World Journal of Hepatology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incidence, Risk Factors and Management of Severe Post-Transsphenoidal Epistaxis Q ⇑ Kenneth M

Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 22 (2015) 116–122 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Clinical Neuroscience journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jocn Clinical Study Incidence, risk factors and management of severe post-transsphenoidal epistaxis q ⇑ Kenneth M. De Los Reyes a, Bradley A. Gross a, , Kai U. Frerichs a, Ian F. Dunn a, Ning Lin a, Jordina Rincon-Torroella a, Donald J. Annino b, Edward R. Laws a a Department of Neurological Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA, 02115, USA b Department of Otolaryngology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA article info abstract Article history: Among the major complications of transsphenoidal surgery, less attention has been given to severe post- Received 16 June 2014 operative epistaxis, which can lead to devastating consequences. In this study, we reviewed 551 consec- Accepted 2 July 2014 utive patients treated over a 4 year period by the senior author to evaluate the incidence, risk factors, etiology and management of immediate and delayed post-transsphenoidal epistaxis. Eighteen patients (3.3%) developed significant postoperative epistaxis – six immediately and 12 delayed (mean postoper- Keywords: ative day 10.8). Fourteen patients harbored macroadenomas (78%) and 11 of 18 (61.1%) had complex Endoscopic nasal/sphenoid anatomy. In the immediate epistaxis group, 33% had acute postoperative hypertension. Epistaxis In the delayed group, one had an anterior ethmoidal pseudoaneurysm, and one had restarted anticoagu- Management Microscopic lation on postoperative day 3. We treated the immediate epistaxis group with bedside nasal packing fol- Pituitary lowed by operative re-exploration if conservative measures were unsuccessful. -

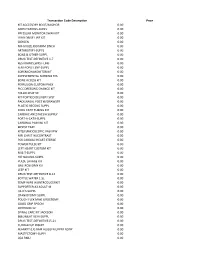

Transaction Code Description

Transaction Code Description Price KIT ACCESSORY BOOT/ANCHOR 0.00 AMPUTATIONS-SUPPL 0.00 PRESSURE MONITOR SWAN KIT 0.00 LVAD DRIVE LINE KIT 0.00 OXYGEN 0.00 NU-GAUZE,IODAFRM 1INCH 0.00 ARTHROTMY-SUPPL 0.00 BONE & OTHER-SUPPL 0.00 DRUG TEST-DEFINITIVE 1-7 0.00 RESTRAINTS,WRST-LMB 0.00 FEM-POPLIT.BYP-SUPPL 0.00 SORENSON MONITOR KIT 0.00 SUPPLEMENTAL NURSING SYS 0.00 BONE ACCESS KIT 0.00 PERFUSION CUSTOM PACK 0.00 PICC DRESSING CHANGE KIT 0.00 FOLLOLWUP 30 0.00 KIT PORTICO DELIVERY SYST 0.00 PACK,NASAL POST W/DRAWSTR 0.00 PLASTIC RECONS-SUPPL 0.00 COOL CATH TUBING KIT 0.00 CARDIAC ANESTHESIA SUPPLY 0.00 PORT-A-CATH-SUPPL 0.00 CARDINAL PAIN INJ KIT 0.00 BIOPSY TRAY 0.00 KIT(LF)ENDOSCOPIC VASVIEW 0.00 MRI CHEST W/CONTRAST 0.00 PCK CARDIAC HEART STERILE 0.00 POWER PULSE KIT 0.00 LEFT HEART CUSTOM KIT 0.00 M & T-SUPPL 0.00 HIP NAILING-SUPPL 0.00 PULSE LAVAGE KIT 0.00 GASTROSTOMY KIT 0.00 LEEP KIT 0.00 DRUG TEST-DEFINITIVE 8-14 0.00 BOTTLE WATER 1.5L 0.00 TEMP WIRE W/INTRODUCERKIT 0.00 SUPPORTER,A3 ADULT-M 0.00 I & D'S-SUPPL 0.00 CRANIOTOMY-SUPPL 0.00 POUCH FLEX MAXI UROSTOMY 0.00 GOOD GRIP SPOON 0.00 OXYHOOD 12- 0.00 SPINAL CARE KIT JACKSON 0.00 BI&UNILAT VEIN-SUPPL 0.00 DRUG TEST-DEFINITIVE15-21 0.00 CUDDLECUP INSERT 0.00 BLANKET (LF) BAIR HUGGER UPPER BODY 0.00 MASTECTOMY-SUPPL 0.00 LOA RMU 0.00 PACK LINQ 0.00 CHOLECYSTECTOM-SUPPL 0.00 RES BWL,SIG,AP-SUPPL 0.00 TRAY BIOPSY GENERAL UTIL 0.00 KIT(LF)CUSTOM SYRINGE ANGIO 0.00 OXISENSOR(LF)PEDI (PINK) 0.00 THORACIC SURG-SUPPL 0.00 NU-GAUZE PLAIN 1/2INCH 0.00 NU-GAUZE,IODAFRM 1/4INCH 0.00 PICC -

