Methodism Among Nova Scotia's Yankee Planters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fy2019givingreport.Pdf

GLOBAL MISSIONS Fiscal Year 2019 Church Giving Report For the Period 7/1/2018 to 6/30/2019 Name Pastor(s) City State Contribution Pentecostals of Alexandria Anthony Mangun Alex LA $581,066.32 Bethel United Pentecostal Church D. D. Davis, Sr, Doyle Davis, Jr Old Westbury NY $372,979.45 Capital Community Church Raymond Woodward, John Leaman Fredericton NB $357,801.50 The First Church of Pearland Lawrence Gurley Pearland TX $313,976.61 The Pentecostals of Bossier City Jerry Dean Bossier City LA $263,073.38 Eastgate United Pentecostal Church Matthew Tuttle Vidor TX $242,324.60 Calvary Apostolic Church James Stark Westerville OH $229,991.33 First United Pentecostal Church of Toronto Timothy Pickard Toronto ON $222,956.11 United Pentecostal Church of Antioch Gerald Sawyer Ovett MS $183,861.00 Heavenview United Pentecostal Church Harold Linder Winston Salem NC $166,048.10 Calvary Gospel Church Roy Grant Madison WI $162,810.38 Atlanta West Pentecostal Church Darrell Johns Lithia Springs GA $156,756.25 Antioch, The Apostolic Church David Wright, Chester Wright Arnold MD $152,260.00 The Pentecostals of Cooper City Mark Hattabaugh Cooper City FL $151,328.04 Southern Oaks UPC Mark Parker Oklahoma City OK $150,693.98 Apostolic Restoration Church of West Monroe, Inc Nathan Thornton West Monroe LA $145,809.37 First Pentecostal Church Raymond Frazier, T. L. Craft Jackson MS $145,680.64 First Pentecostal Church of Pensacola Brian Kinsey Pensacola FL $144,008.81 The Anchor Church Aaron Bounds Zanesville OH $139,154.89 New Life Christian Center Gary Keller -

The Siege of Fort Beauséjour by Chris M. Hand Notes

1 The Siege of Fort Beauséjour by Chris M. Hand Notes Early Conflict in Nova Scotia 1604-1749. By the end of the 1600’s the area was decidedly French. 1713 Treaty of Utrecht After nearly 25 years of continuous war, France ceded Acadia to Britain. French and English disagreed over what actually made up Acadia. The British claimed all of Acadia, the current province of New Brunswick and parts of the current state of Maine. The French conceded Nova Scotia proper but refused to concede what is now New Brunswick and northern Maine, as well as modern Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton. They also chose to limit British ownership along the Chignecto Isthmus and also harboured ambitions to win back the peninsula and most of the Acadian settlers who, after 1713, became subjects of the British Crown. The defacto frontier lay along the Chignecto Isthmus which separates the Bay of Fundy from the Northumberland Strait on the north. Without the Isthmus and the river system to the west, France’s greatest colony along the St. Lawrence River would be completely cut off from November to April. Chignecto was the halfway house between Quebec and Louisbourg. 1721 Paul Mascarene, British governor of Nova Scotia, suggested that a small fort could be built on the neck with a garrison of 150 men. a) one atthe ridge of land at the Acadian town of Beaubassin (now Fort Lawrence) or b) one more west on the more prominent Beauséjour ridge. This never happened because British were busy fighting Mi’kmaq who were incited and abetted by the French. -

The Boundaries of Nationality in Mid-18Th Century Nova Scotia*

GEOFFREY PLANK The Two Majors Cope: The Boundaries of Nationality in Mid-18th Century Nova Scotia* THE 1750S BEGAN OMINOUSLY IN Nova Scotia. In the spring of 1750 a company of French soldiers constructed a fort in a disputed border region on the northern side of the isthmus of Chignecto. The British built a semi-permanent camp only a few hundred yards away. The two armies faced each other nervously, close enough to smell each other's food. In 1754 a similar situation near the Ohio River led to an imperial war. But the empires were not yet ready for war in 1750, and the stand-off at Chignecto lasted five years. i In the early months of the crisis an incident occurred which illustrates many of *' the problems I want to discuss in this essay. On an autumn day in 1750, someone (the identity of this person remains in dispute) approached the British fort waving a white flag. The person wore a powdered wig and the uniform of a French officer. He carried a sword in a sheath by his side. Captain Edward Howe, the commander of the British garrison, responded to the white flag as an invitation to negotiations and went out to greet the man. Then someone, either the man with the flag or a person behind him, shot and killed Captain Howe. According to three near-contemporary accounts of these events, the man in the officer's uniform was not a Frenchman but a Micmac warrior in disguise. He put on the powdered wig and uniform in order to lure Howe out of his fort. -

