Stanford White's Frames by William Adair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Law Section Chair Mitchell Y

NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Family Law Section Chair Mitchell Y. Cohen, Esq. Johnson & Cohen LLP White Plains Program Co-Chairs Rosalia Baiamonte, Esq. Gassman Baiamonte Gruner, P.C. Garden City NYSBA Dylan S. Mitchell, Esq. Blank Rome LLP New York City Family Law Section Peter R. Stambleck, Esq. Aronson Mayefsky & Sloan, LLP Summer Meeting New York City Family Law Section The Newport Marriott Hotel CLE Committee Co-Chairs Rosalia Baiamonte, Esq. 25 Americas Cup Ave. Gassman Baiamonte Gruner, PC Garden City Newport, RI Henry S. Berman, Esq. Berman Frucco Gouz Mitchel & Schub PC July 13–16, 2017 White Plains Charles P. Inclima, Esq. Inclima Law Firm, PLLC Rochester Peter R. Stambleck, Esq. Aronson Mayefsky & Sloan, LLP New York City Under New York’s MCLE rule, this program may qualify for UP Bruce J. Wagner, Esq. TO 6.5 MCLE credits hours in Areas of Professional Practice. This McNamee, Lochner, Titus & program is not transitional and is not suitable for MCLE credit for Williams, P.C. newly-admitted attorneys. Albany SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Thursday, July 13 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m. Officers Meeting 12:00 p.m. Registration and Exhibits — South Foyer 2:00 p.m. – 4:30 p.m. Executive Committee Meeting — Salons II, III, IV 6:00 p.m. – 10:00 p.m. Kid’s Dinner & Activities — Portsmouth Room 6:15 p.m. Shuttle will leave for the reception/dinner at the Newport Yachting Center (Bohlin); The shuttle will run a continuous loop 6:30 p.m. – 9:30 p.m. Reception and lobster bake at the Newport Yachting Center (Bohlin) Friday, July 14 7:30 a.m. -

GORHAM BUILDING, 390 Fifth Avenue, Aka 386-390 Fifth Avenue and 2-6 West 36Th Street, Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission December 15, 1998, Designation List 300 LP-2027 GORHAM BUILDING, 390 Fifth Avenue, aka 386-390 Fifth Avenue and 2-6 West 36th Street, Manhattan. Built 1904-1906; architect Stanford White of McKim, Mead and White. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 837, Lot 48. On September 15, 1998, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Gorham Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Seven witnesses representing Manhattan Community Board 5, the Murray Hill Association, the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the Beaux Arts Alliance, the Society for the Architecture of the City, the Municipal Art Society, and the Historic Districts Council spoke in favor of designation. The owner of the building submitted a letter asking that the hearing be adjourned to another date. The hearing was closed with the proviso that it could be reopened at a later date if the owner wished to testify. The owner subsequently declined to do so. There were no speakers in opposition to this designation. The Commission also has received a letter in support of the designation from a local resident. Summary This elegant commercial building, constructed in 1904-05 for the Gorham Manufacturing Company, contained its wholesale and retail showrooms, offices, and workshops. Designed by Stanford White of the prominent architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White, the eight-story building is an adaptation of an early Florentine Renaissance sty le palazzo incorporating a two-story arcade, a four-story mid-section, and a two-story loggia. -

