Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colby Alumnus Vol. 60, No. 1: Fall 1970

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Alumnus Colby College Archives 1971 Colby Alumnus Vol. 60, No. 1: Fall 1970 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby Alumnus Vol. 60, No. 1: Fall 1970" (1971). Colby Alumnus. 72. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus/72 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Alumnus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. COLBY COLLEGE LIBRARY Waterville, Maine 0 The Issue Fall 1970 f/111111·111111111g . I ht· \H·tkc11d l11lo11gC'd to J. li1·el)e ancl \f,11\ Bi,ln, .111d \\ould h,t\L t\tll if tile footli.dl 1l·:1m h.tcl llJ"t'l tilt· mo.,l powtilttl Bowdo111 'lf"·'d i11 lll< lll\ a )l':1r. (l L Ill.II I) did.) I he pH·,ide11t t•111t·1 itm .111cl hi., wife were ho1101ecl 011 Colin l'\1g ht. .111d 1c,po11dul ''ith the w.umth, chatm :t11cl wit whith d1.11';1ttc111ccl the 18 \it.ti Bl\.kr )Car� at Colb)- (Pages 1-3) The /5Jul cl11.11 a11it•1·1 .. I'rt�idc11t .Strider, in his tradi tional aclcln·.,� lo f1c.,hmu1 011 tlwi1 f11.,t cl.n 011 c.tmpus. <lb- c m�td ,..-h:1l the tollege "ffu., .111cl \\h.1t <.111 be C\.pectcd of '>tudt•11L-.: i11tl'llcctu:tl ch.tllu1gl. \Oti.tl ad.1ptil1ilit) .•1 rc'>pect fot Colb) ·, hcrit.1gc . -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES Charles K

l1146 CQNGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE DECEMBER 8 Officers of the Supply Corps · Clifton B. Cates Lemuel C. Shepherd~ To Be Commanders Leo D. Hermie . Jr. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Charles K. Phillips To be brigadier generals MONDAY, DECEMBER 8, 1947 Allen .B. Reed, Jr. · Alfred H. Noble Omar T. Pfeiffer Officers of the Dentat Corps Graves B. Erskine William E. Riley The House met at 12 o'clock noon. To Be Commanders Louis E. Woods Merwin H. Silverthorn Franklin A. Hart Ray A. Robinson The Chaplain, Rev. James Shera John P. Jarabak Field Harris Gerald C. Thomas Montgomery, D. D., offered the follow Herman K. Rendtorff William J. Wallace Henry D. Linscott ing prayer: Robert D. Wyckoff Oliver P. Smith Dudley S. Brown Almighty God, our Father, we bring Officers of the line Robert Blake Robert H. Pepper our sins and our virtues into Thy re To Be Lieutenant Commanders William A. Worton William P. T. Hill William T. Clement Andrew E. Creesy vealing light and pray Thee to skill us John L. Hutchinson Ogle W. Price, Jr. Louis R. Jones Leonard E. Rea in those purposes which make for a world Walter F. V. Bennett William E. Hoppe John T. Walker Merritt B. Curtis of love, of contentment and peace. Be James F. Wheeler Robert M. Ross Francis A. Lewis William J. Hagerty The following-named officers for appoint not far away, but continue to create Frederick W. Zigler Harry S. Warren ment in the United States Marine Corps in within us the ·finest conceptions of duty Willard H. Davidson James H. -

Spearhead-Fall-Winter-2019.Pdf

Fall/Winter 2019 SpearheadOFFICIAL PUBLICATION of the 5TH MARINE DIVISION NEWS“Uncommon Valor was a Common Virtue” ASSOCIATION OCTOBER 22 - 25, 2020 71ST ANNUAL REUNION DALLAS, TEXAS Sons of Iwo vets take the helm of FMDA Bruce Hammond and statue in Semper Fi Tom Huffhines, both Memorial Park at the native Texans and sons Marine Corps War of Iwo Jima veterans Museum at Quantico, who previously (Triangle) Va., and served as Association had long worked with presidents and reunion the FMDA. hosts, were selected to Continuing his lead the Fifth Marine father’s work with the Division Association Association, President as president and vice Bruce Hammond said, president, respectively, “It is important that we for the next year. channel our passion, Additionally, move forward and lifetime FMDA mem- President Bruce Hammond and Vice President Tom Huffhines focus on our mission ber, Army helicopter for our Marine veterans.” pilot and Vietnam veteran John Powell volunteered to Vice President John Huffhines agreed and said, host the next FMDA reunion from Oct. 22-25, 2020, in “Communication with the membership, as good and Dallas. as often as possible, is extremely key to its existence. Hammond’s father, Ivan (5th JASCO), hosted the Stronger fundraising ideas and efforts should be the 2016 reunion in San Antonio, Texas, when John Butler main thing on each of our agendas.” was president, and in Houston, Texas, in 2009 when he Hammond graduated from the University of Texas, was president himself. Austin, in 1989 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. Huffhines’ father, John (HS 2/3), hosted the 2006 He worked for 24 years as a well-site drilling-fluids reunion in Irving, Texas, when he was president. -

Closingin.Pdf

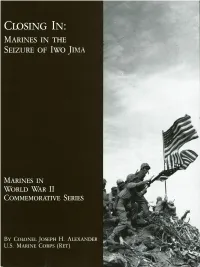

4: . —: : b Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) unday, 4 March 1945,sion had finally captured Hill 382,infiltrators. The Sunday morning at- marked the end of theending its long exposure in "The Am-tacks lacked coordination, reflecting second week ofthe phitheater;' but combat efficiencythe division's collective exhaustion. U.S. invasion of Iwohad fallen to 50 percent. It wouldMost rifle companies were at half- Jima. By thispointdrop another five points by nightfall. strength. The net gain for the day, the the assault elements of the 3d, 4th,On this day the 24th Marines, sup-division reported, was "practically and 5th Marine Divisions were ex-ported by flame tanks, advanced anil." hausted,their combat efficiencytotalof 100 yards,pausingto But the battle was beginning to reduced to dangerously low levels.detonate more than a ton of explo-take its toll on the Japanese garrison The thrilling sight of the Americansives against enemy cave positions inaswell.GeneralTadamichi flag being raised by the 28th Marinesthat sector. The 23d and 25th Ma-Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10rines entered the most difficult ter-had inflicted heavy casualties on the days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphurrain yet encountered, broken groundattacking Marines, yet his own loss- Island." The landing forces of the Vthat limited visibility to only a fewes had been comparable.The Ameri- Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al-feet. can capture of the key hills in the ready sustained 13,000 casualties, in- Along the western flank, the 5thmain defense sector the day before cluding 3,000 dead. -

A Chronology of the UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS 1965

MARINE CORPS HISTORICAL REFERENCE PAMPHLE T A Chronology Of The UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS 1965-1969 VOLUME I V HISTORICAL DIVISION HEADQUARTERS, U . S. MARINE CORP S WASHINGTON, D. C. 1971 HQMC 08JUNO2 ERRATUM to A CHRONOLOGY OF USMC (SFTBOUND ) 1965-1969 1 . Change the distribution PCN read 19000318100 "vice" 19000250200. DISTRIBUTION: PCN 19000318180 PCN 19000318180 A CHRONOLOGY OF THE UNITED STATE S MARINE -CORPS, 1965-196 9 VOLUME I V B Y GABRIELLE M . NEUFEL D Historical Divisio n Headquarters, United States Marine Corp s Washington, D . C . 20380 197 1 PCN 19000318100 DEPARTMENT OF THE NAV Y HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS WASHINGTON . D . C. 20380 Prefac e This is the fourth volume of a chronology of Marin e Corps activities which cover the history of the U . S . Marines . It is derived from unclassified official record s and suitable published contemporary works . This chronology is published for the information o f all interested in Marine Corps activities during the perio d 1965-1969 and is dedicated to those Marines who participate d in the. events listed . J . R . C H Lieute O" General, U . S . Marine Corp s Chief of Staf f Reviewed and approved : 2 September 1971 ABOUT THE AUTHO R Gabrielle M . Neufeld has been a member of the staff o f the Historical Division since January 1969 . At the presen t time she is a historian in the Reference Branch of th e Division . She received her B .A . in history from Mallory College, Rockville Centre, N .Y ., and her M .A . in Easter n history from Georgetown University, Washington, D . -

