Japanese Lacquer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Price Collection JAKUCHU and the Age of Imagination the Etsuko

The Price Collection JAKUCHU and The Age of Imagination The Etsuko and Joe Price Collection based in California is world-renowned for its superb Edo period paintings. The Exhibition entitled The Price Collection-Jakuchû and the Age of Imagination will be held at the Tokyo National Museum (Ueno Park, Tokyo) from July 4th through August 27th, 2006. Some fifty years ago, Joe Price became fascinated by, and began to collect, paintings by the individualist artists of the Edo period, a field ignored by the art historians of the time. Mr. Price dubbed his collection and his foundation the Shin’enkan, borrowing one of the studio names of Itô Jakuchû (1716-1800), an individualist painter whose popularity has grown in recent years. Today the Price Collection centers around a superb group of works by Jakuchû, along with major works by Jakuchû ’s other Kansai region contemporaries such as Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799) and Mori Sosen (1747-1821), along with Edo-based Rimpa artists Sakai Hôitsu (1761-1828) and Suzuki Kiitsu (1796-1858). The marvels of the collection include paintings by ukiyo-e artists and other painters who have recently attracted great attention from art lovers. This exhibition presents a selection of 101 works chosen jointly by Mr. Price and the Tokyo National Museum staff from more than 600 works in the collection. The exhibition is divided into five sections, with the paintings arranged according to their artistic lineage. A special feature of this exhibition is its avoidance of glass cases in one of the galleries and use of careful lighting effects to create a display environment similar to an Edo period viewing experience. -

The Gilding Arts Newsletter

The Gilding Arts Newsletter ...an educational resource for Gold Leaf Gilding CHARLES DOUGLAS GILDING STUDIO Seattle, WA February 8, 2020 Quick Links Gilding Arts Newsletter Quiz! Quick Links And the Winner from the Workshop Registration Form (for January Klimt Question is... mail-in registration only) Congratulations to Gilding Arts Newsletter member A Gilder's Journal Tatyana from Texas for submitting the first correct (Blog) answer to last issue's Klimt Quiz! Tatyana's beautiful Georgian Bay Art artwork and photography can be seen here on Conservation Instagram. The quiz question asked what materials were used to Gilding Studio...on Twitter create some of the raised swirling design Uffizi Gallery elements on Klimt's mural Beethoven Frieze Galleria and what other metal dell'Accademia di Firenze was used in the makeup Portrait of of the gold leaf? Adele Bloch-Bauer I Frye Art Museum Seattle Art Museum As outlined in a paper by Alexandra Matzner for the International Institute for Conservation of Historic Society of Gilders and Artistic Works and based upon conservation treatment of this particular work by Klimt, his areas Metropolitan Museum of Relief were comprised of Chalk and animal glue, of Art the same material we often refer to as Pastiglia, or The Fricke Collection Raised Gesso (Chalk being a form of Calcium Carbonate). The gold leaf was shown to consist of 5% Palace of Versailles copper with the remainder gold. Museo Thyssen- During my recent visit in January to the Neue Galerie Bornemisza during the Winter Quarter Gilding Week I once again studied Gustav Sepp Leaf Products Klimt's Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, which also exhibits raised gilded design Gilded Planet elements that are likely the same or a similar approach to Join our list the pastiglia technique where gesso is slowly dripped or drawn in a heavy deposit to create a raised effect. -