The Gilding Arts Newsletter

The Gilding Arts Newsletter ...an educational resource for Gold Leaf Gilding CHARLES DOUGLAS GILDING STUDIO Seattle, WA February 8, 2020 Quick Links Gilding Arts Newsletter Quiz! Quick Links And the Winner from the Workshop Registration Form (for January Klimt Question is... mail-in registration only) Congratulations to Gilding Arts Newsletter member A Gilder's Journal Tatyana from Texas for submitting the first correct (Blog) answer to last issue's Klimt Quiz! Tatyana's beautiful Georgian Bay Art artwork and photography can be seen here on Conservation Instagram. The quiz question asked what materials were used to Gilding Studio...on Twitter create some of the raised swirling design Uffizi Gallery elements on Klimt's mural Beethoven Frieze Galleria and what other metal dell'Accademia di Firenze was used in the makeup Portrait of of the gold leaf? Adele Bloch-Bauer I Frye Art Museum Seattle Art Museum As outlined in a paper by Alexandra Matzner for the International Institute for Conservation of Historic Society of Gilders and Artistic Works and based upon conservation treatment of this particular work by Klimt, his areas Metropolitan Museum of Relief were comprised of Chalk and animal glue, of Art the same material we often refer to as Pastiglia, or The Fricke Collection Raised Gesso (Chalk being a form of Calcium Carbonate). The gold leaf was shown to consist of 5% Palace of Versailles copper with the remainder gold. Museo Thyssen- During my recent visit in January to the Neue Galerie Bornemisza during the Winter Quarter Gilding Week I once again studied Gustav Sepp Leaf Products Klimt's Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, which also exhibits raised gilded design Gilded Planet elements that are likely the same or a similar approach to Join our list the pastiglia technique where gesso is slowly dripped or drawn in a heavy deposit to create a raised effect. -

Metals and Metal Products Tariff Schedules of the United States

251 SCHEDULE 6. - METALS AND METAL PRODUCTS TARIFF SCHEDULES OF THE UNITED STATES SCHEDULE 6. - METALS AND METAL PRODUCTS 252 Part 1 - Metal-Bearing Ores and Other Metal-Bearing Schedule 6 headnotes: Materials 1, This schedule does not cover — Part 2 Metals, Their Alloys, and Their Basic Shapes and Forms (II chemical elements (except thorium and uranium) and isotopes which are usefully radioactive (see A. Precious Metals part I3B of schedule 4); B. Iron or Steel (II) the alkali metals. I.e., cesium, lithium, potas C. Copper sium, rubidium, and sodium (see part 2A of sched D. Aluminum ule 4); or E. Nickel (lii) certain articles and parts thereof, of metal, F. Tin provided for in schedule 7 and elsewhere. G. Lead 2. For the purposes of the tariff schedules, unless the H. Zinc context requires otherwise — J. Beryllium, Columbium, Germanium, Hafnium, (a) the term "precious metal" embraces gold, silver, Indium, Magnesium, Molybdenum, Rhenium, platinum and other metals of the platinum group (iridium, Tantalum, Titanium, Tungsten, Uranium, osmium, palladium, rhodium, and ruthenium), and precious- and Zirconium metaI a Iloys; K, Other Base Metals (b) the term "base metal" embraces aluminum, antimony, arsenic, barium, beryllium, bismuth, boron, cadmium, calcium, chromium, cobalt, columbium, copper, gallium, germanium, Part 3 Metal Products hafnium, indium, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, A. Metallic Containers molybdenum, nickel, rhenium, the rare-earth metals (Including B. Wire Cordage; Wire Screen, Netting and scandium and yttrium), selenium, silicon, strontium, tantalum, Fencing; Bale Ties tellurium, thallium, thorium, tin, titanium, tungsten, urani C. Metal Leaf and FoU; Metallics um, vanadium, zinc, and zirconium, and base-metal alloys; D, Nails, Screws, Bolts, and Other Fasteners; (c) the term "meta I" embraces precious metals, base Locks, Builders' Hardware; Furniture, metals, and their alloys; and Luggage, and Saddlery Hardware (d) in determining which of two or more equally specific provisions for articles "of iron or steel", "of copper", E. -

Louis Comfort Tiffany: a Bibliography, Relevant to the Man, His Work, and His Oyster Bay, Long Island, Home.”

