The Welsh Fairy Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management Plan 2014 - 2019

Management Plan 2014 - 2019 Part One STRATEGY Introduction 1 AONB Designation 3 Setting the Plan in Context 7 An Ecosystem Approach 13 What makes the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley Special 19 A Vision for the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley AONB 25 Landscape Quality & Character 27 Habitats and Wildlife 31 The Historic Environment 39 Access, Recreation and Tourism 49 Culture and People 55 Introduction The Clwydian Range and Dee lies the glorious Dee Valley Valley Area of Outstanding with historic Llangollen, a Natural Beauty is the dramatic famous market town rich in upland frontier to North cultural and industrial heritage, Wales embracing some of the including the Pontcysyllte country’s most wonderful Aqueduct and Llangollen Canal, countryside. a designated World Heritage Site. The Clwydian Range is an unmistakeable chain of 7KH2DȇV'\NH1DWLRQDO heather clad summits topped Trail traverses this specially by Britain’s most strikingly protected area, one of the least situated hillforts. Beyond the discovered yet most welcoming windswept Horseshoe Pass, and easiest to explore of over Llantysilio Mountain, %ULWDLQȇVȴQHVWODQGVFDSHV About this Plan In 2011 the Clwydian Range AONB and Dee Valley and has been $21%WRZRUNWRJHWKHUWRDFKLHYH was exteneded to include the Dee prepared by the AONB Unit in its aspirations. It will ensure Valley and part of the Vales of close collaboration with key that AONB purposes are being Llangollen. An interim statement partners and stake holders GHOLYHUHGZKLOVWFRQWULEXWLQJWR for this Southern extension including landowners and WKHDLPVDQGREMHFWLYHVRIRWKHU to the AONB was produced custodians of key features. This strategies for the area. in 2012 as an addendum to LVDȴYH\HDUSODQIRUWKHHQWLUH the 2009 Management Plan community of the AONB not just 7KLV0DQDJHPHQW3ODQLVGLHUHQW for the Clwydian Range. -

Aerial Archaeology Research Group - Conference 1996

AERIAL ARCHAEOLOGY RESEARCH GROUP - CONFERENCE 1996 PROGRAMM.E Wednesday 18 September 10.00 Registration 12.30 AGM 13.00 Lunch 114.00 Welcome and Introduction to Conference - Jo EIsworthIM Brown Aerial Archaeology in the Chester Area t'14.10 Archaeology in Cheshire and Merseyside: the view from the ground Adrian Tindall /14.35 The impact of aerial reconnaissance on the archaeology of Cheshire and Merseyside - Rob Philpot . {/15.05 Aerial reconnaissance in Shropshire; Recent results and changing perceptions Mike Watson 15.35 ·~ 5The Isle of Man: recent reconnaissance - Bob Bewley 15.55 Tea News and Views V16.l0 The MARS project - Andrew Fulton 16.4(}1~Introduction to GIS demonstrations 10/17.15 North Oxfordshire: recent results in reconnaissance - Roger Featherstone 17.30 Recent work in Norfolk - Derek Edwards 19.30 Conference Dinner 21 .30 The aerial photography training course, Hungary, June 1996 - Otto Braasch Historical Japan from the air - Martin Gojda Some problems from the Isle ofWight - David Motkin News and Views from Wales - Chris Musson Parchmarks in Essex - David Strachan Thursday 19 September International Session 9.00 From Arcane to Iconic - experience of publishing and exhibiting aerial photographs in New Zealand - Kevin Jones 9.40 The combined method of aerial reconnaissance and sutface collection - Martin Gojda "c j\ 10.00. Recent aerial reconnaissance in Po1and ·"Bf1uL,fi~./ 10.10'1 CtThirsty Apulia' 1994 - BaITi Jones 10.35 The RAPHAEL Programme of the European Union and AARG - Otto Braasch 10.45 Coffee 11.00 TechnicaJ -

A TIME for May/June 2016

EDITOR'S LETTER EST. 1987 A TIME FOR May/June 2016 Publisher Sketty Publications Address exploration 16 Coed Saeson Crescent Sketty Swansea SA2 9DG Phone 01792 299612 49 General Enquiries [email protected] SWANSEA FESTIVAL OF TRANSPORT Advertising John Hughes Conveniently taking place on Father’s Day, Sun 19 June, the Swansea Festival [email protected] of Transport returns for its 23rd year. There’ll be around 500 exhibits in and around Swansea City Centre with motorcycles, vintage, modified and film cars, Editor Holly Hughes buses, trucks and tractors on display! [email protected] Listings Editor & Accounts JODIE PRENGER Susan Hughes BBC’s I’d Do Anything winner, Jodie Prenger, heads to Swansea to perform the role [email protected] of Emma in Tell Me on a Sunday. Kay Smythe chats with the bubbly Jodie to find [email protected] out what the audience can expect from the show and to get some insider info into Design Jodie’s life off stage. Waters Creative www.waters-creative.co.uk SCAMPER HOLIDAYS Print Stephens & George Print Group This is THE ultimate luxury glamping experience. Sleep under the stars in boutique accommodation located on Gower with to-die-for views. JULY/AUGUST 2016 EDITION With the option to stay in everything from tiki cabins to shepherd’s huts, and Listings: Thurs 19 May timber tents to static camper vans, it’ll be an unforgettable experience. View a Digital Edition www.visitswanseabay.com/downloads SPRING BANK HOLIDAY If you’re stuck for ideas of how to spend Spring Bank Holiday, Mon 30 May, then check out our round-up of fun events taking place across the city. -

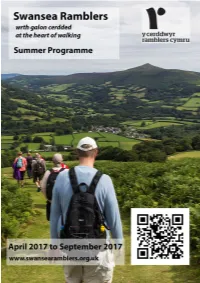

17Th Programme – Swansea Ramblers We Offer Short & Long Walks All Year Around and Welcome New Walkers to Try a Walk with U

17th Programme – Swansea Ramblers We offer short & long walks all year around and welcome new walkers to try a walk with us. 1 Front Cover Photograph: Table Mountain with view of Sugar Loaf v14 2 Swansea Ramblers’ membership benefits & events We have lots of walks and other events during the year so we thought you may like to see at a glance the sort of things you can do as a member of Swansea Ramblers: Programme of walks: We have long, medium & short walks to suit most tastes. The summer programme runs from April to September and the winter programme covers October to March. The programme is emailed & posted to members. Should you require an additional programme, this can be printed by going to our website. Evening walks: These are about 2-3 miles and we normally provide these in the summer. Monday Short walks: We also provide occasional 2-3 mile daytime walks as an introduction to walking, usually on a Monday. Saturday walks: We have a Saturday walk every week that is no more than 6 miles in length and these are a great way to begin exploring the countryside. Occasionally, in addition to the shorter walk, we may also provide a longer walk. Sunday walks: These alternate every other week between longer, harder walking for the more experienced walker and a medium walk which offers the next step up from the Saturday walks. Weekday walks: These take place on different days and can vary in length. Most are published in advance but we also have extra weekday walks at short notice. -

The Thirteenth Mt Haemus Lecture

THE ORDER OF BARDS OVATES & DRUIDS MOUNT HAEMUS LECTURE FOR THE YEAR 2012 The Thirteenth Mt Haemus Lecture Magical Transformation in the Book of Taliesin and the Spoils of Annwn by Kristoffer Hughes Abstract The central theme within the OBOD Bardic grade expresses the transformation mystery present in the tale of Gwion Bach, who by degrees of elemental initiations and assimilation becomes he with the radiant brow – Taliesin. A further body of work exists in the form of Peniarth Manuscript Number 2, designated as ‘The Book of Taliesin’, inter-textual references within this material connects it to a vast body of work including the ‘Hanes Taliesin’ (the story of the birth of Taliesin) and the Four Branches of the Mabinogi which gives credence to the premise that magical transformation permeates the British/Welsh mythological sagas. This paper will focus on elements of magical transformation in the Book of Taliesin’s most famed mystical poem, ‘The Preideu Annwfyn (The Spoils of Annwn), and its pertinence to modern Druidic practise, to bridge the gulf between academia and the visionary, and to demonstrate the storehouse of wisdom accessible within the Taliesin material. Introduction It is the intention of this paper to examine the magical transformation properties present in the Book of Taliesin and the Preideu Annwfn. By the term ‘Magical Transformation’ I refer to the preternatural accounts of change initiated by magical means that are present within the Taliesin material and pertinent to modern practise and the assumption of various states of being. The transformative qualities of the Hanes Taliesin material is familiar to students of the OBOD, but I suggest that further material can be utilised to enhance the spiritual connection of the student to the source material of the OBOD and other Druidic systems. -

