane J. Baele, Lewys Brace, and Travis G. Coan Research Notes Climate Change—Terrorism Nexus? A Preliminary Review/Analysis of the Literature...................................81 by Jeremiah O. Asaka Inventory of 200+ Institutions and Centres in the Field of Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism Research.....93 by Reinier Bergema and Olivia Kearney Resources Counterterrorism Bookshelf: Eight Books -

MEDIATING SCANDAL in CONTEMPORARY JAPAN Igor

French Journal For Media Research – n° 7/2017 – ISSN 2264-4733 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ MEDIATING SCANDAL IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN Igor Prusa PhD The University of Tokyo, Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies1 [email protected] Abstract Cet article aborde des traits essentiels des affaires médiatiques dans le Japon contemporain. Il s'agit d'une étude interdisciplinaire qui enrichit non seulement le discours des sciences de médias et du journalisme, mais aussi la pholologie japonaise. L’inspiration théorique s'appuie sur la conception néo-fonctionnaliste du scandale en tant que performance sociale située à la limite du « rituel » (la conduite expressive à la motivation socioculturelle) et de la « stratégie » (une action stratégique délibéreée). La première partie de cette étude est consacrée aux caractéristiques du journalisme politique et du contexte médiatico-politique du Japon d’après-guerre. La seconde partie analyse le procès du scandale médiatique lui-même et quelques techniques ritualisées des organisations médiatiques japonaises. Mots-clés Médias japonais, pratiques de journalisme, affaire médiatique, rituel médiatique, procès de la scandalisation Abstract This paper investigates the main features of media scandal in contemporary Japan. This is important because it can add a fresh interdisciplinary direction in the fields of media studies, journalism, and Japanese philology. Furthermore, the sources from the mainstream media, semi-mainstream tabloids and foreign press were examined vie the lens of contemporary neofunctionalist theory, where scandal is approached as a social performance between ritual (motivated expressive behavior) and strategy (conscious strategic action). Moreover, this research illuminates the logic behind the scandal mediation process in Japan, including the performances of both the journalists and the non-media actors, who become decisive for the development of every media scandal. -

Pure Software in an Impure World? WINNY, Japan's First P2P Case

20 U. OF PENNSYLVANIA EAST ASIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 8 ! ! ! ! [This Page Intentionally Left Blank.] ! Pure Software in an Impure World? WINNY, Japan’s First P2P Case Ridwan Khan* “Even the purest technology has to live in an impure world.”1 In 2011, Japan’s Supreme Court decided its first contributory infringement peer-to-peer case, involving Isamu Kaneko and his popular file-sharing program, Winny. This program was used in Japan to distribute many copyrighted works, including movies, video games, and music. At the district court level, Kaneko was found guilty of contributory infringement, fined 1.5 million yen, and sentenced to one year in prison. However, the Osaka High Court reversed the district court and found for Kaneko. The High Court decision was then affirmed by the Supreme Court, which settled on a contributory infringement standard based on fault, similar to the standard announced by the United States Supreme Court in MGM Studios * The author would like to thank Professor David Shipley of the University of Georgia for his guidance in preparing this article. He would also like to thank Professor Paul Heald of the University of Illinois College of Law for additional help. Finally, the author expresses gratitude to Shinya Nochioka of the Ministry of Finance and Yuuka Kawazoe of Osaka Jogakuin for their friendship and advice on Japanese legal matters and language through the two years spent researching and writing this article. All mistakes, however, are the responsibility of the author. All translations of Japanese language materials into English are by the author. 1 Benjamin Wallace, The Rise and Fall of Bitcoin, WIRED MAGAZINE (Nov. -

