Food (Safety) Policy in the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMMON MARKET SPEEDS up CUSTOM·S UNION Internal Tariff Cuts, Move Toward Common External Tariff Accelerated

JUNE-JULY 1962 N0.54 BELGIUM, FRANCE, GERMAN FEDERAL REPUBLIC, ITALY, LUXEMBOURG, THE NETHERLANDS COMMON MARKET SPEEDS UP CUSTOM·s UNION Internal Tariff Cuts, Move Toward Common External Tariff Accelerated The Common Market has decided to advance still further The new move was "essentially political," said Giuseppe the pace of internal tariff cuts and the move toward a single Caron, vice president of the Common Market Commission. external tariff for the whole European Community. "The maximum length of the transition period in the Treaty Decisions taken by the Council of Ministers on May 15 ( 12-15 years) reflected an understandably cautious attitude put the Community two and a half years ahead of the Rome regarding the ability of the six countries' economies to Treaty schedule. adapt themselves to the new situation, and the speedy On the basis of the Council decision, already decided in adaptation of all sectors of the economy to the challenge principle in April, the Community has made additional in of the new market has enabled us to move ahead more ternal tariff cuts of 10 per cent on industrial goods and of quickly." 5 per cent on some agricultural goods, effective July 1. Signor Caron is chairman of the Common Market com Internal duties on industrial goods thus have been cut to mittee dealing with customs questions. The committee was a total of 50 per cent of the level in force on January 1, set up in April and is composed of the heads of the customs 1957, the base date chosen in the Treaty of Rome. -

![Sicco Mansholt [1908—1995], Duurzaam-Gemeenzaam SICCO ANSHOLT](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7440/sicco-mansholt-1908-1995-duurzaam-gemeenzaam-sicco-ansholt-127440.webp)

Sicco Mansholt [1908—1995], Duurzaam-Gemeenzaam SICCO ANSHOLT

fax. ?W • :•, '•'••• ^5 *4 ffr," Pi Sicco Mansholt [1908—1995], Duurzaam-Gemeenzaam SICCO ANSHOLT, [1908—1995] Duurzaam-Gemeenzaam o Met dank aan Wim Kok, Jozias van Aartsen, Franz Fischler, Louise Fresco, Frans Vera, Riek van der Ploeg, Aart de Zeeuw, Piet Hein Donner, Paul Kalma, Herman Verbeek, Marianne Blom, Cees Van Roessel, Hein Linker, Jan Wiersema, Corrie Vogelaar, Joop de Koeijer, Wim Postema, Jerrie de Hoogh, Gerard Doornbos en Wim Meijer. Redactie Dick de Zeeuw, Jeroen van Dalen en Patrick de Graaf Schilderij omslag Sam Drukker Ontwerp Studio Bau Winkel (Martijn van Overbruggen) Druk Ando bv, 's-Gravenhage Uitgave Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij Directie Voorlichting Bezuidenhoutseweg 73 postbus 20401 2500 EK 's-Gravenhage Fotoverantwoording Foto schilderij omslag, Sylvia Carrilho; Jozias van Aartsen, Directie Voorlichting, LNV; Riek van der Ploeg, Bert Verhoeff; Piet Hein Donner, Hendrikse/Valke; Paul Kalma, Hans van den Boogaard; Herman Verbeek, Voorlichtingsdienst Europees Parlement; Marianne Blom, AXI Press; Gerard Doornbos, Fotobureau Thuring B.V.; Wim Meijer, Sjaak Ramakers s(O o <D o CD i 6 ra ro 3 3 Q CT O O) T 00 o o Inhoud 1 o Herdenken is Vooruitzien u 55 Voorwoord 9 Korte schets van het leven van Sicco Mansholt 13 De visie van Sicco Mansholt Wetenschappelijk inzicht en politieke onmacht 19 Minder is moeilijk in de Europese landbouw 26 Minder blijft moeilijk in de Europese landbouw 54 Een illusie armer, een ervaring rijker 75 Toespraken ter gelegenheid van de Mansholt herdenking Sicco Mansholt, -

Food for the Future

Food for the Future Rotterdam, September 2018 Innovative capacity of the Rotterdam Food Cluster Activities and innovation in the past, the present and the Next Economy Authors Dr N.P. van der Weerdt Prof. dr. F.G. van Oort J. van Haaren Dr E. Braun Dr W. Hulsink Dr E.F.M. Wubben Prof. O. van Kooten Table of contents 3 Foreword 6 Introduction 9 The unique starting position of the Rotterdam Food Cluster 10 A study of innovative capacity 10 Resilience and the importance of the connection to Rotterdam 12 Part 1 Dynamics in the Rotterdam Food Cluster 17 1 The Rotterdam Food Cluster as the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem 18 1.1 The importance of the agribusiness sector to the Netherlands 18 1.2 Innovation in agribusiness and the regional ecosystem 20 1.3 The agribusiness sector in Rotterdam and the surrounding area: the Rotterdam Food Cluster 21 2 Business dynamics in the Rotterdam Food Cluster 22 2.1 Food production 24 2.2 Food processing 26 2.3 Food retailing 27 2.4 A regional comparison 28 3 Conclusions 35 3.1 Follow-up questions 37 Part 2 Food Cluster icons 41 4 The Westland as a dynamic and resilient horticulture cluster: an evolutionary study of the Glass City (Glazen Stad) 42 4.1 Westland’s spatial and geological development 44 4.2 Activities in Westland 53 4.3 Funding for enterprise 75 4.4 Looking back to look ahead 88 5 From Schiedam Jeneverstad to Schiedam Gin City: historic developments in the market, products and business population 93 5.1 The production of (Dutch) jenever 94 5.2 The origin and development of the Dutch jenever -

English, French, Hindi, Japanese, Europe and Central Asia 42 Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish

THE WORLD BANK ANNUAL REPORT 2008 THE WORLD 46256 THE WORLD BANK ANNUAL REPORT 2008 YEAR IN REVIEW YEAR IN REVIEW Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1818 H St NW ISBN 978-0-8213-7675-1 Washington DC 20433 USA THE WORLD BANK Telephone: 202-473-1000 Facsimile: 202-477-6391 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] SKU 17675 THE WORLD BANK OPERATIONAL SUMMARY | FISCAL 2008 ANNUAL REPORT 2008 Offi ce of the Publisher, External Affairs IBRD MILLIONS OF DOLLARS 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 Team Leader Commitments 13,468 12,829 14,135 13,611 11,045 Richard A. B. Crabbe Of which development policy lending 3,967 3,635 4,906 4,264 4,453 Editor Number of projects 99 112 113 118 87 Cathy Lips Of which development policy lending 16 22 21 23 18 Assistant Editor Gross disbursements 10,490 11,055 11,833 9,722 10,109 Belinda Yong Of which development policy lending 3,485 4,096 5,406 3,605 4,348 Editorial Production Principal repayments (including prepayments) 12,610 17,231 13,600 14,809 18,479 Cindy A. Fisher Aziz Gökdemir Net disbursements (2,120) (6,176) (1,767) (5,087) (8,370) Mary C. Fisk Loans outstanding 99,050 97,805 103,004 104,401 109,610 Dina Towbin Undisbursed loans 38,176 35,440 34,938 33,744 32,128 Print Production Randi Park Operating incomea 2,271 1,659 1,740 1,320 1,696 Denise Bergeron Usable capital and reserves 36,888 33,754 33,339 32,072 31,332 Project Assistant Attiya Zaidi Equity-to-loans ratio 38% 35% 33% 31% 29% The World Bank Annual a. -

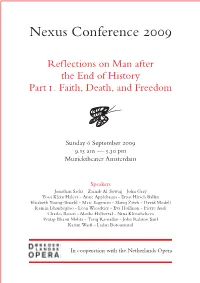

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

1 WITTEVEEN, Hendrikus Johannes (Known As Johan Or Johannes), Dutch Politician and Fifth Managing Director of the International