Metals and Metal Products Tariff Schedules of the United States

251 SCHEDULE 6. - METALS AND METAL PRODUCTS TARIFF SCHEDULES OF THE UNITED STATES SCHEDULE 6. - METALS AND METAL PRODUCTS 252 Part 1 - Metal-Bearing Ores and Other Metal-Bearing Schedule 6 headnotes: Materials 1, This schedule does not cover — Part 2 Metals, Their Alloys, and Their Basic Shapes and Forms (II chemical elements (except thorium and uranium) and isotopes which are usefully radioactive (see A. Precious Metals part I3B of schedule 4); B. Iron or Steel (II) the alkali metals. I.e., cesium, lithium, potas C. Copper sium, rubidium, and sodium (see part 2A of sched D. Aluminum ule 4); or E. Nickel (lii) certain articles and parts thereof, of metal, F. Tin provided for in schedule 7 and elsewhere. G. Lead 2. For the purposes of the tariff schedules, unless the H. Zinc context requires otherwise — J. Beryllium, Columbium, Germanium, Hafnium, (a) the term "precious metal" embraces gold, silver, Indium, Magnesium, Molybdenum, Rhenium, platinum and other metals of the platinum group (iridium, Tantalum, Titanium, Tungsten, Uranium, osmium, palladium, rhodium, and ruthenium), and precious- and Zirconium metaI a Iloys; K, Other Base Metals (b) the term "base metal" embraces aluminum, antimony, arsenic, barium, beryllium, bismuth, boron, cadmium, calcium, chromium, cobalt, columbium, copper, gallium, germanium, Part 3 Metal Products hafnium, indium, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, A. Metallic Containers molybdenum, nickel, rhenium, the rare-earth metals (Including B. Wire Cordage; Wire Screen, Netting and scandium and yttrium), selenium, silicon, strontium, tantalum, Fencing; Bale Ties tellurium, thallium, thorium, tin, titanium, tungsten, urani C. Metal Leaf and FoU; Metallics um, vanadium, zinc, and zirconium, and base-metal alloys; D, Nails, Screws, Bolts, and Other Fasteners; (c) the term "meta I" embraces precious metals, base Locks, Builders' Hardware; Furniture, metals, and their alloys; and Luggage, and Saddlery Hardware (d) in determining which of two or more equally specific provisions for articles "of iron or steel", "of copper", E. -

Download the Paper

Permanent Secretariat Av. Drassanes, 6-8, planta 21 08001 Barcelona Tel. + 34 93 256 25 09 Fax. + 34 93 412 34 92 Strand 2: The Historiography of Art Nouveau (looking back on the past) Paris and Kyoto—Asai Chu making a bridge onto the Art Nouveau from Japan Mori Hitoshi (Professor, Kanazawa College of Art) In Japan, from the fifteenth century onwards, the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and the incense ceremony have existed as arts and the art theories cultivated there gave form to basic concepts such as “mitate (likening)” or “shitsurai (arrangement)”. There, not only the actual things visible but different perspectives and entirely new concepts were presented through a variety of implements and combinations of them. On such occasions, vases, incense burners, and tea caddies were employed as “tools” to express such ideas. The significance of the existence of such works of art as tools to give form to such ideas was great. In addition, having accomplished the Meiji Restoration in the latter half of the nineteenth century, Japan became open to Western politics, economics, and culture and aimed to form a new nation-state. In doing so, thanks to Japonism, Japanese-made products were highly appreciated abroad. However, in the 1880s, Japonism diminished and export declined. As a result, the producing centers lose confidence. This trend became definite with the emergence of Art Nouveau at the Paris Exposition of 1900. On that occasion, nearly 200 people visited Paris from Japan and recognized the actual state. While, on the one hand, this answer was a scheme to secure the market by means of a price war relying on low wages, on the other hand, there were people who attempted to launch Japanese artistry out into a new art, i.e. -

Lacquerware Chemistry

Chemistry the key to our future Lacquerware Sake cup of Wajima-nuri Wajima-nuri 輪島塗Lacquerware The lacquerwares made in Wajima City, Ishikawa Japanese lacquerware is believed to have a history Prefecture are called wajima-nuri, or wajima of around 6800 years, and the oldest lacquerware lacquerware, which is prepared by repeatedly has been excavated in Ishikawa. Some of the covering wood or paper with lacquer. The lacquer reasons why lacquering has flourished around used for such craftworks is sap taken and processed Wajima area may have been that essential materials from Japanese lacquer trees. This natural resin for making lacquerware (tree that provides paint mainly consists of urushiol and may cause lacquer and wood for woodworks as well as good allergy. It also contains a catalyst called laccase, diatomite) were abundantly available, and that there and helps the lacquer to were also active markets thanks to the seaports be oxidized in the air and nearby. polymerize to make a real Here is how a lacquerware is made. Making of a hard coating. The climate wajima-nuri starts with obtaining a quality wooden in Japan, especially in basis. Any fragile parts are reinforced by putting Wajima, provides the desired fabric pieces using lacquer. As primer coating, humidity and temperature for mixture of lacquer and jinoko (powdered diatomite) Sap from urushi tree this polymerization reaction. is applied for more than twice, and raw lacquer is applied to further reinforce breakable points. Then middle and finish coatings of lacquer are applied before various decorative techniques, for example, makie (painting in colored lacquer) or chinkin (sunken gold). -