%E Fftwida !/Late O!Hu~T'1l

A RCH1VES f. S. U. LIBRARY .%e fftwida !/late O!hu~t'1l YatuIJldall1 ~ .A{nth" Jf/~ Yt:nriPed ff+e~t GRADUATION EXERCISES Westcott Auditorium Saturday Afternoon, August Ninth, Three o'Clock PRO CE S SI 0 N AL ____________ __ ______ ________ __________ __ ______________ __ ____ _______ _________ H andel Ramona Cruikshank Beard, Organist INVOCATION _______________ ________ __ ~ ________ ___ _______ __ __ __ ______________ EDWIN R. HARTZ Chaplain, The Florida State University SPECIAL MUSIC "The Shepherd on the Rock" ___________________ __ __________ __ ______ ____ 8chubert Edith Campbell Kaup. Soprano Harry Schmidt, Clarinet Robert Glotzbach, Piano AD D RE S S __ _____________ _______ ___ __ _____________________ ____ ___________ ___ __CHARLES S. D AVIS Dean of the Faculties, The Florida State University CONFERRING OF DEGREES _____ __________ __ __ Robert Manning Strozier President, The Florida State University BE NE D I CTI 0 N ____________ _________ ________________ _____ ____ ______________ ____________ MR. HARTZ RE CESS IONAL ___ __ __ ______ ___ ________ _____ ___________ __ -----___________ _______________ _____ 8 tan ley Mrs. Beard, Organist President and Mrs. Stozier invite the graduates, members of their families, and friends to a reception in the President's Home after the graduation exercises. ACADEMIC REGALIA Three academic degrees are generally recognized: the bachelor, the master, and the doctor. The name of each degree seems to have been determined by medieval university custom. The bachelor's degree, the baccalaureate, takes its name directly from the medieval practice of "bachelors" wearing a garland of bayberries. The master's degree was equivalent to a license to teach, and sometimes was followed by the express words Licentia Docendi. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS November 10, 1993 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

29012 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS November 10, 1993 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS WELFARE REFORM Today, either through ignorance or apathy, sponsored by a Democrat, African-American parents are failing to get their children immu Assemblyman, adopted by New Jersey's HON. MARGE ROUKEMA nized, making these children the victims. The Democratic legislature, and signed into law by OF NEW JERSEY Roukema amendment requires that parents, in a Democratic Governor. The Bush administra IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES order to qualify for AFDC benefits, must have tion gave Federal approval to this provision their children properly immunized and up to last year. This was a key component of New Wednesday, November 10, 1993 date on the vaccinations. My amendment Jersey's pioneering welfare reform package of Mrs. ROUKEMA. Mr. Speaker, I am pleased makes State compliance mandatory. 2 years ago, and garnered national attention. to join with over 150 of my Republican col In addition, our bill requires that day care Perhaps most important, earlier this week, leagues this morning in introducing com and child care centers which receive Federal New Jersey's welfare administration reported prehensive welfare reform legislation. moneys must certify that these same immuni that in the first 2 months of this program, preg The legislation we introduce today address zation requirements are met before enrolling a nancies among welfare mothers decreased 18 es the central crisis of our welfare system; child. percent. This fact alone indicates that these namely, that welfare was intended to be a For generations we have taken this ap provisions must be included in any full-scale temporary safety net-not a perpetual web of proach in requiring immunizations for school reform that comes before the House of Rep dependency. -

![1932-02-28 [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7301/1932-02-28-p-2087301.webp)

1932-02-28 [P ]