Please cite as: Spinzia, Judith Ader, “Louis Comfort Tiffany: A Bibliography, Relevant to the Man, His Work, and His Oyster Bay, Long Island, Home.” www.spinzialongislandestates.com Louis Comfort Tiffany: A Bibliography Relevant to the Man, His Work, and His Oyster Bay, Long Island, Home compiled by Judith Ader Spinzia . The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum, Winter Park, FL, has photographs of Laurelton Hall. Harvard Law School, Manuscripts Division, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, has Charles Culp Burlingham papers. Sterling Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT, has papers and correspondence filed under the Mitchell–- Tiffany papers. Savage, M. Frederick. Laurelton Hall Inventory, 1919. Entire inventory can be found in the Long Island Studies Institute, Hofstra University, Hempstead, LI. The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA, has Edith Banfield Jackson papers. Tiffany & Company archives are in Parsippany, NJ. “American Country House of Louis Comfort Tiffany.” International Studio 33 (February 1908):294-96. “Artists Heaven; Long Island Estate of Louis Tiffany To Be an Artists' Home.” Review 1 (November 1, 1919):533. Baal-Teshuva, Jacob. Louis Comfort Tiffany. New York: Taschen Publishing Co., 2001. Bedford, Stephen and Richard Guy Wilson. The Long Island Country House, 1870-1930. Southampton, NY: The Parrish Art Museum, 1988. Bing, Siegfried. Artistic America, Tiffany Glass, and Art Nouveau. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, [1895-1903] 1970. [reprint, edited by Robert Koch] Bingham, Alfred Mitchell. The Tiffany Fortune and Other Chronicles of a Connecticut Family. Chestnut Hill, MA: Abeel and Leet Publishers, 1996. Brownell, William C. “The Younger Painters of America.” Scribner's Monthly July 1881:321-24. Burke, Doreen Bolger. -

Bronx Community College University Heights Campus

Bronx Community College University Heights Campus The University Heights Campus of Bronx Community College, a 19th century gem, is the first community college campus to be named a national historic landmark. Announcing the designation on Oct. 17, 2012, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar called the original buildings “a nationally significant example of Beaux-Arts architecture in the United States, and among the most important works by Stanford White, partner in McKim, Mead & White, the preeminent American architectural firm at the turn of the 20th century.” The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission first designated the buildings a landmark in 1966. The City University of New York bought the University Heights Campus from New York University in 1973 as a new home for Bronx Community College. In 1979, the buildings joined the National Register of Historic Places. In 2012, CUNY completed Stanford White’s quadrangle – first conceived in 1892 – with the architecturally harmonious and technologically advanced North Hall and Library, designed by Robert A.M. Stern. What follows comes from the college’s National Historic Landmark application. It was written by Easton Architects, a consultant to Bronx Community College on historic preservation. The University Heights Campus is a tour-de-force of Beaux-Arts influenced American Renaissance architecture. Stanford White of the renowned firm of McKim, Mead & White designed the campus for New York University in a bucolic setting on a bluff in the Bronx overlooking the Harlem River. NYU’s desire for a more spacious and architecturally unified campus followed important design trends for academic institutions of higher learning at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. -

BOWERY BANK of NEW YORK BUILDING, 124 Bowery (Aka 124-126 Bowery, 230 Grand Street), Manhattan Built: 1900-02; Architect(S): York & Sawyer

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 26, 2012, Designation List 457 LP-2518 BOWERY BANK OF NEW YORK BUILDING, 124 Bowery (aka 124-126 Bowery, 230 Grand Street), Manhattan Built: 1900-02; architect(s): York & Sawyer Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 470, Lot 64 On May 15, 2012, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Bowery Bank of New York Building and the proposed designation of the Landmark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Four people testified in favor of designation, including representatives of City Councilmember Margaret Chin, the Bowery Alliance of Neighbors, the Historic Districts Council, and the Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in American. The Commission has also received a letter from the owner in opposition to designation. Summary Completed in 1902, the Bowery Bank of New York is the earliest surviving building by the architectural firm of York & Sawyer in New York City. Located at the northwest corner of the Bowery and Grand Street, it is flanked on both sides by the former Bowery Savings Bank, a designated Landmark that was constructed during the years when both York and Sawyer were employed by the building’s architect, McKim Mead & White. While the neighboring facades are distinguished by massive pediments and Corinthian columns that suggest an ancient Roman temple, the straightforward monumentality of the Bowery Bank expressed its function as a modern place of work. The New York Daily Tribune praised the building when it opened, saying it “ranks with the best of our modern New York banks.” Edward P. -