Capcom's Monster Hunter Freedom 2 Receives Grand Award Press

September 25th, 2007 Press Release 3-1-3, Uchihiranomachi, Chuo-ku Osaka, 540-0037, Japan Capcom Co., Ltd. Haruhiro Tsujimoto, President and COO (Code No. 9697 Tokyo - Osaka Stock Exchange) Capcom’s Monster Hunter Freedom 2 receives Grand Award - Capcom titles receive most awards of any maker at the Japan Game Awards: 2007 - We at Capcom are proud to announce that “Monster Hunter Freedom 2” has received the esteemed Grand Award as well as the Award for Excellence at the “Japan Game Awards: 2007”. The awards program is sponsored by the Computer Entertainment Software Association for the recognition of outstanding titles in computer entertainment software. The awards ceremony was held at this year’s Tokyo Game Show which took place from September 20-23. “Monster Hunter Freedom 2” is a ‘hunting action’ game that puts the player in the role of a fearless hunter roaming a great expansive world tracking down gigantic fearsome beasts. Players can tackle the adventure alone or join friends over ad-hoc mode for team cooperative action. Since its release, Monster Hunter Freedom 2 has become an extremely popular PSP® title boasting sales of over 1,400,000 copies in Japan since its release in February of this year (as of September 21, 2007). We are also very proud to announce our newest title in the “Monster Hunter” series, “Monster Hunter Portable 2G”. With this title, we will continue to endeavor to bring this exciting series to the ever-increasing audience of Japanese Monster Hunter fans. In addition to “Okami”, “Lost Planet Extreme Condition”, which sold more than a million copies in U.S. -

Subculture As Social Knowledge: a Hopeful Reading of Otaku Culture

DE GRUYTER Contemporary Japan 2016; 28(1): 33–57 Open Access Brett Hack* Subculture as social knowledge: a hopeful reading of otaku culture DOI 10.1515/cj-2016-0003 Abstract: This essay analyzes Japan’s otaku subculture using Hirokazu Miya- zaki’s (2006) definition of hope as a “reorientation of knowledge.” Erosion of postwar social systems has tended to instill a sense of hopelessness among many Japanese youth. Hopelessness manifests as two analogous kinds of refus- al: individual social withdrawal and recourse to solipsistic neonationalist ideol- ogy. Previous analyses of otaku have demonstrated its connections with these two reactions. Here, I interrogate otaku culture’s relationship to neonationalism by investigating its interaction with the xenophobic online subculture known as the netto uyoku. Characterizing both subcultures as discursive practices, I argue that the similarity between netto uyoku and otaku is not one of identity but one of method. Netto uyoku discourse serves to perform an imagined na- tionalist persona. While otaku elements can be incorporated into netto uyoku performance, other net users invoke the otaku faculty of parody to highlight the constructed nature of netto uyoku identity through ironic recontextualiza- tion. This application of otaku principles enables a description of otaku culture as a form of social knowledge, reoriented here to defuse the climate of hope- lessness purveyed by the netto uyoku. In the final section, I offer examples of subcultural knowledge being applied to national and international issues in order to indicate its further potential as a source of enabling hope for Japanese youth. Keywords: otaku, subculture, nationalism, Internet, media studies, Japanese studies, cultural studies 1 Introduction This essay investigates social orientations within Japanese subcultures accord- ing to anthropologist Hirokazu Miyazaki’s (2006: 160) definition of hope as a * Corresponding author: Brett Hack, Aichi Prefectural University, E-mail: [email protected] © 2016 Brett Hack, licensee De Gruyter. -

09062299296 Omnislashv5

09062299296 omnislashv5 1,800php all in DVDs 1,000php HD to HD 500php 100 titles PSP GAMES Title Region Size (MB) 1 Ace Combat X: Skies of Deception USA 1121 2 Aces of War EUR 488 3 Activision Hits Remixed USA 278 4 Aedis Eclipse Generation of Chaos USA 622 5 After Burner Black Falcon USA 427 6 Alien Syndrome USA 453 7 Ape Academy 2 EUR 1032 8 Ape Escape Academy USA 389 9 Ape Escape on the Loose USA 749 10 Armored Core: Formula Front – Extreme Battle USA 815 11 Arthur and the Minimoys EUR 1796 12 Asphalt Urban GT2 EUR 884 13 Asterix And Obelix XXL 2 EUR 1112 14 Astonishia Story USA 116 15 ATV Offroad Fury USA 882 16 ATV Offroad Fury Pro USA 550 17 Avatar The Last Airbender USA 135 18 Battlezone USA 906 19 B-Boy EUR 1776 20 Bigs, The USA 499 21 Blade Dancer Lineage of Light USA 389 22 Bleach: Heat the Soul JAP 301 23 Bleach: Heat the Soul 2 JAP 651 24 Bleach: Heat the Soul 3 JAP 799 25 Bleach: Heat the Soul 4 JAP 825 26 Bliss Island USA 193 27 Blitz Overtime USA 1379 28 Bomberman USA 110 29 Bomberman: Panic Bomber JAP 61 30 Bounty Hounds USA 1147 31 Brave Story: New Traveler USA 193 32 Breath of Fire III EUR 403 33 Brooktown High USA 1292 34 Brothers in Arms D-Day USA 1455 35 Brunswick Bowling USA 120 36 Bubble Bobble Evolution USA 625 37 Burnout Dominator USA 691 38 Burnout Legends USA 489 39 Bust a Move DeLuxe USA 70 40 Cabela's African Safari USA 905 41 Cabela's Dangerous Hunts USA 426 42 Call of Duty Roads to Victory USA 641 43 Capcom Classics Collection Remixed USA 572 44 Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded USA 633 45 Capcom Puzzle -