1 WITTEVEEN, Hendrikus Johannes (known as Johan or Johannes), Dutch politician and fifth Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) 1973-1978, was born 12 June 1921 in Den Dolder and passed away 23 April 2019 in Wassenaar, the Netherlands. He was the son of Willem Gerrit Witteveen, civil engineer and Rotterdam city planner, and Anna Maria Wibaut, leader of a local Sufi centre. On 3 March 1949 he married Liesbeth Ratan de Vries Feijens, piano teacher, with whom he had one daughter and three sons. Source: www.imf.org/external/np/exr/chron/mds.asp Witteveen spent most of his youth in Rotterdam, where his father worked as director of the new office for city planning. His mother was the daughter of a prominent Social-Democrat couple, Floor Wibaut and Mathilde Wibaut-Berdenis van Berlekom, but politically Witteveen’s parents were Liberal. His mother was actively involved in the Dutch Sufi movement, inspired by Inayat Khan, the teacher of Universal Sufism. Sufism emphasizes establishing harmonious human relations through its focus on themes such as love, harmony and beauty. Witteveen felt attracted to Sufism, which helped him to become a more balanced young person. At the age of 18 the leader of the Rotterdam Sufi Centre formally initiated him, which led to his lifelong commitment to, and study of, the Sufi message. After attending public grammar school, the Gymnasium Erasmianum, Witteveen studied economics at the Netherlands School of Economics between 1939 and 1946. The aerial bombardment of Rotterdam by the German air force in May 1940 destroyed the city centre and marked the beginning of the occupation of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany. -

Maes Cover.Indd 1 19/06/2004 22:58:47 EUI Working Paper RSCAS No

EUI WORKING PAPERS RSCAS No. 2004/01 Macroeconomic and Monetary Thought at the European Commission in the 1960s Ivo Maes EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Pierre Werner Chair on European Monetary Union Maes Cover.indd 1 19/06/2004 22:58:47 EUI Working Paper RSCAS No. 2004/01 Ivo Maes, Macroeconomic and Monetary Thought at the European Commission in the 1960s The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies carries out disciplinary and interdisciplinary research in the areas of European integration and public policy in Europe. It hosts the annual European Forum. Details of this and the other research of the centre can be found on: http://www.iue.it/RSCAS/Research/. Research publications take the form of Working Papers, Policy Papers, Distinguished Lectures and books. Most of these are also available on the RSCAS website: http://www.iue.it/RSCAS/Publications/. The EUI and the RSCAS are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES Macroeconomic and Monetary Thought at the European Commission in the 1960s IVO MAES EUI Working Paper RSCAS No. 2004/01 BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO DI FIESOLE (FI) All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing from the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Download and print of the electronic edition for teaching or research non commercial use is permitted on fair use grounds—one readable copy per machine and one printed copy per page. -

Bezinning Op Het Buitenland

Duco Hellema, Mathieu Segers en Jan Rood (red.) Bezinning op het buitenland Het Nederlands buitenlands beleid Zijn de traditionele ijkpunten van het naoorlogse Nederlandse buitenlandse beleid in een onzekere wereld nog up to date? In hoeverre kan het bestaande buitenlandse beleid van Nederland nog gebaseerd worden op de traditionele consensus rond de drie beginselen van (1) trans-Atlantisch veiligheidsbeleid, (2) Europese economische integratie volgens de communautaire methode, en (3) ijveren voor versterking van de internationale (rechts)orde en haar multilaterale instellingen? Is er sprake van een teloorgang van die consensus en verwarring over de nieuwe werkelijkheid? Recente internationale ontwikkelingen op veiligheidspolitiek, economisch, financieel, monetair en institutioneel terrein, als mede op het gebied van mensenrechten en Duco Hellema, Mathieu Segers en Jan Rood (red.) ontwikkelingssamenwerking, dagen uit tot een herbezinning op de kernwaarden en uitgangspunten van het Nederlandse buitenlandse beleid. Het lijkt daarbij urgent een dergelijke herbezinning nu eens niet louter ‘van buiten naar binnen’, maar ook andersom vorm te geven. Het gaat derhalve niet alleen om de vraag wat de veranderingen in de wereld voor gevolgen (moeten) hebben voor het Nederlandse buitenlands beleid. Ook dient nagegaan te worden in hoeverre de Nederlandse perceptie van de eigen rol in de internationale politiek (nog) adequaat is. In verlengde hiervan zijn meer historische vragen te stellen. In hoeverre is daadwerkelijk sprake van constanten in het -