Former Thomas B. Clarke Residence

Landmarks Preservation Commission Se~tember 11, 1979, Designation List 127 LP-1047 COLLECIORS CLUB BUTIDJNG {Forner Thomas B. Clarke Residence), 22 East 35th Street. Borough of Manhattan. Built 1901-02; architects McKim, Mead & White. Landnark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 864, Lot 53. On May 8, 1979, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Collectors Club Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 10). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Six witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS This channing building, now the horre of the Collectors Club, was constructed in 1901-02 as the residence of Thomas Benedict Clarke in the fashionable Murray Hill section of New York. An especially notable example of nee-Georgian architecture, it was designed by the finn of McKim, Mead & White, and is one of their outstanding residential designs in New York City. Murray Hill had begilll to be developed with residences in the mid-19th century. The area took its narce from the conntry estate of Robert and Mary Murray .1 According to legend, during the Revolutionary War, Mary Murray had detained General Howe at the family house on their conntry estate, thus allowing George Washington to escape further northward ~2 Following the opening of Lexington and Fourth Avenues through the area in 1848, rows of brownstone residences were quickly built ·along the side streets. Socially prominent and wealthy residents, such as A.T. -

Town/Village of Harrison Comprehensive Plan 2006 DRAFT

Town/Village of Harrison Comprehensive Plan 2006 M A IN S T COLUMBUS AV PARK AV DUXBURY RD C EN TU R Y R I D G E R D DRAFT AD H A E V IN E M A H A R R I S O N A V P U R D Y H ST A V I L A N DS C Y T R OAKLAND AV D January 2007 G TAYLO Table of Contents Chapter 1: Comprehensive Plan Summary Chapter 2: Town-wide Analyses Chapter 3: Neighborhood Analyses Chapter 4: Plan Concepts and Future Land Use Plan Table of Contents Chapter 1: Comprehensive Plan Summary Chapter 2: Town-wide Analyses 2.1 Changes since the 1988 Update 2-1 2.2 Previous Plans 2-3 2.3 The Planning Process 2-3 2.4 Development History 2-3 2.5 Context: The Region and Town 2-4 2.5.1 The Region – A Region at Risk 2-6 2.5.2 Westchester County Planning Strategies – Patterns for Westchester 2-6 2.6 Demographics 2-8 2.6.1 Population 2-8 2.6.2 Housing stock 2-9 2.7 Planning Concerns: Development Controls 2-12 2.7.1 Land Use 2-12 2.7.2 Town Development Trends 2-14 2.7.3 Neighborhoods 2-17 2.7.4 Zoning 2-19 2.7.5 Development Controls 2-22 2.8 Transportation and Parking 2-25 2.8.1 Hierarchy of Roadways 2-25 2.8.2 Other Transportation 2-28 2.8.3 Planning Concerns: Circulation and Parking Controls 2-32 2.9 Community Facilities, Services, and Infrastructure 2-34 2.9.1 Emergency Services 2-34 2.9.2 Education 2-36 2.9.3 Water, Sewer and Stormwater Management 2-38 2.10 Natural Environment 2-41 2.11 Open Space and Recreation 2-45 2.11.1 Open Space and Recreation Plan 2-46 2.11.2 Private Recreation 2-48 Chapter 3: Neighborhood Analyses 3.1 Harrison Central Business District 3-1 3.2 Downtown -

Design Guide & Recommendations

Irvington Historic District Design Guide & Recommendations Village of Irvington, New York June 5, 2017 INTENDED USE OF THE IRVINGTON HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGN GUIDE AND RECOMMENDATIONS VILLAGE OF IRVINGTON, NY On June 19, 2017, the Board of Trustees of the Village of Irvington adopted the Historic District Design Guide and Recommendations. In doing so, the Board of Trustees passed a Resolution 2017-094 memorializing its intent on how the guide should be applied. Below is a copy of that resolution. RESOLUTION 2017-094 ADOPTION OF HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGN GUIDE AND RECOMMENDATIONS WHEREAS, the 2003 Comprehensive Plan recommended WHEREAS, in January 2014, the Irvington Historic the designation of the Main Street area as a historic district and the District was officially listed on the National Register of Historic adoption of a historic district ordinance; and Places; and WHEREAS, in February 2010, the Board of Trustees, in WHEREAS, the designation on the National Register recognition of the distinctive and important historical and applies to the Main Street area as a whole, rather than to any architectural identity of the Main Street Area, amended the Board individual house in the Irvington Historic District; and of Architectural Review chapter of the Village Code to list as one of its purposes, “Protect the historic character of the Village, WHEREAS, the Historic District Committee, in including, in particular, the Main Street Historic Area,” but did not consultation with Stephen Tilley Associates, developed the provide specific guidance -

KINGSCOTE Other Name/Site Number: George Noble Jones House David King Jr

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 KINGSCOTE Page 1 NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: KINGSCOTE Other Name/Site Number: George Noble Jones House David King Jr. House 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Bellevue Avenue Not for publication: City/Town: Newport Vicinity: State: RI County: Newport Code: 005 Zip Code: 02840 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s):JL Public-Local:__ District:__ Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 I__ buildings ___ sites ___ structures I__ objects 1 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 KINGSCOTE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

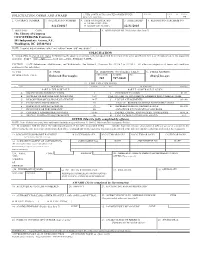

FEDLINK Preservation Basic Services Ordering

SOLICITATION, OFFER AND AWARD 1. THIS CONTRACT IS A RATED ORDER UNDER RATING PAGE OF PAGES DPAS (15 CFR 700) 1 115 2. CONTRACT NUMBER 3. SOLICITATION NUMBER 4. TYPE OF SOLICITATION 5. DATE ISSUED 6. REQUISITION/PURCHASE NO. G SEALED BID (IFB) S-LC04017 G NEGOTIATED (RFP) 12/31/2003 7. ISSUED BY CODE 8. ADDRESS OFFER TO (If other than Item 7) The Library of Congress OCGM/FEDLINK Contracts 101 Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC 20540-9414 NOTE: In sealed bid solicitations “offer” and “offeror” mean “bid” and “bidder” SOLICITATION 9. Sealed offers in original and copies for furnishing the supplies or services in the Schedu.le will be received at the place specified in Item 8, or if handcarried, in the depository located in Item 7 until __2pm______ local time __Tues., February 4, 2004_. CAUTION -- LATE Submissions, Modifications, and Withdrawals: See Section L, Provision No. 52.214-7 or 52.215-1. All offers are subject to all terms and conditions contained in this solicitation. 10. FOR A. NAME B. TELEPHONE (NO COLLECT CALLS) C. E-MAIL ADDRESS INFORMATION CALL: Deborah Burroughs AREA CODE NUMBER EXT. [email protected] 202 707-0460 11. TABLE OF CONTENTS ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) PART I - THE SCHEDULE PART II - CONTRACT CLAUSES A SOLICITATION/CONTRACT FORM 1 I CONTRACT CLAUSES 91-97 B SUPPLIES OR SERVICES AND PRICE/COST 3-23 PART III - LIST OF DOCUMENTS, EXHIBITS AND OTHER ATTACH. C DESCRIPTION/SPECS./WORK STATEMENT 24-77 J LIST OF ATTACHMENTS 98-100 D PACKAGING AND MARKING 78 PART IV - REPRESENTATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS E INSPECTION AND ACCEPTANCE 79 K REPRESENTATIONS, CERTIFICATIONS 101-108 F DELIVERIES OR PERFORMANCE 80 AND OTHER STATEMENTS OF OFFERORS G CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION DATA 81-89 L INSTRS., CONDS., AND NOTICES TO OFFERORS 109-114 H SPECIAL CONTRACT REQUIREMENTS 90 M EVALUATION FACTORS FOR AWARD 115 OFFER (Must be fully completed by offeror) NOTE: Item 12 does not apply if the solicitation includes the provisions at 52.214-16, Minimum Bid Acceptance Period.