Playing Politics – Warfare in Virtual Worlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manny Diaz LEAD DESIGNER MANNYDIAZDESIGN.COM [email protected] LINKEDIN.COM

Manny Diaz LEAD DESIGNER MANNYDIAZDESIGN.COM [email protected] LINKEDIN.COM Award-Winning Lead Designer with international design development experience including: Design Direction, Design Management, Cross-Studio Collaboration, Mission Design, Scripting, Co-op and Multiplayer Ecosystems, Narrative and Combat Pacing, Chatter Writing, Cinematic Creation, Video Editing, Systems Tuning, Environmental Art, QuickTime Events, Spec Writing, Corporate & Industry Presentations, Film and Game Production Experience Ubisoft Reflections – Lead Level Designer Projects: Watch_Dogs, Tom Clancy’s The Division Time Line: June 2012 – Present Key Achievements: Lead team of 13 designers to deliver next-gen content on time and up to quality Developed implementation best practices for the design team Served as Interim Lead Game Designer Worked with Producers and Directors from co-development studios in Europe, Canada, and US Developed project schedule for design team Selected to represent Ubisoft in an international recruitment video Selected to represent Ubisoft Reflections at TIGA industry event Studio presentations in office and at external venues Video editing for studio presentation Volition Inc. – Design Director, Lead Mission Designer, and Designer 2 Projects: Saints Row: The Third, Saints Row: The Third DLC Packs, Unannounced Next-Gen Project Time Line: February 2010 – June 2012 Key Achievements: Directed three profitable projects to a delivery both on time and on budget Earned multiple awards and positive mentions in press for mission content Generated -

Generation Kill and the New Screen Combat Magdalena Yüksel and Colleen Kennedy-Karpat

15 Generation Kill and the New Screen Combat Magdalena Yüksel and Colleen Kennedy-Karpat No one could accuse the American cultural industries of giving the Iraq War the silent treatment. Between the 24-hour news cycle and fictionalized enter- tainment, war narratives have played a significant and evolving role in the media landscape since the declaration of war in 2003. Iraq War films, on the whole, have failed to impress audiences and critics, with notable exceptions like Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2008), which won the Oscar for Best Picture, and her follow-up Zero Dark Thirty (2012), which tripled its budget in worldwide box office intake.1 Television, however, has fared better as a vehicle for profitable, war-inspired entertainment, which is perhaps best exemplified by the nine seasons of Fox’s 24 (2001–2010). Situated squarely between these two formats lies the television miniseries, combining seriality with the closed narrative of feature filmmaking to bring to the small screen— and, probably more significantly, to the DVD market—a time-limited story that cultivates a broader and deeper narrative development than a single film, yet maintains a coherent thematic and creative agenda. As a pioneer in both the miniseries format and the more nebulous category of quality television, HBO has taken fresh approaches to representing combat as it unfolds in the twenty-first century.2 These innovations build on yet also depart from the precedent set by Band of Brothers (2001), Steven Spielberg’s WWII project that established HBO’s interest in war-themed miniseries, and the subsequent companion project, The Pacific (2010).3 Stylistically, both Band of Brothers and The Pacific depict WWII combat in ways that recall Spielberg’s blockbuster Saving Private Ryan (1998). -

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

25 Jahre Koch Media – Ein Jubiläum (PDF Download)

25 JAHRE KOCH MEDIA - EIN JUBILÄUM Während Unternehmen in manch anderen Branchen mit 25 Und so ist die Entwicklung von Koch Media in den vergange- Jahren noch zu den Newcomern zählen würden, ist diese nen 25 Jahren auch ein Mutmacher: Sie zeigt, dass man mit Zeitspanne in der Entertainment-Branche kaum zu überbli- der Entwicklung und dem Vertrieb von Games auch in und cken. Zu schnell kommen und gehen Trends und mit ihnen aus Deutschland heraus enorm erfolgreich sein kann. häufig auch ganze Unternehmen. Das gilt ganz besonders für die Games-Branche, die zwar seit vielen Jahren stark Koch Media hat sich in den vergangenen 25 Jahren zu einem wächst, deren dynamische Entwicklung aber selbst Bran- integralen Bestandteil der deutschen Games-Branche ent- chen-Urgesteine von Zeit zu Zeit überfordert. Das 25-jähri- wickelt. Als Gründungsmitglied des BIU – Bundesverband ge Jubiläum von Koch Media ist daher ein Meilenstein, der Interaktive Unterhaltungssoftware und mit Dr. Klemens Kun- gar nicht hoch genug geschätzt werden kann. dratitz als aktivem Vorstand des Verbandes hat sich Koch Media immer für die Themen der Branche und die Weiter- Die Erfolgsgeschichte von Koch Media ist auch mit dem entwicklung der gamescom engagiert. Seit vielen Jahren ist Blick auf ihren Entstehungsort einmalig. Die Geschichte der Koch Media Partner von Spiele-Entwicklern in Deutschland deutschen Games-Branche ist sehr wechselhaft, nur wenige wie aktuell von King Art oder hat eigene Studios wie Deep Unternehmen schaffen es über viele Jahre, hier Games zu Silver Fishlabs. Doch darf man das Unternehmen nicht nur entwickeln und zu verlegen. Das Image von Games hat sich auf seine Rolle in Deutschland beschränken: Mit Niederlas- erst in den vergangenen Jahren verbessert und war zuvor sungen in allen europäischen Kernmärkten, in Nordamerika allzu lange von Klischees bestimmt. -

AUDIO BOOKS, MOVIES & MUSIC 3 Quarter 2013 Reinert-Alumni

AUDIO BOOKS, MOVIES & MUSIC 3rd Quarter 2013 Reinert-Alumni Library Audio Books Brown, Daniel, 1951- The boys in the boat : [nine Americans and their epic quest for gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics] / Daniel James Brown. This is the remarkable story of the University of Washington's 1936 eight-oar crew and their epic quest for an Olympic gold medal. The sons of loggers, shipyard workers, and farmers, the boys defeated elite rivals first from eastern and British universities and finally the German crew rowing for Adolf Hitler in the Olympic games in Berlin, 1936. GV791 .B844 2013AB Bradford, Barbara Taylor, 1933- Secrets from the past : a novel / Barbara Taylor Bradford. Moving from the hills above Nice to the canals and romance of Venice and the riot-filled streets of Libya, Secrets From The Past is a moving and emotional story of secrets, survival and love in its many guises. PS3552.R2147 S45 2013AB Deaver, Jeffery. The kill room / Jeffery Deaver. "It was a 'million-dollar bullet,' a sniper shot delivered from over a mile away. Its victim was no ordinary mark: he was a United States citizen, targeted by the United States government, and assassinated in the Bahamas. The nation's most renowned investigator and forensics expert, Lincoln Rhyme, is drafted to investigate. While his partner, Amelia Sachs, traces the victims steps in Manhattan, Rhyme leaves the city to pursue the sniper himself. As details of the case start to emerge, the pair discovers that not all is what it seems. When a deadly, knife-wielding assassin begins systematically eliminating all evidence-- including the witnesses-- Lincoln's investigation turns into a chilling battle of wits against a cold-blooded killer" -- containter. -

Investor Update 01/13/2015 Gamestop Overview

Investor Update 01/13/2015 GameStop Overview EUROPE 331 CANADA stores 1,321 stores UNITED STATES 4,656 stores 421 stores AUSTRALIA/NZ Italy 420 Ireland 50 France 435 Total Stores: 6,729 Germany 260 6,248 Video game stores Nordic 156 481 Technology Brand stores 2 Video Game Brands Platform Overview GameStop maintains a leadership position in the $22.4bn worldwide gaming market 30-34% next-gen console market share (U.S.) 48-52% next-gen software market share (U.S.) Leading retailer in the fast growing digital business (26%+ CAGR from 2011-2013) Unique in-store customer experience Highly successful loyalty program with 40 million global members Game Informer is the #1 digital magazine globally Established buy-sell-trade program drives differentiation from competitors and enhanced profitability 3 GameStop’s Unique Formula Informed Associates Multichannel Vendor Relationships PowerUp Rewards GameInformer Magazine Buy – Sell – Trade 4 Our Strategic Plan Maximize Brick & Mortar Stores . Capture leading market share of new console cycle . Utilize stores to grow digital sales . Apply retail expertise to Tech Brands Build on our Distinct Pre-owned Business . Expand the value assortment to increase sales and gross profit dollars . Gain market share in Value channel Own the Customer . Capitalize on our international loyalty program, now with 40 million members in 14 countries around the world Digital Growth . DLC, Kongregate, Steam wallet, PC Downloads, Console Network cards Disciplined Capital Allocation . Return 100% of our FCF to shareholders through buyback and dividend unless a better opportunity arises 5 We are delivering on our plan… . Digital & Mobile growth . $2.69B of digital receipts and $989M of mobile revenue since 2011 . -

THQ Nordic AB (Publ) Acquires Koch Media

THQ Nordic AB (publ) acquires Koch Media Investor Presentation February 14, 2018 Acquisition rationale AAA intellectual property rights Saints Row and Dead Island Long-term exclusive licence within Games for “Metro” based on books by Dmitry Glukhovsky 4 AAA titles in production including announced Metro Exodus and Dead Island 2 2 AAA studios Deep Silver Volition (Champaign, IL) and Deep Silver Dambuster Studios (Nottingham, UK) #1 Publishing partner in Europe for 50+ companies Complementary business models and entrepreneurial cultural fit Potential revenue synergy and strong platform for further acquisitions EPS accretive acquisition to THQ Nordic shareholders 2 Creating a European player of great scale Internal development studios1 7 3 10 External development studios1 18 8 26 Number of IPs1 91 15 106 Announced 12 5 17 Development projects1 Unannounced 24 9 33 Headcount (internal and external)1 462 1,181 1,643 Net sales 2017 9m, Apr-Dec SEK 426m SEK 2,548m SEK 2,933m2 Adj. EBIT 2017 9m, Apr-Dec SEK 156m SEK 296m3 SEK 505m2,3 1) December 31, 2017. 2) Pro forma. 3) Adjusted for write-downs of SEK 552m. Source: Koch Media, THQ Nordic 3 High level transaction structure THQ Nordic AB (publ) Koch Media Holding GmbH, seller (Sweden) (Germany) Purchase price EUR 91.5m 100% 100% SALEM einhundertste Koch Media GmbH, Operations Holding GmbH operative company (Austria) 100% (Austria) Pre-transaction Transaction Transaction information . Purchase price of EUR 91.5m – EUR 66m in cash paid at closing – EUR 16m in cash paid no later than August 14, 2018 – EUR 9.5m in shares paid no later than June 15, 2018 . -

Download File

Columbia University Graduate School of Arts & Sciences Human Rights Studies Master of Arts Program Natural Resource Control and Indigenous Rights in Bolivia’s Santa Cruz Department: Post-neoliberal Rhetoric and Reality Hannah Howroyd Thesis adviser: Dr. Inga T. Winkler Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts October 2017 ii Acknowledgements: Thank you to the Columbia Global Policy Initiative, with support of The Endevor Foundation, for providing me with the Graduate Global Policy Award. I want to additionally thank my adviser, Dr. Inga T. Winkler, for her assistance and support throughout the thesis process. iii Abstract: In 2006, the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) government led by Evo Morales took power in Bolivia. This government, supported by a pro-indigenous, anti-neoliberal electorate, has espoused indigenous rights and protections against neoliberal development in Bolivia’s national policies and Constitution. Through a case study of Bolivia’s Santa Cruz department, this paper examines Bolivia’s evolving state-social relationship and its increasingly divergent policies on economic development and indigenous rights. Santa Cruz’ marked presence of the transnational soy industry demonstrate the economic, social, and cultural rights challenges of a post- neoliberal, pro-indigenous Bolivia. This research investigates the nexus between transnational agribusiness and the indigenous rights movement in the Bolivian context, and the social movement strategies and response to the MAS’ contradictory -