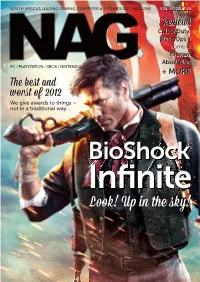

Bioshock Infinite

SOUTH AFRICA’S LEADING GAMING, COMPUTER & TECHNOLOGY MAGAZINE VOL 15 ISSUE 10 Reviews Call of Duty: Black Ops II ZombiU Hitman: Absolution PC / PLAYSTATION / XBOX / NINTENDO + MORE The best and wors t of 2012 We give awards to things – not in a traditional way… BioShock Infi nite Loo k! Up in the sky! Editor Michael “RedTide“ James [email protected] Contents Features Assistant editor 24 THE BEST AND WORST OF 2012 Geoff “GeometriX“ Burrows Regulars We like to think we’re totally non-conformist, 8 Ed’s Note maaaaan. Screw the corporations. Maaaaan, etc. So Staff writer 10 Inbox when we do a “Best of [Year X]” list, we like to do it Dane “Barkskin “ Remendes our way. Here are the best, the worst, the weirdest 14 Bytes and, most importantly, the most memorable of all our Contributing editor 41 home_coded gaming experiences in 2012. Here’s to 2013 being an Lauren “Guardi3n “ Das Neves 62 Everything else equally memorable year in gaming! Technical writer Neo “ShockG“ Sibeko Opinion 34 BIOSHOCK INFINITE International correspondent How do you take one of the most infl uential, most Miktar “Miktar” Dracon 14 I, Gamer evocative experiences of this generation and make 16 The Game Stalker it even more so? You take to the skies, of course. Contributors 18 The Indie Investigator Miktar’s played a few hours of Irrational’s BioShock Rodain “Nandrew” Joubert 20 Miktar’s Meanderings Infi nite, and it’s left him breathless – but fi lled with Walt “Shryke” Pretorius 67 Hardwired beautiful, descriptive words. Go read them. Miklós “Mikit0707 “ Szecsei 82 Game Over Pippa -

Positioning and Face Work on 4Chanâ•Žs /R9k

Syracuse University SURFACE Theses - ALL June 2019 Positioning and Face Work on 4chan’s /r9k/ Michael Camele Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/thesis Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Camele, Michael, "Positioning and Face Work on 4chan’s /r9k/" (2019). Theses - ALL. 337. https://surface.syr.edu/thesis/337 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT : This thesis uses theories of positioning and politeness to analyze a collection of anonymous discussion board posts gathered from 4chan's ROBOT- 9001 message board. I provide an overview of 4chan's history and review recent literature focused on the website. I then examine how users direct gender-based insults at other users within a set of excerpts taken from the larger collection of posts, finding that users who express opposition to misogyny or sexism are identified by others as feminine through the usage of derogatory and misogynistic insults. Next, I examine a second set of excerpts, demonstrating how a user establishes and maintains her identity across multiple anonymous posts in order to respond to insults directed at her by other users. Finally, I conclude with considerations for further research for research interested in 4chan and anonymous text-based computer mediated communication. Positioning and Face Work on 4chan’s /r9k/ by Michael Camele B.A. University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Thesis Submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Master of Arts in Communication & Rhetorical Studies Syracuse University June 2019 Copyright © Michael Camele, 2019 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements I wouldn't have made it through the past two years without the help, support, and quite a good deal of patience from so many people.