Annual Review 2012 Deltares

ANNUAL REVIEW 2012 ANNUAL Deltares P.O. Box 177 2600 MH Delft The Netherlands DELTARES 2012 T +31 (0)88 335 8273 [email protected] Annual Review www.deltares.nl Follow Deltares www.twitter.com/deltares www.linkedin.com/company/217430 Omslag_buiten_en.indd 1 15-04-13 13:57 DELTARES credits DELTARES, APRIL 2013 A great deal of care has gone into the production of this publication. Use of the texts or parts thereof is permitted on condition that the source is quoted. Re-use of the infor- Our mission mation shall be for the responsibility of the user. ADDRESS Developing and applying top-level expertise Deltares P.O. Box 177 in the field of water, subsurface and 2600 MH Delft www.deltares.nl infrastructure for people, environment and society. Deltares is thereby independent, EDITING Deltares communications department sets high demands on the quality of the [email protected] knowledge and advice and works closely IMAGES with governments, businesses and research Deltares, cover, pages 4, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, institutes at home and abroad. At Deltares, 21, 23, 28, 29, 30, 31, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 42, 54, 55, 56 Dirk Hol, pages 3, 6, 10, 11, 14, 18, 20, 22, 26, 30, knowledge is the key. 32/33, 47, 48, 49, 50, 56 Ewout Staartjes, pages 14, 22, 28 Hans Roode, page 25 Mennobart van Eerden, Rijkswaterstaat, page 24 Rijkswaterstaat, page 8 Stichting Noordzee, page 13 The photos on pages 6, 10, 18, 26, 32/33, 47 and 49 were taken in the Deltares Facilities Hall in Delft. -

Het Hof Van Brussel of Hoe Europa Nederland Overneemt

Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt Arendo Joustra bron Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt. Ooievaar, Amsterdam 2000 (2de druk) Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/jous008hofv01_01/colofon.php © 2016 dbnl / Arendo Joustra 5 Voor mijn vader Sj. Joustra (1921-1996) Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt 6 ‘Het hele recht, het hele idee van een eenwordend Europa, wordt gedragen door een leger mensen dat op zoek is naar een volgende bestemming, die het blijkbaar niet in zichzelf heeft kunnen vinden, of in de liefde. Het leger offert zich moedwillig op aan dit traagkruipende monster zonder zich af te vragen waar het vandaan komt, en nog wezenlijker, of het wel bestaat.’ Oscar van den Boogaard, Fremdkörper (1991) Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt 9 Inleiding - Aan het hof van Brussel Het verhaal over de Europese Unie begint in Brussel. Want de hoofdstad van België is tevens de zetel van de voornaamste Europese instellingen. Feitelijk is Brussel de ongekroonde hoofdstad van de Europese superstaat. Hier komt de wetgeving vandaan waaraan in de vijftien lidstaten van de Europese Unie niets meer kan worden veranderd. Dat is wennen voor de nationale hoofdsteden en regeringscentra als het Binnenhof in Den Haag. Het spel om de macht speelt zich immers niet langer uitsluitend af in de vertrouwde omgeving van de Ridderzaal. Het is verschoven naar Brussel. Vrijwel ongemerkt hebben diplomaten en Europese functionarissen de macht op het Binnenhof veroverd en besturen zij in alle stilte, ongezien en ongecontroleerd, vanuit Brussel de ‘deelstaat’ Nederland. -

Download (123Kb)

Hoofdstuk 1 Een kwestie van mentaliteit Een wijze van zijn De politieke bewustwording van Cees Veerman begon bij een lantaarnpaal in Nieuw-Beijerland. Toen zijn interesse voor politiek ontwaakte, eind jaren vijftig, wees zijn vader hem op een chu-verkiezingsaffiche aan deze paal. ‘Jongen, dat zijn wij’, zei de oude Veerman. Wellicht meer nog dan een politieke unie, en zeker meer dan een partij, was de chu een politieke familie, met haar eigen gebruiken en gewoontes, eigenaardig- heden en ongeschreven codes. Intuïtief bracht vader Veerman onder woorden wat de De Savornin Lohmanstichting in 1958 als het onderscheidende kenmerk van de Christelijk-Historische Unie aanwees.1 Het fundament van de chu was niet zozeer een uitgewerkt politiek gedachtegoed, meende de stichting, maar ‘een wijze van zijn’, volgens oudgediende Johan van Hulst zelfs een ‘unieke wijze van zijn’. Ruim vijftig jaar nadat hij aan de hand van zijn vader voor het eerst kennismaakte met de chu, merkte Veerman hoe hij in zijn opereren als minister van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Voedselkwaliteit nog altijd terugviel op de christelijk-historische familiegebruiken. Hoewel dat oude, traditionele gebruiken waren, vloeide er een heel eigen zienswijze uit voort op de werking van de democratie en de politieke omgangsvormen die in deze tijd wellicht van pas kan komen om het Nederlandse politieke bestel beter te laten functioneren. Dat zal in de loop van dit verhaal blijken. De manier waarop de chu-familieleden in het leven stonden, wortelde in de ontstaansgrond van de Unie: het conflict met de antirevolutionairen van Abraham Kuyper over de mogelijkheid Gods wil in een politiek programma tot uitdrukking te brengen. -

Boer Lonkt Naar VVD, Sterk LNV Én Naar Cees Veerman

MENS EN MENING MENS EN MENING a d v i e s a d v i e s Boeren willen Cees Veerman terug als minister Heel veel agrariërs zien Cees Veerman (CDA) graag terug op het politieke toneel, en wel Boer lonkt naar VVD, sterk op de post van minister van LNV. AgriDirect vroeg de agrariërs wie zij het liefst als LNV- minister willen hebben in het nieuwe kabi- net. Veerman wint met een grote overmacht. Maar liefst 26,6 procent van de deelnemers LNV én naar Cees Veerman aan de Verkiezingspeiling wil Veerman terug op Landbouw. Met veruit de meeste stem- men ‘wint’ hij het van de nummer twee: Joop Het ministerie van Landbouw moet blijven. En Cees Veerman moet terug op de ministerspost. Het CDA mag Atsma – 8,9 procent van de boeren ziet hem het liefst als minister van LNV. nog altijd rekenen op grote aanhang onder agrariërs, maar voor hoe lang nog. De VVD wil die van oudsher Boerenzoon Cees Veerman studeerde econo- ‘boerenpartij’ voorbij. En dat laatste lijkt aardig te lukken. Dit zijn een paar conclusies uit de ‘Verkiezings- mie aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam en promoveerde later aan de Landbouw- peiling 2010’ van agrarisch Direct Marketing bureau AgriDirect en V-focus. universiteit Wageningen op het proefschrift Grond en grondprijs. Vanaf 22 juli 2002 was hij minster van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Geesje Rotgers oeren zijn van oudsher behoor- van Nederland. En in Brabant wordt traditioneel Visserij in het kabinet Balkenende I en ver- lijk CDA-gezind. De partij blijft het vaakst op het CDA gestemd (zie grafiek 3).