The People of Pim

The People of Pim For Dad who remembers when fairies were evil, and for me who tries to believe there is a reason behind it. Once upon on a time there were a blessed and wise people from somewhere Far East who lived on and around a beautiful gigantic Cyress Tree known to them as the Great Yoshino, which means respect. They were a semi-nomadic people, living high up in the tree in summer where the weather was cooler and moving down the great tree in winter to tuck their homes and animals under the warm protection of the big boughs. They were never far from the tree though. Their animals grazed on moss that grew on the boughs, the children hopped and climbed from branch to branch, and they held all celebrations in and under the tree. [Now look waaaay up!] When one climbed higher up the whorled branches, as if climbing up a big spiraling medieval staircase, the boughs became a little more barren, were shorter, and tasty herbs and tiny alpine flowers were hidden in the sweet piney smelling needles high up. This was the beauty and draw of the Great Yoshino tree for them. When anyone of them needed to clear their minds they would just climb high into the tree and simply sit and just be for a little while. The tree was their connection between the earth and the world beyond, the quietness up there gave them their strength and great wisdom. Now this tribe was famous in the region for a rare breed of goat called the Tamar. -

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

Ro B Collister

Created in 1951, the Snowdonia National Park is a landscape of rugged grandeur, great natural diversity and cultural associations going back thousands of years. The vision of its founders was that this very special region should be protected from harmful development for all time. From the beginning, how- ever, there were problems ... Out of these difficulties R OB C OLLISTE R grew the idea of an independent society dedicated to conserving and enhancing the landscape. Today Rob Collister is an international mountain guide who the Snowdonia Society has a membership of 2,500 lives in the Conwy Valley. He has been a member and enjoys a close working relationship with both the of the Snowdonia Society for thirty years and was Snowdonia National Park Authority and the Council a Nominated Member of the Snowdonia National for National Parks. Park Committee from 1990 –1993. He is the author of Lightweight Expeditions (1989) and Over the Hills This lively narrative chronicles the story of the and Far Away (1996). Snowdonia Society – its successes and failures, its internal conflict and the personalities involved – as Mae Rob Collister yn arweinydd mynydd rhyngwladol well as discussing the wider issues which have af- sy’n byw yn Nyffryn Conwy. Mae wedi bod yn aelod fected this unique landscape over the last forty years. o Gymdeithas Eryri ers deng mlynedd ar hugain, a’n Aelod Enwebedig o Bwyllgor Parc Cenedlaethol Eryri o 1990 -1993. Ef yw awdur Lightweight Expeditions Crëwyd Parc Cenedlaethol Eryri ym 1951. Mae’r (1989) ac Over the Hills and Far Away (1996). tirwedd yn hagr ac yn hardd, yn llawn amrywiaeth naturiol gogoneddus ac mae yma gysylltiadau diwyl- liannol ers miloedd o flynyddoedd. -