Video Games and the Mobilization of Anxiety and Desire

PLAYING THE CRISIS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MOBILIZATION OF ANXIETY AND DESIRE BY ROBERT MEJIA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Professor John Nerone Professor Clifford Christians Professor Robert A. Brookey, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT This is a critical cultural and political economic analysis of the video game as an engine of global anxiety and desire. Attempting to move beyond conventional studies of the video game as a thing-in-itself, relatively self-contained as a textual, ludic, or even technological (in the narrow sense of the word) phenomenon, I propose that gaming has come to operate as an epistemological imperative that extends beyond the site of gaming in itself. Play and pleasure have come to affect sites of culture and the structural formation of various populations beyond those conceived of as belonging to conventional gaming populations: the workplace, consumer experiences, education, warfare, and even the practice of politics itself, amongst other domains. Indeed, the central claim of this dissertation is that the video game operates with the same political and cultural gravity as that ascribed to the prison by Michel Foucault. That is, just as the prison operated as the discursive site wherein the disciplinary imaginary was honed, so too does digital play operate as that discursive site wherein the ludic imperative has emerged. To make this claim, I have had to move beyond the conventional theoretical frameworks utilized in the analysis of video games. -

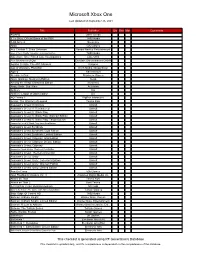

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

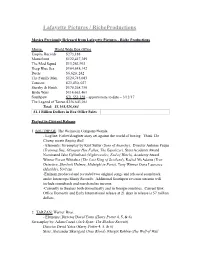

Riche Productions Current Slate

Lafayette Pictures / RicheProductions Movies Previously Released from Lafayette Pictures - Riche Productions Movie World Wide Box Office Empire Records $273,188 Mousehunt $122,417,389 The Mod Squad $13,263,993 Deep Blue Sea $164,648,142 Duets $6,620, 242 The Family Man $124,745,083 Tomcats $23,430, 027 Starsky & Hutch $170,268,750 Bride Wars $114,663,461 Southpaw $71,553,328 - approximate to date – 3/12/17 The Legend of Tarzan $356,643,061 Total: $1,168,526,664 $1.1 Billion Dollars in Box Office Sales Project in Current Release: 1. SOUTHPAW: The Weinstein Company/Wanda - Logline: Father/daughter story set against the world of boxing. Think The Champ meets Raging Bull. - Elements: Screenplay by Kurt Sutter (Sons of Anarchy). Director Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, Olympus Has Fallen, The Equalizer), Stars Academy Award Nominated Jake Gyllenhaal (Nightcrawler, End of Watch), Academy Award Winner Forest Whitaker (The Last King of Scotland), Rachel McAdams (True Detective, Sherlock Holmes, Midnight in Paris), Tony Winner Oona Laurence (Matilda), 50 Cent. -Eminem produced and recorded two original songs and released soundtrack under Interscope/Shady Records. Additional Southpaw revenue streams will include soundtrack and merchandise income. -Currently in theaters both domestically and in foreign countries. Current Box Office Domestic and Early International release at 21 days in release is 57 million dollars. 2. TARZAN: Warner Bros. - Elements: Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Screenplay by: Adam Cozad (Jack Ryan: The Shadow Recruit). Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Stars: Alexander Skarsgard (True Blood), Margot Robbie (The Wolf of Wall Street), Academy Award Nominated Samuel L. -

The Intellectual Functions of Gothic Fiction

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1977 FEARFUL QUESTIONS, FEARFUL ANSWERS: THE INTELLECTUAL FUNCTIONS OF GOTHIC FICTION PAUL LEWIS Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation LEWIS, PAUL, "FEARFUL QUESTIONS, FEARFUL ANSWERS: THE INTELLECTUAL FUNCTIONS OF GOTHIC FICTION" (1977). Doctoral Dissertations. 1160. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1160 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image.