HST Catalogue

170 1 LIST – – JAPANESE INTEREST H ANSHAN TANG B OOKS LTD Unit 3, Ashburton Centre 276 Cortis Road London SW 15 3 AY UK Tel (020) 8788 4464 Fax (020) 8780 1565 Int’l (+44 20) [email protected] www.hanshan.com 4 Boehm, Christian: THE CONCEPT OF DANZO. ‘Sandalwood Images’ in Japanese Buddhist Sculpture of the 8th to 14th Centuries. London, 2012. 264 pp. 165 colour and b/w illustrations. 29x21 cm. Boards. £59.95 A detailed study examining Japanese Buddhist sculpture known as Danzo (sandalwood images) and Dangan (portable sandalwood shrines) dating from the 8th to 14th centuries. Includes Chinese examples dating from the 6th to 13th centuries which were imported into Japan and which played a major role in the establishment of the indigenous Japanese danzo tradition. 28 Little, Stephen & Lewis, Edmund J: VIEW OF THE PINNACLE. Japanese Lacquer Writing Boxes: The Lewis Collection of Suzuribako. Honolulu, 2012. xxvii, 228 pp. Colour plates (many full page) throughout. 28x21 cm. Cloth. £80.00 A beautifully-illustrated and well-written study with detailed descriptions of over 80 suzuribako (writing boxes) dating from the 14th to 20th centuries from the fine collection of Edmund and Julia Lewis. Delicious. 31 Metropolitan Museum of Art: DESIGNING NATURE. The Rinpa Aesthetic in Japanese Art. New York, 2012. 215 pp. Colour plates throughout. 27x24 cm. Wrappers. £20.00 Catalogue of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York examining the Rinpa (Rimpa) aesthetic in Japanese art, celebrated for its bold rendering of natural motifs, references to literature and poetry and experimentation with calligraphy. -

The Life of Animals in Japanese Art Jun 2–Aug 18, 2019

UPDATED: 5/30/2019 3:04:02 PM Rotation Checklist: The Life of Animals in Japanese Art Jun 2–Aug 18, 2019 Works from rotation A are on view through July 7. Works will be rotated on a rolling basis during the week of July 8-12. Some works from rotation A will go off view and not be replaced with another work. Works from rotation B are on view following July 13. The exhibition is curated by Robert T. Singer, curator and department head, Japanese art, LACMA, and Masatomo Kawai, director, Chiba City Museum of Art, in consultation with a team of esteemed of Japanese art historians. Coorganized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, the Japan Foundation, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, with special cooperation from the Tokyo National Museum. LACMA is presenting an abbreviated version of the exhibition, titled Every Living Thing: Animals in Japanese Art from September 22 through December 8, 2019. Made possible through the generous support of the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation. The Robert and Mercedes Eichholz Foundation also kindly provided a leadership gift for this exhibition. Additional funding is provided by The Exhibition Circle of the National Gallery of Art and the Annenberg Fund for the International Exchange of Art. Additional support is provided by All Nippon Airways (ANA). The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. The exhibition is part of Japan 2019, an initiative to promote Japanese culture in the United States. Press Release: https://www.nga.gov/press/exh/4874.html Order Press Images: https://www.nga.gov/press/exh/4874/images.html Press Contact: Isabella Bulkeley, (202) 842-6864 or [email protected] 1 A Cat. -

Chapter 12 a Pirate's View of the History of Art Commerce : Beyond an Oceanic View of Civilizations

Chapter 12 A Pirate's View of the History of Art Commerce : Beyond an Oceanic View of Civilizations 著者 INAGA Shigemi 会議概要(会議名, A Pirate’s View of World History : A Reversed 開催地, 会期, 主催 Perception of the Order of Things From a 者等) Global Perspective, 2016年4月27-29日, 国際日本 文化研究センター page range 107-125 year 2017-08-31 シリーズ 国際シンポジウム International Research Symposium 国際研究集会 ; 50 URL http://doi.org/10.15055/00006760 A Pirate’s View of the History of Art Commerce Chapter 12 A Pirate’s View of the History of Art Commerce: Beyond an Oceanic View of Civilizations 1 INAGA Shigemi 1. Redefining Piracy 1.1 The Battamon Disturbance Let’s begin with the battamon disturbance. In 2010, Okamoto Mitsuhiro’s “Battamon” series was exhibited at the Kobe Fashion Museum (fig.1). While the etymology of the term is uncertain, in Japan’s western Kansai region it refers to a product that is sold without going through authorized distribution routes. Batchimon, on the other hand, refers to a counterfeit or imitation item. In Japanese, batta also refers to grasshoppers (including locusts). With this in mind, Okamoto created migratory locusts clothed in leather from brand products. However, Louis Vuitton complained that this exhibit was equivalent to engaging in counterfeit sales, and it was halted. Tano Taiga engraved original bags out of wood with exactly the same pattern as those of Louis Vuitton, and it is said that a public museum had to hide their logo marks when they were put on display.2 The obstinacy of brand distributors not trying to understand jokes might invite contemptuous laughs. -

Japanese Art at the Paris and Philadelphia Expositions ≫PDF

PRESS RELEASE Seitei, Zeshin and Kyosai: Japanese Art at the Paris and Philadelphia Expositions Begins! Dates: April 24 (Sat) to May 5 (Wed), 2021 Venue: Kashima Arts (3-3-2 Kyobashi, Chuo-ku, Tokyo) Open all days / Free Admittance Kashima Arts proudly presents, Seitei, Zeshin and Kyosai: Japanese Art at the Paris and Philadelphia Expositions. Opening April 24 (Sat), the exhibition focuses on three leading Meiji period Nihon-ga painters who have gained much attention in recent years; Watanabe Seitei, Kawanabe Kyosai and Shibata Zeshin. The exhibition will continue on view through May 5 (Wed), offering roughly 40 works and free admittance. On the Exhibition With the turn of the 19th century came the rise of Euro-American globalization. During this unprecedented period of industrial and cultural prosperity, Centennial Exhibitions became a popular vehicle for countries to showcase their art and tradition. Furthermore, as diverse forms of expression began to be shared across cultures, art flourished and arose with entirely new innovations. Despite the excess, three major Japanese artists took center stage: Watanabe Seitei, Shibata Zeshin and Kawanabe Kyosai. With their originality, elegance and detail, their works caught the attention of the world and transcended the greatest of cultural boundaries. Despite their overwhelming success in the West and the subsequent impact of Japonisme, the exclusion of these artists from mainstream modern Japanese art history Watanabe Seitei, Wisteria allowed for them to be overshadowed for a long time. Thankfully, in recent years, their and Old Willow Tree works have gone re-evaluation and have rightfully regained mass recognition. We welcome you all to take this rare opportunity to collectively witness the works of three esteemed artists, who continue to stun audiences across many generations and cultures. -

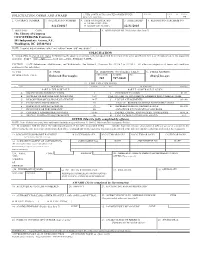

FEDLINK Preservation Basic Services Ordering

SOLICITATION, OFFER AND AWARD 1. THIS CONTRACT IS A RATED ORDER UNDER RATING PAGE OF PAGES DPAS (15 CFR 700) 1 115 2. CONTRACT NUMBER 3. SOLICITATION NUMBER 4. TYPE OF SOLICITATION 5. DATE ISSUED 6. REQUISITION/PURCHASE NO. G SEALED BID (IFB) S-LC04017 G NEGOTIATED (RFP) 12/31/2003 7. ISSUED BY CODE 8. ADDRESS OFFER TO (If other than Item 7) The Library of Congress OCGM/FEDLINK Contracts 101 Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC 20540-9414 NOTE: In sealed bid solicitations “offer” and “offeror” mean “bid” and “bidder” SOLICITATION 9. Sealed offers in original and copies for furnishing the supplies or services in the Schedu.le will be received at the place specified in Item 8, or if handcarried, in the depository located in Item 7 until __2pm______ local time __Tues., February 4, 2004_. CAUTION -- LATE Submissions, Modifications, and Withdrawals: See Section L, Provision No. 52.214-7 or 52.215-1. All offers are subject to all terms and conditions contained in this solicitation. 10. FOR A. NAME B. TELEPHONE (NO COLLECT CALLS) C. E-MAIL ADDRESS INFORMATION CALL: Deborah Burroughs AREA CODE NUMBER EXT. [email protected] 202 707-0460 11. TABLE OF CONTENTS ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) PART I - THE SCHEDULE PART II - CONTRACT CLAUSES A SOLICITATION/CONTRACT FORM 1 I CONTRACT CLAUSES 91-97 B SUPPLIES OR SERVICES AND PRICE/COST 3-23 PART III - LIST OF DOCUMENTS, EXHIBITS AND OTHER ATTACH. C DESCRIPTION/SPECS./WORK STATEMENT 24-77 J LIST OF ATTACHMENTS 98-100 D PACKAGING AND MARKING 78 PART IV - REPRESENTATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS E INSPECTION AND ACCEPTANCE 79 K REPRESENTATIONS, CERTIFICATIONS 101-108 F DELIVERIES OR PERFORMANCE 80 AND OTHER STATEMENTS OF OFFERORS G CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION DATA 81-89 L INSTRS., CONDS., AND NOTICES TO OFFERORS 109-114 H SPECIAL CONTRACT REQUIREMENTS 90 M EVALUATION FACTORS FOR AWARD 115 OFFER (Must be fully completed by offeror) NOTE: Item 12 does not apply if the solicitation includes the provisions at 52.214-16, Minimum Bid Acceptance Period. -

