Gilding Through the Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materials & Process

Sculpture: Materials & Process Teaching Resource Developed by Molly Kysar 2001 Flora Street Dallas, TX 75201 Tel 214.242.5100 Fax 214.242.5155 NasherSculptureCenter.org INDEX INTRODUCTION 3 WORKS OF ART 4 BRONZE Material & Process 5-8 Auguste Rodin, Eve, 1881 9-10 George Segal, Rush Hour, 1983 11-13 PLASTER Material & Process 14-16 Henri Matisse, Madeleine I, 1901 17-18 Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman (Fernande), 1909 19-20 STEEL Material & Process 21-22 Antony Gormley, Quantum Cloud XX (tornado), 2000 23-24 Mark di Suvero, Eviva Amore, 2001 24-25 GLOSSARY 26 RESOURCES 27 ALL IMAGES OF WORKS OF ART ARE PROTECTED UNDER COPYRIGHT. ANY USES OTHER THAN FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ARE STRICTLY FORBIDDEN. 2 Introduction This resource is designed to introduce students in 4th-12th grades to the materials and processes used in modern and traditional sculpture, specifically bronze, plaster, and steel. The featured sculptures, drawn from the collection of the Nasher Sculpture Center, range from 1881 to 2001 and represent only some of the many materials and processes used by artists whose works of art are in the collection. Images from this packet are also available in a PowerPoint presentation for use in the classroom, available at nashersculpturecenter.org. DISCUSS WITH YOUR STUDENTS Artists can use almost any material to create a work of art. When an artist is deciding which material to use, he or she may consider how that particular material will help express his or her ideas. Where have students seen bronze before? Olympic medals, statues… Plaster? Casts for broken bones, texture or decoration on walls.. -

Structural Treatment of a Monumental Japanese Bronze Eagle from the Meiji Period Author(S): Marianne Russell-Marti and Robert F

Article: Structural treatment of a monumental Japanese bronze eagle from the Meiji period Author(s): Marianne Russell-Marti and Robert F. Marti Source: Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Three, 1995 Pages: 39-63 Compilers: Julie Lauffenburger and Virginia Greene th © 1996 by The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works, 1156 15 Street NW, Suite 320, Washington, DC 20005. (202) 452-9545 www.conservation-us.org Under a licensing agreement, individual authors retain copyright to their work and extend publications rights to the American Institute for Conservation. Objects Specialty Group Postprints is published annually by the Objects Specialty Group (OSG) of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works (AIC). A membership benefit of the Objects Specialty Group, Objects Specialty Group Postprints is mainly comprised of papers presented at OSG sessions at AIC Annual Meetings and is intended to inform and educate conservation-related disciplines. Papers presented in Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Three, 1995 have been edited for clarity and content but have not undergone a formal process of peer review. This publication is primarily intended for the members of the Objects Specialty Group of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works. Responsibility for the methods and materials described herein rests solely with the authors, whose articles should not be considered official statements of the OSG or the AIC. The OSG is an approved division of the AIC but does not necessarily represent the AIC policy or opinions. STRUCTURAL TREATMENT OF A MONUMENTAL JAPANESE BRONZE EAGLE FROM THE MEIJI PERIOD Marianne Russell-Marti and Robert F. -

The Bonefolder: an E-Journal for the Bookbinder and Book Artist Surface Gilding by James Reid-Cunningham