Separation of Church and State: a Diffusion of Reason and Religion

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2006 Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion. Patricia Annettee Greenlee East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Greenlee, Patricia Annettee, "Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion." (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2237. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2237 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion _________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University __________________ In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _________________ by Patricia A. Greenlee August, 2006 _________________ Dr. Dale Schmitt, Chair Dr. Elwood Watson Dr. William Burgess Jr. Keywords: Separation of Church and State, Religious Freedom, Enlightenment ABSTRACT Separation of Church and State: A Diffusion of Reason and Religion by Patricia A.Greenlee The evolution of America’s religious liberty was birthed by a separate church and state. As America strides into the twenty first century the origin of separation of church and state continues to be a heated topic of debate. -

BROADSIDES the Programs and Catalogues of Brown

BROADSIDES The programs and catalogues of Brown University are representative of the work of a number of Rhode Island printers, including H.H. Brown (Hugh Hale Brown), Brown and Wilson (Hugh Hale Brown, William H. WIlson), John Carter, Carter and Wilkinson (John Carter, William Wilkinson), Dunham and Hawkins (William H. Dunham, David Hawkins, Jr.), Barnum Field, Field and Maxcy (Barnum Field, Eaton W. Maxcy), Gilbert and Dean ==?== Goddard and Knowles (William G. Goddard, James D. Knowles), Goddard and Mann (William G. Goddard, William M. Mann), J.A. and R.A. Reid (James Allen Reid), Smith and Parmenter (SAmuel J. Smith, Jonathan C. Parmenter); also the Microcosism Office and the American (Rhode Island American?) Office. BR-1F: CATALOGUS Latin catalogue of graduates of the College. The first Catalogus is mentioned in Ezra Stiles' diary. Lists baccalaureate and honorary graduates by year. In later editions, graduates are listed under year alphabetically in two groups, graduates in course and honorary graduates. For the year 1772 only graduates in course appear. At the time of publication of the Historical Catalogue of Brown University, 1764-1894, no copy was known. The copy now in the Archives has been annotated in ink, changing the A.B. after names of 1769 graduates to A.M. Forenames are in Latin form, and in later editions, names of clergy men are in italics, and names of deceased are starred, with a summary at the end. Printed triennially. Second edition in 1775. Evans 16049 and 17347 describe editions of 1778 and 1781, and Alden 756 concludes that these descriptions were by conjecture from the 1775 edition on the assumption that a catalogue was issued every three years, and that no such catalogues were actually printed in those years. -

First Baptist Church in America

First Baptist Church in America Church Profile, 2014 75 North Main Street Providence, RI 02904 401.454.3415 www.fbcia.org Pastoral Leadership The position of Minister of FBCIA is open following the announced retirement, effective February 28, 2014, of Dr. Dan E. Ivins. Dr. Ivins officially became the 36th minister of this church on December 1, 2006. He began first as the interim minister in February of that year, and as the pastoral search committee labored to find a new settled minister, people began to ask, “Why not Dan?” His great sense of humor and his wonderful preaching captured the hearts of everyone. He was near the end of his ministerial career, having served as the interim at another church in Rhode Island before we hired him. First Baptist Church accepted him with the knowledge that he was closing out his active pastoral ministry. He had to be talked into becoming the settled minister, and he agreed to stay at least three years. He remained with us into his eighth year and has retired at age 70. We are now looking for our 37th minister in a line that runs back to Roger Williams in 1638. We are seeking a servant minister who relishes the opportunity to lead this ancient Baptist church which lives in the heart of Providence, which is not a neighborhood church and whose parish is the state. Church Organization The church staff is composed of the Minister, Associate Minister, Minister of Music, an office-manager/secretary, part-time bookkeeper, full-time sexton and, and a Sunday child-care person. -