SOCIETY SECTION r-.-- -—-1 ^ c \ Features for Capitals Social Women Highlights Part 3—12 Pages -- — — * —-----■-— ----— MRS. ROYAL T. McKENNA, In the costume worn at the George Wash- ington hall at the May- flower, February 22. Harris-EAlhg Photo. REPRESENTATIVE RUTH BRYAN OWEN, MRS. JOHN PHILIP HILL, With her son. Mr. Bryan Owen, and her nephew, Ronald Owen of England, as With her daughters, Miss Susan Hill, Miss Elsie B. Hill they attended the Bicentennial ball. and Miss Catherine Hill, in Colonial ball attire. Harris-Ewing Photo. Underwood Photo. Place Given Mrs. Borah's Niece Cabinet Member Host Enduring Will Arrive Today Bicentennial Week in For Capital Visit For Dean of Diplomats Miss Mary Lueddenan From Memory of Capital City Donna Antoinetta de Martino Asks Secretary Portland, Oreg., Is Guest Lamont to Take Ambassador's at Senator s Home. Ball, Wakefield Pageant and Other PI ace as Mayflower — Host. Events Mark Occasion for Brillia nee. Senator and Mrs. William E. Borah I Costumes Rare Feature. will be joined today by the latter’s Guests invited to the Italian em- The Minister of Honduras, Senor Dr. niece. Miss Mary Lueddenan, who will 4>assy last evening for the dinner given Don Celeo Davila, will be joined tomor- row by Senora de who has been arrive from her home In Portland, Oreg., by the dean of the corps and Donna Davila, BY SALLIE V. H. PICKETT. caxe of Gunston Hall and its landed visiting for several days in Pittsburgh. for a visit. Antoinetta de Martino were grieved to Bicentennial week in Washington and surrounding through a board of regents, find their host a it on the same basis missing, heavy cold The Minister of Bolivia and Senora especially Monday, February 22, must, placing exactly and Mrs. -

Across the Reef: the Marine Assault of Tarawa by Colonel Joseph H

Across the Reef: The Marine Assault of Tarawa by Colonel Joseph H . Alexander, USMC (Ret) n August 1943, to meet momentous . The Tarawa operatio n The Yogaki Plan was the Japanese in secret with Majo r became a tactical watershed: the first , strategy to defend eastern Microne- General Julian C . large-scale test of American amphibi- sia from an Allied invasion . Japanese I Smith and his principal ous doctrine against a strongly for - commanders agreed to counterattac k staff officers of the 2 d tified beachhead . The Marine assault with bombers, submarines, and th e Marine Division, Vice Admiral Ray- on Betio was particularly bloody. Te n main battle fleet . Admiral Chester W. mond A. Spruance, commanding th e days after the assault, Time magazine Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacif- Central Pacific Force, flew to New published the first of many post- ic Fleet/Commander in Chief, Pacifi c Zealand from Pearl Harbor . Spru- battle analyses : Ocean Areas (CinCPac/CinCPOA) , ance told the Marines to prepare fo r took these capabilities seriously. Last week some 2,000 o r an amphibious assault agains t Nimitz directed Spruance to "get th e 3,000 United States Marines, Japanese positions in the Gilbert Is - hell in and get the hell out!" Spruanc e most of them now dead o r lands in November. in turn warned his subordinates t o wounded, gave the nation a The Marines knew about the Gil - seize the target islands in the Gilbert s name to stand beside those o f berts. The 2d Raider Battalion under "with lightning speed ." This sense o f Concord Bridge, the Bon Lieutenant Colonel Evans F. -