THE MISUMI COLLECTION Important Works of Lacquer Art and Paintings: Part II Tuesday 10 November 2015

THE MISUMI COLLECTION Important Works of Lacquer Art and Paintings: Part II Tuesday 10 November 2015 THE MISUMI COLLECTION Important Works of Lacquer Art and Paintings: Part II Tuesday 10 November 2015 at 1pm 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Please see page 2 for bidder Saturday 7 November 11am - 5pm Specialist, Head of Department Monday to Friday 8.30 to 6.00 information including after-sale Sunday 8 November 11am - 5pm Suzannah Yip +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 collection and shipment Monday 9 November 9am - 7.30pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8368 [email protected] Please see page 4 for bidder For the sole purpose of providing SALE NUMBER: information including after-sale estimates in three currencies in the catalogue the conversion 23268 Cataloguer collection and shipment Yoko Chino has been made at the exchange rate of approx. CATALOGUE: +44 (0) 20 7468 8372 Physical Condition of Lots in [email protected] this Auction £1: ¥185.6985 £25.00 £1: USD1.5400 Department Assistant PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE Please note that this rate may well BIDS Masami Yamada IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS have changed at the date of +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 +44 (0) 20 7468 8217 CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL the auction. +44 (0) 20 7447 4401 fax [email protected] CONDITION OF ANY LOT. To bid via the internet please INTENDING BIDDERS MUST お品物のコンディションについて visit bonhams.com Senior Consultants SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO Neil Davey THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT 本カタログにはお品物の損傷等 Please note that bids should be +44 (0) 20 7468 8288 AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 15 コンディションの記述は記載 submitted no later than 4pm on [email protected] OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS されていないことを、予めご了 the day prior to the sale. -

Urushi-E Is an Urushi-Based Painting. the Term Applies Much the Same Way That the Term “Oil Painting” Describes the Use of Oil-Based Paints

“Independence of Urushi-e” Urushi-e is an Urushi-based painting. The term applies much the same way that the term “oil painting” describes the use of oil-based paints. The reason for declaring the “independence of Urushi-e” arises from the common perception that craft-oriented maki-e, or a sprinkled picture decoration, comes to one’s mind when the term Urushi-e is mentioned. This is simply because there have been hardly any Urushi-e artworks in the past. If examined further, one can find Urushi-e in its pure form among the fine arts, but such artworks have not succeeded in enhancing the advantages of Urushi when compared to inkbrush artworks painted on paper and silk materials. I had sixteen pieces of my Urushi-e artworks exhibited for four days at the Japan Industrial Club, beginning on November 11 (1934). The exhibit was a summation of a decade of my work. It is uncertain whether the exhibit will trigger a sensation in the artistic future in Japan, however, I feel confident about the positive feedback I’ve received. My creative works stand as artworks in an independent field. The following descriptions outline the uniqueness of my work while making comparisons to techniques in other fields of artistic endeavor. It is particularly appropriate that Urushi-e has its origin in Japan. Urushi-e has great potential to grow as a form of fine art, given its rich local characteristics. As widely known, Urushi is a product only seen in Asia, and today Japan still produces the highest-quality Urushi.