Application and Care of Two Kinds of Sphenoid Sinus Packing Materials After Pituitary Tumor Resection with the Transnasal Endoscopic Approach

Neuroscience & Medicine, 2020, 11, 130-141 https://www.scirp.org/journal/nm ISSN Online: 2158-2947 ISSN Print: 2158-2912 Application and Care of Two Kinds of Sphenoid Sinus Packing Materials after Pituitary Tumor Resection with the Transnasal Endoscopic Approach Shuo Yang, Qiyu Feng, Huidan Zhu, Zhihuan Zhou*, Ji Zhang* Department of Neurosurgery, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China How to cite this paper: Yang, S., Feng, Abstract Q.Y., Zhu, H.D., Zhou, Z.H. and Zhang, J. (2020) Application and Care of Two Kinds Background: Neuroendoscopic transsphenoidal approach for resection of of Sphenoid Sinus Packing Materials after pituitary adenomas has the advantages of less damage, fewer complications, Pituitary Tumor Resection with the Trans- and a faster recovery than the traditional approach and has beening favored nasal Endoscopic Approach. Neuroscience by neurosurgeons. However, there has no standard method of selecting suita- & Medicine, 11, 130-141. https://doi.org/10.4236/nm.2020.114015 ble packing materials after the operation to relieve pain in patients and achieve the ideal hemostatic effect. We compared the postoperative complica- Received: October 4, 2020 tions and treatment effects of two different packing materials in patients with Accepted: December 12, 2020 pituitary adenomas. Objective: To investigate the advantages and disadvan- Published: December 15, 2020 tages of using a catheter balloon and iodoform gauze for hemostasis in pa- Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and tients undergoing pituitary tumor resection by neuroendoscopic transsphe- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. noidal approach. Materials and Methods: We retrospectively analyzed these This work is licensed under the Creative data of 48 cases treated with pituitary adenoma resection by the single nasal Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). -

Esophagogastric Tamponade Tube Practice Guideline

Practice Guideline: Esophagogastric Tamponade Tube (EGTT): Assisting with Insertion, Care and Removal CLINICAL Approval Date: Pages: PRACTICE April 28, 2017 1 of 9 GUIDELINE Approved By: Supercedes: Standards Committee N/A Professional Advisory Committee 1. PURPOSE AND INTENT 1.1 To provide guidance and support for the safe insertion, care and maintenance and removal of an Esophagogastric Tamponade Tube (EGTT). Registered Nurses in WRHA Critical Care Units, WRHA Cardiac Sciences, and Emergency Departments may assist with insertion; and provide ongoing care for patients requiring EGTT placement. This guideline is also intended to provide guidance and support to assit the Physician with the insertion of the EGTT. 2. PRACTICE OUTCOME 2.1 Cessation of variceal bleeding and resolution of hypovolemic shock. 3. BACKGROUND 3.1 Esophageal and gastric varices develop because of portal hypertension and vascular congestion. Rupture of the dilated veins may result in gastrointestinal hemorrhage and hypovolemic shock. Without immediate bleeding control, death occurs. Tamponade therapy exerts direct pressure against the varices with a gastric or esophageal balloon and may be used for patients unresponsive to medical therapy (including endoscopic hemostasis and vasoconstrictor therapy) and those too hemodynamically unstable to undergo endoscopy or sclerotherapy. 3.2 Esophagogastric tamponade tubes are used to control bleeding from gastric or esophageal varices. The suction lumens allow the evacuation of accumulated blood from the stomach or esophagus and intermittent instillation of saline to help evacuate blood or clots. Practice Guideline: Esophagogastric Tamponade Tube (EGTT): Assisting with Insertion, Care and Removal CLINICAL Approval Date: Pages: PRACTICE April 28, 2017 2 of 9 GUIDELINE Approved By: Supercedes: Standards Committee N/A Professional Advisory Committee 4. -

Skull Base Defects, Intracranial Complications And

CASE REPORT – OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 4 (2013) 656–661 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect International Journal of Surgery Case Reports j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijscr Traumatic epistaxis: Skull base defects, intracranial complications and neurosurgical considerations Anand Veeravagu, Richard Joseph, Bowen Jiang, Robert M. Lober, Cassie Ludwig, ∗ Roland Torres, Harminder Singh Stanford Hospitals and Clinics, Department of Neurosurgery, 300 Pasteur Drive, R200/MC:5826, Stanford, CA 94305, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: INTRODUCTION: Endonasal procedures may be necessary during management of craniofacial trauma. Received 23 February 2013 When a skull base fracture is present, these procedures carry a high risk of violating the cranial vault and Accepted 10 April 2013 causing brain injury or central nervous system infection. Available online 21 May 2013 PRESENTATION OF CASE: A 52-year-old bicyclist was hit by an automobile at high speed. He sustained extensive maxillofacial fractures, including frontal and sphenoid sinus fractures (Fig. 1). He presented to Keywords: the emergency room with brisk nasopharyngeal hemorrhage, and was intubated for airway protection. Epistaxis He underwent emergent stabilization of his nasal epistaxis by placement of a Foley catheter in his left Foley catheter Intracranial nare and tamponade with the Foley balloon. A six-vessel angiogram showed no evidence of arterial dissection or laceration. Imaging revealed inadvertent insertion of the Foley catheter and deployment Nasogastric tube Skull base fracture of the balloon in the frontal lobe (Fig. 2). The balloon was subsequently deflated and the Foley catheter removed. -

1. CS. Select the Correct Definition of Local Anesthesia. A) Temporary Loss

“CONFIRM” Dean of Medicine Faculty nr.2, MD, docent, M.Beţiu ___//____________// 2014 TESTS for examination in general surgery and semiology (2013-2014 years) 1. CS. Select the correct definition of local anesthesia. a) Temporary loss of consciousness b) Complete irreversible loss of sensation in the region of administration of anesthetic c) Temporary loss of sensation in the region of administration of anesthetic d) Total inhibition of autonomic nervous system e) Partial inhibition of the central nervous system with loss of sensation in some areas of the body 2. CM. Select the stages of local anesthesia. a) Administration of anesthetic substance b) Period of expectation c) Complete anesthesia d) Muscular relaxation e) Recovery of sensation 3. CS. What is an action of the local anesthesia upon the central nervous system? a) No action b) Complete loss of consciousness c) Excitation of the central nervous system d) Inhibition of the central nervous system e) Partial loss of consciousness 4. CM. Select surgical interventions that may be performed under local anesthesia. a) Surgery for purulent tenosynovitis (tendinous felon) b) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy c) Inguinal hernia repair d) Splenectomy e) Excision of benign tumor (lypoma) of the superficial soft tissues 5. CM. To the superficial local anesthesia refer: a) Anesthesia by application b) Anesthesia by spraying c) Anesthesia by instillation d) Regional anesthesia e) Tumescent anesthesia 6. CM. Superficial local anesthesia is more frequently used in: a) Gynecology b) Ophthalmology c) Urology d) Orthopedics e) Neurosurgery 7. CM. Advantages of local anesthesia comparing with general anesthesia are: a) Surgery under local anesthesia may be performed in out-patient conditions (without hospitalization) b) Close postoperative monitoring of the patient is not required c) Local anesthesia can be used if contraindications to general anesthesia exist d) Patients don’t require the prolonged preoperative preparation for anesthesia e) Local anesthesia is not associated with risk of allergic reactions 8. -

Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: a Guide for Midwives and Doctors

Integrated Management Of Pregnancy And Childbirth Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A guide for midwives and doctors Second Edition Integrated Management Of Pregnancy And Childbirth Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A guide for midwives and doctors Second Edition Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors – 2nd ed. ISBN 978-92-4-156549-3 © World Health Organization 2017 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors – 2nd ed. -

Esophagogastric Tamponade Tube

Unit IV Gastrointestinal System Section Sixteen Special Gastrointestinal Procedures PROCEDURE Esophagogastric 108 Tamponade Tube Rosemary Lee PURPOSE: Esophagogastric tamponade therapy is used to provide temporary control of bleeding from gastric or esophageal varices. • Contraindications include latex allergy, esophageal strictures, PREREQUISITE NURSING and recent esophageal surgery. Relative contraindications are KNOWLEDGE heart failure, respiratory failure, hiatal hernia, severe pulmo- nary hypertension, and cardiac dysrhythmias. 4,8,12 • Tamponade therapy exerts direct pressure against the • Because of the risk for aspiration, it is recommended the varices with the use of a gastric and/or esophageal balloon patient be endotracheally intubated for airway protection and may be used for patients who are unresponsive to before esophagogastric tamponade tube insertion. 13 medical therapy or are too hemodynamically unstable for • Sedation should be considered, but dosing should be indi- endoscopy or sclerotherapy. 1,3 vidualized on the assessment of each patient. Sedation • Esophagogastric tamponade tubes are used to control should be used with caution in the setting of liver injury bleeding from either gastric and/or esophageal varices. and/or failure due to these patients ’ impaired metabolism The suction lumens allow the evacuation of accumulated of sedating medications. The plan for sedation, if needed, blood from the stomach or esophagus. The suction lumens is individualized with the goal to achieve patient comfort. also allow for the intermittent instillation of saline solu- • Head of bed (HOB) should be at least 30 to 45 degrees at tion to assist with evacuation of blood or clots and provide all times to reduce the risk of aspiration. 6 a means of irrigation if indicated. -

Effect of Designed Implemented Nurses' Educational Program on Minimizing Incidence of Complications for Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Original Article Egyptian Journal of Health Care, 2015EJHC Vol.6 No.1 Effect of Designed Implemented Nurses' Educational Program on Minimizing Incidence of Complications for Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding ZeinabHosny Ibrahim khalifa*, SanaaMohamed Ahmed A.Eldeen**, HebaAbd El Kader*, FawzyMegahed khalill*** *Medical Surgical Nursing Deprtement, Faculty of Nursing, Benha University ** Adult Nursing Deprtement, Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University *** Internal Medicine Deprtement, Faculty of Medicine, Benha University ABSTRACT The study aimed at assesses the effect of designed implemented nurses' educational program on minimizing incidence of complications for patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. To achieve this aim four research hypothesis were formulated; the nurses' post program mean knowledge scores will be higher than pre-program mean scores, the nurses' post program mean practice scores will be higher than pre-program mean scores, the frequency of patients' complications incidence post- program will be lesser than that of the pre- program and there will be a positive correlation between the nurses' knowledge and practice scores. A sample of (60) adult patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and (30) nurses were involved in this study. The study carried out at Benha University Hospitals at the Internal Medicine Department. Data related to this study were collected by three tools; astructuredinterviewing schedule to assess the nurses’ knowledge, an observation check list to assess the nurses' practice and patients' complications assessment sheet. Theresults implied that: there was plainly improvement in nurses' knowledge and practice score especially immediately post program implementation, as well as, there were significant differences between nurses' knowledge and practice in all study phases,also there was precisely decline in all complications' prevalence among each and every one in post program implementation group, as well there was a positive non-significant correlation between knowledge and practice score. -

(ELSO) Guidelines for Adult Respiratory Failure August, 2017

Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Guidelines for Adult Respiratory Failure August, 2017 Introduction This guideline describes prolonged extracorporeal life support (ECLS, ECMO), applicable to adult patients with respiratory failure. These Guidelines are based on the general Guidelines for all ECMO patients. Anyone undertaking ECMO for adult respiratory failure should be thoroughly familiar with the general guidelines before proceeding to adult respiratory ECMO. The general guidelines are repeated where appropriate. These guidelines describe useful and safe practice, prepared by ELSO and based on extensive experience. The guidelines are approved by the ELSO Steering Committee and are considered consensus guidelines. The guidelines are referenced to the ELSO Red Book which includes evidence based guidelines where available. These guidelines are not intended to define standard of care, and are revised at regular intervals as new information, devices, medications, and techniques become available. The background, rationale, and references for these guidelines are found in “Extracorporeal Life Support: The ELSO Red Book, 5th Edition, 2017” published by ELSO. These guidelines address technology and patient management during ECLS. Equally important issues such as personnel, training, credentialing, resources, follow up, reporting, and quality assurance are addressed in other ELSO documents or are center- specific. The reference is: ELSO Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Extracorporeal Life Support Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, -

Handbook for Brunner and Suddarth's Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing

LWBK397-FM_pi-x.qxd 9/1/09 12:11 PM Page i HANDBOOK FOR BRUNNER & SUDDARTH’S Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing TWELFTH EDITION LWBK397-FM_pi-x.qxd 9/1/09 12:11 PM Page ii Acquisitions Editor: Hilarie Surrena Product Director: Renee Gagliardi Vendor Manager: Cindy Rudy Design Coordinator: Joan Wendt Senior Manufacturing Manager: William Alberti Compositor: Aptara, Inc. 12th Edition Copyright © 2010 by Wolters Kluwer Health / Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2008, 2004, 2000 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews and testing and evaluation materials provided by publisher to instructors whose schools have adopted its accompanying textbook. Printed in the United States of America. For information write Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. Government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. 987654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook for Brunner & Suddarth’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing. —12th ed. p. ; cm. Rev. ed. of: Handbook for Brunner & Suddarth’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing / Joyce Young Johnson. 11th ed. c2008. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-7817-8592-1 1. Nursing—Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Surgical nursing—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Johnson, Joyce Young. -

An Inexpensive Esophageal Balloon Tamponade Trainer

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 53, No. 5, pp. 726–729, 2017 Ó 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.08.018 Techniques and Procedures AN INEXPENSIVE ESOPHAGEAL BALLOON TAMPONADE TRAINER Timothy P. Young, MD, Heather M. Kuntz, MD, Bradley Alice, MD, Jon Roper, MD, and Mike Kiemeney, MD Department of Emergency Medicine, Loma Linda University Medical Center, Loma Linda, California Corresponding Address: Timothy P. Young, MD, Loma Linda University Medical Center, Emergency Medicine, 11234 Anderson Street, A108, Loma Linda, CA 92354 , Abstract—Background: Emergency medicine practi- maneuver when other methods of upper gastrointestinal tioners must be able to perform rare, life-saving procedures. hemorrhage control fail or are unavailable. Major compli- One such example is esophageal balloon tamponade, which is cations of esophageal balloon tamponade devices have complex, fraught with complications, and difficult to demon- been reported, mostly because of inadvertent inflation strate and practice. Discussion: We constructed a simple, in other structures (2–6). This makes opportunities to inexpensive model esophagus and stomach that we attached learn and practice the procedure important. The to a mannequin, allowing emergency medicine residents to visualize and practice esophageal balloon tamponade device mechanics of tube placement are complex and require placement. Conclusion: Our esophageal balloon tamponade that the operator pass the gastric balloon distal to the model was easy to construct and allowed demonstration, esophagus into the stomach, inflate the balloon, then conceptual visualization, and simulated performance of retract the balloon to engage the cardia and fundus of the procedure.