Does Substrate Colour Affect the Visual Appearance of Gilded Medieval Sculptures? Part I: Colorimetry and Interferometric Microscopy of Gilded Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gilding Arts Newsletter

The Gilding Arts Newsletter ...an educational resource for Gold Leaf Gilding CHARLES DOUGLAS GILDING STUDIO Seattle, WA February 8, 2020 Quick Links Gilding Arts Newsletter Quiz! Quick Links And the Winner from the Workshop Registration Form (for January Klimt Question is... mail-in registration only) Congratulations to Gilding Arts Newsletter member A Gilder's Journal Tatyana from Texas for submitting the first correct (Blog) answer to last issue's Klimt Quiz! Tatyana's beautiful Georgian Bay Art artwork and photography can be seen here on Conservation Instagram. The quiz question asked what materials were used to Gilding Studio...on Twitter create some of the raised swirling design Uffizi Gallery elements on Klimt's mural Beethoven Frieze Galleria and what other metal dell'Accademia di Firenze was used in the makeup Portrait of of the gold leaf? Adele Bloch-Bauer I Frye Art Museum Seattle Art Museum As outlined in a paper by Alexandra Matzner for the International Institute for Conservation of Historic Society of Gilders and Artistic Works and based upon conservation treatment of this particular work by Klimt, his areas Metropolitan Museum of Relief were comprised of Chalk and animal glue, of Art the same material we often refer to as Pastiglia, or The Fricke Collection Raised Gesso (Chalk being a form of Calcium Carbonate). The gold leaf was shown to consist of 5% Palace of Versailles copper with the remainder gold. Museo Thyssen- During my recent visit in January to the Neue Galerie Bornemisza during the Winter Quarter Gilding Week I once again studied Gustav Sepp Leaf Products Klimt's Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, which also exhibits raised gilded design Gilded Planet elements that are likely the same or a similar approach to Join our list the pastiglia technique where gesso is slowly dripped or drawn in a heavy deposit to create a raised effect. -

Metals and Metal Products Tariff Schedules of the United States

251 SCHEDULE 6. - METALS AND METAL PRODUCTS TARIFF SCHEDULES OF THE UNITED STATES SCHEDULE 6. - METALS AND METAL PRODUCTS 252 Part 1 - Metal-Bearing Ores and Other Metal-Bearing Schedule 6 headnotes: Materials 1, This schedule does not cover — Part 2 Metals, Their Alloys, and Their Basic Shapes and Forms (II chemical elements (except thorium and uranium) and isotopes which are usefully radioactive (see A. Precious Metals part I3B of schedule 4); B. Iron or Steel (II) the alkali metals. I.e., cesium, lithium, potas C. Copper sium, rubidium, and sodium (see part 2A of sched D. Aluminum ule 4); or E. Nickel (lii) certain articles and parts thereof, of metal, F. Tin provided for in schedule 7 and elsewhere. G. Lead 2. For the purposes of the tariff schedules, unless the H. Zinc context requires otherwise — J. Beryllium, Columbium, Germanium, Hafnium, (a) the term "precious metal" embraces gold, silver, Indium, Magnesium, Molybdenum, Rhenium, platinum and other metals of the platinum group (iridium, Tantalum, Titanium, Tungsten, Uranium, osmium, palladium, rhodium, and ruthenium), and precious- and Zirconium metaI a Iloys; K, Other Base Metals (b) the term "base metal" embraces aluminum, antimony, arsenic, barium, beryllium, bismuth, boron, cadmium, calcium, chromium, cobalt, columbium, copper, gallium, germanium, Part 3 Metal Products hafnium, indium, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, A. Metallic Containers molybdenum, nickel, rhenium, the rare-earth metals (Including B. Wire Cordage; Wire Screen, Netting and scandium and yttrium), selenium, silicon, strontium, tantalum, Fencing; Bale Ties tellurium, thallium, thorium, tin, titanium, tungsten, urani C. Metal Leaf and FoU; Metallics um, vanadium, zinc, and zirconium, and base-metal alloys; D, Nails, Screws, Bolts, and Other Fasteners; (c) the term "meta I" embraces precious metals, base Locks, Builders' Hardware; Furniture, metals, and their alloys; and Luggage, and Saddlery Hardware (d) in determining which of two or more equally specific provisions for articles "of iron or steel", "of copper", E. -

Gilding Through the Ages

Gilding Through the Ages AN OUTLINE HISTORY OF THE PROCESS IN THE OLD WORLD Andrew Oddy Research Laboratory, The British Museum, London, U.K. In 1845, Sir Edward Thomason wrote in his not public concern but technological advance which memoirs (1) a description of a visit he had made in brought an end to the use of amalgam for gilding. to certain artisans in Paris and he commented: 1814 Gilding with Gold Foil `I was surprised, however, at their secret of superior Although fire-gilding had been in widespread use in gilding of the time-pieces. I was admitted into one gilding establishment, and I found the medium was Europe and Asia for at least 1 500 years when it was similar to ours, mercury; nevertheless the French did displaced by electroplating, the origins of gilding — gild the large ornaments and figures of the chimney- that is, the application of a layer of gold to the surface piece clocks with one-half the gold we could at of a less rare metal — go back at least 5 000 years, to Birmingham, and produced a more even and finer the beginning of the third millennium B.C. The colour'. British Museum has some silver nails from the site of Much to his disgust, Thomason could not persuade Tell Brak in Northern Syria (5) which have had their the French workmen to tell him the secret of their heads gilded by wrapping gold foil over the silver. superior technique, but it seems most likely that it This is, in fact, the earliest form of gilding and it lay either in the preparation of the metal surface depends not on a physical or chemical bond between for gilding or perhaps in the final cleaning and the gold foil and the substrate, but merely on the burnishing of the gilded surface. -

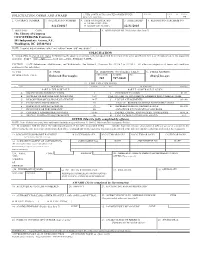

FEDLINK Preservation Basic Services Ordering

SOLICITATION, OFFER AND AWARD 1. THIS CONTRACT IS A RATED ORDER UNDER RATING PAGE OF PAGES DPAS (15 CFR 700) 1 115 2. CONTRACT NUMBER 3. SOLICITATION NUMBER 4. TYPE OF SOLICITATION 5. DATE ISSUED 6. REQUISITION/PURCHASE NO. G SEALED BID (IFB) S-LC04017 G NEGOTIATED (RFP) 12/31/2003 7. ISSUED BY CODE 8. ADDRESS OFFER TO (If other than Item 7) The Library of Congress OCGM/FEDLINK Contracts 101 Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC 20540-9414 NOTE: In sealed bid solicitations “offer” and “offeror” mean “bid” and “bidder” SOLICITATION 9. Sealed offers in original and copies for furnishing the supplies or services in the Schedu.le will be received at the place specified in Item 8, or if handcarried, in the depository located in Item 7 until __2pm______ local time __Tues., February 4, 2004_. CAUTION -- LATE Submissions, Modifications, and Withdrawals: See Section L, Provision No. 52.214-7 or 52.215-1. All offers are subject to all terms and conditions contained in this solicitation. 10. FOR A. NAME B. TELEPHONE (NO COLLECT CALLS) C. E-MAIL ADDRESS INFORMATION CALL: Deborah Burroughs AREA CODE NUMBER EXT. [email protected] 202 707-0460 11. TABLE OF CONTENTS ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) PART I - THE SCHEDULE PART II - CONTRACT CLAUSES A SOLICITATION/CONTRACT FORM 1 I CONTRACT CLAUSES 91-97 B SUPPLIES OR SERVICES AND PRICE/COST 3-23 PART III - LIST OF DOCUMENTS, EXHIBITS AND OTHER ATTACH. C DESCRIPTION/SPECS./WORK STATEMENT 24-77 J LIST OF ATTACHMENTS 98-100 D PACKAGING AND MARKING 78 PART IV - REPRESENTATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS E INSPECTION AND ACCEPTANCE 79 K REPRESENTATIONS, CERTIFICATIONS 101-108 F DELIVERIES OR PERFORMANCE 80 AND OTHER STATEMENTS OF OFFERORS G CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION DATA 81-89 L INSTRS., CONDS., AND NOTICES TO OFFERORS 109-114 H SPECIAL CONTRACT REQUIREMENTS 90 M EVALUATION FACTORS FOR AWARD 115 OFFER (Must be fully completed by offeror) NOTE: Item 12 does not apply if the solicitation includes the provisions at 52.214-16, Minimum Bid Acceptance Period. -

Gold in Mosaic Art and Technique Gianfranco Bustacchini Academy of Fine Arts, Ravenna, Italy

Gold in Mosaic Art and Technique Gianfranco Bustacchini Academy of Fine Arts, Ravenna, Italy One of the most remarkable and fascinating uses of gold is in the art of mosaic. This most lovely and permanent , form of decoration gives both an extraordinary splendour and yet a simplicity of dramatic quality in its representations. This article reviews both the develop- ment of the art of mosaic and the technical processes behind the achievement of the characteristic effects of richness and brilliance. Mosaic work is as ancient as any other art form, Asclepiades of Arado, or similar to those in the although its technique, in becoming ever more Pompeii villa said to have belonged to Cicero. complex and exacting, represents an artistic expres- The material most favoured by the Romans was sion which is not spontaneous but indicative of a derived from limestone, this being easier to handle highly cultured environment, so that anyone who, than volcanic rock such as granite or porphyry. To when confronted by a brilliant Byzantine mosaic, intensify the colouring, these marbles were subjected naively believed it to be the outcome of a single to varying degrees of heat, or were tinted with culture would be totally mistaken. solutions based on colour pigments. Vitreous materials In 2500 B.c. the Sumerians were already covering were seldom used and gold appeared even more walls and columns with decorative motifs composed rarely, especially in floor mosaics. of tiny clay cones the bases of which, projecting from Under the Romans, mosaic work, even if originat- the wall, were glazed or rather dyed by an encaustic ing from different schools, acquired a rather standard- process. -

Royal Gold: Reflections of Power

Podcast transcript Royal Gold: Reflections of Power The Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace Wednesday, 17 December 2014 Kathryn Jones, Senior Curator of Decorative Art, Royal Collection Trust Hello, and welcome to a podcast from Royal Collection Trust where we’ll be looking at how gold has for centuries been associated with royalty. Traditionally it has been used to create the regalia and other trappings associated with coronations, yet surprisingly few items in the Royal Collection are made from solid gold. Coming up, Kathryn Jones, Curator of Decorative Arts at Royal Collection Trust, gives a lecture entitled, ‘Royal Gold: Reflections of Power’ at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace. She will examine a few of these works of art in detail and explore how gold has been used to denote the highest degree of status and authority. This is an enhanced podcast so you’ll be able to see the images being spoken about on the screen of your device. [00:48] Kathryn Jones: Good afternoon everyone. A German visiting Windsor Castle in 1598 recorded that ‘The walls of the Palace shine with gold and silver’ and noted a cabinet where ‘Besides everything glitters so with silver, gold and jewels as to dazzle one’s eyes’. In 1517 Henry VIII held a great banquet at Whitehall for the Ambassadors of France and the Venetian Republic where a great buffet was placed beside the dining table. The display included silver and gold vases worth vast treasure and larger vases of silver gilt. After the banquet the plate was deliberately left on show so that the public could come and view it. -

FRAMING SUPPLY CATALOG OMEGA CANADA Telephone: 1-877-452-3799 Or: 905-452-3799905-856-4343 Fax: 1-877-452-3783 Or: 905-452-3783905-856-4349 Terms & Conditions

QUALITY FRAMING PRODUCTS FOAM BOARD 1 GLASS, ACRYLIC, MIRROR 4 TAPES, ADHESIVES, & MOUNTING SUPPLIES 7 CONSERVATION TAPES, ADHESIVES 10 MOUNTING TISSUES & ADHESIVE RELEASE BOARDS 12 GLUE & ADHESIVES 15 WIRE PRODUCTS 17 BLADES - MAT CUTTING & GENERAL USE 19 V-NAILS 21 JOINING, POINT DRIVERS, STAPLERS & POINTS 22 PICTURE HANGING HARDWARE & FASTENERS 25 TOUCH-UP & FILLERS 34 FITTING & BACKING SUPPLIES 36 MOUNTING & HANGING SUPPLIES 38 SPECIALTY TOOLS & CLEANING ITEMS 40 KRAFT PAPER & DISPENSERS 44 GALLERY HANGING & DISPLAY PRODUCTS 45 PACKING MATERIALS & SUPPLIES 46 STRETCHER BARS 48 EDUCATIONAL MEDIA 49 MACHINERY 51 MATBOARD 69 INDEX 95 FRAMING SUPPLY CATALOG OMEGA CANADA Telephone: 1-877-452-3799 or: 905-452-3799905-856-4343 Fax: 1-877-452-3783 or: 905-452-3783905-856-4349 Terms & Conditions TERMS: • Net 15 days. • Prices subject to change without notice. • Questions concerning your orders should be addressed to us in writing within 10 days of receipt of order. • All past due accounts will be shipped C.O.D. • Shipper’s C.O.D. charge will be added to all C.O.D shipments. • Interest charges of 1.5% will be added to all past due accounts. • There is a $30.00 charge on all NSF checks. • In the event of default of payment, the customer shall pay for all costs of collection, including but not limited to, attorney's fees, court costs, and collection agency fees. CREDIT: • To open your account, please complete our credit application with three trade references and your bank information. Allow 2 to 4 weeks processing to establish an approved credit line. Incomplete credit applications will delay establishment of credit line. -

Stanford White's Frames by William Adair

~ s _es he architect Stanford White has been called the great- Pl. I. Angel, by Abbott Handerson I Thayer(l849-1921), c. 1889, in a frame est designer Ame,;ca has ever produced. In addition designed by Stanford White to buildings he delighted in designing picttu-e frames (1853-1906) and made by Joseph Cabus, New York City, 1889. Gilded for many o[ hi s clients and fri ends, including the composition and wood; outside pa inters Abbott Handerson Thayer and Thomas din1ensions of frame, 66 l/4 by 481/s inches. National Museum of American Wilmer D ewing, and the sculptor Augustus Saint- Art, Washington, D.C., gift ofJolin Gaudens (see Fig. 1). White's frame designs were not only in Gellatly. flu ential in the art world of his time but continue to be so today. Above: Pl. II. Detail of the frame shown in Pl. IX. The chief role of the picture frame is to be an adroit mediator Right: Pl. m. Detail of a frame designed between the illusionary painting and the environment in which by White, c. 1892, and probably made the painting is placed, and it is most successful when it is not by Alexander G. Cabus, New York City, for 11,e Blue Dress, by Thomas Wilmer noticed. White understood this basic prerequisite. His genius Dewing(l851-1938), 1892. Oil-gilded was to combine disparat e elements of the many nineteenth-cen composition on pine; outside din1en sions, 383/4 by 343/4 inches over-all. The te a new vocabulary of frame design tury revival styles to crea gently sloping reverse profile of the (see Pl. -

Silver and Gold Coating

Copyright © Tarek Kakhia. All rights reserved. http://tarek.kakhia.org Gold & Silver Coatings By A . T . Kakhia 1 Copyright © Tarek Kakhia. All rights reserved. http://tarek.kakhia.org 2 Copyright © Tarek Kakhia. All rights reserved. http://tarek.kakhia.org Part One General Knowledge 3 Copyright © Tarek Kakhia. All rights reserved. http://tarek.kakhia.org 4 Copyright © Tarek Kakhia. All rights reserved. http://tarek.kakhia.org Aqua Regia ( Royal Acid ) Freshly prepared aqua regia is colorless, Freshly prepared aqua but it turns orange within seconds. Here, regia to remove metal fresh aqua regia has been added to these salt deposits. NMR tubes to remove all traces of organic material. Contents 1 Introduction 2 Applications 3 Chemistry 3.1 Dissolving gold 3.2 Dissolving platinum 3.3 Reaction with tin 3.4 Decomposition of aqua regia 4 History 1 - Introduction Aqua regia ( Latin and Ancient Italian , lit. "royal water"), aqua regis ( Latin, lit. "king's water") , or nitro – hydro chloric acid is a highly corrosive mixture of acids, a fuming yellow or red solution. The mixture is formed by freshly mixing concentrated nitric acid and hydro chloric acid , optimally in a volume ratio of 1:3. It was named 5 Copyright © Tarek Kakhia. All rights reserved. http://tarek.kakhia.org so because it can dissolve the so - called royal or noble metals, gold and platinum. However, titanium, iridium, ruthenium, tantalum, osmium, rhodium and a few other metals are capable of with standing its corrosive properties. IUPAC name Nitric acid hydro chloride Other names aqua regia , Nitro hydrochloric acid Molecular formula HNO3 + 3 H Cl Red , yellow or gold Appearance fuming liquid 3 Density 1.01–1.21 g / cm Melting point − 42 °C Boiling point 108 °C Solubility in water miscible in water Vapor pressure 21 mbar 2 – Applications Aqua regia is primarily used to produce chloro auric acid, the electrolyte in the Wohl will process. -

Foil and Leaf Gilding on Cultural Artifacts; Forming and Adhesion E

Revista Matéria, v. 16, n. 1, pp. 540 –559, 2011 ISSN 1517-7076 http://www.materia.coppe.ufrj.br/sarra/artigos/artigo11439 Foil and leaf gilding on cultural artifacts; forming and adhesion E. Darque-Ceretti I, Eric Felder I, Marc Aucouturier II I MINES Paristech-CEMEF, Centre de Mise en Forme des Matériaux, CNRS UMR 7635, BP 207, F-06904 Sophia-Antipolis, France. e-mails: [email protected] ; [email protected] II Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France, CNRS UMR 171, Palais du Louvre, porte des Lions, 14 quai François Mitterrand, F-75001 Paris France. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The process used to obtain foils of more and more thin thickness and coat them on artefacts varied during centuries. It started from thick foils of the first ages mechanically assembled and evolved until the rolled and beaten leaves, a few hundred nanometres thick. This paper will develop, through examples taken from laboratory studies on museum objects, the main evolution steps of gold leaf forming. It will discuss the present knowledge about processes used by hand-workers of different origins and periods: antic Egypt, Roman Empire, western and oriental Middle-Age, South America, modern Europe. A recent mechanical modelling work about gold forming by beating will be exposed. Then will be described, still through recent examples, some of the non-destructive and destructive laboratory methods used to characterise ancient and modern gildings, their composition, thickness and adhesion modes. The different coating process will be discussed, owing to the presently available knowledge. -

Techniques for Emulating Textiles: Gold and Its Alternatives

Samuel H. Kress Reconstruction Project TECHNIQUES FOR EMULATING TEXTILES: GOLD AND ITS ALTERNATIVES Lesson Plan 16-Adult From left to right: Giotto, Madonna and Child, tempera and gold on panel, ca. 1320-1330 (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC); Taddeo di Bartolo, Madonna and Child, tempera and gold on panel, 1410 (Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa). Summary Throughout the ages, artists have come up with a variety of techniques to emulate the elaborate designs and embellishments found on textiles worn by religious and civic figures of great importance. These costly fabrics often incorporated gold threads and designs. Painters often used gold leaf or simulated gold threads found on expensive fabrics with illusionistic painting techniques. Examples of the use of gold leaf can be found in Giotto’s Madonna and Child, The Creation of Eve by Maestro Bartolomé, and Madonna and Child by Taddeo di Bartolo. In this lesson participants will learn to recreate these textiles using mordant gilding and sgraffito. These techniques will also be contrasted with approaches used by northern oil painters of the 15th and 16th centuries. Samuel H. Kress Reconstruction Project Age group: 16 to adult. Length of lesson: 3 lessons (300 minutes total). Objectives: • Introduce the students to the Kress Collection. • Deepen the student’s understanding of how Old Masters emulated textiles. • Enable creative exploration and discovery. Materials: • A projector. • A screen. • Black chalk or 4B pencils for each participant. • A metal stylus for each participant. • Two 8x8 in. prepared wooden panels (purchased with ground already applied) for each student. See the section on ground preparation on this website if you wish to prepare the ground yourself. -

Japanese Lacquer

l?o^a,l fl^iq-j-ic. SooeVcj 3^ujrr>gxl 120 REVIEWS OF BOOKS Japanese lacquer. By Ann YONEMURA. pp. 106, 8 pi. Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1979. This attractive booklet is the catalogue of an exhibition held in conjunction with "Japan today". The exhibition covered the range of Japanese lacquer held in the Freer Gallery, much of it coming from the Mosle collection. It gets off to a good start by including a piece of dry lacquer sculpture, of the Nara period, and a lacquered wood sculpture of the Kamalcura period. This is an unusual feature and warmly to be welcomed: normally such catalogues are solely concerned with so-called "applied art" objects. And at the end, the catalogue includes lacquer repairs to ceramics, a similarly unusual inclusion and equally to be welcomed, if with a twinge of doubt about the possibility of dating such repairs. The catalogue continues with negoro, kamakura-hori , and a fine box in Kodaiji style. A particularly interesting piece is the chest of drawers in a version of the Kodaiji style. Ms. Yonemura places this, reasonably, in the beginning of the 17th century for the form is not a little influenced by European shapes and it is probably contemporary with the namhau pieces at the changeover period from the downward-folding tlap door to the outward-folding pair of doors. This is a fine example of the end of the style. Another oddity is the folding table with a top in mmhan style. Unfortunately the description is not adequate for the reader to know whether or not to agree with Yonemura's attribution to the Meiji period.