Celtic Folklore Welsh and Manx

CELTIC FOLKLORE WELSH AND MANX BY JOHN RHYS, M.A., D.LITT. HON. LL.D. OF THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH PROFESSOR OF CELTIC PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, OXFORD VOLUME II OXFORD CLARENDON PRESS 1901 Page 1 Chapter VII TRIUMPHS OF THE WATER-WORLD Une des légendes les plus répandues en Bretagne est celle d’une prétendue ville d’ls, qui, à une époque inconnue, aurait été engloutie par la mer. On montre, à divers endroits de la côte, l’emplacement de cette cité fabuleuse, et les pecheurs vous en font d’étranges récits. Les jours de tempéte, assurent-ils, on voit, dans les creux des vagues, le sommet des fléches de ses églises; les jours de calme, on entend monter de l’abime Ie son de ses cloches, modulant l’hymne du jour.—RENAN. MORE than once in the last chapter was the subject of submersions and cataclysms brought before the reader, and it may be convenient to enumerate here the most remarkable cases, and to add one or two to their number, as well as to dwell at some- what greater length on some instances which may be said to have found their way into Welsh literature. He has already been told of the outburst of the Glasfryn Lake and Ffynnon Gywer, of Llyn Llech Owen and the Crymlyn, also of the drowning of Cantre’r Gwaelod; not to mention that one of my informants had something to say of the sub- mergence of Caer Arianrhod, a rock now visible only at low water between Celynnog Fawr and Dinas Dintte, on the coast of Arfon. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

A Study of the Diets of Feral Goat Populations in the Snowdonia National Park

A Study of the diets of Feral Goat Populations in The Snowdonia National Park. Bryan Glenville Dickinson BSc HONS (Wales) A thesis submitted in candidature for the Degree of Magister in Philosphiae in the University of Wales. School of Agriculture and Forest Sciences University of North Wales February 1994 SUMMARY A study of the botanical composition of feral goat (Capra hircus) diets was carried out using faecal analysis. Two groups of goats in the northern part of the Snowdonia National Park were selected, one using mainly lowland deciduous woodland, the other restricted to upland heath at over 400 m altitude. Diets of male and female goats were analysed separately on a monthly basis and related to information on range, group structure and habitat utilisation. At the upland site little segregation of the sexes took place and overall diets between the sexes were similar. Thirty plant species were identified in the faeces, and the overall diet consisted of approximately 50 % monocotyledonous plants (mainly grasses and sedges), 40 % ericaceous shrubs, and 10 % ferns, herbs and bryophytes. Dwarf shrubs were important throughout the year. Grasses, especially Nardus stricta, were consumed in late winter and spring but were replaced by sedges in late spring and early summer. At the lowland site the group was much larger, and a greater degree of dispersal and sexual segregation occurred. Over fifty plant species were identified and overall faecal composition differed between the sexes. Male diet consisted of approximately 15 % monocotyledonous species (mainly grasses), 67 % tree browse (leaves) and dwarf shrubs, 10 % ferns and 8 % herbs and bryophytes. -

Black Dogs Represent Evil, Having Derived from Odin’S Black Hound in Viking Mythology’

Cave Canem by Chris Huff The Black Dog phenomenon remains an enduring connection to our ancient history. But many of the ‘facts’ we thought we knew about the phenomenon may not be true after all. Black Dog (henceforth BD) legends and folk tales are known from most counties of England, there are a few from Wales and one example that is known to the author, from the Isle of Man. There are many tales about these spectral animals. Few are alleged, in the popular sources, to bode well for the witness, and there has grown a misleading folklore around the phenomenon which is largely unsubstantiated by the scanty evidence. What exists is a collection of folk tales, spread across the length and breadth of Britain, about large spectral hounds, with black fur, large glowing eyes and perhaps an ethereal glow around them, which may explode, emit sulphurous breath, augur death and misfortune and produce poltergeist-like activity. At the outset I must take pains to point out that any recorded examples of BDs which may be a genuine haunting by a dog which happened to be black have (bar one at Ivelet in Swaledale) been screened out. The evidence presented below is not comprehensive but is believed to be a representative sample of the available recorded cases and thus may produce an insight into the phenomenon, or promote further in-depth study. Some common misconceptions or misrepresentations about the BDs include the following three statements: (1) It has frequently been claimed that the BDs are to be found in the Anglo-Saxon and Viking areas of Britain.