Bexx Caswell’s binding of Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman; Illustrations by Jim Spanfeller. Hallmark, 1969. From the 2009 Bind-O-Rama. Volume 6, Number 1, Fall 2009 The Bonefolder: an e-journal for the bookbinder and book artist Surface Gilding By James Reid-Cunningham 28 Figure 1. The House South of North. Calfskin, gold leaf, Figure 2. Transfer leaf. palladium leaf, kidskin, fish skin, goatskin, box calf, abalone. Gilding on large flat surfaces is best done with transfer leaf Bound 2006. (also called patent leaf), which is gold leaf mounted on a piece Traditional binding decoration utilizes gold leaf to create of thin tissue that allows easily handling without wrinkling or discrete highlights, as in gold finishing. What I refer to as breaking the gold leaf. Transfer leaf can be cut with a scissors. “surface gilding” covers a binding with gold leaf over large Use a scissors reserved only for this task because any scratch areas, even over entire boards. This kind of decoration is rare or little bit of adhesive on the blade will pull the leaf and in bookbinding history, but can be seen in Art Deco bindings break it. When using loose gold leaf, it is necessary to adhere done in France during the 1920s and 1930s. Surface gilding the leaf to the substrate using oil or Vaseline. has become increasingly common among design binders in It sometimes seems that any adhesive ever invented recent years. Whether bound in leather, paper or vellum, has been used at one point or another to adhere gold to a surface gilding gives a spectacularly luxurious effect to a book, so there are many choices of what to use. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Casting Rodin’s Thinker Sand mould casting, the case of the Laren Thinker and conservation treatment innovation Beentjes, T.P.C. Publication date 2019 Document Version Other version License Other Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Beentjes, T. P. C. (2019). Casting Rodin’s Thinker: Sand mould casting, the case of the Laren Thinker and conservation treatment innovation. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Introduction In the night of the 16th to 17th January 2007, a bronze statue by Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), the Thinker, disappeared from the sculpture garden of the Singer Museum in Laren, the Netherlands. Only days after the theft, the bronze was retrieved, albeit heavily damaged. -

Or on the ETHICS of GILDING CONSERVATION by Elisabeth Cornu, Assoc

SHOULD CONSERVATORS REGILD THE LILY? or ON THE ETHICS OF GILDING CONSERVATION by Elisabeth Cornu, Assoc. Conservator, Objects Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Gilt objects, and the process of gilding, have a tremendous appeal in the art community--perhaps not least because gold is a very impressive and shiny currency, and perhaps also because the technique of gilding has largely remained unchanged since Egyptian times. Gilding restorers therefore have enjoyed special respect in the art community because they manage to bring back the shine to old objects and because they continue a very old and valuable craft. As a result there has been a strong temptation among gilding restorers/conservators to preserve the process of gilding rather than the gilt objects them- selves. This is done by regilding, partially or fully, deteriorated gilt surfaces rather than attempting to preserve as much of the original surface as possible. Such practice may be appropriate in some cases, but it always presupposes a great amount of historic knowledge of the gilding technique used with each object, including such details as the thickness of gesso layers, the strength of the gesso, the type of bole, the tint and karatage of gold leaf, and the type of distressing or glaze used. To illustrate this point, I am asking you to exercise some of the imagination for which museum conservators are so famous for, and to visualize some historic objects which I will list and discuss. This will save me much time in showing slides or photographs. Gilt wooden objects in museums can be broken down into several subcategories: 1) Polychromed and gilt sculptures, altars Examples: baroque church altars, often with polychromed sculptures, some of which are entirely gilt. -

Selective Laser Sintering Used to Create Bronze Sculpture for Basilica at Notre Dame University

Selective Laser Sintering Used to Create Bronze Sculpture for Basilica at Notre Dame University The additive fabrication process known as Selective Laser Sintering (SLS®) is best known for producing tough, durable parts for rigorous testing and wax patterns for investment casting direct from 3D Computer Aided Design (CAD) data. SLS® has long been a favorite of many designers and engineers and has now found a new proponent in contemporary artist Robert Graham. Historically, Graham has used traditional methods for producing his cast artwork but those methods are known for being slow, laborious and usually result in a loss of some artistic detail. Graham, being the progressive artist that he is, was already using other additive fabrication methods for previous projects and was introduced to the benefits of SLS® technology during his extensive relationship with American Precision Prototyping (APP). Graham was commissioned by the University of Notre Dame to create a 6 foot, full body bronze statue of Father Basile Antoine-Marie Moreau, c.s.c for the Basilica of the Sacred Heart Church at the University. Graham, equipped with the knowledge of a new and improved technology, was faced with the challenge of pursuing this project with traditional methods or with this new additive fabrication process that would not only shorten the project time but would also yield a truer representation of his original sculpture. Finished Bronze Mr. Robert Graham, world renowned Venice, CA artist and sculptor has been creating magnificent works of art since the mid 1960’s. His works have been featured in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, Museum of Modern Art in Paris, France, Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and many other galleries and museums around the world. -