F)Llilf . IIIS'i,F)Lly Illlfjjjj\TJ~S

l\1 I'I,NI~SSI~S 'l,f) l\1illl: \Tf)Jfji~S l~llf))J '1,111~ lliJ'I,fJI~IlS f)llilf_. IIIS'I,f)llY illlfjJJJ\TJ~S Image from the Alexander and Bertha Bell Papers, Special Collections & University Archives September 14 to December 31, 2005 Callery '50 Special Collections and University Archives Rutgers University Libraries Rutgers University Libraries RUTGERS WITNESSES TO WAR: VOICES FROM THE RUTGERS ORAL HISTORY ARCHIVES A GUIDE TO THE EXHIBITION Sandra Stewart Holyoak PeterAsch Stephanie Darrell Shaun Illingworth Nicholas Molnar Susan Yousif Curators of the Exhibition Special Collections & University Archives Rutgers University Libraries New Brunswick, New Jersey September 14 - December 23, 2005 - 2- WITNESSES TO WAR: THE USE OF FIRST-PERSON PRIMARY RESOURCES IN THE STUDY OF WORLD WAR II AND THE UNITED STATES, 1989-2005 INTRODUCTION History is lived in instants and revealed in stages. The story of the United States' involvement in the Second World War initially took shape through the pens and lenses of war correspondents and the home front press and the typewriters of government public relations officers. Journalists like Ernie Pyle, Homer Bigart and GI cartoonist Bill Mauldin aspired to transmit the true essence of the war, while the media's lesser lights and the PR men presented a sanitized record draped in patriotic bravado. 1 In the immediate post-war period, the branches of the Armed Forces issued official histories that dealt primarily with battle maneuvers and administrative matters.2 As the surviving luminaries among the Western Allies retired from the military and/or public life in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, they composed (with the assistance of ghostwriters in some cases) and published their memoirs, followed shortly thereafter by their subordinates. -

“Getting Rid of the Line:” Toward an American Infantry Way of Battle, 1918-1945

“GETTING RID OF THE LINE:” TOWARD AN AMERICAN INFANTRY WAY OF BATTLE, 1918-1945 ________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Earl J. Catagnus, Jr. May, 2017 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Gregory J.W. Urwin, Advisory Chair, Department of History Dr. Jay Lockenour, Department of History Dr. Beth Bailey, Department of History Dr. Timothy K Nenninger, National Archives and Records Administration ii © Copyright 2017 By _Earl J. Catagnus, Jr._ All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the development of America’s infantry forces between 1918-1945. While doing so, it challenges and complicates the traditional narrative that highlights the fierceness of the rivalry between the U.S. Army and Marine Corps. During the First World War, both commissioned and enlisted Marines attended U.S. Army schools and served within Army combat formations, which brought the two closer together than ever before. Both services became bonded by a common warfighting paradigm, or way of battle, that centered upon the infantry as the dominant combat arm. All other arms and services were subordinated to the needs and requirements of the infantry. Intelligent initiative, fire and maneuver by the smallest units, penetrating hostile defenses while bypassing strong points, and aggressive, not reckless, leadership were all salient characteristics of that shared infantry way of battle. After World War I, Army and Marine officers constructed similar intellectual proposals concerning the ways to fight the next war. Although there were differences in organizational culture, the two were more alike in their respective values systems than historians have realized. -

War Correspondent and USMC Staff Sgt

War correspondent and USMC Staff Sgt. Solomon Israel Blechman (son of Rabbi Nathan and Esther Blechman of Mamaroneck, NY), was born in New York City on 26 January 1921. His father had worked on the Jewish Welfare Board concerning military hospitals and was also part of the Jewish Theological Seminary, which is the main educational organization for Conservative Judaism. Solomon was raised with an understanding that having a strong military, strong educational institutions and a strong faith community in one’s country was very important. Solomon joined the Marine Corps in the summer of 1942 right after he had graduated from Union College in May. By the summer of 1943, he was promoted to staff sergeant, which was an explosive climb through the ranks (private, private first class, corporal, sergeant, staff sergeant). Many people would require years to do this, yet he did this in a year showing his strength of character and intelligence (also having a college education helped him tremendously). Some clear evidence that this guy was a thinking Marine, as he traveled through the Pacific, along with all his combat gear that he carried to fight the enemy, he also had the following books on his person: “Emerson’s poems,” “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” “Festival Synagogue Service,” “Vanity Fair,” “Mother Russia,” “Marines and Others,” “Tristran Shandy,” “Holy Scriptures for Jewish Soldiers,” and “Jewish Prayer.” He showed that the ultimate weapon is an educated mind and he loved reading (evidenced by the fact he added probably 10-15 pounds of books to his pile of 70 pounds of combat gear that he had to lug around during marches, drills, and deployments).