Birds of the Nova Scotia— New Brunswick Border Region by George F

Birds of the Nova Scotia— New Brunswick border region by George F. Boyer Occasional Paper Number 8 Second edition Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Environnement Canada Wildlife Service Service de la Faune Birds of the Nova Scotia - New Brunswick border region by George F. Boyer With addendum by A. J. Erskine and A. D. Smith Canadian Wildlife Service Occasional Paper Number 8 Second edition Issued under the authority of the Honourable Jack Davis, PC, MP Minister of the Environment John S. Tener, Director Canadian Wildlife Service 5 Information Canada, Ottawa, 1972 Catalogue No. CW69-1/8 First edition 1966 Design: Gottschalk-)-Ash Ltd. 4 George Boyer banding a barn swallow in June 1952. The author George Boyer was born in Woodstock, New Brunswick, on August 24, 1916. He graduated in Forestry from the University of New Brunswick in 1938 and served with the Canadian Army from 1939 to 1945. He joined the Canadian Wildlife Service in 1947, and worked out of the Sackville office until 1956. During that time he obtained an M.S. in zoology from the University of Illinois. He car ried on private research from April 1956 until July 1957, when he rejoined CWS. He worked out of Maple, Ontario, until his death, while on a field trip near Aultsville. While at Sackville, Mr. Boyer worked chiefly on waterfowl of the Nova Scotia-New Brunswick border region, with special emphasis on Pintails and Black Ducks. He also studied merganser- salmon interrelationships on the Miramichi River system, Woodcock, and the effects on bird popu lations of spruce budworm control spraying in the Upsalquitch area. -

View Full Article

ARTICLE CHURCH TAXES AND THE ORIGINAL UNDERSTANDING OF THE ESTABLISHMENT CLAUSE MARK STORSLEE† Since the Supreme Court’s decision in Everson v. Board of Education, it has been widely assumed that the Establishment Clause forbids government from ‘aiding’ or subsidizing religious activity, especially religious schools. This Article suggests that this reading of the Establishment Clause rests on a misunderstanding of Founding-era history, especially the history surrounding church taxes. Contrary to popular belief, the decisive argument against those taxes was not an unqualified assertion that subsidizing religion was prohibited. Rather, the crucial argument was that church taxes were a coerced religious observance: a government-mandated sacrifice to God, a tithe. Understanding that argument helps to explain a striking fact about the Founding era that the no-aid theory has largely ignored—the pervasive funding of religious schools by both the federal government and the recently disestablished states. But it also has important implications for modern law. Most significantly, it suggests that where a funding program serves a public good and does not treat the religious aspect of a beneficiary’s conduct as a basis for funding, it is not an establishment of religion. † Assistant Professor, Penn State Law School; McDonald Distinguished Fellow, Emory University School of Law. Thanks to Gary Adler, Larry Backer, Stephanie Barclay, Thomas Berg, Nathan Chapman, Donald Drakeman, Carl Esbeck, Steven Green, Philip Hamburger, Benjamin Johnson, Elizabeth Katz, Douglas Laycock, Ira Lupu, Jason Mazzone, Michael McConnell, Eugene Volokh, Lael Weinberger, and John Witte, Jr. for valuable conversations and criticisms. Thanks to the McDonald Fellows at Emory Law School and the Constitutional Law Colloquium at the University of Illinois School of Law for helpful workshops, and to Daniel Dicce and Diego Garcia for excellent research assistance. -

The Case of Edward Manning (1767-1851)

From Itinerant to Pastor: The Case of Edward Manning (1767-1851) by Barry Moody Historians have been in general agreement that the roots of the Baptist denomination in the Maritime Provinces lie deep in the Great Awakening. It is felt, however, that by 1800, the Baptist Church had emerged from the chaos and uncertainty of the period of religious upheaval; from the secure footing of the Baptist Association,formed in that year, the denomination would expand and grow, becoming the most dynamic religious force in the Maritimes in the 19th century. Maurice Armstrong, in the last paragraph of his signifi cant study The Great Awakening in Nova Scotia, 1776-1809 summed up well the prevailing view of what took place. He wrote: Ecclesiasticism had triumphed; the cycle of the Great Awakening was completed; the revolt against the "forms of Godliness" was ended, and the Protes tant Dissenters of Nova Scotia, after their brief but spectacular flight, laid aside the wings of the spirit and settled down to orderly and unexciting growth.1 It was not to check the validity of this view but rather to attempt to understand the process that occasioned this paper. How did men, whose early ministerial experience was in the cruci ble of the Great Awakening, eventually make the transition from itinerant preacher to settled pastor of an established church? Just as importantly, how did a group of people, used to the irratic service of an itinerant, transform themselves into a church, complete with . 2 1 doctrine, practice, building, pastor and the resultant respon sibilities? These were the questions that led to the present topic. -

An Assessment of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Availability in Constructed Wetlands in the Cumberland Marsh Region, Canada

An assessment of nitrogen and phosphorus availability in constructed wetlands in the Cumberland Marsh Region, Canada by Maxwell J. Turner Thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science with Honours in Geology Acadia University April, 2016 © Copyright by Maxwell J. Turner 2016 The thesis by Maxwell J. Turner is accepted in its present form by the Department of Earth and Environmental Science as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science with Honours Approved by Thesis Supervisors _____________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Ian Spooner Date _____________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Mark Mallory Date Approved by the Head of the Department _____________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Ian Spooner Date Approved by the Honours Committee ______________________________ _______________________________ Dr. Anna Redden Date ii I, Max Turner, grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to reproduce, loan or distribute copies of my thesis in microform, paper or electronic formats on a non-profit basis. I, however, retain copyright in my thesis. ___________________________________ Maxwell Turner ___________________________________ Date iii Acknowledgements I would like to extend recognition to Acadia University and Ducks Unlimited Canada, whose funding and dedication to scientific research made this project possible. Nic McLellan of Ducks Unlimited provided both in-field help and a useful supply of regional knowledge. I would like to thank the entirety of the Department of Earth and Environmental Science for providing a supportive learning environment that allows one to feel comfortable, acknowledged, and feel the expectation for success; but a special thanks to Dr. Rob Raeside whose subtle acknowledgements truly made me feel that this was the department to which I belonged. -

Nova Scotia Routes

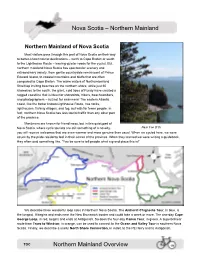

Nova Scotia – Northern Mainland Northern Mainland of Nova Scotia Most visitors pass through this part of Nova Scotia on their way to better-known tourist destinations – north to Cape Breton or south to the Lighthouse Route – leaving quieter roads for the cyclist. But northern mainland Nova Scotia has spectacular scenery and extraordinary variety, from gentle countryside reminiscent of Prince Edward Island, to coastal mountains and bluffs that are often compared to Cape Breton. The warm waters of Northumberland Strait lap inviting beaches on the northern shore, while just 60 kilometres to the south, the giant, cold tides of Fundy have created a rugged coastline that is ideal for shorebirds, hikers, beachcombers, and photographers – but not for swimmers! The eastern Atlantic coast, like the better known Lighthouse Route, has rocks, lighthouses, fishing villages, and fog, but with far fewer people. In fact, northern Nova Scotia has less tourist traffic than any other part of the province. Maritimers are known for friendliness, but in this quiet part of Nova Scotia, where cycle tourists are still something of a novelty, Near Cap D’Or you will receive welcomes that are even warmer and more genuine than usual. When we cycled here, we were struck by the pride residents feel in their corner of the province. When they learned we were writing a guidebook, they often said something like, “You be sure to tell people what a grand place this is!” We describe three wonderful loop rides in Northern Nova Scotia. The Amherst-Chignecto Tour, in blue, is the longest. It begins and ends near the New Brunswick border and could take a week or more. -

Fort Beauséjour National Park Museum CATALOGUE of EXHIBITS

CATALOGUE OF EXHIBITS IN THE Fort Beauséjour National Park Museum CATALOGUE OF EXHIBITS IN THE Fort Beauséjour National Park Museum PREPARED BY J. C. WEBSTER, C.M.G., M.D., D.Sc. LL.D., F.R.S.C. Member of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada HONORARY CURATOR DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND RESOURCES HON. T. A. CRERAR. Minister CHARLES CAMSELL, Deputy Minister LANDS, PARKS AND FORESTS BRANCH R. A. GIBSON, Director NATIONAL PARKS BUREAU F. H. H. WILLIAMSON, Controller OTTAWA, CANADA 43910—U FORT BEAUSËJOUR NATIONAL PARK NEW BRUNSWICK Introduction HE site of old Fort Beauséjour, located on the long ridge between the Aulac and Missaguash rivers, and over Tlooking Chignecto Bay, forms one of the most interest ing historical places in New Brunswick. The fort was originally constructed by the French between 1751 and 1755 on the orders of de la Jonquière, Governor of Canada, as a counter defence against the English Fort Lawrence, which stood on a parallel ridge about a mile and half to the south east. It derived its name from an early settler, Laurent Chatillon, surnamed Beauséjour, after whom the southern end of the ridge had been named Pointe-à-Beauséjour. In 1755, before its actual completion, Fort Beauséjour was attacked by an expedition from Boston under the com mand of Colonel the Honourable Robert Monckton. Landing at the mouth of the Missaguash river, the English force, which numbered about 2,000 New Englanders, encamped at Fort Lawrence before marching on the fort, being joined there by 300 British regulars. Following the capture of an outpost at Pont à Buot, heavy guns and mortars were landed from the boats, gun-emplacements were dug over 800 yards north of the fort, and a heavy fire was opened on the fortifi cations by the batteries.