Decorative Arts and Sculpture—Outdoor Sculpture Coatings

Decorative Arts and Sculpture | Featured Project | Outdoor Sculpture Coatings Research Since the J. Paul Getty Museum acquired an outdoor sculpture collection from the Fran and Ray Stark Revocable Trust in 2006, the care of the collection became the responsibility of the Museum's Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department. The department entered a new field of study, initiating research into the materials, techniques and conservation of outdoor sculpture and we had the opportunity to engage with the living artists. Of the 28 works, most are made from cast bronze and lead, but there are also fabrications out of stainless steel, painted metal, and ceramic. One area of research involves the performance evaluation of protective coatings including cold wax and clear lacquers. Wax is one of the most common materials used in the maintenance of outdoor bronze sculpture and has been incorporated into our yearly maintenance plan over the years. Proprietary paste waxes were initially applied cold over pre- existing Incralac—a commercial acrylic clear lacquer. Since it was commonly used by conservators in the United States, Butcher’s paste wax was adopted. However, either it was a bad batch or the formula changed: we noted a decrease in Conservators work on Horse (Gift of Fran and Ray Stark. © performance. One of the challenges in using a proprietary Estate of Elisabeth Frink. 2005.106.1) product is their trade secret becomes our blindness to changes that may impact our application. A preferred lab-made wax blend was developed—based on recipes from the National Park Service—by modifying the melting point, substituting solvents, and changing the blended components to suit a hot California climate. -

Perspectives on Sculpture Conservation Modelling Copper and Bronze Corrosion

Perspectives on Sculpture Conservation Modelling Copper and Bronze Corrosion Helena Strandberg Akademisk avhandling för avläggande av filosofie doktorsexamen i Miljövetenskap med inriktning mot Kemi. Med tillstånd av Sektionen för Miljövetenskap, Göteborgs Universitet och Chalmers Tekniska Högskola, försvaras avhandlingen offentligt fredagen den 19 september 1997 kl. 1015 i sal KS 101, Kemihuset, Chalmers. Fakultetsopponent är Dr. Jan Henrikssen, NILU, Norge. Avdelningen för Oorganisk Kemi Göteborgs Universitet 1997 ISBN 91-7197-539-X Published in Göteborg, Sweden, August 1997 Printed at Chalmers Reproservice, Göteborg 1997 118 pages + 2 appendices + 8 appended papers Cover pieture: Dancing girIs ("Danserskor") by Carl Milles in front of the Museum of Art in Göteborg. The seulpture was east in 1915 and plaeed outdoors 1952. Photo: Helena Strandberg, 1997. Perspectives on Bronze Sculpture Conservation Modelling Copper and Bronze Corrosion DoctoraI dissertation for the Ph. D. degree Helena Strandberg Department ofInorganic Chemistry, Göteborg University, 412 96, Göteborg, Sweden Abstract This dissertation pres~nts different perspectives on the conservation of bronze sculptures and copper objects in outdoor environments. The problem complex is described regarding values assigned to sculptures, the condition of objects, deterioration processes in outdoor environments, and principles for conservation interventions in a historical and a modem perspective. The emphasis, however, is laid on laboratory investigations of crucial factors in deterioration processes. The role of trace amounts of S02, 03, N02 and NaCI on the atmospheric corrosion of copper, bronze and patina compounds was investigated using on-line gas analysis, gravimetry , and different corrosion product characterization techniques. Laboratory studies showed good agreement with studies from the field. It was found that a black cuprite patina (CU20) formed on copper in humid atmospheres at very low concentrations of S02, while higher levels of S02 passivated the surface. -

Gilding with Kolner Burnishing Clay and Insta-Clay by Lauren Sepp

Gilding with Kolner Burnishing Clay and Insta-Clay By Lauren Sepp ’ve been asked many times by custom framing re- achieve different shades. The white Burnishing Clay tailers if there is an easier way to water gild and can be tinted with Mixol tinting agents up to 5 percent I burnish a surface, as it’s generally agreed upon that by weight to achieve any color you desire. traditional water gilding is a labor-intensive method. Both the Burnishing Clay and Insta-Clay can be Kolner products address that demand by streamlining applied to many different surfaces. Certain nonpo- the water gilding process, which would otherwise in- rous substrates require no sealing before application clude many more steps. of the clay: Plexiglas and other plastics, sealed woods, Kolner Products, based in Germany, formulated a nonporous paints, and lacquered metals. Unsealed water-based, single-layer, burnishable gilders’ clay for metals may require a primer. Smooth plastics and water gilding in 1985 called Kolner Burnishing Clay. metals may require a light sanding to promote good This product combines and replaces the glue size, ges- adhesion. Porous surfaces such as matboard, paper, so, and bole layers with a single product. The clay is parchment, raw wood, textiles, unglazed ceramics, premixed with an acrylic binder and only needs to be stone, plaster, traditional gesso and compo orna- thinned slightly and stirred. There is no heating, dis- ments require a sealer before applying the clays. In solving of glues, or straining. There is also a sprayable many applications, shellac is a good all-around sealer. -

Lost Wax: an Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Kevin Bell SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2009 Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Kevin Bell SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Art Practice Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Kevin, "Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal" (2009). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 735. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/735 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Bell, Kevin Academic Director: Diallo, Souleye Project Advisor: Diop, Issa University of Denver International Studies Africa, Senegal, Dakar Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Senegal Arts and Culture, SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2009 Table of Contents ABSTRACT: ................................................................................................................................................................1 I. LEARNING GOALS: .........................................................................................................................................2 I. RESOURCES AND METHODS: ......................................................................................................................3 -

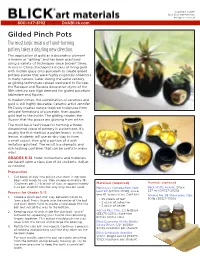

Gilded Pinch Pots the Most Basic Means of Hand-Forming Pottery Takes a Dazzling New Direction

Copyright © 2018 Dick Blick Art Materials All rights reserved 800-447-8192 DickBlick.com Gilded Pinch Pots The most basic means of hand-forming pottery takes a dazzling new direction. The application of gold as a decorative element is known as "gilding" and has been practiced using a variety of techniques since ancient times. Artists in China developed a means of firing gold with molten glass onto porcelain to create gilded pottery pieces that were highly prized by collectors in many nations. Later during the same century, as gilding techniques spread westward to Europe, the Baroque and Rococo decorative styles of the 18th century saw high demand for gilded porcelain tableware and figures. In modern times, the combination of ceramics and gold is still highly desirable. Ceramic artist Jennifer McCurdy creates nature-inspired sculptures from delicate formations of porcelain, then applies gold leaf to the inside. The gilding creates the illusion that the pieces are glowing from within. The most basic technique for forming a three- dimensional piece of pottery is a pinch pot. It's usually the first method a potter learns. In this lesson, students will use air-dry clay to form a small vessel, then gild a portion of it with imitation gold leaf. The result is a dramatic and rich-looking container that can be useful in many ways. GRADES K-12 Note: Instructions and materials are based upon a class size of 24 students. Adjust as needed. Preparation 1. Cut block of clay into pieces and store in zip-lock bags until ready to use. -

The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD FORM OF MANUSCRIPT Eleanor Hughes, Executive Editor All manuscripts must be typed and double-spaced (including quotations and Charles Dibble, Associate Editor endnotes). Contributors are encouraged to send manuscripts electronically; Amanda Kodeck please check with the editor/manager of curatorial publications as to compat- Amy Landau ibility of systems and fonts if you are using non-Western characters. Include on Julie Lauffenburger a separate sheet your name, home and business addresses, telephone, and email. All manuscripts should include a brief abstract (not to exceed 100 words). Manuscripts should also include a list of captions for all illustrations and a separate list of photo credits. VOLUME EDITOR Amy Landau FORM OF CITATION Monographs: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; italicized or DESIGNER underscored title of monograph; title of series (if needed, not italicized); volume Jennifer Corr Paulson numbers in arabic numerals (omitting “vol.”); place and date of publication enclosed in parentheses, followed by comma; page numbers (inclusive, not f. or ff.), without p. or pp. © 2018 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, L. H. Corcoran, Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I–IV Centuries), Maryland 21201 Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 56 (Chicago, 1995), 97–99. Periodicals: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; title in All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written double quotation marks, followed by comma, full title of periodical italicized permission of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland.